Edward E. Curtis IV & Lindsey Waldenberg

DISCOVERING ARAB INDIANAPOLIS: AN INTERVIEW WITH EDWARD E. CURTIS IV

Abstract

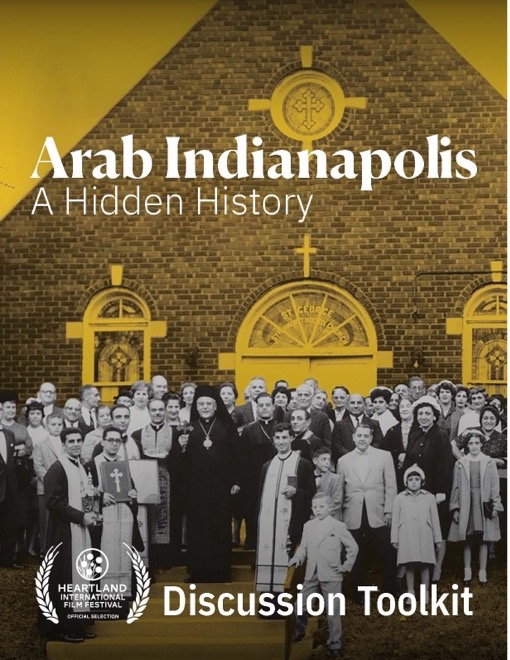

In Arab Indianapolis: A Hidden History, author and historian

Edward E. Curtis IV explores the origins and growth of the Arab American

community in Indianapolis, Indiana. The documentary spans 120 years of

history and discusses the city’s first Arabic-speaking neighborhood on

Willard Street, important community anchors such as St. George

Antiochian Orthodox Church of Indianapolis, and stories of trailblazing

individuals whose contributions expanded Arab American representation

and opportunities in Greater Indianapolis and beyond. The documentary,

which premiered in 2022, is part of a larger project that began as a

blog in March 2020. Since then, the “Arab Indianapolis” project has

launched a book, developed K-12 lesson plans, hosted educator workshops,

and, most recently, dedicated the city’s first memorial marker

celebrating the city’s Arab American history. To watch Arab

Indianapolis: A Hidden History and explore other facets of the

project, visit www.arabindianapolis.com.

ملخّص

في كتاب "مدينة إنديانابوليس العربية: تاريخ مخفي"، يستكشف المؤلف والمؤرخ إدوارد إي.كيرتس (الرابع) أصول ونمو المجتمع العربي الأمريكي في مدينة إنديانابوليس، عاصمة ولاية إنديانا. يغطي الفيلم الوثائقي ١٢٠ عامًا ويسرد تاريخ أول حي قطنه الناطقين باللغة العربية في المدينة والواقع في شارع ويلارد، وتاريخ مؤسسات مهمة مثل كنيسة القديس جورج الأنطاكية الأرثوذكسية، وقصص الأفراد الرائدين الذين أدت مساهماتهم إلى توسيع التمثيل العربي الأمريكي والفرص في مدينة إنديانابوليس ونواحيها. هذا الفيلم الوثائقي، الذي تم عرضه لأول مرة في عام ٢٠٢٢ هو جزء من مشروع أكبر بدأ كمدونة في آذار/مارس ٢٠٢٠. ومنذ ذلك الحين، لقد أطلق مشروع "إنديانابوليس العربية" كتابًا، وقام بتطوير خطط دروس لطلاب المدارس، واستضاف ورش عمل للمعلمين، ومؤخرًا، تم تخصيص أول علامة تذكارية في المدينة للاحتفال بتاريخ المدينة العربي الأمريكي. لمشاهدة "إنديانابوليس العربية: تاريخ مخفي" ….www.arabindianapolis.com واستكشاف الجوانب الأخرى للمشروع، تفضل بزيارة

Lindsey Waldenberg (LW): Thank you for talking with us today. To begin, from my understanding, this documentary is very much part a larger public history project. What inspired you to begin Arab Indianapolis? Could you share the story of where the seeds of that developed?

Edward E. Curtis IV (EC): A change in the way in which I did research was essential to how I became interested in Arab Indianapolis. Because I got my doctorate in the year 2000, I was late to the digital revolution in historical research. I was trained as an analog researcher in the 1990s and I never really had time to catch up to the revolutionary changes in digital research. But in the second decade of the twenty-first century, I finally did.

One of my colleagues, an urban archeologist, Paul Mullins, oriented me to the richness of the digital sources available in US urban history, including Sanborn insurance maps, city directories, digital versions of the census—the kinds of things you find in various databases, including Ancestry.com. And those sources became important to my writing of Muslims of the Heartland: How Syrian Immigrants Made a Home in the American Midwest. That book, which sought to document the everyday lives of the first two generations of Arabic-speaking Syrian and Lebanese Muslim Americans in the Midwest, relied primarily on oral histories collected not just at the Naff collection in Washington, DC, but also throughout various local and state libraries and archive collections.

Those oral histories give us a sense of how people felt, but it was just as important to depict the local and state contexts in which they were living. I used all these new—what were new to me—digital resources to depict their lives in unprecedented detail. And I discovered so much about the people about whom I had been hearing my entire life, because I too trace my roots to the Syrian-Lebanese migrations before World War I. One of the things that deeply inspired me was to think of these migrants as “locals” and as making homes wherever they went, even if those homes were temporary or terrorizing.

This echoed my own experience and my own attachment to the Midwest and my family’s five-generation attachment to the Midwest as Arab Americans. That kind of orientation to Arabic-speaking Syrian and Lebanese people inspired me to look much more locally and say, “Surely I can use the same kinds of sources that I’ve been using to depict in great detail the lives of Arabic-speaking Muslims in the upper Midwest.” I only had to scratch the surface to immediately see that there was this rich history of Syrian and Lebanese people which had been ignored or forgotten by everybody. It had been forgotten by historians of the state of Indiana. It had been forgotten by local historians. And it had never been picked up by Arab American Studies scholars. Indianapolis just wasn’t on the map of Arab America, even though, as it turns out, it has been a very important city to the history of Arabs in the United States.

My very modest goal in starting Arab Indianapolis was to link up with our local Arab American communities and begin to create oral histories as well as physical and digital archives of ephemera and other documents to write the history of Arabs in Indianapolis. Rather than creating a traditional archive, I wanted to create a digital archive and a website. For ease of use, we decided to use the StoryCorps app for people where members of the community could interview one another about their own memories and thus create this archive. That was all I intended to do at the very beginning.

LW: Clearly this effort had a snowball effect. So, you wanted Arab Indianapolis to begin mostly as a digital archive with community-driven oral histories with StoryCorps. How did you end up from starting with solely a digital presence to this film and other products?

EC: From the initial thought, I immediately consulted with members of my community who I knew or with whom I had been working for some time. I consulted with them as what I understood to be a community-engaged scholar, which to me means I’m not the only person who determines what a research project is, what will be explored in that research project, and what products the research will result in. I wanted to make history with the community—my community, the Arab Americans in Indianapolis. And so, I turned immediately both to institutions and to people. And I said, “Here’s my idea. What do you think about it? Would you support it? What should it look like to you?”

First of all, I got some institutional buy-in. I turned to organizations in which Arabs were represented, including the Indiana Muslim Advocacy Network, the Catholic Charities Immigrant and Refugee Services, local mosques, and the Syrian Orthodox Antiochian Church here. The other major development was that Hiba Al-Alami, the former executive director of the Indiana Muslim Advocacy Network, graciously volunteered to create a WhatsApp group of informal community advisors who gave their concrete feedback and expressed willingness to raise money for the project.

We officially began working on the website at the beginning of 2020, but then the Covid-19 pandemic happened. In fact, the first blog post on arabindianapolis.com came out very close to the initial declaration of emergency in March. Now this did more than throw a wrench into the research. None of the people on my WhatsApp group or anywhere else really wanted to record in oral history or an interview on StoryCorps.

LW: Why do you think that was the case?

EC: I think, in retrospect, they were far too busy with far too many important things to be doing this. And second, that’s asking for quite a lot of commitment from a project that hasn’t shown any results. And one of the conclusions I came to eventually is sometimes you must do things for the community before you can do things with the community. You’re asking them to commit their time, talent, and resources to something. You’ve got to show them that you’re serious and that you’re able. And so that’s exactly what we did. I pivoted very quickly, and we began to focus on the ancestors. And one of the first things we discover was that there was an Arabic speaking neighborhood in Indianapolis. Again, everyone’s either forgotten about this or no one ever knew it.

LW: How did you discover this? Was there one piece of evidence or did you put the pieces together by looking at the Sanborn maps or newspapers?

EC: It was the newspapers. They said, “There’s a Syrian quarter here, and there are hundreds and hundreds of people living on one street called Willard Street.” Well, there’s an added twist to the story. Willard Street, which no longer exists, was located on the land on which Lucas Oil Stadium, the home of the NFL’s Indianapolis Colts now. This is a story that speaks to displacement and renewal. This sort of recovery project began to get people’s attention. And with the help of my student researchers, I began to try as much as possible to reconstruct life on Willard.

It turned out that like Little Syria in New York, as Linda Jacobs has noted, many of the people who lived on Willard Street did not pass along the memories of living there because life was so difficult. When I was talking to their descendants, they did not know that their ancestors had lived on Willard Street, even though I could trace back through city directories and census data. We began to make more and more discoveries about the lost history of Arab Indianapolis. And more of our community members really started becoming more active on the WhatsApp group and started granting us interviews.

LW: I see. Essentially, once you had some product or a big development, people became more eager to participate because they saw that this project is moving forward and resulting in new discoveries.

EC: It’s a snowball effect, for sure. At this point, we’re cooking. We had too many stories that we can possibly tell. We began considering making a movie. I asked my advisors, “What do you think about this? This is going to be much bigger than anything we had planned in terms of money and time. Do you think it’s worthwhile?” They said yes, because this would put us on the public map in a way that a book or a blog would not.

LW: Yes, I would imagine that a film grabs a completely different audience who may be casually flipping through the channels, stumble on the film, and decide to watch it. And this speaks to one of the questions I have. You said this is your first film. How would you evaluate a film as doing public history as a public history project?

EC: I really enjoyed it. A lot of the documentary features me interviewing members of the community, talking not just about their history, but about the history of our ancestors and asking them to reflect on what that means to them. The reason I did that was because I was trying to weave together our past and our present, to create a sense of belonging not to some theoretical idea of our community or our nation, but instead to an actual real place with people and with real bonds that go back into the past. Not just looking at the present but rather weaving that together with what we’ve been doing for more than 100 years creates a sense of confidence and connection. When you talk to people and ask them to reflect on their past in front of a camera, and you take them back to a certain time and place, something magical happens in being there with them.

But let me get back to making the movie. I had never written a movie before. How do I do this? I turned to Graham Judd, with whom I had worked on a forthcoming documentary called American Muslims: A History Revealed, which came out on PBS in fall 2024. He mentored me in how to write a shooting script. And he was the one who suggested that given the different stories that I was likely going to tell, I would need to be the host and community member tying it all together. While this set-up is a more traditional, and some would say old-fashioned, way of making documentaries, it worked because the film was intended for television rather than the movie theater. And soon we got a letter of commitment from the local PBS affiliate, WFYI, to be the presenting station.

LW: This is so interesting. The local PBS station was supporting the project from the beginning. You didn’t have to approach PBS with the final finished project.

EC: Yes, and our financial sources ended up being local for what was a local project, which made sense to me. I think there’s a kind of intimacy, importance, and immediacy in focusing just on local community, rather than national community.

LW: It sounds like from the beginning the project has garnered a massive amount of local support—from your university, community members, the local TV station, people involved in the film business, and people who are plainly interested in this topic. How did knowing the magnitude of this support affect you as you were making this project?

EC: It more than inspired me. Since much of this was occurring during the pandemic, it made me feel a deep sense of connection to members of my own community—not just Arab Americans, but also the institutions, the filmmakers, everyone involved in the project. And that feeling of connection couldn’t have been timelier because I felt so isolated by the pandemic. Those connections meant that the work mattered to someone else. And that was very important. It’s not just about an audience. It wasn’t about finding an audience that would consume what I was producing. It was about finding people with whom I would make what I was co-producing. And that’s what I understand public history to be.

We shot the movie in the summer of 2021, and it premiered in June 2022, the same time that the book is published. At the same time, the blog became more popular; at this point tens of thousands of people had seen the blog. The movie started streaming on PBS national and debuts on all the local PBS affiliates across the state of Indiana.

In addition, we worked with Indiana Humanities to hold twenty different screenings of this film and dialogues throughout the state. Indiana Humanities really extended the life of and multiplied the impact of the film. Then we collaborated with WFYI to create lesson plans based on the film for PBS Learning Media, which is a free online resource for primary and secondary teachers.

Finally, we used the research to create our community’s first historical State of Indiana historical marker at Lucas Oil Stadium, the site of the city’s first Arabic speaking neighborhood. We just dedicated that this in spring 2024, and that marked the official end of what became a four-year-plus-long public history project.

LW: It’s a beautiful story. Do you see this project as more or less being done? It sounds like at this point, for you, Arab Indianapolis is complete.

EC: What my commitment is now is to use the resources and the connections that were created to continue to work with the community to explore and celebrate this history in central Indiana. One of the project’s ripple effects is that the local and state historians are now including us in various sites and narratives. For example, one of the immediate results was that Indianapolis Parks & Recreation, a division of the City of Indianapolis, just installed a historical trail along Riverside Park, which was the site of the Syrian American Brotherhood Hall for decades. That happened because of what we had produced and shared with the public.

The other thing is I have a ready-made resource for my Arab American studies classes. My students will continue to do this type of work next spring during Arab American Heritage Month in April. It’ll continue to have a life inside and outside the classroom for years.

LW: As time goes on, it’s clear that this will be one of those resources that historians will point to as an example of doing local history with successful community collaboration. We see it’s already being included in these cultural trails, so it will certainly have a very long-lasting life beyond the active production. With that said, how does this documentary, Arab Indianapolis, inform our understanding of the history of Arab migration to the United States and to Indiana? And what do you hope that people take away from the film?

EC: If we only ever pay attention to people on the move, we neglect to notice how they build community even in difficult circumstances. It’s not that Arab Americans don’t feel the pain of displacement, discrimination, and violence, but that’s not the only story we should be telling when we look at Syrian, Lebanese, and Arab American migration. It is possible to celebrate one’s culture while also participating in mainstream American culture. It is possible when we are permitted to. We as historians must understand how people work within constraints to make homes and connections not just to other people, but to places as well. And that’s the story of Arab Indianapolis.