Salma Hargal

PEASANT FAMILIES’ JOURNEYS FROM ALGERIA TO THE MASHRIQ (1880s–1890s): PERSONAL CORRESPONDENCE, MIGRATION NETWORKS, AND RESETTLEMENT

Abstract

In this article, I analyze the journey of impoverished

Algerians who became settlers on state-granted lands within the

framework of Ottoman immigration policies and who acquired Ottoman

citizenship under the 1869 Nationality Law. Drawing on a diverse range

of sources—including confiscated letters, Ottoman archival documents,

and French colonial and diplomatic correspondences and reports—I

reconstruct the trajectories of two families who emigrated to Damascus

and Tiberias in Ottoman Palestine. Their experiences shed light on the

interplay between personal networks, the support provided by

trans-imperial family, Ottoman migration policies, and the challenges

posed by ambiguous legal statuses.

ملخّص

يستفي هذا المقال، أتناول مسارات جزائريين استقرّوا في سوريا وفلسطين إبّان العهد العثماني، هربًا من التفقير والتهميش اللذين عانوا منهما في ظلّ الاستعمار الفرنسي. أسلّط الضوء على سُبل منحهم أراضي في إطار السياسة العثمانية للهجرة، وعلى إجراءات حصولهم على الجنسية العثمانية بموجب قانون سنة 1869. انطلاقًا من وثائق باللغة التركية العثمانية، ورسائل المهاجرين المصادَرة من طرف السلطات الاستعمارية، والمراسلات الرسمية الفرنسية، أُعيد تشكيل مساري عائلتين استقرّتا في دمشق وطبرية. تُبرز هذه الدراسة تداخل الشبكات العائلية العابرة للإمبراطوريات، وسياسات الهجرة العثمانية ، وتعقيدات الوضع القانوني للمهاجرين.

On the first day of Ramadan in 1896, Ali Naqasi b. Umar, an Algerian migrant living in northern Palestine, received a letter from his childhood friend, Umar Nayt Ali. Writing from their home village in Algeria, Umar sought advice about emigrating to the Mashriq, asking for details about the journey and the cost of living. Ali, eager to help, replied with precise information: “If you inquire about the price of wheat, it stands at two without crops. . . . If you inquire about agriculture, the land is plentiful and free of charge as the sultan has granted us land without any payment.”1 Ali’s response highlights the personal networks and informal correspondence that shaped Algerians’ migration decisions and facilitated their resettlement in the Mashriq while also encapsulating the broader dynamics of migration from the Maghrib to the Ottoman Empire. By the late 1840s, Damascus hosted one of the largest communities of Algerian exiles within the Ottoman Empire. The Algerian migrants, fleeing French colonial rule, joined millions of newcomers from Crimea, the Caucasus, and the Balkans2 to benefit from the empire’s open-door policies that offered land allotments, military exemptions, and other incentives.3

In this article, I analyze the journey of impoverished Algerians who became settlers on state-granted lands within the framework of Ottoman immigration policies and who acquired Ottoman citizenship under the 1869 Nationality Law. Drawing from Ottoman4 and French archival sources5 and private letters in Arabic,6 this study examines a peasant family living in Flisset Lebhar in Algeria’s Kabylia region as well as their relatives in Damascus and Tiberias. Specifically, I observe the migration trajectory of a married couple and their two children who sought to migrate to Ottoman Palestine in 1888. Their first attempt was unsuccessful because they did not receive land concessions from the Ottoman State; however, they succeeded on their second try and eventually settled in Tiberias. In the course of exploring this family’s non-linear trajectory this article highlights the role of kinship networks in enabling mobility, securing administrative identification, and facilitating access to resettlement venues within the Ottoman Empire. It offers new insights into migration in the late Ottoman empire by examining the interplay between Ottoman policies and the French colonial rule in Algeria.

Contributing both to the study of migration in the late Ottoman Empire and to the historiography of colonial Algeria, I examine the bonds that Algerians maintained in the core Ottoman Empire after the fall of Ottoman rule in 1830, as well as the Porte’s engagement with these colonial subjects. Existing studies rely on French sources and colonial historiography for their conclusions, consequently only highlighting the push factors in colonial Algeria and in turn neglecting the impact of Ottoman immigration policy and influence of established exile communities.7 In this article, I analyze the migratory experience of Algerians to the bilād al-shām,8 emphasizing the roles of Ottoman migration policy as well as the resources and support offered by family and village networks in facilitating travel and integration into the Ottoman realm.

In the continuity of broader scholarly framework established by the works of Julia Clancy-Smith, M’hamed Oualdi, and Allan Christelow, among others—which adopt a transnational perspective on the history of the Maghrib—I situate the colonial experience of Algerians within the broader transformations of the Ottoman Empire during the nineteenth century.9 This case study also contributes to the growing literature on transimperial approaches to the late Ottoman Empire. For example, Lâle Can has examined, as part of her research, Central Asian mobility within the Ottoman Empire, focusing on Sufi activities, shrine visits, and the Mecca pilgrimage. Can demonstrates how these Muslims leveraged religious mobility in a colonial context to emigrate to Ottoman territories, highlighting the broader role of Sufi networks in engaging with transimperial politics.10 As most current scholarship focuses primarily on migrants from the Caucasus, Crimea, and the Balkans, the Algerian experience offers fresh insights into migration processes, settlement patterns, and mobility control within the Ottoman realm.

As will be further explored, the status of Muslim Algerians, who were French colonial subjects living in the Ottoman Empire, could be ambiguous and spark conflicts. This case study illustrates how these Algerians navigated such challenges by assisting local authorities in duly identifying them as Ottoman citizens. In exchange for renouncing their French subjecthood, these Algerian immigrants were granted broader rights than those typically afforded to other immigrants and refugees. Examining naturalization as part of the settlement process broadens our understanding of muhacir (Muslim immigrants and refugees) as a status that confers specific rights.

In the first part of this article, I describe the circumstances of departure from colonial Algeria through letters exchanged between the peasant communities that remained in Algeria and those already established in the country of destination. The second part explores the key issues surrounding the settlement of migrants in the late nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire. By examining the return of Umar Naqasi, Malika, and their children to Algeria, I identify the challenges immigrants might have faced during their journeys, particularly those stemming from the ambiguity of Algerians’ legal status within the Ottoman Empire. Focusing on the second departure of the family to the Middle East in 1892, I question how the migrants invested in their relational networks to overcome these difficulties and what agency they yielded as a consequence.

PERSONAL CORRESPONDENCE AS MEANS OF FAMILY COHESION AND SHARING MIGRATION KNOWLEDGE

Following the French conquest of Algiers in 1830, many inhabitants of the former Ottoman province emigrated to neighboring Morocco and the Beylik of Tunis, as well as to the Mashriq.11 The community of Damascus was initially established by former resistance leaders who fought against the French army in the 1830s and 1840s and later received allocation from the Ottoman state to resettle after 1849.12 Other Algerians found refuge in Istanbul, Adrianople, Anatolia, and Hijaz. Nonetheless, Greater Syria became home to a significant portion of the Algerians living in the Ottoman Empire. Many worked as farmers on the land provided by the Ottoman government as part of its agricultural development and migrant resettlement policies, especially in the districts of Safed and Tiberias.13 Others were appointed to military and administrative positions within the Ottoman state.14 Algerian immigrants also engaged in manual and intellectual professions in major urban centers such as Damascus, Beirut, Aleppo, Haifa, Jaffa, and Jerusalem, where they served as teachers, clerks, or qadis (Islamic judges), or worked in factories—primarily in spinning mills—and various businesses.15

Meanwhile in Algeria, the colonial order began to harden in the 1870s, which further codified the inferior legal status of non-citizen Algerians and facilitated the expansion of European colonization.16 In fact, Napoleon III’s 1865 decree designated Muslim and Jewish Algerians as French nationals, which meant they legally belonged to the French state even if they left Algeria, though they were not afforded full citizenship.17 In 1870, the Crémieux Decree extended French citizenship to Algerian Jews, excluding those living in the Sahara Desert regions annexed after 1870.18 Muslims or Saharan Jews who wanted to become citizens had to initiate naturalization procedures. By acquiring French nationality, they ceased to be governed by Muslim or Jewish personal law and instead were subject to the Civil Code. Throughout the colonial period, only a few hundred individuals applied for naturalization.19 Non-citizen Algerians were subject to specific taxes and penalties, which further impoverished them and jeopardized the property of those who still owned land.20 For example, Ali Naqasi, who sent the letter quoted above, left Tifra in 1888 with his wife Um al-Khair and their five children after years of poor agricultural yields forced him to sell his modest properties. The 375 francs he earned barely covered the cost of their journey by ship.21

Despite the distance, the peasants of Tifra and Aït Zrara in the Kabylia region kept their familial and village ties alive, mainly through letters. Analyzing the letters’ contents reveals the various forms of solidarity that connected the remaining communities in Algeria and the immigrants in the bilād al-shām, as well as the stakes of emigration for non-citizen Algerians to the Ottoman Empire. Before the First World War, letters and information were passed mainly through traditional communication channels, such as pilgrims, ulema (Muslim religious scholars), and traders. As shown by Annick Lacroix, the new postal system became a primary communication tool in the colonized environment only from the beginning of the twentieth century, although a few isolated uses were attested before 1900.22 The French authorities were aware of the risks involved in these letter exchanges and thus considered the post office as a means of monitoring and preventing migration to the Ottoman Empire.

When the families from Tifra and Aït Zrara departed their villages in October 1895,23 the administrator of the commune of Azeffoun intercepted and confiscated the folds sent by the immigrants to their parents who remained in Algeria. These folds were five letters enclosed in three different envelopes, addressed to family members from the peasant community of Tifra,24 and exchanged by farmers or simple traders who entrusted their writing to literate people.25 Although the sources at our disposal do not allow us to identify all the scribes, the authors had recourse from public writers and religious leaders who also emigrated to the bilād al-shām. Two letters were written by a certain Tahar b. al-Hajj Muhammad, the son of a sheikh of the Rahmaniya Sufi brotherhood26 who had settled in Damascus. These letters were important to the inhabitants of Flisset Lebhar’s tribe where the two villages were located. Peasants in this coastal area, where there are many ravines, mostly engaged in tree growing and crafting, and lived a relatively rough life.27

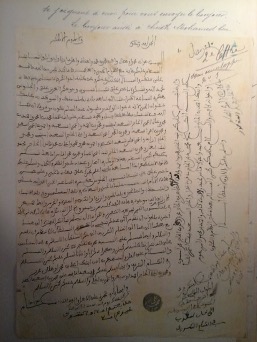

While the letters seem to have different authors, they are based on the same principles of epistolary writing.28 The excerpt from the letter of Ali b. Muhammad Uhlal to his family who remained in Tifra begins with greetings addressed to the principal recipients, explicitly named, as well as to other persons, whose relationship to the author is the only identifying piece of information indicated: “To my father Muhammad Uhlal and my brother Muhammad b. Muhammad and my two sisters and the members of our family and our maternal uncles and our beautiful families, we greet you.” Then, the writer uses vows as a religious formula that also appears in the other letters: “We wish you perpetual well-being, if you are well, it is thanks to God.”29 The texts end with greetings addressed by proxy to other migrants: “Greetings transmitted through your brothers” (Ar. As-salām bi-lisān iẖwāni-kum) to their relatives who remained in the village (Figure 1).30 These greetings, addressed to many people, and the several invocations reflect the influence of the epistolary genre in classical Arabic literature31 as well as the desire of the senders to perpetuate family bonds and community despite the distance.

The intimacy of family gatherings in the village seems to be replicated in the scriptures. A repetitive format referring to these moments is noted: “Nothing would give me more happiness than to sit with you” (Ar. Mā ẖaṣṣa ʿalaya hatā šay siwā al-julūsu maʿa-kum). The letters intercepted in Algeria recall the “bowing letter” model developed by William Thomas and Florian Znaniecki in a classical study of migration sociology published in 1918. Polish peasants adopted a “ceremonial” script in their letter exchanges between the United States and Western Europe. The latter was also characterized by the recurrence of religious formulations and greetings as well as wishes addressed to relatives. Moreover, the writing style of Algerian letters strongly suggests that these were written to be read aloud to the family members and/or the gathered villagers.32 The letters ended with the expression: “Greetings to those who read and those who listen” (Ar. As-salām ʿalā al-qāriʾ [wa] al-mustamiʿ).33 This formula emphasizes oral transmission to recipients who may be illiterate. Thus, the migrant correspondence aims to foster kinship ties despite the distance and separation due to emigration.34

This practice of correspondence encouraged remaining Algerians to join their relatives in the Ottoman Empire. In one of the intercepted letters, Ali b. Muhammad Uhlal tries to convince his parents to join him. He wrote that he was ready to ask the Ottoman authorities for permission to pick up his father and brother who had remained in Tifra: “If you want to come, I ask for a passport (Tr. tezkere35) from the Sultan of Islam and I come to pick you up.”36 Nevertheless, this is an exception in our corpus. The authors of the other letters do not explicitly encourage their relatives to follow them. Since the colonial authorities only occasionally opened these folds, I cannot assume this was due to the fear of reprisal. However, evoking their condition of life in the Levant, they described it as a land of prosperity and abundance in contrast to a poverty-stricken Algeria: “In this country [the bilād al-shām], the poorest live there as the richest of us. We thank God for who we are.”37 The authors of the letters frequently employ religious metaphors and expressions to encourage their relatives to join them. Interestingly, they make no mention of any Islamic obligation to leave French-ruled Algeria.38

During the late nineteenth century in Algeria, French authorities frequently restricted the movement of colonial subjects, particularly when they intended to visit the Mashriq. Paris feared that these circulations would stir up an anti-colonial feeling or harm France’s image abroad. Owing to this repression, access to migratory information, such as the cost or stages of the journey, became a crucial issue for future migrations. It was passed through communication channels between members of the same families, villages, and brotherhoods in the Ottoman Empire.

Take, for example, the letter of Ali Naqasi b. Umar, a peasant residing in sanjak of Safad, where he cultivated land granted by the Ottoman authorities. This letter details his response to his cousin Muhammad b. Said b. Umar’s queries about joining him in the bilād al-shām. However, Ali Naqasi does not give any indication of the Algiers prefecture’s administrative procedures for obtaining a passport for Syria. Under French colonial law, non-citizen Algerians were prohibited from traveling within or beyond Algeria without obtaining prior permission from the authorities. For international travel, they were required to request a “passport” from the local prefect who could only issue this document following approval from the General Government of Algeria. Applicants had to provide a valid reason for their departure and specify the duration of their travel. These documents also recorded the intended destination region. For those seeking to travel to bilād al-shām , non-citizen Algerians had to apply for a passeport pour la Syrie.39 However, French authorities frequently barred Muslim Algerians from traveling to the Mashriq, viewing such movements as potential sources of political unrest and furthering the spread of epidemics.40 Therefore, the recommended route was de facto, which allowed one to escape the control of the French colonial authorities. Thus, Ali Naqasi advised his cousin to go to Algiers at dawn on a Friday with the specific aim of talking to someone at the port of embarkation of British maritime traffic designated as “steam of the British” (Ar. babūr al-inǧilīz). In particular, Ali Naqasi shared that he should speak with one of the British line’s employees, Ahmad Akarnab. Ali Naqasi explains that English ships do not systematically check the passports of Muslim Algerians, which would allow them to bypass border control.41 From then on, the employee of the line—in this case, Ahmad Akarnab—became the key character for migrants at the start of their journey because the employee facilitated access to their means of transport.

Using this information, migrants could easily take the sea route, which was less difficult than the land route. The letter also indicated the fare for each stage of the journey. The first was to reach Tizi-Ouzou and then to Algiers, where the travelers boarded the British ship to Port Said (Egypt). From there, they proceeded by boat to Beirut and continued their journey to Damascus by land. This journey cost 78 francs per individual,42 which was high for many farmers, especially large families. Hence, Ali Naqasi recommended that his cousin sell his property to cover the expenses of the trip. In the 1880s, the deflation made maritime traffic accessible to a large population. Although the cost was high, it was not unaffordable for farmers who made financial sacrifices, such as savings or selling their family assets. In any case, increased access to steamboats further promoted the mobility of Algerian Muslims in the Mediterranean area and the rest of the world.

Ali Naqasi’s letter further illustrates the central role of correspondence in the development of migratory projects. Thus, the letter functions as a space for consultation and for sharing the migratory information necessary to plan for and anticipate the costs of the trip. I also noted that the potential migrants thanked their families and village networks who were in contact with the key players in the migration trajectory, like Ahmad Akarnab. Maintaining a connection between immigrants and their families and village members encouraged departures among the remaining communities, especially considering the destination’s significant attraction factors. The settlement and integration of the first arrivals in their destination the Mashriq coupled with their improved economic situation served as support for future migrants. The exchange of information between families and villagers in the countries of origin and destination linked them to a wide relational network of intermediaries who could facilitate travel and settlement in the host country. This support also included sharing financial and material resources.

Joining the first migrants became possible for Algerians wishing to improve their living conditions and escape a colonial order that relegated them to a subordinate status. They were aware of the support of their relatives who had already settled in the region and knew that they could have access to these different sectors of activity. Consider another case relating to Ali b. Muhammad Uhlal, the author of one of the letters. After becoming a shopkeeper in Bab Suwaiqa in Damascus, he encouraged his father and brother in Algeria to join him to work in the shop.43 However, more than half of the Algerians of the bilād al-shām were like Ali Naqasi, settled in rural areas in which they benefited from Ottoman migration policy.

For the Ottoman government, the influx of immigrants allowed them not only to fill their demographic deficits but also to establish the sovereignty of the state in the rural peripheries.44 Thus, in the middle of the nineteenth century, the Ottoman government adopted a policy of migrants, refugees, exiles and nomads’ resettlement (Tr. iskân45), which coupled the distribution of land for development with tax privileges and assistance for the newly arrived. The policy of attracting migrants with new lands, initially part of Ottoman reforms of the Tanzimat period (1839–1876),46 aimed to bolster the empire’s agricultural production by encouraging immigrants to cultivate untilled state land (Tr. mīrī).47 In essence, migration laws echoed the 1858 Land Law that encouraged the purchase and the exploitation of state-owned lands.48 The other Algerian migrants, among the wealthiest, directly acquired the state lands that the state sold at auction. Abdulkarim Rafeq described that Amir Abdelkader (1808–1883)49 established an agricultural estate in the vicinity of Damascus, taking advantage of the liberalization of the land market in the Tanzimat era. Those who were granted state-owned lands gained access to the ownership of the land after varying periods.50 Thus, the Ottoman settlement policy allowed the immigrants to gain financial autonomy while promoting imperial agricultural production.51 Access to these lands was not always an easy undertaking. As a result, many migrants were forced to return to Algeria because they could not find sufficient livelihoods. The case of Umar Naqasi and Malika underscores both the obstacles encountered by Algerian immigrants and the ways to overcome these difficulties.

OTTOMAN NATURALIZATION AS PART OF THE RESETTLEMENT PROCESS

In 1888, Umar Naqasi and Malika decided to sell their property and emigrate to the Ottoman Empire with their two children. According to the arguments put forward by Umar to obtain an external passport, he made the decision because of a succession dispute between him and his in-laws.52 Nonetheless, the departure was in the context of a wave of emigration of inhabitants of the countryside of Great Kabylia and the Constantine region to the bilād al-shām following a period of drought and locust attack during the agricultural season. Kemal Kateb puts the figure of 856.53 I counted 347 in the archives of the Center of Diplomatic Archives in Nantes (CADN), and which were not informed in the files of the Archives nationales d’outre-mer (ANOM) related to migration in Syria. These would be 1,203 in total. However, the actual number may still be higher. These natural incidences threatened the economic survival of a population already impoverished by land dispossession and the weight of taxation and penalties specific to non-citizen Algerians.54 Some of those who emigrated on this date, including Malika and Umar Naqasi, returned to Algeria just two years later.

Those who did not receive their land grants in time were forced to return to Algeria after having exhausted all their savings.55 Among them, 205 from the Constantine region obtained the right to free repatriation from the consul general of France in Beirut.56 The deputy governor (Tr. mütesarrıf) of Acre alerted the Sublime Porte of such requests through the governor of Beirut. Therefore, the procedure for granting the promised concessions was accelerated to avoid repatriations. Finally, only 98 Algerians were repatriated.57 This reaction was part of a policy of repression of Ottoman departures abroad from the 1880s, partially driven by political considerations.58 According to Istanbul, the emigration of the Ottomans impaired the image and prestige of the caliphate.59 Having already sold their land and livestock in Tifra before emigrating, Malika and Umar Naqasi, and their two children, remained without financial resources and decided to return to Algeria.60

During that period, Ottoman authorities sometimes restricted the settlement of Algerians due to the ambiguity surrounding their legal status. Abroad, since the aforementioned Napoleon III’s decrees, Muslim and Jewish Algerians, citizens or not, were granted de jure the same consular protection rights as the French. The status of “protégé” conferred various extraterritorial privileges including tax and military exemptions.61 Simultaneously, Ottoman authorities regarded permanent settlers as their nationals.62 In the 1880s, tensions peaked when Algerians, who were considered as Ottoman citizens by local authorities, sought refuge in the French general consulate to evade legal prosecution or military conscription. This situation triggered diplomatic conflicts as Ottoman gendarmes entered the consulate to arrest them.63 Delays could also be attributed to other factors. Following the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, the Porte prioritized settling Circassian war refugees in its Arab provinces, overshadowing the needs of North African migrants.64 Financial difficulties during the global Great Depression (1878–1896) further exacerbated the situation.65 Additionally, responsibility for land allocations was divided between provincial authorities and the Ottoman central government, but issues like understaffing, file overload, and high turnover among provincial governors during the reign of Abdülhamit II (1876–1908) hindered effective management of migrants’ resettlement.66

Meanwhile, in the winter of 1889, Sultan Abdülhamit II and the French ambassador Gustave de Montebello reached an agreement regarding the legal status of Algerians residing in Syria and Palestine. The French government agreed to cease granting consular protection to Muslim and Jewish Algerians who had permanently settled in these regions. In return, the Ottomans agreed to recognize the French nationality of Algerians only when they were transient (de passage) within the empire’s territories for less than two years. However, Algerians who cultivated or sought to cultivate state lands, as well as those who married Ottoman citizens, were to be considered Ottoman subjects regardless the date of entry.67 As part of the agreement, the Ottoman authorities also committed to providing French consuls with lists of naturalized citizens, enabling the French to revoke their consular protection rights. To encourage most Algerian migrants to register as Ottoman citizens and renounce their French nationality, Abdülhamit II offered them specific privileges, which included increased land concessions and an extension to their military service exemption period to twenty years.68

Three years later, Malika and Umar Naqasi embarked again to the Ottoman Empire with twenty-three other peasant families. This time, the departure was organized by a Muhammad b. Salim from the bilād al-shām, who had returned to Algeria to look for family members and other migrants. He had maintained correspondence with the governor of Beirut, Halid Bey Effendi (1892–1894).69 The group left Algeria on 8 October 1892 and arrived a month and a half later in Beirut after a passage through the port of Alexandria.70 Indubitably, the identity of Muhammad b. Salim is obscure. However, he is referred to in Ottoman Turkish as “şeyh-ü şerīf,”71 suggesting that he was a religious dignitary since the name b. Salim refers to the zawiya72 of Sidi Salim in Bouira belonging to the network of the Rahmaniya brotherhood.73

Their passports issued by French colonial authorities indicate that they originated from communities along the Sebaou River in Great Kabylia. Nonetheless, our sources do not reveal how these families were acquainted with Muhammad b. Salim, although there were many opportunities for the encounter. In addition to the ancestral commercial practice of peddling, markets located in bordering places between several tribes functioned as places of meetings, contacts, and exchanges. Also, visits to the shrines of saints (Ar. ziyāra74) (i.e., local pilgrimages) were crucial in connecting the peasant communities.75 In Ottoman sources, Muhammad b. Salim is referred to as the “chief of migrants from Algeria” (Tr. Cezāyir muhacirlerin reʾisi). The Turkish term re’īs refers to the heads of caravans (Tr. ḳāfile) and/or tribes (Tr. ḳabīle), as illustrated by similar documents on Caucasian migration. These dignitaries are similar to Muslim religious scholars and those with a prophetic ancestry (Tr. ʿulemā ve eşrāf), distinguishing them from the rest of the migrants. Thus, Muhammad b. Salim might be the privileged interlocutor for the Ottoman authorities who identified the twenty-four migrant families as his “companions” (Tr. rüfeḳā).76

Initially, the Ottoman government issued a firman installing the group of Muhammad b. Salim in the sub-province (sancak) of Acre. This decision, communicated to the governor of the province by telegraph, was issued before the migrants arrived in the bilād al-shām.77 Upon their arrival in Beirut in November 1892, Muhammad b. Salim sent a letter through a public writer specializing in petitions (Tr. arz-ı ḥalcı) to ask the governor of Beirut to order the execution of the firman.78 The petition expressed the migrants’ allegiance to the sultan-caliph, as is customary in such documents, and those who were not yet naturalized requested to become imperial citizens:

Your humble servant residing in Algeria has now migrated to this side [Beirut] in the company of twenty-four families, who form a population of 150 men and women, with the sole intention of taking refuge under the prosperous wing of its imperial excellence and being granted the honor and glory of Ottoman nationality. Of grace and favor that it is deemed worthy by Your Excellency the Protector of the Governorate to grant your sublime permission to the resettlement of your servants in an adequate district of your illustrious province so that they may engage in agriculture. In this regard and any event, the order and decree belong to His Excellency, who holds authority.79

The Ottoman Government signed the petition and instructed the governor of Beirut to naturalize these Algerians by virtue of the 1889 French-Ottoman agreement. Given Muhammad b. Salim’s personal connections with these migrant families, the government ordered the governor of Beirut Halid Bey Effendi to assign b. Salim to provide identification data about all the members of the group. The Algerian intermediate created a register that included the first and last names of each family’s members, each family’s date of immigration, the geographical origin of each family’s father, and each family’s composition. In addition, the list included the dates of document issuance for those who had French passports. The 1889 agreement stipulated that the delegates from the Ottoman Empire and the French consulate compile a list of migrants for registration with both states.80 Given his substantial role in managing the naturalization process for the Algerian migrant group, Muhammad b. Salim urged the governor to expedite their resettlement. Nonetheless, three months after fulfilling the requested procedure, he still did not receive the concession promised by the Ottoman government. Hence, he sent a telegram to the authorities on 30 May 1893, drawing attention to the precarious situation of the members of his community:

We accepted the Ottoman subjection and have not received the order for our installation. The French Consul in Safed has examined our passports. The [Consul] General can no longer provide us with protection. Our precariousness worsens, we become miserable, and we demand assistance. Safed authorities know that we’ve immigrated. If you do not settle us as you81 did for our compatriots (Tr. hemşehirlerimiz), please have the clemency to repatriate us to Algeria for free.82

When migrants did not lodge on their own, they were placed by the provincial authorities in the homes of inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire.83 During this time, the families constituting Muhammad b. Salim’s group might have been temporarily accommodated in northern Galilee because b. Salim was now corresponding with the French consul of Safed and no longer with that of Beirut. Without an official response, the migrants became poorer as they depleted their resources. Thus, Muhammad b. Salim leveraged the renunciation of French nationality as a key argument to pressure the governor to resettle the families. He also pressed the issue further by suggesting their repatriation to Algeria, despite their status as Ottoman citizens.

In July 1893, the governor of Beirut received an order from the Ottoman government, which officially granted the land to the community of Muhammad b. Salim. Would the repatriation option mentioned in the telegram have pushed the Sublime Porte to act faster? The available documents do not allow us to investigate this situation; however, it should be noted that the Ottomans considered the return of migrants as a plausible attack on the prestige of the empire. However, the Grand Vizier confirmed that the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs had just considered the Ottoman naturalization of newcomers. Thus, it is probable that a procedural delay had hampered their installation. Since the group departed from Algeria covertly and only a third of them had (already expired) passports, the consular authorities had to verify their Algerian origin with the French administration in Algeria. Notifying the French consuls about the Ottoman naturalization of immigrants was crucial because it prevented the muhacir from availing of the consular protégés privileges of exemption from taxes and military conscription.84

Finally, the Ottoman government decided to set up the group in the villages of Kafr al-Sabt, Shuwarah, and Awlam,85 located in Shafa Amr, near Mount Tabor, in the Tiberias district, thereby providing them with fertile land in the vast plains surrounding the Galilee Lake. Ottomans assigned the Algerians, who migrated to the bilād al-shām after the suppression of the 1871 uprising that had spread over Great Kabylia and part of the Constantine region, to settle in these abandoned villages. As Muhammad b. Salim and his companions knew of these villages before their departure, we can presume that the migrants found this decision satisfactory.86 In the petition, Muhammad b. Salim asked that his group be installed in the same manner as other Algerians in Tiberias. Since the Hamidian period (1876–1908), the Ottomans were inclined to disperse geographically migrants of the same religious, ethnolinguistic, and national groups so as to suppress any potential separatist tendencies; however, the Ottoman authorities often yielded to migrant demands when some refused the assigned location. For example, when the Ottomans proposed that the Cretan migrants settle on fertile grounds near Konya, they instead sought resettlement in Izmir with other Cretan nationals.87

Another hypothesis is that the Ottoman state could not always manage the migrants’ demands, which prompted them to search for suitable land for themselves or their relatives who planned to emigrate. The Ottoman Government then ordered resettlements on the lands proposed by the migrants. Thus, the military leader Çürüksülü Ali Pasha, stationed in Ordu (Trabzon) after the war of 1877–1878, along with 6,000 other Georgians, cleared and drained the marshland to free up space for newcomers before the newcomers could claim the rights to usage.88 It can thus be speculated that Muhammad b. Salim took advantage of the Algerian anchorage in Galilee to find adequate land in the vicinity of Kafr al-Sabt, Shuwarah, and Awlam, and made a concession proposal to the Ottoman Government.

Finally, reconstructing these stages sheds light on new facets of migration in late nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire. Our case study reveals the provincial governor’s key role in migration policy and the ability of migrants to negotiate the conditions of their resettlement through their literate elites. However, these local dynamics were constrained by the central state, which reserved the right to formalize the granting of state lands. The Ottoman government also ordered the inclusion of future beneficiaries in the registers of civil status (Tr. sicill-i nüfüs), demonstrating the importance of the Ottoman naturalization of Algerians.

CONCLUSION

In 1908, an estimated 16,000 to 20,000 Algerian migrants lived in the bilād al-shām.89 Beyond this case study, this article highlights the connections that Algerians maintained within the Ottoman realm, spanning generations and persisting over half a century after the French conquest of Algiers in 1830. In a context of worsening social conditions and increasing political exclusion, Muslim Algerians leveraged these networks to build better lives in the Ottoman Empire. Those who remained in Algeria shared their living experiences with their relatives in the Mashriq through regular correspondence. These forms of cross-border solidarity are not peculiar to the colonized. However, this exchange of information facilitated covert emigration, despite the colonial authorities’ attempt to limit Algerians’ departures to the Mashriq. Additionally, the presence of Ottomans originating from Algeria in the Maghrib enabled prospective migrants to establish connections, namely with state agents, in the destination country. The case of Ali Naqasi’s family shows how Sufi visits and commercial gathering in the Kabylia region fostered the creation of these bonds, while the experiences of Ali and Umar Naqasi underscore the pivotal role that literate members of these networks played in the migration and resettlement process.

The Algerian experience also sheds new light on Ottoman resettlement and nationality policies in the late nineteenth century. Existent scholarship on the public governance of migration examines cases of newcomers from Crimea, the Caucasus, and the Balkans. This study contributes to that historiography by demonstrating that, in addition to the muhacir status privileges extended to migrants from the Maghrib, the conditions of resettlement could vary across different communities. Since Algerians could claim extraterritorial privileges as French nationals, their formal renunciation of their legal belonging allowed them to negotiate for greater privileges. This article shows how settled Ottoman Algerians became intermediaries between newly arrived compatriots, French consuls, and local administrators. Figures like Muhammad b. Salim, who were embedded in Algerian society and connected with Ottoman authorities, played a crucial role in the identification and resettlement of fellow Algerians. As such, a relational approach to migration offers new insights into the successes and challenges of Ottoman public policy towards migrants.

While recent studies on French colonialism in Algeria have predominantly focused on the conditions of impoverished non-citizen Algerians,90 this article goes further to explore how these colonial subjects emancipated themselves by settling abroad, particularly in the Ottoman Empire. A comparison with similar cases of Indian or Central Asian migrants91 reveals that the Ottoman Empire became a destination for immigration where the colonized—from former Ottoman provinces or not—could not only improve their material wellbeing but also escape subordinate legal status. In the Ottoman realm, they potentially benefited from muhacir privileges, and they were able to integrate into an equal Ottoman citizenship.