Michelle Baroody

THE SPHINX TAKES MANHATTAN, OR THE SIGNIFICANCE OF A “MAN FROM THE YAMAN” IN AMEEN RIHANI’S ARABIAN PEAK AND DESERT

Abstract

In 1989, a replica of the Great Sphinx of Giza was photographed passing in front of the Statue of Liberty. This image recalls neglected imperial histories and challenges global models of center and periphery. A similar encounter occurs at the beginning of Ameen Rihani’s work Arabian Peak and Desert: Travels in Al-Yaman, where the early twentieth century Syrian American scholar writes of a chance meeting with a “man from the Yaman.” Their conversation is brief, yet it colors the travel narrative that follows. In this paper, I read these encounters together to situate moments of “reply” to Orientalist discourses. These encounters simultaneously reproduce and displace Eurocentric histories and epistemologies by creating a space that is both within and outside modern narratives of progress. This paper analyzes the two encounters and proposes montage as a method for reexamining literary and visual texts.

INTRODUCTION

Method of this project: literary montage. I needn’t say anything. Merely show. I shall purloin no valuables, appropriate no ingenious formulations. But the rags, the refuse-these I will not inventory but allow, in the only way possible, to come into their own: by making use of them.

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project1

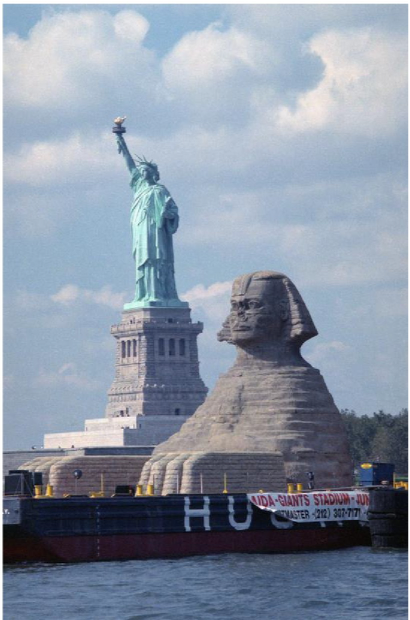

This paper is framed by two encounters and the connections made in each. The first is displayed in the photograph below:

This image depicts the Great Sphinx of Giza resting on a barge in New York Harbor, its stoic gaze fixed prophetically ahead as it drifts slowly past the iconic Statue of Liberty. Contrary to appearance, this is not a Photoshopped homage to the world’s largest miniature golf course, but an “actual if unlikely event” captured by photographer Henry Abrams in 1989.3 As Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby describes it in her work Colossal, “an eight-ton replica of the Sphinx was loaded onto a barge that circled New York Harbor to promote a production of Aida, Verdi’s Orientalist opera about doomed lovers in Old Kingdom Egypt.”4 She notes that Abrams “must have known he had a great picture when he pointed his camera. . . [b]ut he was probably unaware [that] he was witnessing a reenactment of an all but forgotten episode in nineteenth-century history.”5 As Grigsby suggests, the photo simultaneously recalls Lady Liberty’s Oriental roots and provides a visual reference point for a material and allegorical meeting of the ancient East and the modern West processed through genuine photographic emulsion.6

The second encounter is extracted from the opening lines of Ameen Fares Rihani’s travelogue, Arabian Peak and Desert: Travels in Al-Yaman:

One day, at the office of an Arabic newspaper in New York, I met a man who spoke Arabic with a soft unfamiliar accent, and I was curious to know where he was from. His reply was more interesting than his speech. It was even surprising. For seldom does one see in the Syrian Colony of New York a man from the Yaman; and as I was then on the eve of departure for Arabia, I availed myself of the opportunity of adding something to my little store of knowledge.7

Published in 1930, this text is part of Rihani’s English-language trilogy that chronicles the author’s journey from New York to the Arabian Peninsula in the 1920s.8 Rihani was born in Freike, a small village on Mount Lebanon, on 24 November 1876. His hometown, now located in the country of Lebanon, was then part of the Ottoman territory known as Greater Syria. In 1888, at the age of twelve, Rihani immigrated to New York, where he later became one of the most prolific Syrian-born American intellectuals in the early twentieth century. Arabian Peak is one of his most globally significant projects; it is a first-person narrative that provides an account of the political situation and rulers in Yemen after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. Principally, the work is a travelogue that blends philosophy, ethnography, and poetry to recount Rihani’s position in favor of Arab Nationalism.9

I place these encounters alongside one another for a closer examination of the histories they track as they move between the so-called ‘Arab world’ and America. On the surface, both episodes resituate a figure who is rooted in the past, a symbol of the traditionally non-modern—the Sphinx and the “man from the Yaman”—into the modern, cosmopolitan space of New York City. Cited as “surprise” in Rihani’s text and archived as irony in the photograph, each intersection contends with modern narratives of progress, which tend to favor Western versions of history. However, the juxtaposition of histories, epistemes, and geographical spaces in each singular exchange offers a unique moment of revision to Eurocentric accounts of the past and present. I am interested in the ostensible and deliberate collisions between West and non-West, but more so in the unexpected figures and discourses that are exposed by these instances. Consequently, I read these encounters as illustrations of montage, a term that I frame through the work of Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein and German philosopher Walter Benjamin.

As a literary and cinematic tradition, montage does not speak but “shows,” as Benjamin suggests in the epigraph above.10 It is a method that “makes use of’ words and images, rather than merely “inventory” their appearance; instead, montage allows each part “to come into [its] own.”11 According to Eisenstein, montage is more deliberate. He suggests that montage is the practice of “comparison,” an arrangement of images that simultaneously presents “juxtaposition and accumulation, in the audience’s psyche.”12 These comparisons form “associations that the film’s purpose requires, associations that are aroused by the separate elements of the stated (in practical terms, in ‘montage fragments’) fact, associations that produce, albeit tangentially, a similar (and often stronger) effect only when taken as a whole.”13 This is not the montage of contemporary Hollywood films, which most often use the process of placing images alongside one another to represent the passage of time. Instead, this is a technique that “the film’s [larger] purpose requires.”14 For Eisenstein, the method is specific to political cinema. However, his theoretical approach to the process of editing suggests a strategy for reading modern works of art more generally. When figures are placed together, the reader or audience makes associations between them even if they seem unrelated. In writing and filmmaking these decisions often have specific intentions and desired effects—in fact, Eisenstein’s use of montage was meant to construct images of revolution in the “audience’s psyche” to inspire continual uprising against the State.15 But it is inevitable that the text will also produce meanings that were never intended, readings that vary based on the conditions of reception and historical resonances.

The effect of montage relies on two often unconscious and simultaneous effects: “juxtaposition”—the act of placing images next to one another—and “accumulation”—building on top of what is already there. Framed together or in succession, the elements appear to be precisely where they belong, and yet, at the same time their connection feels contrived. The contradiction forms an “association” between images and words, and as the fragments become textually linked, meaning is produced. As a critical apparatus for reading literary and visual encounter, montage is a mode of looking at images together to tease out various levels of implied meaning; it is a method that pays close attention to both the visible and invisible narratives in a text.16

Benjamin’s work builds on Eisenstein’s theory. While Benjamin’s montage is a literary practice, it is more concerned with “show[ing]” connections rather than “say[ing] anything” definitive about the text in question.17 Instead, implicit meanings are generated through reading and “the rags, the refuse,” the discarded elements of history, are able to “come into their own. . . by making use of them.” In The Arcades Project, Benjamin’s unfinished opus, the text itself is presented in the form of fragments, edited together with no clear “formulation” in mind. “Literary montage” is the organizing principle of this broken and disjointed text, an effective demonstration of “method” that may or may not be intentional. Since Benjamin died before finishing the content of The Arcades, it is unclear whether or not he would have filled in the gaps between aphorisms. Regardless, within each microcosm, the reader is invited to come to his text without taking “inventory”; they are asked to “purloin no valuables,” but to “make use” of the work by reading around, through, and in between fragments. While this “formulation” insists that it is not offering any “ingenious” approach, it presents a way of reading texts and images together that does not rely on preconceived definitions and ideas. However, it does not assume that these are absent either. In Benjamin’s method, montage takes the reader’s preexisting associations and reads signification through them without affixing a singular or definitive meaning to the pieces or the whole. This process of reading recognizes structure and language, but also maintains the text’s multiplicity.18

I propose that this method is fundamental to reading the global movements and unforeseen exchanges in Rihani’s and the Sphinx’s encounters. The associations made do not merely locate a space-time in the linear trajectory of historical modernity; instead, these moments underscore the “juxtapositions and accumulations” that emerge from the multiple spaces and times contained within each singular text.19 The resulting images disrupt dominant histories by aligning two or more figures that are not likely to meet in one place or time except through deliberate anachronisms. And yet, in contemporary registers, the two cultures and places represented by these characters meet regularly: in the news, in wars and occupations, in film and television, in everyday experience. In fact, Edward Said argues in Orientalism that the dialectic relationship between the ‘Arab world’ and America is constitutive of each side’s reality. The “United States today is heavily invested in the Middle East,” Said suggests, “more heavily invested than anywhere else on earth.” And this “investment” is “imbued with Orientalism.”20 Its methods and language may go unnoticed, as “Orientalism now” is “dressed up in policy jargon.”21 But the contemporary frame still locates the Orient and its people as always in relation to Euro-American modernity and superiority; the East is “an imitation of the West which can improve” only with the help of modernization and intervention.22

Said’s work is formative to postcolonial studies, but is often read as offering a monolithic notion of Orientalism. To counter these reductive tendencies, I follow thinkers, such as Lisa Lowe, who have taken up Said’s definition and expanded on the diversity of Orientalist discourses that continue to reproduce neo-colonial formulations of self and Other, West and East.23 For example, in Critical Terrains: French and British Orientalisms, Lowe argues that “orientalism is not a single developmental tradition but is profoundly heterogeneous. French and British figurations of an oriental Other are not unified or necessarily related in meaning, they denote a plurality of referents.”24 French, British, and American discourses about the Orient determine how the spaces and peoples associated with its terrains are imagined, understood, and regarded in terms of history, politics, and culture. Additionally, the Orient is embedded and reproduced through a host of other discourses related to economic, social, and aesthetic concerns-the ‘Orient’ is not just several places or several people, it is a varied system of dominance that takes on myriad cultural forms and geopolitical strategies.

In order to revise the global unevenness that still exists between the ‘Arab world’ and America, it is necessary to “unthank” Western-centered notions about both places and to reframe the ideological and political dimensions of the East/West binary.25 However, as Ella Shohat and Robert Stam suggest in Unthinking Eurocentrism, “so embedded is Eurocentrism in everyday life, so pervasive, that it often goes unnoticed. The residual traces of centuries of axiomatic European domination inform the general culture, the everyday language, and the media, engendering a fictitious sense of the innate superiority of European-derived cultures and peoples.”26 Thus, part of this project must take into account the Western-centric motivations to read objects from or about the ‘Arab world’ as if they are imitations of or subjects to “axiomatic European domination.” As I will demonstrate, the juxtapositions evident in the two encounters discussed here simultaneously resist and reproduce both sides of the dialectic. By reading through their multiple narratives, this project aims to uncover how each meeting creates a moment of “reply” to essentialist formations and cultural appropriations, proposing a different way of being in the world that is not immediately subsumed by Euro American hegemony.27

As montage, I read these literary and visual encounters as instances of modern knowledge production, rather than appropriations by the West of non-Western ways of knowing. These moments call into question the very notion of modern progress, a historical trajectory of development—economic and political—that is ostensibly affixed to Western nations and viewed as latent or underdeveloped in places like the Middle East and North Africa. In Rihani’s and the Sphinx’s encounters, the reader/viewer is required to engage with a paradox where modernity’s discursive incommensurabilities between the concepts of the ‘Arab world’ and America are temporarily suspended and thrown into flux. As a result, it is impossible to ignore the juxtaposition of imperial and Orientalist discourses in each that simultaneously preserve and destabilize Western dominance.

The “surprising” presence of the Other registers the collisions between Arab nations and America and restructures how we see and read each text; the uneven relations of power make the multiplicity of these discourses visible. While the Statue of Liberty and Rihani metonymically stand in for American freedom and advancement, both are also interpolated by the presence of the stranger. Each is reframed by the contrived and ironic comparison to the Other-displaced figures from Arabia and North Africa. Lady Liberty’s modern origins and metallic construction become unmistakable with the arrival of the noticeably ancient, limestone colossus. In Rihani’s text, the passage’s placement in the larger work—these are the opening lines—highlights the distinction between the men. The Yemeni man is marked as a foreigner from the deserts of “Arabia,” which reasserts the author’s position as a cosmopolitan Syrian American at home in the modern metropolis. Each encounter’s cultural intelligibility is overwhelmingly multiplied by the unexpected associations that emerge from history’s forgotten fragments.

THE STATUE, THE SPHINX, AND THE CLASH OF CULTURAL IMAGES

The great face was so sad, so earnest, so longing, so patient. There was a dignity not of earth and its mien, and in its countenance a benignity such as never any thing human wore. It was stone, but it seemed sentient. If ever image of stone thought, it was thinking. It was looking toward the verge of the landscape, yet looking at nothing—nothing but distance and vacancy. It was looking over and beyond every thing of the present, and far into the past. It was gazing out over the ocean of Time—over lines of century—waves which, further and further receding, closed nearer and nearer together, and blended at last into one unbroken tide, away toward the horizon of remote antiquity.

Mark Twain, The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrims’ Progress28

Mark Twain’s description of the Sphinx in The Innocents Abroad, his nineteenth century travelogue to the ‘Holy Land,’ describes the structure as if it is able to see beyond the present “toward the horizon of remote antiquity.” The Sphinx is not resting in history, but “thinking,” albeit in terms that are incomprehensible to the modern-day onlooker. In the shadow of the ancient colossus, Twain—the cosmopolitan American author who is often critical of the landscapes and peoples he meets on his trip East—stands in awe. As he describes it, the Sphinx’s gaze appears impervious to “the ocean of Time,” and its look, always positioned ahead, seems capable of witnessing the whole course of history in each passing moment. The Sphinx is a figure that stands both in and outside of historical time: its continued existence illustrating a convergence of moments that grow “nearer and nearer” until they are “blended at last into one unbroken tide.” It is not just longevity that impresses Twain as he glimpses Egyptian antiquity, it is the Sphinx’s relationship to what comes later: to progress in modern architecture and art, to the history and preservation of empires, and to the knowledge of the ancient world.

By 1989, when the photograph in New York Harbor was snapped, the Sphinx was likely as well known in American culture as Lady Liberty herself. In large part, this is due to travel accounts like Twain’s, whose interest in Egypt was piqued, along with many other Westerners, by Napoleon’s 1798 invasion into North Africa. For America, though, this moment was of particular importance according to Scott Trafton, whose work in Egypt Land draws connections between the resulting Egyptomania in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the formation of economic, political, and social structures in the burgeoning United States. Trafton suggests that “writing a history of American interest in ancient Egypt approaches the condition of attempting to write a history of America itself.”29 He bases this conclusion largely on “timing: with the Louisiana Purchase . . . only five years after 1798, Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt coincided almost exactly with the earliest explorations of the American West . . . [a notion] further cemented by the immediately exported analogy between the Nile and the Mississippi.”30 While Trafton’s research is focused on demonstrating how early American interest in Egypt led to a system of racism, slavery, and segregation in the United States, his focus on the concomitance of Napoleon’s ‘rediscovery’ of ancient Egypt with the creation of the American state gives the New World a reflection of its own goals through an imagined narrative of antiquity’s surviving fragments.

Therefore, when the Sphinx arrives in New York Harbor in 1989, America’s past and present imperial interests in the Middle East/North Africa are revived; interests that, as Trafton argues, were there from the United States’ historical beginnings. Moreover, the visual encounter of the Sphinx and the Statue is a still picture, which makes it the representation of an event that occurred at a particular moment in historical time. Thus, the meeting is archived in the material snapshot, allowing the image to exist beyond its initial occurrence. As a photograph, it is already a copy, a facsimile of non-verbal objects placed together and enclosed by clearly-defined borders. The frame, which is cropped to include these two figures as focal points, sets the terms by which the encounter can re-envision the boundaries of what is produced. Moreover, the photo’s visual content is an instance of global modernity, as the timeless Sphinx meets the Statue of Liberty in the center of American tourism and immigration. Arriving by boat in the harbor famous for welcoming new emigres to America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Sphinx recreates the history of immigration on a colossal scale.

The “eight-ton replica” of the Sphinx was built to promote “a production of Aida, Verdi’s Orientalist opera.”31 But before hitting the stage, the Sphinx first took New York waters by storm, making visible an epic relationship and unresolved clash of modern civilizations. This collision not only emphasizes the long history of Western appropriation of Eastern accomplishment, but it draws on one of the most iconic examples of this: the Sphinx and Ancient Egypt.32 In 1989, in a modern city like New York, the ship arrives as an outdated mode of travel, a detail that merely emphasizes the anachronistic approach of the Egyptian monument-an immigrant so recognizable there is no need for a passport.33 Elliot Colla’s discussion of the Egyptian Sculpture Room at the British Museum expands on this point. His introduction to Conflicted Antiquities offers an analysis of the relationship between ancient artifacts on display and the museum-goers who come to look upon their antiquity—a gaze similar to Twain’s in Innocents Abroad at the sight of the Sphinx. Colla states, “in sum, [museum displays] routinely describe the objects as the site of an experience in which objects are bearers of their own meaning and active participants in the event. In this reading, the Egyptian artifacts appear to run the show, subjecting British museum-goers to the image of Egyptian grandeur they embody.”34 However, the museum “directs aesthetic experience”—it determines the value of objects on display and creates the conditions in which they are consumed.35 The main objective of the sculpture room is “conservation” of this unique history, which is folded into the narrative of European colonial enterprise in “Oriental” lands.36 Ancient Egypt becomes part of the European imaginary: “Western representations of Egypt . . . [that] stress the ancient grandeur of the ancient kingdom at the expense of contemporary Arab lives.”37

When the Sphinx arrives in New York Harbor it carries with it cultural resonances and appropriations, and it is also recognizable because of them. Its entry is not questioned because Americans feel that they know its place in history, a history that is disconnected from “contemporary Arab lives,” but included within larger narratives of progress. The Sphinx’s entrance to America is granted partly because it is considered separate from those currently living in Egypt, whose everyday lives have been transformed and determined by colonial conquest, which includes a displacement and removal of its artifacts.38 The actual situation in Egypt is contorted to fit a narrative of Euro-American dominance and progress in relation to modern constructions like the Statue of Liberty. The boat on which it arrives simultaneously highlights and stands in opposition to the modern/ancient distinction between the colossi: it is the Sphinx’s mobility in this image that disrupts the Statue’s message of freedom and equality. The greatness of Egypt’s past is ripped from its origins to fit a story of modern progress in the West, and in the process it is alienated from individuals currently living in Egypt.

The occasion in the photograph-promotion for a production of Aida-generates other readings of note. The first is organized around the movements of global capital: the Italian Orientalist opera is performed in an American city represented by Ancient Egypt and marketed to locals, visiting Americans, and international tourists. The history of Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida is particularly interesting in this context, as Khedive Isma’il Basha of Egypt originally commissioned the opera for the grand opening of the Royal Opera House in Cairo in 1869. The event was meant as a celebration of the completed construction of the Suez Canal, a waterway built by the French to connect the Mediterranean to the Red Sea, allowing easy access between Europe and Southeast Asia. Verdi declined the invitation to pen a new opera and composed a hymn for the venue’s opening instead. However, two years later, in 1871, Aida’s first performance took the stage at the Royal Opera House in Cairo.39

The historical situation of Aida’s composition contributes to the maintenance of an Egypt rooted in the past, one that is upended when the mobile Sphinx passes by the stationary Statue. Said argues in Culture and Imperialism, “as a visual, musical, and theatrical spectacle, [Aida] does a great many things for and in European culture, one of which is to confirm the Orient as an essentially exotic, distant, and antique place in which Europeans can mount certain shows of force.”40 Moreover, the hegemonic narratives penetrate Egypt as well, since an Italian composer, Verdi, was commissioned to write the first performance at Cairo’s opera house. The “exotic, distant, and antique” representations of Ancient Egypt created by the European imaginary and performed to upper class Egyptians; the Orientalist narrative shifts between Egypt, Europe, and America to find itself back in Egypt, the quasifictional source of its inspiration. In Aida, the spectator witnesses an entrenched history through cultural production, one that is recalled and revised in New York in 1989.

In an interview, Grigsby suggests that the Statue of Liberty and the Suez Canal “are a key way to look at imperialism. They each generate just what imperialism could do: Build [sic] projects that changed the world, sometimes at immense costs to human lives.”41 As the Sphinx and Lady Liberty come together, this “immense cost” is revealed through juxtaposition. Two unlikely and uneven spaces—Egypt and America—are simultaneously witnessed through a singular moment in 1989, an event that is repeated with each subsequent viewing of the photograph. The narrative that keeps the Sphinx and the Statue separate, one that suggests a linear time where antiquity precedes modernity, but modernity improves upon it through culture and technology, is also repeated with each subsequent copy of the photograph. Yet, as an instance of montage, the encounter continually retells multiple stories of imperialism that are differently inflected than Grigsby suggests. For example, she reads this chance meeting as an indication of the Statue of Liberty’s modern architectural genius, as a “demonstra[tion of] just how much 19th-century engineering ha[s] trumped ancient Egypt.”42 This echoes Trafton’s arguments in Egypt Land, that America sees its own empire as a reflection of Ancient Egypt’s grandeur with a progressive twist.43 Both Trafton and Grigsby offer a reading of imperialism which emphasizes the relationship between America and Egypt as one of appropriation and modification, where the latter always appears as improvement. This is because technology insists that while modern construction might look to the past for inspiration, contemporary production is ideologically and technologically superior.44

The Statue of Liberty provides a unique example of this type of revision, but its narrative is seldom recounted in American history. As Grigsby suggests, “the photograph of the Statue of Liberty and a replica of the Great Sphinx is not only not a product of photo montage, it evokes historical fact and can stand for a larger history.”45 The image recalls the forgotten origin of Lady Liberty, which was once intended to stand on the banks of the Suez Canal. Its sculptor, Frederic Auguste Bartholdi, inspired by the architecture of Egypt’s past, began drawing up the plans for an Arab peasant woman in the shape of a giant lighthouse dressed in flowing robes and sandaled feet. This monument would stand proudly at the entrance to the canal that the French had promised to build with the help of the Egyptians. It would be an homage to the enlightened system of commerce and comprehension that the French colonists’ waterway would deliver to Egypt. However, when economic situations stifled this exchange, Bartholdi was forced to scrap the project. Months later, on a trip through New York’s harbor, on his way to America, the sculptor imagined a new home for his Arab Peasant. The copper Lady in her renovated garb was transformed from a monument intended to celebrate French colonial enterprise in North Africa into the Statue of Liberty.46 With this move, the statue became a symbol of American freedom and an image of economic and ideological exchange in the modern age. The statue thus links French colonialism to American immigration, the concept of the American Dream, and the spread of global capital.

The encounter echoes this history and reevaluates New York’s claim on the modern, producing a reading of the Statue of Liberty as a copy, recycled from the Arab world’s distant past and made new by French colonialists in the American context. This narrative is reimagined through the meeting of the Sphinx and the Statue where discourse and history are revealed as nothing more than repeated stories. New York is transformed into a stage upon which clashing civilizations might struggle for control of the image. The harbor provides a setting for an “actual if unlikely event,” an appropriation of Ancient Egypt and its anachronistic displacement of dominant discourses.47 Moreover, it also invokes the colonial exploitation of Native Americans that led to the formation of the United States. The colonial projects in Egypt by the French and English were part of a European civilizing mission in non-European nations. While early American settlements are often distinguished from later European imperialism, both projects classified places like Egypt and the ‘New World’ as “‘no-man’s land’ or wilderness . . . characterized as resistant, harsh, and violent, a country of savage landscapes to be tamed; ‘shrew’ peoples (Native Americans, Africans, Arabs) to be domesticated; and desert to be made to bloom.”48 Standing as a symbol for American freedom, the advanced engineering of the Statue is a result of violence, exploitation, and seizure of lands; these neglected histories that made Euro-American domination possible are forced to live in the shadow of Lady Liberty’s light. However, as the Sphinx enters her domain, the North African colossus offers a reply and modernity’s claims to progress revealed as a one-sided story based on genocide, theft, and greed.

Perhaps this is why the Sphinx alongside the Statue appears like a digitally generated image to the contemporary viewer—in temporal and geographical terms, these figures do not belong in the same space, time, or episteme. However, they remind America that its own imperialism is borrowed from its view of an Egyptian past. The spectator may not be obtaining knowledge from a museum exhibit of mummies and papyri, but they are still forced to encounter conflicting narratives in the form of modern irony. At first glance, it appears as though an image of the Sphinx were superimposed onto a photo of the Statue, the former obscuring the latter’s base by passing on the side closest to the camera’s lens. Of course, the photograph’s frame is determined by the photographer’s position; if Abrams had been standing on the other side, the framing of the ancient and modern might have been very different, and the histories exposed read from an alternate perspective. Thus, the frame demonstrates that interpretation is often determined by place of reception, by the position of the reader more than by the facts that inform the event. Shot from another angle, the photograph might be read as a comedic gesture, one easily discarded as an absurd joke involving distant contemporary worlds.

However, present-day relations between the ‘Arab world’ and America increase the stakes of this image. The archived historical moment reimagines a geographical map that attends to unevenly distributed global networks that are often folded into stories of American progress and Egyptian stasis. The objects on display do not generate power, as Colla suggests about the artifacts exhibited at the British museum, where “the gallery space itself is static and designed to insulate objects from the ravages of history.” Instead, it is the museum’s “capacity to stop time, to preserve, [that] enables the presentation of objects as diachronic history.”49 The collision of the Sphinx and the Statue is similarly dynamic as an instance of photographic montage. The implied movement of the Sphinx and the immobility of the Statue demonstrates a process of reading history as synchronic, where time is not stopped even when it is frozen in the photograph, but instead is suspended—the dominant story interrupted by a moment of active and ongoing response. Twain’s meditation on the Sphinx’s gaze re-inserts itself into a cosmopolitan center, re-determined by its new surroundings. The copy, a necessity of commodity culture, mocks the American motto of freedom and justice for all by recalling a history that might never have happened if Bartholdi had built his lighthouse at Suez.

The encounter between the Sphinx and the Statue reenacts the well-worn conflict between the modern Euro-American self and its primitive Oriental Others; however, its conclusion is more ambiguous. In the photograph, Egypt’s past becomes the condition of possibility for New York and American modernity. The ancient artifact displaces the Statue’s meaning through historical revision and mobility. The occasion for this collision of monuments is predicated upon the global trafficking of antiquities, which is an economy that views Egyptian history as nothing more than a commodity to be consumed through Western productions. This phenomenon is encapsulated by the event that motivated the encounter: Verdi’s Italian opera, performed on an American stage. Aida is put on display and consumed in a manner similar to the Egyptian artifacts in European or American museums: they are held up as authentic relics or truthful narratives from the Ancient Orient. The image of the Sphinx and the Statue can certainly be viewed analogously. However, the sheer size of the monuments indexes the layers of neglected history. In Arab and American retellings, the Sphinx, the Pyramids, and the temples at Abu Simbel are often cited in contemporary accounts to mark a decline in the Arab-Islamic world. These colossi present evidence of a great civilization that has fallen into despair according to the narrative of modernity. In the West’s version, it is as though Egyptian greatness begins the narrative of progress, but then falls out of history.50 However, in the photograph, this loss is refused, and rather than reproduce this limited view of the past, the encounter employs elements of montage and allows history to speak itself through association. “The rags, the refuse,” the fragments of history that are often discarded, “come into their own” in this image by inciting a discourse that moves in several opposing directions at once.51

TWO ARABS IN NEW YORK: ARABIA IN “FRAGMENTS”

The meeting of the Sphinx and the Statue of Liberty is an unraveling of the dialectics between East/West and past/present. Its location in New York is fundamental to this undoing, for as I have discussed, it occurs in the waters crossed by millions of immigrants over decades of immigration to the United States. This outdated narrative of America’s promise to immigrants enhances the irony of its critique, as the encounter’s juxtaposition disrupts the myth of the American Dream. Shot through with imperial resonances, the Statue’s promise to protect the tired, poor, huddled masses of distant nations is also called into question.52 The Sphinx reenacts the romantic notion and the actual process of immigration on a colossal scale by passing through the Harbor with ease. However, this was not the experience of many who traveled to the United States during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including those from Arabic-speaking countries. In fact, in Strangers in the West, a history of Syrian immigration between 1880-1900, Linda Jacobs recounts a less-welcoming picture:

Americans regarded the new arrivals with both fascination and horror. The newspapers played an important role in stirring up American fear and loathing of these newcomers, while adoring (and exploiting) their exoticism. Early newspaper stories described them as indignant beggars who threatened to become a burden on American society. The immigration authorities were constantly threatening to send them back and often did so.53

Of course, many crossed the waters, formed communities, published newspapers, opened stores, peddled goods, and became naturalized citizens of the United States. Yet, as Jacobs suggests, Orientalist discourses were certainly present in the minds of Americans at the time, and these discourses had a dual effect on arriving emigres. On the one hand, the threat of non-admittance or of being sent home based on negative associations with Arab culture was real. On the other, many new arrivals employed the exotic image of their Ottoman roots in order to financially survive the early days of Syrian immigration and countless took to peddling Oriental goods to Americans and Arabs.54

Ameen Rihani was among the early Syrian emigres to America. Born in Freike, Mount Lebanon, Rihani’s immigration was largely successful. In Ottoman Syria, his family operated a raw silk factory, but like many other Syrio-Lebanese families at the time, they resettled in New York in 1888, just two years after the completion of the Statue of Liberty in New York. Oddly, it was the building of the Suez Canal that forced many silk farmers to move to the United States; when the waterway was finished, Europeans had a more direct route to cheaper silk from China and Japan. Consequently, the silk industry in Lebanon suffered.55

After his arrival in America, a young Rihani had his first encounter with regular schooling in English, and while his father hoped he would work in the family business, at an early age Rihani showed an interest in literature, art, philosophy, and politics.56 In his adult life, these interests would flourish, as Rihani became one of the most prolific Syrian intellectuals in America.57 His biography is interesting on its own, but I cite it here to situate the context in which Rihani was writing. He was a Christian from Lebanon who moved to the United States at the age of twelve. Rihani was an intellectual situated somewhere between Arab and American epistemologies, which was influential on his development as a scholar. As a result, many of his works focused on questions of Pan-Arabism, the Arab American experience, and the political situations at home in America and Lebanon, and also in Palestine, North Africa, and ‘Arabia.’ In fact, Nijmeh Hajjar notes in The Politics and Poetics of Ameen Rihani, that the early émigré’s interest in Pan-Arab movements motivated his desire to write an account of the Arabian Peninsula. Hajjar suggests, “apart from emotional and intellectual motives, [Rihani’s] travels aimed at serving the Arab cause, namely Pan-Arabia (al-wahda al ‘arabiyya).”58

Pan-Arabism was highly debated by Arab Americans during the time when Rihani wrote Arabian Peak.59 Just a few short decades after the first waves of Arabs began migrating to the United States, the country passed the National Origins Act of 1924, limiting the number of emigres to America by country of origin. Syrians were limited to around 100 new entrants per year, a decision that was largely based on questions of race and “desirability” of the immigrants in question.60 Arab American communities responded to this legislation with discussions about the importance of Syrian production to civilization, a move, perhaps, to convince United States lawmakers that Syrians were a welcome addition to the country. Since Syrians constituted the largest number of Arabs in the United States, this method of persuasion carried significant weight for those already in the country as well as for those who were on their way.61 Examples of these attempts can be found in The Syrian World, a weekly, English-language journal from New York, first published in 1926. To illustrate, in August 1927, Syrian scholar Philp Hitti writes, “not only were the people of Syria the first. . . in Western Asia to join the procession of modern progress but in the last century and a quarter they have achieved more genuine progress, perhaps, than any other people in that whole region.”62 Hitti’s argument not only sings the praises of the Syrian people, but it also situates them in relation to other, perhaps less-modernized inhabitants from the broader “Oriental” regions.

In the years following, arguments such as these took on a more specific target: other Arabs. As the political climate continued to circulate around discussions over race and “desirability”63 of Arab immigrants to America, Hitti published another piece in The Syrian World, but this time, he asked a more direct question: “Are the Lebanese Arabs?” In this article, where Lebanese and Syrian are used interchangeably, Hitti outlines what he sees as the merits of Syrians based on their race or contribution to civilization, while demonstrating that their relationship to the Arabs of Arabia is namely linguistic. He claims that the term “Arab” more specifically refers to those “of the Arabian Peninsula who entered Syria at the time of the Islamic invasion about the middle of the seventeenth century.”64 While he lauds the language they share, he insists that the invasion was unfortunate, suggesting that the Syrians are distinct from the Arabs in cultural, religious, and philosophical practices. This is not to suggest that Hitti meant to situate Arabs and Syrians as separate and unequal, but merely to demonstrate that the project of Pan-Arabism was not agreeable to all Arabic speakers and intellectuals of the day. Hitti and Rihani were both major contributors to The Syrian World, and their works were in direct conversation. The tension surrounding questions of Arab-ness and Syrianness were clearly on Rihani’s mind as he set out on his journey to Arabia.65

While Rihani’s immigration and life in “the Syrian Colony” certainly mark an important historical moment in the story of Arab immigration to the United States, his role as an intellectual and activist with a focus on PanArabism is perhaps more significant.66 Yemen and the Arabian Peninsula were geopolitically noteworthy areas during the interwar period and after the fall of the Ottomans. Even before the discovery of oil in the 1930s, these areas were of interest to the British and the Americans largely due to coffee production and the Peninsula’s strategic location on the Persian Gulf.67 Rihani’s text is concerned with how politics in the region are represented within the United States, as he spends much of the travelogue trying to connect with Imam Yahya, Yemen’s ruler at the time. After meeting Yahya in the second part of the narrative, Rihani’s main objective is to describe the everyday workings and political system of the Arabian leader. In a sense, Rihani serves as a self-elected cultural ambassador, a translator of the Arabian Peninsula into the languages that Americans and Arabs might both understand.68 Rihani’s desire, to create a theoretical and political framework that might unite speakers of Arabic from Syria to Yemen as well as those living in diaspora, is an important move in this moment of Yemen’s history, a country that would later become isolated due to colonial interventions and the discovery of oil in the region.

While Arabian Peak is an attempt at writing an ‘objective’ account of the people and lands he encounters, Rihani is not always successful at presenting an unbiased critique. This is evident even in the opening lines of his travelogue, as Rihani’s engagement with the Arabs of Arabia is mediated by his linguistic and cultural immersion in America. To reiterate, Arabian Peak begins in the “office of an Arabic newspaper in New York,” but namely details Rihani’s travels through “the Yaman,” which includes modern-day Yemen and the Arabian Peninsula.69 In the text, Rihani depicts himself, an Arab with an American passport “adding something to [his] little store of knowledge” by traveling to a place that is seemingly unknown. Much of Arabian Peak is determined by the initial encounter between Rihani and the “man from the Yaman,”“even though we never see the man again. However, the inclusion of the anecdote shows an archive of knowledge that begins even before Rihani’s departure. Presented simultaneously, the conversation with the man and Rihani’s desire for knowledge signify a congruity between the two: knowledge is translated from Arabic and is generated from “the Yaman” through the figure of the man.

Like the encounter between the Sphinx and the Statue, Rihani’s brief conference with the Yemeni stranger brings together myriad places. The text passes through New York, America, Arabia, the Syrian Colony, and Yemen; it collects these disparate locations and histories into one synchronous point that is predicated on the global reach of the book and the local readership of the unnamed newspaper.70 Considering the crossover of both publications, each provides a compendium of readers that register and “store” a little knowledge of their own. Additionally, the encounter is constituted by the past and present of the spaces it traverses and positioned as always looking toward the unknown. As a result, the text reads as history in the making and the encounter builds on what came before. Rihani’s story, already on the “eve of departure,” is an example of montage as a dynamic restating of the past and present of the nations, cities, and regions it accumulates. The result is an archive, a depository for understanding the ‘Arab world’ and America by reading them together.71

In Rihani’s Arabian Peak, the juxtaposition of two Arabs in America—one from Yemen and one from Syria—acts as a reply to the dominance of progressive modernity. Rihani relates the encounter as a refusal to histories that favor Western hegemony over epistemology and temporality, which is emphasized by his request for knowledge from the foreigner. As Jacob Berman suggests, the encounter is “p]ositioned within the ‘Syrian Colony of New York’ and with access to its mode of modern print culture, the Lebanese emigre author nevertheless seeks ‘knowledge’ from a provincial Arabian stranger before setting out on his Oriental tour.”72 The narrative itself depends upon the appearance of the “man from the Yaman,” an encounter that immediately precedes Rihani’s departure for Arabia. The request for knowledge creates a hesitation in the text, a pause that cannot be recuperated through linguistic or spatial similarities. Here, the man’s knowledge is the condition of possibility for the travelogue to be written, and the encounter in the office is dependent on movements from Arabia to New York, rather than the other way around. Yet, Rihani’s intimacy with the man is also observed in the gap: it suspends his departure as the characters and the reader pass through the numerous places that are inscribed onto this brief conversation. The two never meet again, but their chance meeting frames all the encounters that follow, whether they are with British traders on the road, great Emirs in the desert, soldiers in Sana’a, or the Arabian leader, Imam Yahya. The interaction with the man constructs the borders of the total image represented by the text, one that links New York, America, Arabia, the Syrian Colony, “the Yaman,” and the world, into a singular and synchronic moment.

When Rihani meets “the man from the Yaman,” he notes a comparison between himself and the stranger and employs a methodical response. The first difference Rihani notices is rooted in place, as his interlocutor’s “soft unfamiliar accent” marks him and his Arabic as outside the modern space of the newspaper office. It frames the dialectic between modern print culture and “the Yaman,” self and Other, Arab and American, while simultaneously referencing a distinction between the Arab and the Arab American. Rihani positions himself as belonging in America, or at the very least in the “Syrian Colony,” but the man does not seem to belong. Even though we only witness his existence in the office, he is situated as one who is “seldom” found in such a locale.73

The presentation of the anecdote indicates that pieces of the conversation are left untranscribed, for at some point the man speaks in his “soft unfamiliar accent” to tell Rihani that he hails from “the Yaman.” However, this moment appears to have occurred before the text begins, because the man’s origin is relayed to the reader through Rihani’s narration only. When the man does speak for himself, the text marks him as a different kind of Arab through the dialogue that ensues. The narrator poses a series of questions, but the answers appear to reassert dominant readings of Arab lands and people as wild and savage, in need of modernization and cultivation. Rihani begins:

“Are there any foreigners in Al-Yaman?”

“No, no. The foreigners are not permitted to live in Al-Yaman.”

“Are they allowed to travel?”

“No, no.”

“And should a traveller come?”

“Wallah, we’ll slay him.”

“Suppose he travels in disguise.”

“If we know him, wallah, we’ll slay him.”

“Do you permit Syrians, who are Arabs like yourselves, to travel in your country?”

“If they are Christians, they and the foreigners are one in the eye of the people of Al-Yaman. Their speech alone might protect them.”

“And if a Christian traveller’s identity is discovered?”

(In the same unchanging mellifluous accent) “Wallah, we’ll slay him.”74

The pattern of their conversation continually comes back to the refrain “Wallah, we’ll slay him,” which suggests that the narrator is embarking on a mission that can only end in death. However, the reader is left to assume that the author survives the trip, at least long enough to write all 293 pages of the book. At first glance, the repetition of this phrase appears to confirm American beliefs about the “unchanging mellifluous” barbarism in Arabia. Every inquiry leads to the same conclusion: if outsiders travel to Yemen, they will likely be “slain.” The region, like the man, is positioned outside of a modern capitalist schema, because it does not fit into an economy that values free trade and travel of people, commodities, and knowledge across international borders. Instead, Rihani, the foreigner in this instance, is advised to avoid any travel.

But Rihani’s journey does not end in death and the reader has material proof of this: Arabian Peak. This opening, then, suggests that the author occupies a privileged position: he, and perhaps even the man, both appear as figures that can move between the competing economies and epistemologies of Arabia and America. Though, his depiction also threatens his larger mission: if the text is read with dominant assumptions about Arabia in tow, then his encounter works to confirm the barbarity of the people from this region, which might undermine his commitment to Pan-Arabism among other Syrian Americans.75

However, the echo, “Wallah, we’ll slay him,” sets a poetic rhythm for the prose and provides a comedic effect. The moment is playful, which is emphasized by Rihani’s suggestion that the line is delivered in the “same unchanging mellifluous” speech. The modifiers “same” and “unchanging” create the character’s affect: he is calm and collected and even seems to have a sense of humor about the negative stereotypes of his countrymen. The text is not asserting a truth about the man, or “the Yaman,” but merely laying out a structure through which the narrative will emerge, one of reply to dominant representations of Arabia. Moreover, by leaving “wallah” untranslated, even though it simply means ‘by God’ and is used to express sincerity by the speaker, the text restricts access to its English reader. On the surface, the move suggests that there is no equivalent meaning in English of the idiomatic Arabic phrase, but it also denies the English reader command over the exchange. The untranslated Arabic demonstrates knowledge that is incomprehensible to nonArabs. If “wallah” remains in the text as Arabic transliterated into Latin script, then the man is not an object for American consumption, but an Arab with a past constituted by multiple synchronous histories.

It is notable that Rihani only reproduces this aspect of the dialogue directly, because its absurdity paints the “knowledge” Rihani obtains as mere banter. Perhaps the timeliness of the anecdote is an ironic metaphor meant to recreate the image of an American traveler about to set out on an unknown journey to uncover the secrets and mysteries of a foreign land. However, even before his departure, the traveler is aware that his experience and perceptions will inflect any chance of ‘objective’ knowledge. To echo Berman, in this encounter “Arab-ness is presented as a performative modality, rather than an essential identity.”76 It is not something to be discovered, it is not out there to be found, but it is located in the presentation of oneself as an Arab in the world in relation to other Arabs. Berman considers “Rihani’s self-identification [as] simultaneously [that of] a colonist and an immigrant, a native and a foreigner, an Orientalist traveler and an Oriental,”77 at once a translator and that which is translated. Rihani’s first-person travelogue begins in the modern American city, continues on to the Peninsula, and ends with all the histories in-between, somewhere outside the dominant trajectory of Western progress.

Arabian Peak is full of insight and bias and Rihani is quite aware of his own position as Orientalist ethnographer. However, he is also firmly committed to a unified Arab region. The inclusion of the Yemeni at the text’s opening, whether farcical or truthful, proposes a critique that speaks between the lines and untranslatable moments and makes the reader’s own embedded notions about the Arab world visible. The encounter is positioned as a narrative frame that returns in different forms, though we never see “the man from the Yaman” again. His arrival announces an alternative entrance into the text-it denies the English reader access to an “objective” account of the Arabian Peninsula and foregrounds the movements between and within Arab, American, and Arab American ways of knowing. Rihani’s meeting with the man imagines a mode of reading that engages with the complexities of the present and past in Yemen and in America while it displaces dominant representations of these narratives.

Like the encounter between the Sphinx and the Statue, Rihani’s dialogue recalls a history “seldom” registered, that of “the Syrian Colony of New York.” However timely the man’s arrival might be, the text situates this moment as an arrangement of several real places in one simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar place. Everyone knows New York City, but less known is the booming Syrian community that settled in lower Manhattan at the turn of the twentieth century. For the contemporary reader, the encounter reproduces this forgotten history. It suspends this moment from the travel account, as it is the only encounter that occurs in America before the trip commences. It is significant that it takes place in the “Syrian Colony of New York,” as it archives the significance this space within the histories of Arabia, America, Lebanon, Ottoman Syria, and local and global economies. It forms a moment of Arab unification that occurs far from the lands Rihani wishes to unite by creating a referent for a community of Arabs living together in a foreign space. The “Syrian Colony,” known as Little Syria was “the commercial center for Arab Americans . . . [Its stores] imported food, kitchen utensils, water pipes, and cultural items such as musical instruments, from back home for the comfort of their fellow villagers residing throughout the United States.”78 The community was a bustling downtown for Arab American life, which included newspapers in Arabic and English, Arab-run banks and stores, and Syrian neighborhood societies and schools. The residents in lower Manhattan even had structures in place to help new immigrants find their footing in the new country.79

Today, the Syrian Colony is gone, but its specter lives in the shadow of New York’s contemporary financial district. It survives in photos and archives, but also in texts like Rihani’s, that situate it as a period of note and a space of unexpected encounter. By creating a citation in the text for the “Colony” and the “Arabic newspaper,” Rihani situates himself and his relation to Arabia into the uneven frame of Arabian Peak Berman suggests that Rihani presents “himself as a local Arab colonist in America, and a cosmopolitan American stranger in Arabia, [and as a result] Rihani troubles any stable notion of center and margin.”80 The man destabilizes the “notion of center and margin,” but also locates a moment of reply to Syrians that distinguish themselves from other Arabs: the man is a stranger in the modern urban space of New York and in the “Syrian Colony” as well, among other Arabs.

However, by keeping the man’s arrival and business shrouded in mystery, the text refuses the tendency to imbue the Other with a meaning that is based on appearance and assumption. Similarly, by declining to provide a context for the “Syrian Colony,” the text maintains its singularity and impact in the city of New York. As Berman suggests, this early moment in Arabian Peak takes a singular space and time—the office in present-day New York—and transforms it into a multiplicity of local, national, and transnational migrations where knowledge travels against the modern current, from Yemen to New York, and from the Syrian Colony to the Peninsula. The image of world here is not based on models of center and periphery, but a frame within which Arabia and New York can be repositioned together. When written and circulated, this alternative history challenges the notion that knowledge is tied to a particular space and counters the reification of thought produced at a particular time. Instead, it demonstrates the text’s globality and multiplicity. The man’s arrival is as unexpected as the Sphinx in New York Harbor, but his inclusion in New York, before Rihani’s departure, restates the claim that knowledge does not move uni-directionally.

CONCLUSION

In her work, Epic Encounters, Melani McAlister examines the theoretical and political implications of the fraught “encounter” between America and the Middle East in contemporary history. She determines that “the postwar significance of the Middle East for Americans coalesced as part of the process of constructing a cognitive map suitable for the new ‘American Century.’”81 In other words, in the postwar era a relationship between these two broadly defined places was codified, making the modern Middle East a necessary Other for Americanization on a global scale. The “cognitive map” moves and is reshaped by each moment in the contemporary history of the United States and the broadly defined Middle East. McAlister’s book attempts to counter essentialisms that are generated in the media by pointing out that “the Middle East has been both strategically important and metaphorically central in the construction of US global power.”82 This is based on ideas that “are deeply historical and highly contested products, forged at the nexus of state power, cultural productions, and sedimented presumptions.”83 Through appropriation and epistemological stasis, the United States has risen to global power, in part, because of its encounter with the Middle East. The relation between these two spaces is one that maintains US power and continually represents the Middle East as backward and barbaric, a place to be regulated through international policy and cultural production.

To borrow from McAlister, the Sphinx with the Statue, and Rihani alongside the man, produce instances of “epic encounter,” recalled in the origins, histories, presumptions, and discourses that surround each figure and monument. Whether these moments are read as cultural appropriation, reproduction of Orientalist discourses, or digitally enhanced kitsch, they are rooted in “deeply historical” debates over power and knowledge. McAlister’s argument suggests an epistemological shift, a reading of “encounter” that takes the political and economic situations of modern, capitalist production into the realm of cultural analysis. The images produced by culture are “encounters . . . that happen across wide geographic spaces, among people who will never meet except through the medium of culture.”84 The task of the critic is to locate these intersections, track their circulation, and re-determine their meaning in, and in response to, the ‘American century.’ These encounters make room for the Arab American in this history.

I began this paper with an epigraph from Walter Benjamin’s unfinished Arcades Project to posit a method of reading literary and visual encounter as a project of montage. These moments, imagined as literary and visual multiplicities locate history in the “rags” and the “refuse”85 in the forgotten and discredited narratives that often conflict with teleological notions of the modern world. However, they present rich and varied meanings that make use of these fragments, to “merely show” another side of the story.

NOTES

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 460.↩︎

Found in Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Colossal: Engineering the Suez Canal, Statue of Liberty, Eiffel Tower, and the Panama Canal (Pittsburgh: Periscope Publishing, Ltd., 2012), 8. (Licensing for the photograph through © Bettmann/CORBIS.)↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ameen Rihani, Arabian Peak and Desert: Travels in Al-Yam an (New York: Houghton Mifflin Co, 1930), 1.↩︎

Arabian Peak and Desert is part of Rihani’s trilogy, which details his travels in the Arabian Peninsula in the early to mid-1920s. In each volume, he produces accounts of his meetings with Arab rulers: in Arabian Peak, he is focused on his encounters with Imam Yahya of Yemen. In Arabic, his accounts were published with different titles: Muliik al-’Arab, Volumes 1 and 2 (Beirut: Dar al-Rihani, 1960). [first published in 1926]; Tarikh Najd wa Mulhaqatih (Beirut: Dar al-Rihani, 1964). [first published in 1927]. For references and context, see Arab Civilizations Challenges and Responses: Studies in Honor of Constantine K. Zurayk, eds. George N. Atiyeh and Ibrahim M. Oweiss (New York: State University of New York Press, 1988), 239; “Al-Rihani, Ameen (1876–1940) Arab American Writer and Traveler.” Literature of Travel and Exploration: An Encyclopedia, ed. Jennifer Speake (New York: Routledge, 2013); and Nijmeh Hajjar, The Politics and Poetics of Ameen Rihani: The Humanist Ideology of an Arab-American Intellectual and Activist (London: LB. Tauris Publishers, 2010), 52–53.↩︎

Hajjar, The Politics and Poetics of Ameen Rihani, 21.↩︎

Benjamin, Arcades, 460.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Sergei Eisenstein, “The Montage of Film Attractions,” Defining Cinema, ed. Peter Lehman (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutger’s University Press, 1997) 18.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Benjamin, Arcades, 460. (For all quoted text in this paragraph, please refer to the epigraph.)↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Eisenstein, “The Montage of Film Attractions,” 18.↩︎

Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), 321.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

It is also useful to consider Said’s own revisions to “Orientalism” through his discussion of power relations and cultural production in Culture and Imperialism, as one example. He argues that the West’s hegemonic relationship with once-colonized (through settlement and military occupation) parts of the world was, and is maintained through the creation of categories and chronologies that favor an almost monolithic notion of the West as technologically and culturally superior. Said suggests that “those categories [which] presum[e] that the West and its culture are largely independent of other cultures, and of the worldly pursuits of power, authority, privilege, and dominance” are ideas that sustain and reproduce Western empires. Colonial and neo-colonial histories are built on imperial interests and rooted in the notion that the West is “stable and impermeable.” In this work, he reframes his discussion of Orientalist discourses in relation to cultural production as a project of unthinking the embeddedness of Eurocentrism in aesthetic practice. See Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage, 1993), 111.↩︎

Lisa Lowe, Critical Terrains: French and British Orientalisms (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991), ix.↩︎

Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media (London: Routledge, 1994).↩︎

Shohat and Stam, Unthinking Eurocentrism, 1–2.↩︎

“Reply” is cited from the encounter between Rihani and the Yemeni man (Arabian Peak, 1). I use it throughout as shorthand for the major argument in this piece, which suggests that through montage these singular moments offer differently inflected accounts of history and epistemology than those provided by Western-centric narratives of progress, which often exclude postcolonial spaces like the Middle East and North Africa.↩︎

Mark Twain, The Innocents Abroad or The New Pilgrim’s Progress, ed. Shelley Fisher Fishkin (New York: Oxford UP, 1996), 628–29.↩︎

Scott Trafton, Egypt Land: Race and Nineteenth-Century American Egyptomania (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), 12.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Grigsby, Colossal, 8.↩︎

For more on the specifics of colonial forces in Egypt as well as Egyptology and Egyptomania as a significant part of imperial projects there, see Elliot Colla’s Conflicted Antiquities (note 34); Trafton’s Egypt Land (note 29); Said’s Culture and Imperialism (note 23); and Timothy Mitchell, Colonizing Egypt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991).↩︎

See Trafton, Mitchell, and Colla (note 32) for more on the appropriation of Egyptian iconography and what it comes to represent in the history of colonialism and cultural imperialism.↩︎

Elliot Colla, Conflicted Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 4.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Shohat and Stam, Unthinking Eurocentrism, 154.↩︎

See Colla’s “Introduction” to Conflicted Antiquities; Mitchell’s “Introduction” to Colonizing Egypt (note 32).↩︎

Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism, 111–32; Timothy Mitchell, Colonizing Egypt, 17.↩︎

Said, Culture and Imperialism, 112.↩︎

Kate Rix, “Art on a Very Big Scale,” last updated 15 November 2010, http://ls.berkeley.edu/?q=arts-ideas/archive/art-very-big-scale.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Trafton, Egypt Land, 2.↩︎

See Trafton’s discussion of Egyptian iconography and American empire in the introduction to Egypt Land, 3–10.↩︎

Grigsby, Colossal, 8.↩︎

Ibid., 8–9.↩︎

Ibid., 8.↩︎

Shohat and Stam, Unthinking Eurocentrism, 143.↩︎

Colla, Conflicted Antiquities, 6.↩︎

For example, Mitchell discusses this in his work Colonizing Egypt (note 32) as an idea held by Arabs and Europeans alike. Paraphrasing the writing of Frenchman Due d’Harcourt, Mitchell cites colonial accounts: “The backwardness of the Egyptians, Harcourt had said, was due to certain mental traits that no administrative reforms by the British could ever noticeably alter. These included a submissive character, an insensibility to pain, a habit of dishonesty, and above all an intellectual lethargy that had rendered all Oriental societies immobile, unable to undergo any real historical or political transformation. The ideas, customs, and laws of the Arabs today were just as they had been one thousand years before,” Colonizing Egypt, 112.↩︎

Benjamin, Arcades, 460.↩︎

See Emma Lazarus’ poem, “The New Colossus,” engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty, from which this phrase was extracted.↩︎

Linda K. Jacobs, Strangers in the West: The Syrian Colony of New York City, 1880–1900 (New York: Kalimah Press, 2015), 34.↩︎

See, for example, Chapter 5, “The Role of the World’s Fairs: From Peddler to Capitalist,” and Chapter 6, “Peddlers,” from Jacobs, Strangers in the West (note 53).↩︎

Elsa Marston Harik, The Lebanese in America (Minneapolis, MN: Lerner Publishing Co, 1987), 19.↩︎

Hajjar, The Politics and Poetics of Ameen Rihani, 25.↩︎

See Wail Hassan, “The Rise of Arab-American Literature: Orientalism and Cultural Translation in the Work of Ameen Rihani,” American Literary History 20 (2008): 245–75.↩︎

Hajjar, Politics and Poetics, 195.↩︎

For example, see Philip K. Hitti (notes 62 and 64).↩︎

Sarah Gualtieri, Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 79.↩︎

Jacobs, “Introduction” and Chapter 2, “Syrian Immigration to New York,” Strangers in the West.↩︎

Philip K. Hitti, “Syrian Leadership In Arabic Affairs,” The Syrian World, II, no. 2 (August 1927), 3. Box 145, Faris and Yamna Naff Collection, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Washington, DC, 2016.↩︎

Many works in Arab American studies have focused on the questions of race and identity in relation to desirability of those immigrating to the US. For more on how race is specifically linked to Arab immigration in the past and present, see Gualtieri (note 58); Jacobs (note 51); and Race and Arab Americans Before and After 9/11: From Invisible Citizens to Visible Subjects, eds. Amaney J. Jamal and Nadine Christine Naber (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2008).↩︎

Philip K. Hitti, “Are the Lebanese Arabs?” The Syrian World, V, no. 6 (February 1931), 6. Box 145, Faris and Yamna Naff Collection, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Washington, DC, 2016.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Rihani, Arabian Peak, I.↩︎

Ahmed Noman Almadhagi, “Introduction,” Yemen and the USA.: A Super-Power and a Small-State Relationship, 1962–1994 (London: Tauris Academic Studies, 1996).↩︎

To reiterate, he wrote of his experiences in Arabia in Arabic and then English-the former published in Beirut in 1926–1927, and the latter published in the States in 1930–1931.↩︎

For the quotations in the next few pages, unless otherwise noted, please revisit Rihani’s encounter with the Yemeni man. I will try to avoid repeated citations throughout the close reading of Rihani’s opening lines. Additionally, I will refer to Yemen in its present-day transliteration, rather than with Rihani’s spelling, “Yaman.” However, when quoting directly to maintain the original form or offer close reading of his text, I will use Rihani’s spelling. In these instances, “Yaman” will always be placed inside quotation marks. Rihani, Arabian Peak, I.↩︎

By the late 1920s, there were many Arabic newspapers published in New York City. Their numbers were declining, though, as second-generation Arabs in America were speaking and reading far less Arabic than the previous generation. For more on this, it is worth looking at some of the fantastic research done about these newspapers. See Alixa Naff, Becoming American: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985); Fayhad Abdullah Tayash and Kenneth Kahtan Ayouby, “Arab-American Media: Past and Present,” The Arabic Language in America, ed. Aleya Rouchdy (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1992), 162–83.↩︎

Rihani, Arabian Peak, I.↩︎

Jacob Berman, “Mahjar Legacies: A Reinterpretation,” Between the Middle East and the Americas, ed. Evelyn Alsultany and Ella Shohat (Ann Arbor: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 65.↩︎

Rihani, Arabian Peak, I.↩︎

Ibid., 1–2.↩︎

See note 64.↩︎

Berman, “Mahjar Legacies,” 75.↩︎

Ibid., 67.↩︎

Randa A. Kayyali, The Arab Americans (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006), 36.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Berman, “Mahjar Legacies,” 65.↩︎

Melani McAlister, Epic Encounters (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005), 4.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid., 4–5.↩︎

Ibid., 1.↩︎

Benjamin, Arcades, 460.↩︎