Waleed F. Mahdi

POST-ORIENTAL OTHERNESS: HOLLYWOOD’S MORAL GEOGRAPHY OF ARAB AMERICANS

Abstract

How do filmmakers in the United States play a role in perpetuating narratives of belonging to the American culture? What is the making line between Orientalist and post-Orientalist articulations of Arabness? In what ways have the transnational configurations of geopolitics affected the image formations of Arab Americans in Hollywood? This article emerges at the intersection of those inquiries and provides a historical account of Hollywood’s representation of Arab Americans rooted in the 1970s. This decade, I argue, constitutes a turning point in the industry’s nationalist projections of Arabness from an Orientalist trope for Arabia to a post-Orientalist notion influenced by US–Arab and Arab–Israeli geopolitics. It replaces an earlier moral geography that consumes the Orient while remaining distant from it with a new moral geography that constantly questions Arab Americans’ belonging through narratives of alienness and terrorism. The significance of this work lies in its investigation of the historical trajectory of Hollywood’s engagement with Arab American cultural identity.

INTRODUCTION

It seems barely an exaggeration to say that Arab and Muslim Americans are constantly talked about but almost never heard from. The problem is not that they lack representations but that they have too many. And these are all abstractions. Arabs and Muslims have become a foreign-policy issue, an argument on the domestic agenda, a law-enforcement priority, and a point of well-meaning concern. They appear as shadowy characters on terror television shows, have become objects of sociological inquiry, and get paraded around as puppets for public diplomacy . . . They are floating everywhere in the virtual landscape of the national imagination, as either villains of Islam or victims of Arab culture.

— Moustafa Bayoumi, How Does it Feel to be a Problem1

Popular culture in the United States functions through sensational and rating-based entertainment. It also promotes a hegemonic frame of reference for cultural citizenship and national belonging in the life of “cultural citizens.”2 It serves as an ideological state apparatus, to echo French philosopher Louis Althusser, guiding citizens through an acculturation process that homogenizes their own subjectivity.3 In this sense, this article defines cultural citizenship as a tool to subjectify minorities through the mediation of popular culture.4 In his scholarly reviews of Hollywood’s history, Lary May emphasizes the cinema’s role in enunciating cultural citizenship. Hollywood, he argues, has been a site of fury for debates around “good citizenship” because of its connection to “political power, cultural authority, and the very meaning of national identity.”5 For decades, Hollywood has played a major role in circulating a popular sense of American collective imagination and manufacturing sensational conceptions of cultural Otherness. Numerous scholars have offered valid critiques of the cinema’s alienation of Natives, Latinos, Asians, communists, Jews, and African Americans from US mainstream cultural scene.6

Hollywood’s conflated articulation of Arabness and Islam operates on the similar premise of diminishing cultural difference through the Manichean paradigm of binary opposition; for example, good versus evil, civilized versus backward, peaceful versus violent, and so on. Jack Shaheen has investigated this reductive binary code, and criticized its repertoire of Arab stereotypes and images.7 This article delves into Hollywood’s history and examines its role in defining the cultural citizenship of the Arab American community. Towards that end, it offers a historical overview of Hollywood’s representation patterns of Arab Americans rooted in the 1970s. This decade, I argue, constitutes a critical turning point in the industry’s projections of Arabness away from an Orientalist trope for Arabia towards a post-Orientalist notion influenced by US–Arab and Arab–Israeli geopolitics. By post-Orientalism, I build on Melani McAlister’s reading of post-WWII changes in US–Arab encounters by emphasizing the intricate interplay of US cultural productions and sociopolitical changes during the 1970s, which cannot be read through Edward Said’s influential Orientalist framework.8 The boundaries of this interplay draw from echoes of US foreign policy; roles of Israeli diasporic filmmakers in mediating their version of the Arab–Israeli conflict to American audiences; and anxieties around the increasing presence of Arab and Muslim immigrants with a deep commitment to activism and agency.

The 1970s departed from an earlier audience-targeted filmmaking emphasis on consuming the Orient while remaining distant from it. It embraced different sensational images of Arabs and Arab Americans through narratives of alienness and terrorism. This transition was rooted in two primary patterns of representation. The first pattern refurbished early images of Arabia and imparted new constructions dictated by the 1970s energy crisis. The second pattern borrowed Israeli productions of “Arabs as terrorists” and defined Arab Americans through Hollywood’s codes of American cultural citizenship. The framework of this article is designed to capture the metanarratives of those patterns; hence, it is beyond the scope of this work to offer comprehensive textual analysis of each highlighted film. The significance of this method lies in its investigation of the historical trajectory of Hollywood’s engagement with the cultural identity of Arab American community. It delineates the Arab American image in US popular culture without dismissing the importance of 9/11 in espousing an exclusionary nationalist fervor, which continues to resurrect a deeply rooted stigma against Arabs, Muslims, and look-a-likes in American cultural memory.

ARAB AMERICANS: A NEW MORAL GEOGRAPHY

Hollywood’s projection of the Arab image has contributed more than 1,300 films, the majority of which entertain superficial and denigrating images of Arabs and Muslims while promoting representation patterns that articulate Arabness in explicitly nationalist terms. Its productions, particularly during the silent era, featured fetishized and exotic images of Arabs and registered the potency of the Orientalist discourse in American culture, contributing to what Abdelmajid Hajji identifies as “the Oriental Genre.”9 The element of Arab foreignness in early films like The Arab (1915), The Garden of Allah (1916), Intolerance (1916), Cleopatra (1917), Salome (1918), An Arabian Knight (1920), The Sheik (1921), A Son of the Sahara (1924), Son of the Sheik (1926), and A Son of the Desert (1928) created a buffer zone or, as McAlister puts it, a moral geography for Americans to both experience pleasures of the Orient—romance, exotic milieus, and harem sexual allure—while spatially and culturally distancing themselves from it.10 In an era defined by mass consumption, the sheer volume of films produced—at least eighty-seven films during the 1920s—demonstrated Hollywood’s power in mediating this moral geography.11 Most of the films produced prior to the rise of the United States as a post-World War II super power and its adoption of an interventionist foreign policy in the Middle East circulated this Orientalist framework. Arabs were depicted as primitive people living in tents in between sand dunes, or in underdeveloped cities full of dirt and chaos. Backwardness and violence were their innate characteristics. Arab women were often perceived as submissive, covered from top to toe, with no choice but to abide by certain patriarchal rules. At other times, they were viewed within the lenses of sensuality; they were either belly dancing seductively with their semi-naked bodies, or bathing in harems.12

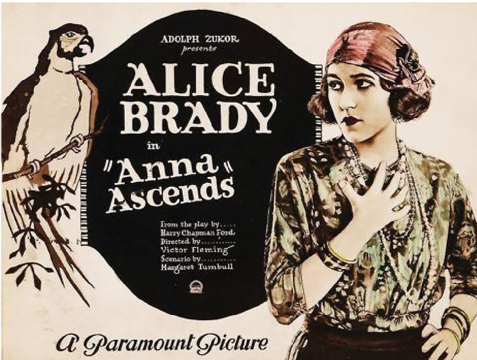

The earliest traceable film featuring Arab Americans prior to the 1970s is Victor Fleming’s Anna Ascends (1922) (Figure 1).13 An adaptation of Henry Chapman Ford’s play bearing the same title, the film fetishizes the correlation between acculturation and upward mobility in the life of a Syrian American waitress, Anna Ayyob (Alice Brady). The film’s assimilation narrative is reflective of the priorities of the first wave of Arab immigrants (1880–1920). According to oral historian Alixa Naff, this wave—mostly based on the influx of Arab Christians from Ottoman ruled Great Syria (modern-day Syria and Lebanon)—was composed of hardworking peddlers with a deep commitment to family and religion.14 Dow v. United States (1915) signified a moment of triumph for these individuals in claiming their whiteness, which constituted a racial resolution to naturalization-based citizenship at the time.15 Parallel to the legal battle, Arab Americans struggled to negotiate for sociocultural inclusion, and exhibited efforts to integrate and assimilate into the larger culture. The failure of filmmakers to capture the nuance of this particular history was partly informed by the Orientalist representation mode of the time, a byproduct of a cultural trend in consuming the distant Orient. “The dearth of American silent films reflecting the Arab immigrants’ experience” argues Hajji, “is largely due to the fact that the Arab in these films is mostly a concept, a trope, a fabrication of the imagination of Westerners.”16

Other factors accounting for the industry’s lack of interest in Arab immigrant’s narrative could be attributed to the intertwinement of US encounters with the Middle East and the restrictive national-origin quota system of Johnson-Reed Act (1924–1965). America’s investment in the region’s geopolitics did not fully unfold until the aftermath of World War II, translating into a more sensational deployment of national politics, particularly regarding Israel. Meanwhile, the Johnson-Reed Act’s annual cap of 523 Arab emigres significantly controlled the Arab presence in the United States. The Arab migration was regulated as follows: Arabian Peninsula (100), Egypt (100), Iraq (Mesopotamia) (100), Palestine (with Trans-Jordan) (British mandate) (100), and Syria and the Lebanon (French mandate) (123).17 The second wave of Arab immigrants during the period 1940s–1960s did not gain recognition in the film industry, which was still dominated by early Orientalist imaginations of Arabia.18

The liberalization of US immigration law through Hart-Celler Act (1965), however, facilitated the arrival of the third wave of Arab immigrants leading to a current estimate of 3.5 million Arab Americans, more diverse in terms of religion and nationality.19 The correlation of US neocolonial interference in the Arab and Muslim worlds since the 1950s and the active engagement of the third wave in US–Arab as well as Arab–Israeli politics of activism forged a space for Hollywood to devote some of its films to mainstream sensational imagery of the Arab presence in the United States in terms of foreign policy and national security. Examples of this trend include films like The Next Man (1976), Black Sunday (1977), Wrong is Right (1982), Wanted: Dead or Alive (1987), Terror in Beverly Hills (1988), Navy Seals (1990), True Lies (1994), The Siege (1998), Pretty Persuasion (2004), Fatwa (2006), Traitor (2008), and The Unthinkable (2010).

In this context, the industry’s denial of Arab American’s right to define their sense of belonging beyond its drawn nationalist boundaries of cultural citizenship offers a sociopolitical statement of hegemony and homogeny. The solidification of this denial since the 1970s, I argue, defines Arab Americans as the interlocutors of a new moral geography in Hollywood that reflects a postOrientalist moment of anxiety informed by US–Arab and Arab–Israeli politics. This moral geography serves as a critical site of transition in the US cultural industry from a passive reproduction of Orientalist imagery into a post-Orientalist active consumption of unfolding geo- and socio-politics. In addition to its temporal reading of the transition, this article emphasizes a spatial transition in the cinematic engagement with Arabness from a symbol of a distant Orient into a signifier of domestic anxiety; a transition that would chart the Arab American image for decades to come. Unpacking this moral geography requires a macro reading of two patterns of representation initiated during the 1970s and informed by both foreign policy and national security concerns.

ARAB AMERICANS AS A FOREIGN POLICY ISSUE

The rivalry between the US and the USSR during the initial stages of the Cold War polarized and divided Arabs. Historian Rashid Khalidi draws a picture of the polarity:

The pressure to join American-sponsored alliance systems. . . played a large role in the polarization in the Arab world that. . . developed into what Malcolm Kerr called the “Arab Cold War,” between a camp headed by Nasser’s Egypt and another headed by King Faisal and Saudi Arabia.20

The Egyptian–Saudi conflict, particularly during the 1960s, spelled out through their support of local conflicts and a global allegiance to socialism and capitalism respectively.21 However, a sense of common Arab grievance against the Israeli occupation of 1948—aka Nakba Day—overshadowed the heated politics of the time.22 The grievance was further solidified in the aftermath of the Arab–Israeli war (1967)—aka Naksa Day—which resulted in the defeat of Egyptian–Syrian–Jordanian military alliance and Israeli seizure of more territories including the West Bank, East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Golan Heights.23 The Arab popular support for Egyptian and Syrian use of force to regain parts of the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights during the October War (1973) was accompanied by oil embargo by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), which cut oil production and restricted petroleum exports to the United States.24

The embargo epitomized Arabs’ response to the US political investment in promoting Israeli interests as a major Cold War ally in the Middle East; an orientation in US foreign policy that John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt trace back to President Kennedy’s administration.25 More importantly, the embargo created an energy crisis in the United States with immediate repercussions in the American street, ranging from fuel shortages to skyrocketing prices and sensational media coverages.26 This socioeconomic context provided Hollywood with a rich source of images illustrating the American cultural conflation of Arabs as money-oriented, oil-rich and extravagant people whose wealth represented the threat of rebranding, if not disrupting, American values of liberty and democracy.

A film like Richard Sarafian’s The Next Man (1976)—aka Arab Conspiracy—showcased this binary by dramatizing Arabs’ rejection of the fictional pro-peace, Israeli-friendly Saudi Arabian minister of state, Khalil Abdulmuhsen (Sean Connery). “I decided to take this role because it’s an unusual one,” Connery stated, “I play an Arab statesman who tries to bring peace to the Mideast by some startling proposals. It’s an intelligent film about what’s happening now, and it has plenty of excitement.”27 Abdulmuhsen is a likeable and well-groomed character with an articulate and proper accent, a visual mark of distinction from Hollywood’s reel Arabs of the time.28 The appeal of the Americanized Arab minister draws from his subscription to a US fantasized approach to resolving the Arab–Israeli conflict. He addresses the United Nations with a proposal for a “new global, social, [and] political contract” that grants Israel admission into OPEC as a non-producing member. He is forceful in pursuing the resolution:

Saudi Arabia is determined to back Israeli acceptance with all the power at its command . . . To those who would work with us towards peace, we embrace you. To those who would keep Arabs and Israelis enemies, we defy you. To those who would keep us apart, we shall overcome you.29

Polarizing reactions to the proposal in the film into us-versus-them binaries projects the dissenting voices of Kuwaiti, Syrian, Iraqi, Libyan, and Egyptian delegates as well as Arab American protestors outside the UN compound as uncompromising and violent. Representations of voices rejecting Abdulmuhsen’s agenda define Arabs and Arab Americans as irrational, impulsive, and anti-western. Protesting banners such as “Arabia for the Arabians” and “No Deals, Khalil” initially channel their anger, which culminates in bombing the protest scene and assassinating the minister.

Prior to his assassination, Abdulmuhsen experiences a direct encounter with the Arab rejection of his peaceful efforts. An angry rally in which Arab Americans express their sentiment against his agenda, which they see undercutting the Palestinian rights, leads protesters to block his car. Having seen a passionate Arab American protester yelling out his opposition, Abdulmuhsen steps out of his car and convinces the police officer to stop arresting him. He reaches out to the unnamed protestor. He acknowledges his concerns about Israeli aggressions and hugs him as a token of recognition for Palestinian rights. He also affirms that peaceful resolution requires time and demands that the protestor trust him. This particular encounter does not necessarily address the protester’s concern as much as it instructs the audiences to identify with the Saudi minister and believe in his resolution to broker an Arab–Israeli peace the American way. In a subsequent scene, the camera captures shady protestors passing bombs, signaling that violence is an Arab measure to silence the minister’s calls for peace.

The most iconic illustration of such US–Arab polarity during the 1970s was communicated by Sidney Lumet’s highly acclaimed satirical film The Network (1976).30 The film is iconic for its critique of the US television as a manipulative tool responsible for producing a generation that “cannot think, cannot feel, and which has learned everything it knows about life from Saturday morning cartoons.”31 Howard Beale (Peter Finch), the anchor of a UPS television network, engenders a critique of Arabs who are planning to buy the channel by inciting the public’s sense of patriotism. Beale takes advantage of his media podium to educate his followers how the Arabs’ presumed monopoly of neoliberal politics seeks to transform the American culture (Figure 2). In an iconic moment of active citizen empowerment in US popular culture, Beale instructs each one of his viewers to get up out of his or her couch and yell out of window, “I am mad as hell and I’m not gonna take this anymore.”32

Beale’s call for public performance resonates with a mythic fear of Arabness. Meant in the Barthesian sense of mythology, a myth solidifies not because of its relevance to “truth” but rather its circulation without critical contestation.33 Fear of Arabs’ oil wealth during the 1970s was partially shaped by Americans’ frustration with the economic challenges of the energy crisis—informed by the aforementioned OAPEC disruptive acts of boycott and OPEC’s frequent price-hikes of oil at the time. In this context, Beale’s built anger represented a moment of anxiety in Hollywood that advocated the portrayal of Arab Americans as a foreign policy issue. The Network made this representation strategy possible through Beale’s passionate televised speech, filled with warnings about a looming danger that far outweighed the grim reality of the economy; specifically, the danger of Arabs “buying up America”:

We all know that the Arabs control 16 billion dollars in this country. They own a chunk of Fifth Avenue, twenty downtown pieces of Boston, a part of the port of New Orleans, [and] an industrial park in Salt Lake City. They own big chunks of the Atlanta Hilton, the Arizona Land and Cattle Company, the Security National Bank in California. They control ARAMCO, so that puts them in EXXON, Texaco, and Mobil Oil. They’re all over: New Jersey, Louisville, and St. Louis, Missouri. And that’s only what we know about them; there’s a hell of a lot more we don’t know about because all of those Arab petrodollars are washed through Switzerland and Canada and the biggest banks in the country. . .

Right now the Arabs have screwed us out of enough American dollars to come right back and with our own money buy General Motors, IBM, IT&T, AT&T, DuPont, US Steel, and twenty other companies. Hell! They already own half of England! So, listen to me, the Arabs are simply buying us.

Beale’s fanfare is similar to that of the 2016 Republication presidential candidate Donald Trump’s. Both Beale and Trump attract rating-based media attention for their uncompromising personalities. They utilize explosive rhetoric as a tool to mislead their audiences. They incite fear of Arabs and Muslims as the embodiment of an alien, if not contradictory, culture to America. They even advocate an aggressive public rejection of Arab and Muslim presence in the United States. Dubbed the “mad prophet of the airwaves,” Beale asks his captivated audience to flood the White House with a million telegrams stating, “I don’t want banks selling my country to the Arabs.” Meanwhile, Trump’s campaign vision promises denying Muslims entry to the United States.34 Unlike the public critical response of Trump’s proposal, Beale’s supporters sent six million telegrams and forced Arabs away from the UPS channel. “The people spoke,” Beale addressed his audience, “The people won. It was a radiant eruption of democracy.”

In his reading of the relationship between Beale and his audience, Craig Hight applauds the film’s ability to challenge the viewers to associate themselves with the television audience depicted in the film.35 This possibility, I stress, is in conversation with the film’s provocative manipulation of Americans’ fears of and discrimination against Arabs, which echoed similar institutional anxieties during the 1970s. In the sting operation dubbed Operation Abscam (1978), for instance, the FBI interrogated thirty politicians—including seven congressional representatives—on suspicion of soliciting support from a staged Arab company named “Abscam,” standing for “Arab scam” or “Abdul scam.” In pursuit of the politicians, FBI agents dressed like rich Arabs and videotaped them accepting bribes. David Russell’s 2013 film American Hustle dramatized this operation, resurrecting a similar caricatured image of the Arab threat. This operation unveiled an institutional attempt to “create the impression that Arabs are a threat to American politics.”36 The same institutional anxiety seemed to prompt the Department of Energy at the time to issue such bumper stickers as “The Faster You Drive, The Richer They Get,” and “Driving 75 is Sheikh; Driving 55 Is Chic.”37

Images of Arabs as a foreign source of corruption in American politics, society, and culture remained prevalent in Hollywood production throughout the 1980s. In Herbert Ross’s Protocol (1984), an Arab emir agrees to allow the United States establish a military base in his unnamed strategic country only in return for marrying a waitress-turned-celebrity Sunny (Goldie Hawn), who saves him from an assassination attempt during his stay in the United States. In the film, the US State Department convinces Sunny to travel to the Middle East as a diplomat. Upon her arrival, she is rather welcomed as a queen. She is shocked to learn about the government’s pre-arrangement with the emir to accommodate his search for a spouse. At the end, Sunny turns into a metaphoric embodiment of America’s purity and innocence while the State Department officers symbolize politicians, corrupted by such emirs who scheme to dictate US foreign policy. In addition to an Arab American protest march about Protocol, the ADC executive director communicated a timely concern to its filmmakers before its release, “We do not suggest that Arabs should not be used nor that they cannot be funny, only that you do not perpetuate the negative and hurtful images employed in depicting our community.”38 Despite promises from the film producer to portray the emir as “a true hero,” the final cut of Protocol presented the emir as a mere embodiment of Americans’ conception of Arabness at the time.39

The trauma of the 1970s oil crisis solidified a popular culture reference to a collective memory of Arabs as foreign disruptors of US national politics. Protocol makes effective use of this reference, especially when rendering Sunny’s vulnerability as symbolic of Americans’ susceptibility to Arabs’ presumed evil plans. In 1986, director Lumet sustained a similar reference to Arabs as oil-rich conspirators whose money was presumed to undercut America’s prosperity in Power (1986). The film’s Arabs—codified in an oil company named Ameriabia—hire a public relations expert, Arnold Billing (Denzel Washington), to support the election of a politician committed to the US retrogress in solar energy. The plot unravels to unveil a conflict over the US fight for independence from oil as its primary source of energy. It deploys Arabness in the form of both shady and shadowy characters with an agenda to control US politics. The rejection of Arabs’ interference, therefore, becomes a metaphoric expression of an American rescue narrative. Such a reductive narration style demonstrates how the oil crisis factor contributed to paranoia about Arab nations during the 1970s and beyond.

This trend of representation best served as a transition from Hollywood’s earlier depiction pattern of Arabs as desert-dwelling, camelriding sheikhs to a post-1970s pattern of Arabs-in-America as superficially material-seeking to corrupt American life. It often generated derisive humor based on exaggerated polarity between the American and the Arabic cultural identities. The Arab American characters in this pattern were imagined as incapable of conversing with American codes and values. Films like The Happy Hooker Goes to Washington (1977), Cheech and Chang’s Next Movie (1980), Underground Aces (1980), The Cannonball Run (1981), Things Are Tough All Over (1982), Rollover (1982), The Cannonball Run 2 (1984), St. Elmo’s Fire (1985), Father of the Bride Part II (1995), Kazaam (1996), Simpatico (1999), Two Degrees (2001), Dreamer: Inspired by a True Story (2005), and Click (2006) all feature polarized caricatured images of Arab Americans, and dissociate them from any affiliation with the American culture.

Reel Arab Americans in these movies operate at the periphery of the American society and only exist to solidify a process of Otherness that denies real Arab Americans their right of belonging to the US. Their foreignness is encoded through certain elements: Orientalist-inspired dress code often mixed with western clothing for comedic relief; impulsive rush to anger; fantasy about romancing blonde-haired women and camels; and commitment to subjugating Americans to their whims.40 Thus, the depiction of Arab Americans in such films as the antithesis of US codes, values, and even politics enabled Hollywood writers, actors, and directors to construct a new wave of imagery that portrayed Arab Americans as anonymous individuals, often cartoonish, if not evil. Their foreignness constituted the primary ingredient of their un-Americanness. This pattern of depiction emerged as a nationalist response to make sense of the transnational impact of the oil crisis on Americans’ cultural memory. It is through such a national trauma that Americans interacted with and produced concepts of their nation and fellow citizens.41

ARAB AMERICANS AS A NATIONAL SECURITY THREAT

Parallel to Hollywood’s engagement with Arab Americans as a foreign policy issue in the 1970s was another portrayal mode, which imagined them as alien terrorists fixated on undermining the United States’ national security. Hollywood’s constructions of foreign terrorism-related plots were historically rooted in World War II films—one of the earliest examples was Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942).42 However, the industry’s engagement with Middle Eastern terrorism emerged in the 1970s. This was particularly the result of the 1972 Munich massacre, or Black September.43 In this incident, a self-declared Palestinian resistance group killed two Israeli athletes and hijacked nine during the Olympic Games in Munich (West Germany then). This marked the beginning of an era of an Israeli embattlement with transnational forms of radical resistance mediated to Americans as a front of terrorism fighting.

Prior to the rise of this trend, Hollywood had already circulated proIsraeli films like Judith (1966), Cast of a Giant Shadow (1966), Survival (1968), and Journey to Jerusalem (1968), which presented a glorified image of Israelis.44 By the 1967 Arab–Israeli war, US filmmakers became more engaged in a mode of production marked by the politicization of lsrael as a self-declared western state with a unique US alliance.45 In “The Arab Portrayed,” Said examines the US popular sentiment at the time:

During and after the June war [1967] few things could have been more depressing than the way in which the Arabs were portrayed. Press pictures of the Arabs were almost always of large numbers of people, mobs of hysterical, anonymous men, whereas photographs of the Israelis were almost always of stalwart individuals, the light of simple heroism shining from their eyes. . . What is extremely important here is how the official Israeli view of the Arab as a kind of troublesome none person feeds the common and accepted view of the Arab that is currently held in America.46

Portrayals of Arab danger in the media mobilized the rise of a generation of Arab American activists deeply invested in the Arab–Israeli conflict and US–Arab cultural encounters. The label “Arab American” itself was embraced as a post-1967 tool of political activism, which replaced an earlier emphasis on ethno-religious enclaves among Arab immigrants with a transcendental pan-Arabist narrative.47 The Organization of Arab Students (OAS)—founded in 1952—increased its profile of campus activism across the US immediately after 1967.48 The American-Arab University Graduates (AAUG) was founded the same year. The two organizations promoted a critique of US–Israeli relations in light of a growing solidarity with the civil rights movement in addition to certain transnational advocacy groups.49 They also publicized their concern about the politicized portrayals of Arabs in the service of enhancing Israeli public image. Other organizations like National Association of Arab Americans (NAAA), American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC), and Arab American Institute (AAI) joined later in their protest of the cultural vilification of Arabs and Arab Americans as anti-western and alien terrorists.50

Black Sunday (1977), produced and released by Paramount Pictures, was the earliest example of Hollywood’s interest in capitalizing on the post-1967 Arab–Israeli polarization. The film presents Arab woman, Dalia Iyad (Marthe Keller), who personifies a foreign threat of an “Arab-German extraction”—US intelligence agents characterize her. The terrorism threat targets 80,000 Americans, including the US president, attending the Super Bowl in Miami. The Arab presence in the United States, the film suggests, invokes a certainty of civilian massacres in the name of political grievances against the United States for its support of Israel. The film’s theatrical trailer invites the American audience to watch the film by inciting fear of the Arab terrorists, who carry the potential to strike the American public with violence in the near future. “Black Sunday,” the narrator’s voice affirms, “It could be tomorrow!” Unlike Steven Spielberg’s contextualized portrayal of Black September in Munich (2005), John Frankenheimer’s Black Sunday sends a primary message to the spectators that the United States and Israel are aligned in their war against Arabs’ “acts of terror.” Throughout the film, Mossad agent David Kabakov (Robert Shaw) and FBI agent Sam Corley (Fritz Weaver) succeed in tracking the terrorists affiliated with a Black September movement, and emerge as saviors of US security and order. Aligning Israel and the United States as a front against Arab terrorism in this film set the precedence for this pattern of representations, which reached its climax in subsequent decades.

Mediating pro-Israeli and anti-Arab images through the context of terrorism was made possible, to some extent, by Israeli diasporic film productions in the United States. In 1979, Israeli cousins Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus purchased Cannon Films, and produced thirty low-and medium budget works created to alienate Arabs and Muslims from the American public.51 In the words of filmmaker Andrew Stewart, Cannon produced “some of the most blatantly racist and sexist exploitation films of the period.”52 The Delta Force (1986), a Golan-Globus Production distributed by Cannon Films, is an example of such films. In his attempt to reenact the 1985 Athens–Beirut TWA hijacking incident, director Golan offers an emotional portrait that equates Arabs with Nazi Germany. The film shows the airplane hijackers blindly committed to singling Jewish passengers for prosecution (Figure 3). Rather than capturing the real negotiation process—which historically led to the release of hostages—the film’s hostages are rescued by the Delta Force in an Israeli token for the necessity of a military response to Arab terrorism.53 The film also imagines the Arab presence in the United States as a source of instability and violence. One of the terrorists, the audiences learn, plans to blow up the White House with help from Arab Americans.

In her critique of the Israeli filmmaking industry, Ella Shohat offers a penetrating reading of the Israeli nationalist narrative, which, she argues, entangles with Eurocentric Orientalist geographies of East and West in its engagement with the image of Arabs and Arab Jews.54 As products of a diasporic Israeli cinema, the Golan-Globus films highlighted this narrative by foregrounding American vulnerability (as a proxy for Israel), and advocating war as the ultimate response. Films like The Ambassador (1984), Hell Squad (1985), Invasion USA (1985), Appointment with Death (1988), The Hitman (1991), The Delta Force 3: The Killing Games (1991), American Ninja 4: The Annihilation (1991), American Samurai (1992), The Human Shield (1992), and Chain of Command (1993) staged an Israeli imagination of Arabs as permanent enemies of the United States. Other films like Firewalker (1986), Surrender (1987), Allan Quatermain and the Lost City of Gold (1987), Bloodsport (1988), and American Ninja 3: Blood Hunt (1989) injected stereotypical images and slurs in plots not related to Arabs or Muslims. The process of vilification continued beyond the Golan-Globus corpus, sustained by other Israeli producers in such films as Deadly Heroes (1994), Delta Force One (1999), Operation Delta Force V (1999), and The Order (2001). Perhaps Air Marshal (2003)—produced by Avi Lerner, Boaz Davidson, and Alain Jakubowicz—is one of such offensive Israeli portrayals of the Arab and Muslim threat. The low-budget film narrates the story of a US air marshal, Brett Prescott (Dean Cochran), who saves the day along with a cast of Israeli actors by eliminating the Muslim airplane hijacker. This airplane disaster movie, in the words of a reviewer, is “completely shameless in its depiction of an airplane hostage situation in the post-9/11 world.”55 It subscribes to an Israeli commitment to market fear and racism for American consumption.

Terrorism-related plots in the above-highlighted films were “not accidental, but propaganda disguised as entertainment.”56 They reflected the manifestations of lsraeli diasporic articulation of Arabness, which transcended the silver screen. The rising atrocities against Arab Americans during the 1980s were fueled by a rising sense of anti-Arab racism in the United States. The assassination of the west coast regional director of the ADC, Alex Odeh, on 11 October 1985 stands as an iconic reference to violence committed against the Arab American community at the time. Nabeel Abraham accounts for three main sources of anti-Arab sentiment during that period: xenophobic nativism, jingoistic racism, and ideologically motivated violence. While the first two sources were byproducts of “hyper ethnocentrism” in the US racialized discourse, the last one invoked the aforementioned alignment between Israel and the United States. The Jewish Defense League (JDL) and other Jewish extremist groups aggressively enforced this alignment as part of a widened Arab–Israeli conflict. Their actions were ideologically motivated and “premeditated,” Abraham confirms, “not merely spontaneous outbursts stemming from anger, fear, or ignorance.”57

Israeli portrayals contributed to the development of an American filmmaking code of Arab Americans. The cinema’s one-dimensional imagination of Arab threat was certainly exacerbated by such loaded incidents as the Iran hostage crisis (1979–1981), intervention in Lebanon (1981–1983), the Iran–Iraq war (1980–1988), bombing of Libya (1986), and the World Trade Center bombing (1993). Hollywood’s trendy association of Arabs and Muslims with terrorism denied its Arab American characters access to their American cultural identity. Columbia Pictures’ Wrong is Right (1982), for instance, depicts an “Eye of Gaza” terror group bent on obliterating Tel Aviv and Jerusalem with atomic bombs. Arab American activists—presented as unnamed Arab students wearing garbs and keffiyehs—further illustrate the anti-Israeli grievances with a series of suicidal bombings in the United States. The bombings strike New York City, Texas, Chicago, Detroit, and Washington, DC. The film renders absent the humanity and rationality of Arab Americans, reducing them to mere reiterations of explosive emotionality under the slogans: “Jews own the television,” “Death to America,” and “Death to Israel.”

Despite the best intentions of director Richard Brooks to criticize the United States’ controversial foreign policy in the Middle East, captured in a reporter’s inquiry about the reasons behind the deterioration of America’s image, the visual treatment of Arab Americans is dismissive.

Hollywood’s representation strategy mainstreamed a public fear of the Arab and Muslim presence in the United States. Susan Akram, Steven Salaita, and Nadine Naber locate this fear within a history of anti-Arab racism in the United States.58 The depiction of Arab Americans as terrorists is persistent. William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in LA (1985) perceives a Muslim threat of assassination against the US president. Robert Zemeckis’ Back to the Future (1985) imagines the threat in the form of a moving van full of Libyans searching for nuclear weapons. William Riead’s Scorpion (1986) informs the audience of Palestinians targeting civilians, diplomats, servicemen, and military leaders. Gary Sherman’s Wanted: Dead or Alive (1986) implicates UCLA Arab students in a movie theater explosion killing at least 200 civilians including children, and plotting to unleash poison gas on Los Angeles population. John Myhers’ made-in-Israel film Terror in Beverly Hills (1988) shows Arabs kidnaping the US president’s daughter and other civilians in order to pressure Israel to release Palestinian prisoners. Lewis Teague’s Navy SEALs (1990) portrays the complicity of a Lebanese American journalist with terrorist groups overseas. James Cameron’s True Lies (1994) features a “Crimson Jihad” group in possession of six nuclear weapons set to cause havoc on US soil. Peter Segal’s Naked Gun 33 1/3: The Final Insult (1994) reveals an Arab plot to blow the 66th Annual Academy Awards. Stuart Baird’s Executive Decision (1996) dramatizes the threat in an airplane-hijacking scene with 406 passengers onboard including a US senator. These images, mostly concentrated in the action-adventure genre, locates Arab Americans through abstractions which position them as proxies of Arab foreign interests and regional anxieties. Examinations of Arab and Arab American interpretations of and responses to this genre emphasize its failure to recognize the nuance of the Arab and Muslim American communities.59

Even in Hollywood’s “nuanced” portrayals, Arab Americans’ cultural belonging is only presented through their renunciation of terrorism, which limits them within the good Muslim–bad Muslim binary. The American identity of Frank Haddad (Tony Shalhoub) in The Siege (1998) is enunciated through his patriotic duty as an FBI agent to preserve US national security. The appealing character of Layla Moore (Bridget Moynahan) in The Recruit (2003) draws from her dedication to her duty as a CIA agent. The Sentinel (2006) depicts Aziz Hassad (Raoul Bhaneja) as a hardworking Arab American patriot whose work as a Secret Service agent prompts him to risk his life and save the US president from a plotted assassination. In Five Fingers (2006), Ahmat (Laurence Fishburne) initially appears as a Moroccan terrorist torturing a Dutch pianist, but eventually emerges as a CIA agent involved in a counter-terrorism mission. Identifying Samir Horn (Don Cheadle) in Traitor (2008) as a Muslim hero is underscored through his performance as a US anti-terrorism intelligence contractor. The films identify good Arab and Muslim Americans in relation to their government service, which represents the pinnacle of patriotism. Their American citizenship is stressed only to the extent prescribed by national security politics.

Other depictions of Arab Americans fall within a cinematic critique of racial profiling. Escape from LA (1996) features a Muslim American Tasmila (Valeria Golino) being rounded up along with other “undesirable and unfit” citizens into a post-apocalyptic Los Angeles Island. In Land of Plenty (2004), Hassan (Shaun Toub) and his educated brother Youssef (Bernard White) endure public racial profiling by a Vietnam vet who embarks on a one-man mission to protect Los Angeles streets from terrorism. Ahmed (Assaf Cohen) and his two Middle Eastern friends are accused of kidnapping a little girl in Flightplan (2005); the film concludes with a reference to the non-Arab kidnappers. In The War Within (2005), Sayeed Choudhury (Firdous Bamji) rejects terrorism but his Middle Eastern looks lead him to detention. It is easy to carjack the unnamed cabbie (Yousuf Azami) in Crank (2006) by alleging his association with Al Qaeda, which prompts a man and two women to rush and beat him.60 In Sorry, Haters (2006), the patriot Muslim American Ashade Mouhana (AbdellatifKechiche) refuses pressures from a white woman to blow up government buildings; out of frustration, she harasses his family and pushes him under train tracks. In Pretty Persuasion (2004), Palestinian Randa (Adi Schnall) undergoes ridicule at high school, files alleged sexual assault accusations against her teacher, shames her family, and commits suicide. The Egyptian American Anwar El-Ibrahimi (Omar Metwally) in Rendition (2007) is a victim of the CIA extraordinary rendition program. The Muslim American Yusuf (Michael Sheen) wrestles with the issue of torture in The Unthinkable (2010). Dr. Fahim Nasir (Metwally) transforms from a suspect of terror in an airplane hijack attempt in Non-Stop (2014) to someone whose medical profession becomes a valuable asset in the rescue mission.

The two dimensions of patriotism and racial profiling mutually enforce recent efforts to appropriate the Arab American image and evade the critique laid against the industry’s circulation of terrorism-related images since the 1970s. This process—though appears to be promising to researchers and activists interested in shattering Hollywood’s monopoly over grounds of Americanness—perpetuates in seemingly nuanced ways a racialized imagery of Arab Americans entrenched in the unraveling politics of terrorism. Thus, the industry continues to retain its denial of the Arab and Muslim American communities the right to define their sense of belonging beyond its drawn nationalist boundaries of what constitutes an American sense of cultural citizenship. It reflects a systematic approach to locate Arab Americans within a post-Orientalist moral geography, defined by a nationalist codification of Israeli–US anti-terrorism rhetoric.

A FINAL NOTE

For decades, Hollywood’s projections of the Arab presence in the United States in terms of foreign policy and national security paved the ground for the post-9/11 backlash and the solidification of a threatening sense of lslamophobia. In his congressional speech following the 9/11 tragedy, President George W. Bush issued a sensational response to Americans’ most asked question about the terrorists, “why do they hate us?” He pondered:

They hate what they see right here in this chamber: a democratically elected government. Their leaders are self-appointed. They hate our freedoms: our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree with each other. . . These terrorists kill not merely to end lives, but to disrupt and end a way of life. With every atrocity, they hope that America grows fearful, retreating from the world and forsaking our friends. They stand against us because we stand in their way.61

The Bush administration’s prompt measures in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 further embraced racially informed strategies to counter the rising threat of homegrown terrorism. The preventive detention strategy resulted in the detention of 1,200 non-citizens of Arab and Muslim background. Not yet citizens, these individuals had no rights to contact their families or seek legal representatives, and they were sometimes subjected to physical and verbal abuse while in custody.62 The subsequent “special interest” designation opened doors for more arbitrary detentions. Thousands of interviews of Arab and Muslim visitors arriving in the United States since 2000 were held through the Department of Justice, while the FBI conducted 200,000 interviews by 2005.63 The Absconder Apprehension Initiative prioritized the removal proceedings of Arabs and Muslims in a deportation list that reached 314,000. The Special Registration program required Arab and Muslim nonimmigrants to register with the Department of Homeland Security, further unveiling efforts to suspect them as the enemy within.64

The post-9/11 trend of racial profiling in the context of terrorism also resulted in long-lasting strategies that continue to disfranchise the Arab and Muslim American communities. The PATRIOT Act (2001) granted US law enforcement agencies the authority to intrude into the daily lives of Arab and Muslim Americans.65 Law enforcement officers have been allowed to search their telephone, email communications, and records without court orders. They have also undertaken sneak and peek searches of homes and businesses without a warrant or even the owner’s or the occupant’s permission or knowledge. The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) have followed racially informed procedures that single Arab and Muslim immigrants and citizens for further investigation. These strategies are an extension of a War on Terror campaign that has legitimized renditioning suspects and subjecting prisoners of war, or as named enemy combatants, to inhumane treatment in violation of the Geneva Convention accords.66

Law enforcement agencies have been empowered with the authority to arrest American citizens who may be suspected of any terrorism-related connections through a strategy signed into law in the National Defense Act by President Obama on the eve of the 2012 New Year. The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) attempted to map the Arab and Muslim population and identify ways to quarantine the threat of homegrown terrorism. In New York, there were attempts to grant firefighters the right to inspect and search any apartment or housing unit occupied by any Arab American. A community facility in Irving, Illinois, was renamed the “Irving Mosque” for a drill involving thirty government agencies including the Illinois Law Enforcement Alarm System (ILEAS). Storming the “mosque” with an armored vehicle, the officers rescued a hostage tied to explosive devices, and killed the Muslim terrorist, who happened to carry an Arab name.67

The US cultural industry has played a significant role in mediating this haunting conflation. Media coverage of Arab and Muslim Americans has been mostly constrained to issues related to terror incidents. Even when coping with grief, appeals to multicultural America as a ground of national unity usually dismissed featuring Arabs and Muslims as part of the American cultural mosaic.68 Liberal television shows like Real Time with Bill Maher as well as conservative programs like The O’Reilly Factor, The Glenn Beck, Just in with Laura Ingraham, and Hannity’s America, and radio talk shows like The Rush Limbaugh Show, and The Savage Nation are some of many media productions that have delivered various expressions of Islamophobia. Fiction writers have used their imaginative power to depict Arab Americans as a source of trouble for the United States. John Updike’s Terrorist (2004) and Robert Ferrigno’s Prayers for the Assassin (2006) offer examples of lslam as a source of threat to the US national security. As argued by Evelyn Alsultany, television shows produced in the post-9/11 context incorporated “simplified complex” representation strategies that further contributed to the racialization of Arab Americans and restricted them within the citizen-terrorist trope.69 In his only presidential visit to an American Muslim mosque, Barrack Obama criticized the industry’s representation priorities. “Our television shows,” he emphasized, “should have some Muslim characters that are unrelated to national security.”70

The conflation of Arabs and Muslims in the United States with foreign policy and terrorism has instilled fear in the public of Arab and Muslim presence, resulting in an alarming increase in the reported cases of violence, harassment, threat, and attack.71 Fighting terrorism has become, in fact, a contemporary phase of racial discrimination in the history of Arab immigration experience. Post-9/11 civil liberty reports by the ADC show a dramatic increase in anti-Arab, racially driven attacks in the United States.72 The Council of American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) has issued annual civil rights reports since 1995 that capture this sentiment.73 Targeted in their place of work, place of worship, and in the downtowns and suburbs of their cities and towns, Americans with Middle Eastern looks have experienced an unavoidable, bitter sense of post-9/11 visibility. Victims of the Oak Creek shooting (2012) and Chapel Hill shooting (2015) exhibit such public antagonism.

Positive results of such backlash have materialized in a slow growth of public disillusionment in the conflation and in a rising sense of activist dedication in the Arab and Muslim American civil society. Hollywood’s popularized imagery of Arab and Muslim Americans has, however, remained a popular and financially lucrative source of a limited and limiting reading of American cultural citizenship, one which continues to restrict Arab Americans’ boundaries of belonging beyond the movie screen. The representation patterns once initiated in the 1970s have sustained portrayal modes that suspend the complexity of Arab American imagery and constrain it within marketable consumptions of fear and insecurity. Consequently, Hollywood’s nationalist framework conserves a tradition of reduction, minimizing US–Arab and Arab–Israeli transnational politics into a simplified nationalist framework around issues of home, land, and security. This framework simultaneously casts Arab Americans as the cultural Other and feeds an alarming growth of Islamophobic rhetoric in the country.

NOTES

Moustafa Bayoumi, How Does it Feel to be a Problem? Being Young and Arab in America (New York: The Penguin Press, 2008), 5.↩︎

Toby Miller defines the cultural citizen as “the virtuous political participant who is taught how to scrutinize and improve her or his conduct through the work of cultural policy;” see, The Well-Tempered Self: Citizenship, Culture, and the Postmodern Subject (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), xxi. Examples of works shedding lights on this role of popular culture include Laura Wexler, Tender Violence: Domestic Visions in an Age of US Imperialism (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000); Adris Cameron, ed., Looking for America (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2005); Rachel Rubin and Jeffrey Melnick, Immigration and American Popular Culture: An Introduction (New York: New York University Press, 2007).↩︎

Louis Althusser, “Ideology and the Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation),” in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2001, first published 1970), 85–126.↩︎

My engagement with the term “cultural citizenship” interacts with Aihwa Ong’s definition of this type of citizenship as the “cultural practices and beliefs produced out of negotiating the often ambivalent and contested relations with the state and its hegemonic forms that establish the criteria of belonging within a national population and territory.” See “Cultural Citizenship as Subject-Making: Immigrants Negotiate Racial and Cultural Boundaries in the United States,” Current Anthropology 37, no. 5 (December 1996): 737–62, 738.↩︎

Lary May, The Big Tomorrow: Hollywood and the Politics of the American Way (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2000), 1. See also Lary May, ed., Recasting America: Culture and Politics in the Age of Cold War (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1989).↩︎

Peter Rollins and John E. O’Connor, eds., Hollywood’s Indian: The Portrayal of the Native American in Film (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999); Alfred Charles Richard, Contemporary Hollywood’s Negative Hispanic Image: An Interpretive Filmography, 1956–1993, annotated edition, (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1994); Robert G. Lee, Orientals: Asian American in Popular Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999); Gina Marchetti, Romance and the “Yellow Peril”: Race, Sex, and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994); Alan Casty, Communism in Hollywood: The Moral Paradoxes of Testimony, Silence, and Betrayal (Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2009); Ed Guerrero, Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993); Lester D. Friedman, The Jewish Image in American Film (Secaucus: Citadel Press, 1987).↩︎

Jack G. Shaheen, Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People (New York: Olive Branch Press, 2001); Guilty: Hollywood’s Verdict on Arabs after 9/11 (New York: Olive Branch Press, 2008). See also, Laurence Michalak, Cruel and Unusual: Negative Images of Arabs in American Popular Culture (Washington, DC: American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, n.d.); Matthew Bernstein and Gaylyn Studlar, eds., Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1997); Tim John Semmerling, ‘Evil’ Arabs in American Popular Film: Orientalist Fear (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006).↩︎

Melani McAlister, “Introduction,” in Epic Encounters: Culture, Media, and US Interests in the Middle East since 1945, 2nd ed., (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 1–39; Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1994, first published in 1979).↩︎

Abdelmajid Hajji, Arabs in American Cinema (1894–1930): Flappers Meet Sheikhs in New Movie Genre (United States: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013), 9; for a discussion about the rise of spectatorship for Hollywood’s consumption, refer to Miriam Hansen, Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991).↩︎

McAlister, Epic Encounters, Introduction, 1–39.↩︎

Laurence Michalek, “The Arab in American Cinema: A Century of Otherness,” Cineaste: Americ’as Leading Magazine on the Art and Politics of the Cinema 17, no. 1 (1989): 3–9, 3.↩︎

For a comprehensive list of the films, refer to Shaheen, Reel Bad Arabs.↩︎

Only six minutes of the full-feature film survived. The silent cinema entertained Orientalist images of Arab Americans in the short film Arabian Dagger (1908), which shows less interest in the peddler than his dagger, and The Syrian Immigrant (1920) documentary. For more about these works, see Hajji, Arabs in American Cinema, 11.↩︎

Alixa Naff, Becoming American: the Early Arab Immigrant Experience (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985), 247–63.↩︎

The whiteness of Arabs hailing from the Arabian Peninsula was not legally recognized until the 1940s. See Mustafa Bayoumi, “Racing Religion,” CR: The New Centennial Review 6, no. 2 (Fall 2006): 267–93.↩︎

Hajji, Arabs in American Cinema, 11–12.↩︎

The numbers are reported in the Proclamation by the President of the United States (22 March 1929) as published in Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 28–29.↩︎

The second wave contained 2,924 Palestinian refugees along with limited arrivals of Arab laborers. See Louise Cainkar, Homeland Insecurity: The Arab American and Muslim American experience after 9/11 (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2009), 79.↩︎

Arab American Institute Foundation, “Quick Facts about Arab Americans,” accessed 4 February 2016, http://b.3cdn.net/aai/fcc68db3efdd45f613vim6ii3a7.pdf.↩︎

Rashid Khalidi, Sowing Crisis: The Cold War and American Dominance in the Middle East (Boston: Beacon Press, 2009), 181; Malcolm H. Kerr, The Arab Cold War: Gamal ʿAbd al-Nasir and His Rivals, 1958–1970 (London: Oxford University Press, 1971).↩︎

The Egyptian–Saudi contestation between republican and kingdom governing structures in countries like Yemen is an example of such local conflicts. See Jesse Ferris, Nasser’s Gamble: How Intervention in Yemen Caused the Six-Day War and the Decline of Egyptian Power (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013).↩︎

Nakba is the Arabic word for “catastrophe.”↩︎

Naksa is the Arabic word for “setback.”↩︎

OAPEC members included Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Qatar, and Syria.↩︎

John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt, The Israel Lobby and US Foreign Policy (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007).↩︎

For more about the impact of the 1967 war, read William B. Quandt, Decade of Decisions: American Policy Roward the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1967–1976 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977).↩︎

Lee Pfeiffer and Philip Lisa, The Films of Sean Connery (New York: Citadel Press, 2001), 160.↩︎

My use of the word “reel” echoes Shaheen’s usage, which signifies Hollywood’s stereotypical image of Arabs: see Reel Bad Arabs.↩︎

Khalil’s second UN speech: see Next Man, directed by Richard Sarafian (Los Angeles: Artists Entertainment Complex, 1976).↩︎

The film received four Academy Awards and was praised for the originality of its screenplay. The Network, directed by Sidney Lumet (Los Angeles: Metro-GoldwynMayer and United Artists, 1976).↩︎

Kathleen Fitzpatrick, “Network: The Other Cold War,” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies 31, no. 2 (2001): 33–39, 36.↩︎

9/11 generated a very important moment for the television to play a viable role in spurring such a sense of patriotism, see Lynn Spiegel, “Entertainment Wars: Television Culture after 9/11,” American Quarterly 56, no. 2 (June, 2004): 235–70.↩︎

Roland Barthes, Mythologies (Hill and Wang: New York, 1972).↩︎

Laurie Goodstein and Thomas Kaplan, “Donald Trump Calls for Barring Muslims From Entering US,” The New York Times, 7 December 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/politics/first-draft/2015/12/07/donald-trump-calls-forbanning-muslims-from-entering-u-s/.↩︎

Craig Hight, “‘It isn’t always Shakespeare, but it’s genuine’: Cinema’s Commentary on Documentary Hybrids,” in Understanding Reality Television, eds. Su Holmes and Deborah Jermyn (New York, Routledge, 2004), 233–51, 235–36.↩︎

Nadine Naber, “Introduction: Arab Americans and US Racial Formations,” in Race and Arab Americans Before and After 9/11: From Invisible Citizens to Visible Subjects, eds. Nadine Naber and Amany Jamal (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2008), 1–45, 35.↩︎

Ibid., 35.↩︎

As cited by Michalek, “The Arab in American Cinema,” 9.↩︎

Ibid., 9.↩︎

For a reading of Hollywood’s history of associating Arabs with animals, see Waleed F. Mahdi, “Marked Off: Hollywood’s Untold Story of Arabs and Camels,” in Muslims and American Popular Culture, vol. 1, eds. Anne R. Richards and Iraj Omidvar (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2014), 196–223.↩︎

Marita Sturken argues that national trauma defines collective memory. See Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic and the Politics of Remembering (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 2–3.↩︎

Carl Boggs and Tom Pollard, “Hollywood and the Spectacle of Terrorism,” New Political Science, 28, no. 3 (2006): 335–51, 337.↩︎

Melani McAlister, “A Cultural History of the War without End,” The Journal of American History 89, no. 2 (2002): 439–55, 440.↩︎

Michalek, “The Arab in American Cinema,” 5.↩︎

See Edward Said on Orientalism, directed by Sut Jhally (Media Education Foundation, 1998); Hatem I. Hussaini, “The Impact of the Arab-Israeli Conflict on Arab Communities in the United States,” in Settler Regimes in Africa and the Arab World: The Illusion of Endurance, eds. Ibrahim Abu-Lughod and Baha Abu-Laban (Wilmette: The Medina University Press International, 1974), 201–20.↩︎

Edward Said, “The Arab Portrayed,” in The Arab-Israeli Confrontation of June 1967: An Arab Perspective, ed. Ibrahim Abu-Lughod (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1970), 1–9, 2, and 6.↩︎

Gary C. David, “The Creation of ‘Arab American’: Political Activism and Ethnic (Dis)Unity,” Critical Sociology 33, no. 36 (2007): 833–62.↩︎

Another Arab American organization established prior to 1967 was Women concerned about the Middle East (NAJDA), founded in 1960.↩︎

Pamela Pennock, “Third World Alliances: Arab-American Activists in American Universities, 1967–1973,” Mashriq & Mahjar 2, no. 2 (2014): 55–78; Keith P. Feldman, A Shadow over Palestine: The Imperial Life of Race in America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015).↩︎

The NAAA was founded in 1972, the ADC in 1980, and the AAI in 1985.↩︎

Shaheen, Reel Bad Arabs, introduction.↩︎

Andrew Stewart, “How Cannon Films Demonizes Arabs,” Counterpunch, 25 December 2015, http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/12/25/how-cannon-filmsdemonizes-arabs/.↩︎

See McAlister, “A Cultural History of the War without End,” 450.↩︎

Ella Shohat, Israeli Cinema: East/West and the Politics of Representation (London: I.B.Tauris, 2010, originally published in 1989).↩︎

Nix, “Air Marshal (2003) Movie Review,” Beyond Hollywood, 24 September 2003, http://www.beyondhollywood.com/air-marshal-2003-movie-reviewI.↩︎

Shaheen, Reel Bad Arabs, 27.↩︎

Nabeel Abraham, “Anti-Arab Racism and Violence in the United States,” in The Development of Arab-American Identity, ed. Ernest McCarus (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994), 155–209, 180.↩︎

Susan M. Akram, “The Aftermath of September 11, 2001: The Targeting of Arabs and Muslims in America,” Arab Studies Quarterly 24, no. 2&3 (Spring/Summer 2002): 61–118; Steven Salaita, Anti-Arab Racism in the USA: Where it Comes from and What it Means for Politics Today (London: Pluto Press, 2006); Naber, “Introduction: Arab Americans and US Racial Formations,” 2008.↩︎

Karin Gwinn Wilkins, Home/Land/Security: What We Learn About Arab Communities From Action-Adventure Films (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2009); Juliana Gaipo-Marbet, The Nature and Impact of Stereotyping of Arabs in American Society: Recognizing Arab Perspectives (PhD dissertation, University of Virginia, 2001).↩︎

The earliest film depicting Arab Americans as taxi-drivers is Quick Change (1990). The taxi driver in this film (Tony Shalhoub) does not speak English. His gibberish and strange actions emphasize the liminality of the Arab American space in the imaginations of directors Bill Murray and Howard Franklin.↩︎

George W. Bush, “A Nation Challenged: President Bush’s Address on Terrorism before a Joint Meeting of Congress,” The New York Times, 21 September 2001, http://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/21/us/nation-challenged-president-bush-saddress-terrorism-before-joint-meeting.html.↩︎

Personal narratives provided in Bayoumi, How Does it Feel to be a Problem?↩︎

The estimate is provided by the director of the Center for International Studies at MIT, John Tirman in his piece “Security the Progressive Way,” The Nation, 11 April 2005; quoted in Cainkar, Homeland Insecurity.↩︎

Cainkar, Homeland Insecurity, 2009.↩︎

An acronym for the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism.↩︎

For more about the Arab and Muslim American post-9/11 civil rights crisis, see Elaine C. Hagopian, ed., Civil Rights in Peril: The Targeting of Arabs and Muslims (Chicago: Haymarket Books and London: Pluto Press, 2004).↩︎

Cainkar, Homeland Insecurity; Aladdin Elaasar, Silent Victims: The Plight of Arab & Muslim Americans in Post-9/11 America (Bloomington: Author House, 2004).↩︎

Evelyn Alsultany, “Selling American Diversity and Muslim American Identity through Nonprofit Advertising Post-9/11,” American Quarterly 59, no. 3 (September 2007): 593–622.↩︎

Evelyn Alsultany, Arabs and Muslims in the Media: Race and Representation after 9/11 (New York: New York University Press, 2012); Leti Volpp, “The Citizen and the Terrorist,” UCLA Law Review 49, no. 5 (2002): 1575–1600.↩︎

Barak Obama, “Remarks by the President at Islamic Society of Baltimore,”The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, 3 February 2016, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/02/03/remarks-president-islamicsociety-baltimore.↩︎

For a reading of the racial violence on the day following 11 September 2001, see Muneer Ahmed, “Homeland Insecurities: Racial Violence the Day after September 11,” Social Text 20, no. 372 (Fall 2002): 101–15.↩︎

Hussein Ibish, 1998-2000 Report on Hate Crimes and Discrimination against Arab Americans (Washington, DC: ADC Research Institute, 2001); Hussein Ibish, Report on Hate Crimes and Discrimination against Arab Americans: the post-September 11 Backlash, September 11, 2001–October 11, 2002 (Washington, DC: ADC Research Institute, 2003).↩︎

CAIR, Civil Rights Reports, accessed 4 February 2016, https://www.cair.com/civil-rights/civil-rightsreports.html.↩︎