Refqa Abu-Remaileh & Lindsey Waldenberg

TRACING PALESTINIAN LITERATURE: AN INTERVIEW WITH REFQA ABU-REMAILEH

Abstract

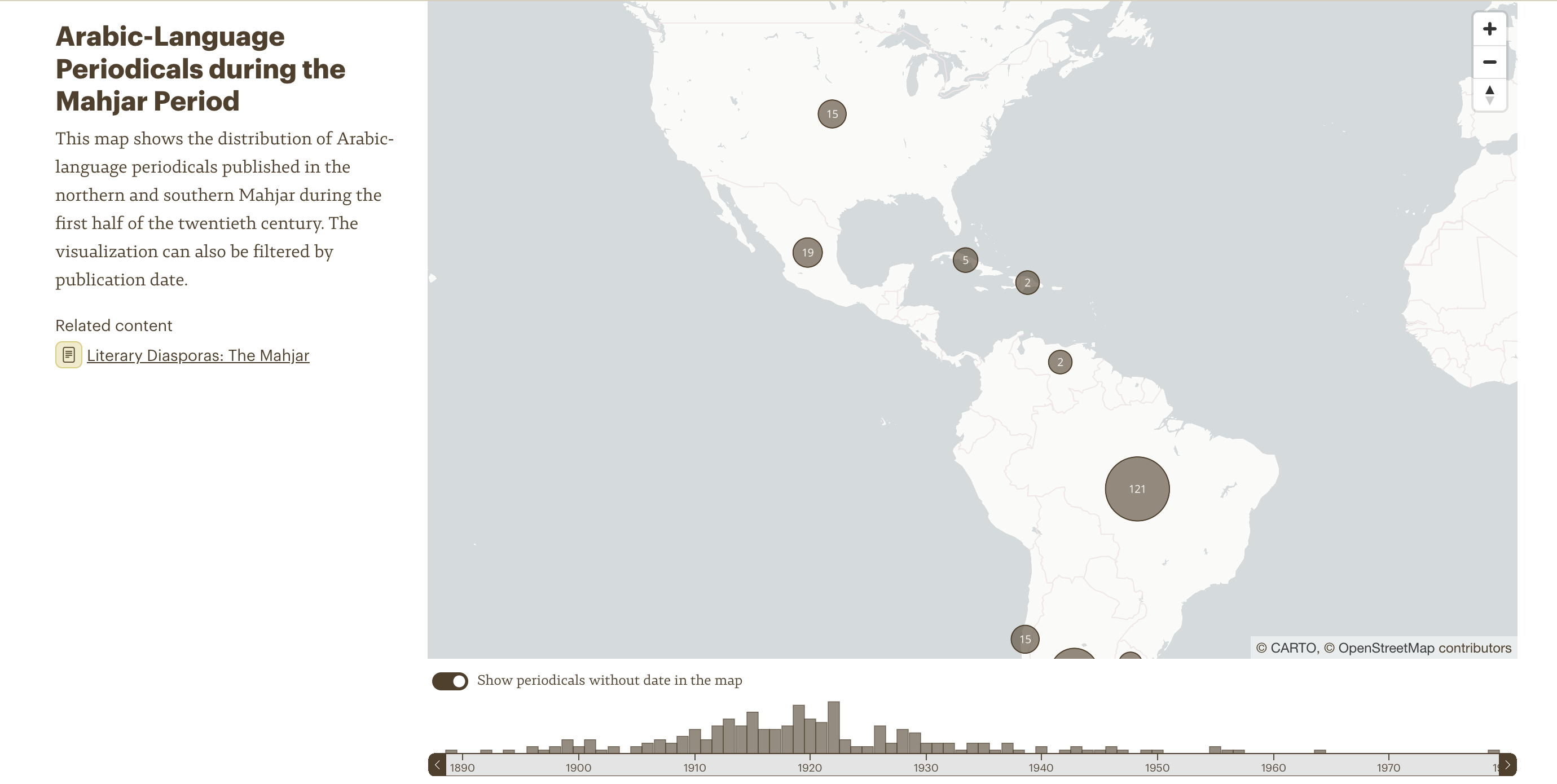

In this interview, Dr. Refqa Abu-Remaileh discusses her new project, Country of Words: A Transnational Atlas for Palestinian Literature. Country of Words combines literary history, a rich and expansive set of primary sources, and digital humanities tools to trace Palestinian literature’s development in the twentieth century. Abu-Remaileh resists the de facto use of the predominant nation state framework to categorize Palestinian literature, an approach, she asserts, that is inadequate for conveying continuities between periods and literary geographies. Instead, Country of Words demonstrates the possibility of methodologies for studying the creation and dissemination of national and exilic literature beyond set physical and temporal borders. Her project primarily uses periodicals published throughout the Arab world and across the North and South American mahjars to demarcate Palestinian literature’s development into seven separate, though sometimes concurrent, periods. Coupled with the use of digital humanities tools, her project offers readers the opportunity to not only interact with a comprehensive overview of Palestinian local and global works but also consider the overlapping networks and trajectories that characterize and continue to shape this literature. This interview discusses the project’s inception, accomplishments, challenges, and impact.

خلاصة

في هذه المقابلة، تناقش الدكتورة رفقةأبو رميلة مشروعها الجديد "بلد من كلام: أطلس عابر للحدود الوطنية للأدب الفلسطيني". يجمع كتاب "بلد من كلام" بين التاريخ الأدبي، ومجموعة غنية وواسعة من المصادر الأولية، وأدوات العلوم الإنسانية الرقمية لتتبع تطور الأدب الفلسطيني في القرن العشرين. تقاوم أبو رميلة استخدام إطار الدولة القومية السائد لتصنيف الأدب الفلسطيني، وهو نهج، كما تؤكد، غير كاف لنقل الاستمرارية بين الفترات والجغرافيات الأدبية. بدلا من ذلك، يوضح كتاب "بلد من كلام" إمكانية وجود منهجيات لدراسة إنشاء ونشر الأدب الوطني والمنفى خارج الحدود المادية والزمنية المحددة. يستخدم مشروعها في المقام الأول الصحف والمجلاتالمنشورة في جميع أنحاء العالم العربي وفي الجاليات الفلسطينية في أمريكا الشمالية والجنوبية لتقسيم تطور الأدب الفلسطيني إلى سبع فترات منفصلة، وإن كانت متزامنة في بعض الأحيان. إلى جانب استخدام أدوات العلوم الإنسانية الرقمية، يوفر مشروعها للقُرّاء الفرصة ليس فقط للتفاعل مع نظرة شاملة للأعمال الفلسطينية المحلية والعالمية، ولكن أيضًا النظر في الشبكات والمسارات المتداخلة التي تميز هذا الأدب وتستمر في تشكيله. تتناول هذه المقابلة بداية المشروع وإنجازاته وتحدياته وتأثيره.

Lindsey Waldenberg (LW): Thank you for sharing your time with us. In going through the website, I was struck by the project’s numerous dimensions and ways to understand the breadth of this literature and to connect the disconnected across time and space. So, I’ll begin by asking, what inspired this project?

Refqa Abu-Remaileh (RAR): One of the inspirations comes from Elia Suleiman’s short film called Cyber Palestine. The film transposes the biblical story of Mary and Joseph, especially their journey from Nazareth to Jerusalem, to modern-day Palestine. In the opening scene of this film, you see Joseph sitting in front of his computer screen and he is typing in a Yahoo search engine. He types the words “Cyber Palestine.” His search yields only a photo of ancient columns and the words that announce that the site is under construction. That scene and that film stuck with me for a long time, and it made me think about the relationship between the virtual and the exilic, and what can the cyber space and the digital offer a refugee and exilic nation if they can’t reach each other or places in the physical world.

And then, there is the Mahmoud Darwish poem that inspired the “country of words” aspect of the project. It’s this idea that people are connected through their words, through their literature and publications, wherever these publications are. In the poem, it says, “but we have a country of words. Speak, speak so I can put my road on the stone of a stone. We have a country of words. Speak, speak so we may know the end of this travel.” And this “stone of a stone” process of accumulation was also something that stayed with me. How do Palestinians and their literature—a literature of an entire nation in exile, this country of words that spread across the globe—connect?

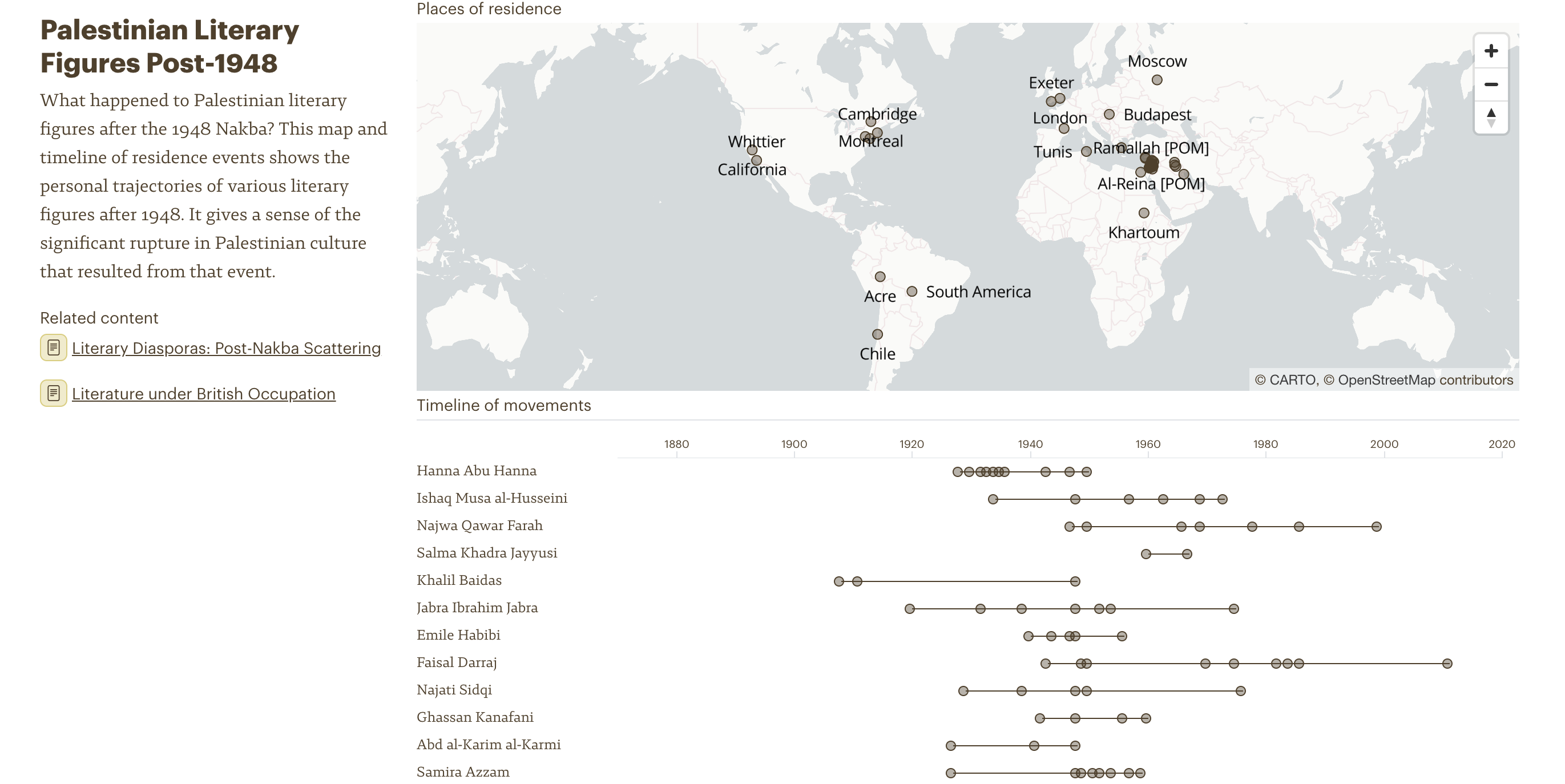

Then I must confess that, personally, I hit a ceiling. I’m a scholar of Palestinian literature and I got stuck. I realized it was because literary analysis was not enough to understand the bigger picture, to see how things connect. The way we study Palestinian literature is usually either we focus on an author, a group of authors, one geographical location, or one period. Most of us who have studied Palestinian literature have always had the post-1948 focus, so we don’t really know anything about earlier periods. So, I hit the ceiling in the sense that the canon, the five people that everybody talks about and writes about—Mahmoud Darwish, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Emil Habibi, Ghassan Kanafani, Sahar Khalifeh, and maybe one or two other names—it was unclear how these people connected to each other. I realized also that each one of these people that we consider part of the Palestinian canon lived, worked, produced, and published in totally different geographical locations; however, the geographical and cultural contexts were never highlighted. When you bring all these people together into one circle, the assumption is that they lived and worked together, operated in the same national infrastructure. That was not the reality. I started thinking about how these people and geographies connect to each other, and how to explore or even identify these connections. This would eventually lead to periodizing in a way that exposes links and connections across periods and across geographies.

Another aim I had was to expand the canon because it seemed that the Palestinian literary canon was shrinking to just a few names, as if there was no one else out there that had written or produced. One aim of this project is to bring on the scene hundreds of names, so that people in the future can have other literary figures to think about and write about and explore.

Basically, I created the project to answer my own questions of how people and places linked to each other, and how these people and places related to periods of Palestinian literary history. At the same time, I started to pay attention to digital projects that were coming out. It’s not a coincidence that there were quite a few Palestinian digital projects, which were very clearly a reaction to these threats of the loss of physical archives or the raiding and confiscation by Israeli authorities of Palestinian archives, which was happening on an ongoing basis in the West Bank, Gaza, and Israel. There seemed to be a need to collect, digitize, and allow this material to be accessible outside of Palestine because Palestine was shrinking as a place. Palestinians in the diaspora couldn’t access Palestine. So, building physical archives didn’t really make sense. It made more sense to have these digital archives that people across the world could access instead of this shrinking geographical space that Palestine found itself in.

LW: I want to touch on the project’s investigation of how these networks interacted with each other. In particular, I was so impressed by seeing the maps of the periodicals: who published what, where, thematic overlaps, and things like that. To that end, could you share why you focused on the periodicals? What else can we get from the periodicals rather than solely poetry or works of fiction?

RAR: The most immediate answer on the periodicals front was the realization that a lot of the original literary contributions in Palestinian literary history, and in Arab literary history in the twentieth century, were originally published in periodicals. Periodicals became very clearly a resource that is almost untapped in terms of studying literature and literary history. A lot of it has to do with access and availability. So that is historically probably the reason why people couldn’t use periodicals as much as we can today. The digitization efforts have really helped, I think.

For example, we came across the work of Ishaq Musa al-Husseini in the Mandate period. In a 1945 article, al-Husseini wrote about Palestinian literature, characterizing it as adab maqalat, as opposed to adab muʾallafat. And here, adab maqalat means “a literature of articles” versus a “literature of books or authored publications,” and that caught my attention. At the time, I didn’t quite understand what exactly he meant, but the more I looked into periodicals, the more I understood that periodicals were actually the literature. For the majority of the twentieth century, this is where you would find original literary contributions as well as debates, events, and topics of discussion.

For me, it’s one of the most malleable sources one could use for research. We took periodicals and analyzed them from cover to cover. Mastheads and editorials became one of the most important things we were able to extract data from. Contents, pages, section headings, contributor networks—there are a lot of things that can come out of periodicals and reading them in different ways. You can extract data, but some things are already on the page that you can read and analyze. You can also extrapolate reader networks, these kinds of transnational links, subscriber networks, and how they reprinted material from other periodicals. Another thing that was an important source for us was how periodicals covered other periodicals, imprisonments, political events, revolts, revolutions, things like that. We paid attention to literally anything that appeared on the page, from a drawing to a section title to page number to a margin to a letter to whatever it was.

LW: I would like to talk about the process of building your own dataset for all these periodicals. It’s very difficult to track down these periodicals and to find copies of them to digitize. I was curious if you could speak about how you tackled that problem.

RAR: Early in the project, I decided that it was going to be more of a database project rather than an archival project, specifically because of this problem of not being able to access the actual sources in many, many cases, especially with these early Mahjar periodicals. The benefit of the database was that even if we could not access the source itself, we could still gather the data. There is the map, which is in the Mahjar chapter of the book, which shows all the periodicals in Latin America and Caribbean, et cetera. We’ve hardly scratched the surface on that one, but we were still able to gather all the titles and as much details as we can in terms of metadata—years, who were the editors, who were the publishers, which locations. Of course, this is all patchy and not very comprehensive or complete, but I had to live with that, which was not easy because we’re always striving for completeness.

But I think in this case, and in the Palestine case, completeness is not something that will ever happen. You must make do with what you can find. The database became the focus of the project. The way this was thought about is that there is no Palestinian literary history that is written that documents and includes the pre- and post-Nakba periods, and the different literary geographies of homeland and exile. That source does not exist, which means that there needed to be data extracted from all kinds of different sources. But we had to decide what kind of data we are going to extract and how we collect, standardize, and visualize it, especially because we did not have the OCR (optical character recognition) software that would allow us to search sources automatically without going through everything manually. This was where periodicals became an extremely important source for data extraction.

LW: It’s not just about finding the information. It’s about, like you said, cleaning it up and making those connections, especially when thinking about themes. I’m particularly interested in the theme of imprisonment being a constant throughout the periods. Could you speak more about why the theme of imprisonment was so constant and how it changed over time?

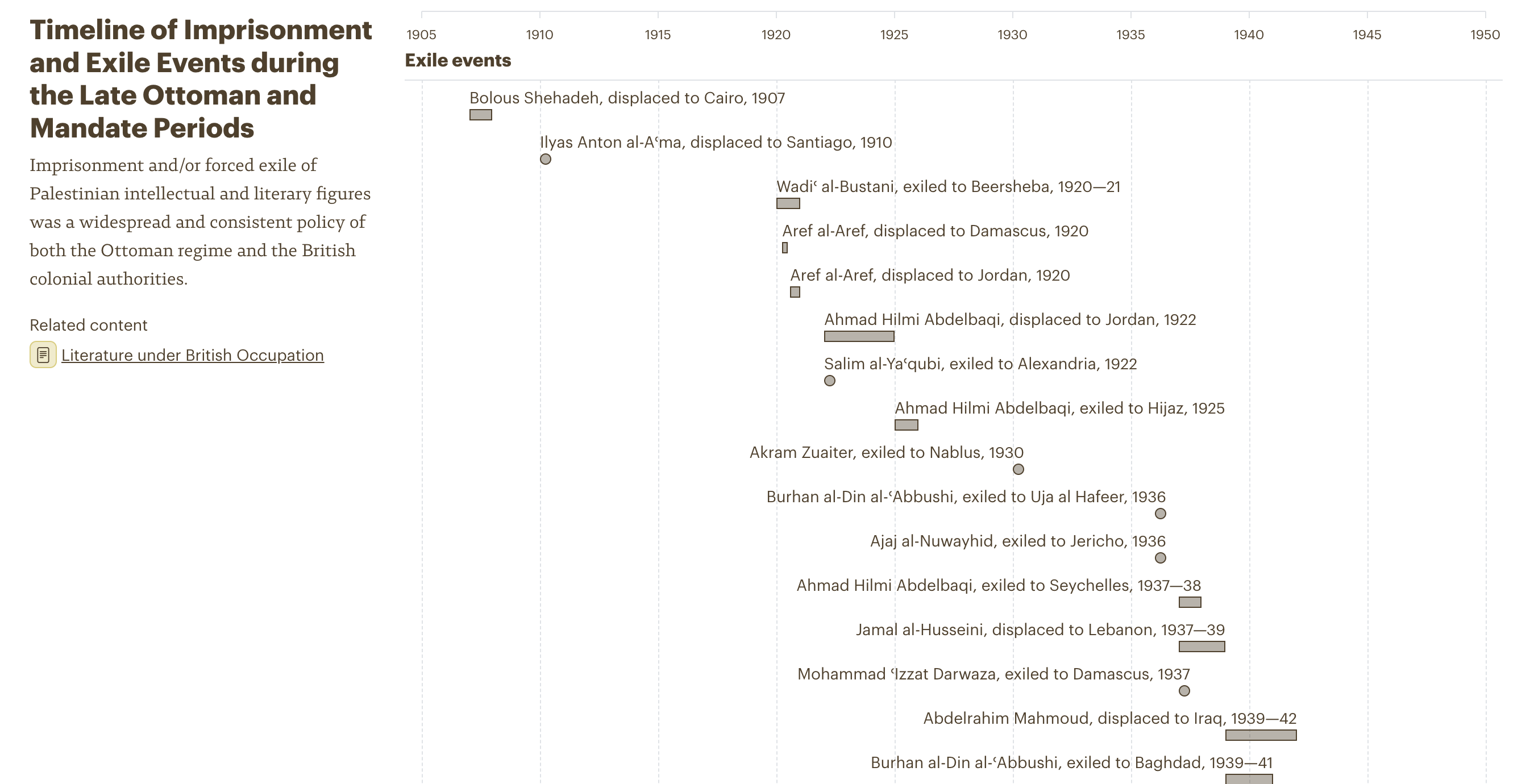

RAR: The theme of imprisonment became important as an aspect of Palestinian literary history that has been sidelined, a little bit marginalized, and often studied totally separately. After having gathered the data, I was aware of this, but I didn’t know how bad it was, this unprecedented number of Palestinian literary figures that were imprisoned, detained, held in administrative detention, placed under house arrest, deported, forcibly exiled, and expelled throughout the twentieth century. It’s something that was always there in the background, and there’s quite a disturbing history of these mass incarcerations, persecutions, and banishment of Palestinian literary figures. The other part of this is trying to bring it into conversation with literary history because it has been studied as if it’s a separate genre altogether. Prison became so important and so clearly integral to Palestinian literature throughout the twentieth century that it was impossible to ignore it.

In referencing it throughout the text in the different chapters, it became clear that prison was a tool of oppression and silencing of Palestinian literary, political, and cultural figures, and it’s disturbingly present in almost all the periods. I saw it as part of a systematic effort to annihilate and decimate Palestinian society and culture across the different periods. This acknowledgement of imprisonment really impacted and influenced the course of Palestinian literature and its literary figures. This very clearly played out on the pages of periodicals.

For example, there is this concept of the “big prison” and “small prison,” which was discussed in an article written by Emile Habibi in 1946. This is before the 1948 Nakba when he used these terms. Palestinians often think of their lives as either in a small prison (the actual prison) or the big prison (which is the country). This thinking persisted. I found reference to this concept in later periods, that Palestinians are living in one big prison. This applies to Gaza also very much right now. But this is a concept that has existed throughout the twentieth century in terms of the Palestinian condition. And this kind of phenomenon of these poets imprisoned under the British colonial authorities, the Israeli authorities, the Egyptian authorities, the Jordanians—there is a phenomenon of poet prisoners in the Palestinian literary context that I wanted to highlight.

Image 3: Interactive timeline of imprisoned and exiled Palestinian intellectual and literary figures. Courtesy of Country of Words.

LW: Picking up on this theme about continuities and links to today, what do you envision for the future of this project? How and in what ways has this project perhaps taken on new or different meanings considering the current siege of Gaza?

RAR: I think it’s quite uncanny and extremely disturbing to realize that what is happening is not entirely new. This is a tragic history filled with attempts at erasure and annihilation, policies to stop and stunt and suspend and prevent and wipe off the map Palestinian presence, culture, history, and identity.

This is a persistent tragedy, and that’s why I also highlight these aspects of Palestinian literary history, especially censorship, imprisonment, and all of that. There have been clear efforts at destruction, but also what I see as “deculturation” or “decivilization.” The wiping out of Palestinian culture at certain junctures of time and between periods meant that people literally had to start from scratch every time because everything they had done before was wiped out. This happened after 1948. It also happened after 1967. It happened after Beirut.

For example, a lot of the periodicals I came across before the Nakba of 1948 were completely wiped out. Not even one of them continued, especially the literary magazines. We have the instance of one newspaper, Al Ittihad, which was the only one that survived. And some had to relocate to other places and eventually didn’t last long. So, in terms of literary culture, it is a story of stunting, stopping, starting from scratch. It’s a very difficult and tragic history in the sense that one couldn’t build on what was happening in the past.

The other thing I wanted to highlight is placing Palestinian people and their culture under siege. This was also something that came up in 1948; for example, Palestinians who remained in Palestine and came under the Israeli military occupation were placed under an isolation where they could not communicate with their relatives, friends, or family who were forced to flee Palestine. They were under siege, and they called it a cultural isolation. These siege and isolation policies were being experienced by Palestinians in different ways under different occupation powers. I mean, the most extreme case is the siege of Gaza and the complete isolation of Gaza from everywhere else. I have to say that for the entire duration of the project, Gaza was the biggest challenge for us. Gaza has been destroyed so many times, that for archives and libraries, you don’t know what survived which destruction. We even hired a local researcher in Gaza, but her work and her movements were limited by assaults on Gaza, by the Covid pandemic, by all sorts of things. It was really difficult to get anything out of Gaza.

LW: Before we look forward to the future, thinking about more of the contemporary connections, you mentioned this is a way to push back against this silencing and make sure that people know these authors and writings existed so we’re not having to start over again. And so, I’d like to briefly touch on the inclusion of your interviews with the different writers as part of that effort. Why did you want to include the interviews as a dimension to this project?

RAR: The interviews were designed specifically to attribute an oral history component to the project. So just as we had to get creative with the sources, we also had to find different ways to gather the data and the information. The benefit of these oral histories is that they filled the gaps where we had no sources or documentation. And there’s very little documentation of Palestinian literary life in all these different places and how they connected to each other. This is what I wanted out of these interviews. I wanted them to focus on these aspects, periods, experiences, and connections that were not documented. So oral history was, let’s say, a source for the data, a source for documentation, a source for connection. But one other thing that was important to me personally was to create something professional that would be accessible as a product to a very wide audience, regardless of the project, and that could outlive the project and have a life of its own. So that’s why it started taking the form of a podcast.

LW: Scholars and the public alike will value those interviews and the entire project for years to come, because clearly in this project, you’re not just thinking about the past, but you’re also thinking about the future and where scholars can pick up from here. To that end, do you see this project as a complete package right now? Do you see it adding onto it as time goes on with different periods, like, for example, right now? And how do you think that this project will shape the field of literary studies or how we approach studying certain literatures?

RAR: The project for me is a beginning because I feel I have a lot more work to do coming out of this project. Also, I wanted it to lay as much groundwork as possible so I can come back to it, but also so other people and researchers can pursue more specific things further and in more detail. And there’s a lot there that I personally couldn’t get into, issues, topics, trends that I came across—too many geographical locations, too many people, periods, and sources to cover. But I wanted it there as a reference and as groundwork for future projects and initiatives.

I have to say that in this process, this Palestinian literary history in its transnational dimensions became my portal to the world. It became my access point to so many things I was unaware of, like for example, the entire mahjar community. It’s introduced me to new fields, new dimensions, new frames of thought and work, and different methodologies and the digital work.

I created the project in this digital format so it can be elastic and open-ended, so it’s not complete and it’s not comprehensive. There’s a lot still to delve into further, but this digital form allowed some flexibility that was forgiving. The digital frame allowed me to capture these overlapping periods that transitioned from being under occupation and in the diaspora and exile, and show how these link to each other, as well as these repetitive cycles of occupation and exile. It allowed me to capture certain things that I wouldn’t be able to capture otherwise. It was an experiment also in digital humanities in the context of Arabic literature and literary history and what we can do with these tools.

I didn’t mention this before, but we did create a custom-made visualization tool for the project which produced all these visualizations. This tool is directly connected to the database. It reads the data from the database, and I can choose to create timelines, maps, networks, temporal evolutions, trajectories, and information cards on people. This visualization tool is a tool for the dissemination of knowledge in a different way. I’m a visual learner, so I was always creating these things for myself anyway. But for the project and to deal with so much data, we had to create these tools.

My aim was to pose the question for the field. How do we deal with a literature-in-motion, a literature that has these all these extra-national dimensions? How do we deal with transnational networks and links? And there I mentioned the unprecedented number of the world’s population living as refugees and exiles. The whole region is in flux, in motion. So how do we study these literary communities when they are outside their nation-state in massive numbers? How do we study these kinds of literary communities that have extra-national forms of production, reception, dissemination, and movement?

This is not just specific to the Arab world. This is impacting the entire world, but literary studies in general is still more or less stuck in the national framework. It was really a question of how we can use different tools, methodologies, and approaches to overcome these challenges.

LW: I think considering approaching this study or any other study through a new lens and purposely disregarding any nation-state national borders, choosing instead to look at these transnational connections—that is going to be a great influence for scholars as we move forward and think about how we want to share this type of information, especially visually.