Eleri Connick

WHAT IF THERE’S GREATER INTIMACY IN THE COLLECTIVE?1

Abstract

In this research note, I track the reflective process of

creating and facilitating a workshop series in Amman, Jordan, as a way

in which to explore the (re)creation, (re)construction, and

(re)negotiation of understandings of Palestinian cultural heritage and

identity. The workshop centers around the idea of materiality from the

Palestinian homes in Amman being framed as a “material witness” of

exile. These material witnesses become an access point into the

individual versus the larger transnational exilic experience. I

introduce the idea of playing within a participatory heritage

framework and how, by starting with the material witnesses from houses

in Amman today, it enables a discussion on the modalities of

exile, local identity formation, and the performativity of memory as

part of an ongoing creative process of meaning-making. I also draw out

discussions of playing with my own methodology practice and what it

means for future research.

خلاصة

في هذه المذكرة البحثية أتتبع العملية التأملية لإنشاء وتسهيل سلسلة ورش عمل في عمان، الأردن، كوسيلة لاستكشاف (إعادة) الإبداع و(إعادة) البناء و(إعادة) التفاوض بشأن تفاهمات تراث وهوية الثقافة الفلسطينية. تتمحور ورشة العمل حول فكرة المادية في البيوت الفلسطينية في عمان التي يتم تأطيرها كـ "شاهد مادي" للمنفى. يصبح هؤلاء الشهود الماديون نقطة وصول إلى الفرد مقابل تجربة المنفى الأكبر عبر الوطنية. أطرح فكرة اللعب ضمن إطار التراث التشاركي وكيف أنه، من خلال البدء بالشهود الماديين من منازل عمان اليوم، يسمح بمناقشة أشكال المنفى، وتشكيل الهوية المحلية، وأداء الذاكرة كجزء من عملية إبداعية مستمرة لصنع المعنى. أقوم أيضًا بإجراء مناقشات حول اللعب من خلال ممارستي المنهجية الخاصة وما .يعنيه بالنسبة للبحث المستقبلي.

For five nights in May 2023, as the world reflected on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Nakba, ten Palestinians in Amman joined me for the workshop series “The Material Witness.” The participants were selected from responses submitted to a general call of interest through the cultural heritage space’s monthly mailing list and social media channels. The call for interest was focused on finding individuals interested in exploring what exile means today in Amman. The inspiration for the workshop series emerged from my doctoral research project which explores the question: What is the role of the house in the creation and performance of “Palestine” among Palestinian exiles living in Jordan and Lebanon? My aim for the workshop series was to use objects from within participants’ homes—referred to as material witnesses of Palestinian exile—to inspire them to narrate their own stories.

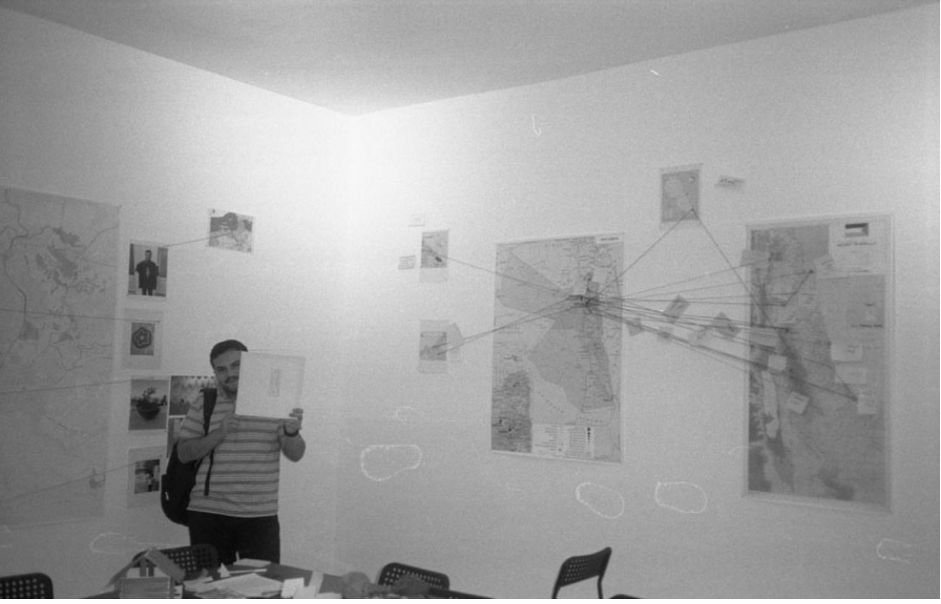

We met in a 25 square meter space which had been turned into a blank canvas for us to mark. It is one of the tiresome parts of the Palestine case that Palestinians must still assert their existence and presence. Therefore, it felt restitutive to physically mark the walls not only with the material witnesses’ journeys of exile but also to trace the development and evolution of our ideas.

The workshop’s methodology could be described as “participatory heritage,” understood as “a space in which individuals engage in cultural activities outside of formal institutions for the purpose of knowledge sharing and co-creating with others.”2 Cocreating with others is an important element here and warrants further exploration. Prior to and throughout the process, I had several concerns. Firstly, would there be engagement? Secondly, how would participants respond to the workshop being conducted predominantly in English rather than completely in Arabic? Thirdly, would I be able to create a space in which ten individuals plus myself could become a collective whereby all felt able to freely contribute?

As a researcher interested in methodology as well as empirical findings, I sought to understand whether a collective setting like the workshop series would prompt a wider space for (re)creation, (re)construction, and (re)negotiation of understandings of Palestinian cultural heritage and identity. It is a constant concern for researchers, particularly when in a setting which is not one’s own—as is the case for a British scholar like myself in Amman—that power dynamics will create research settings where interlocuters will share views of what they imagine the researcher wants to hear. These often become the authorized or official accounts. Yet, such accounts lose the individual, and this workshop was centered on the specific experience of exile in Amman rather than the larger transnational Palestinian story. It was in the first workshop and discussions of what “heritage” means that one participant said, “to play.” She went on to describe that while all others in the room were discussing how it is something to protect and pass down, she felt there is a need to think about how we play with heritage and make it relevant to contemporary Palestine. An initial disruption had taken place—as if the participant had given permission for the others to join her in this “playing.” Or more simply, the participant had elicited the ability for the group to go beyond the authorized accounts.

Our 25 square meter room then became a blank space to tease out these important moments of “playing” and “disrupting” that emerged in response to the historical metanarratives that are most commonly associated with Palestinian heritage and identity, and how Palestinians engage with these narratives on a local level.

The workshop series was also an opportunity for me to play with methodology and to see how the experience generates stories which differ from the more traditional approach of conducting individual interviews across Amman. Furthermore, it was an opportunity to be in a setting which brings about a question of ownership of the research and the dialogue: these are not my stories and never will be. Therefore, I found myself reflecting on the process of working within a cultural heritage space in Amman, so that the findings and stories stay within the city of exile itself.

While the workshops took the Nakba as the starting point of exile, focusing on the objects from houses in Amman today enabled a discussion on the modalities of exile, local identity formation, and the performativity of memory as part of an ongoing creative process of meaning-making. I invoke exile here (and throughout) because I take it to be more powerful in its central reminder of the ongoing nature of the absence from one’s homeland and the political reasons for the absence than, say, a framing such as displacement or dispossession. The nature of exile also implies that this absence does not need to be permanent; instead, this exilic state could end and enable return. By focusing on the individual material witness and all that its story reveals, the object becomes a way in which to expose the everyday inner conflicts that emerge when thinking about one’s Palestinian heritage. It drew to mind Azoulay’s discussion on the discrepancy between how history has been told in official narratives, such as books, versus the history people know and feel.3

The material witnesses that found their way to our 25 square meter blank space were, I believe, illustrations of how the “fixed objects” of Palestinian heritage are shifting or, better still, how collective “symbolic” objects differ from those individuals choose to focus on. Thus, some readers might be surprised that not a single individual brought with them a key—the object for Palestinians in exile.4 However, in our workshop, the room was graced with a travel document from Al-Quds, a sanyit qash (straw tray) from Nablus, and a Gazan clay pot, to name just a few.

Pausing here, it is interesting to zoom into what these material witnesses mean individually and together as a collective in the room. The value of these everyday and ordinary objects transformed during displacement. These objects are now to be held onto and cared for, as they not only reveal a visceral connection to Palestine but also contribute to the oral history of Palestinian exile and form an important contemporary archive of Palestine. They are themselves markers of a “before.” In a twofold effect, they assert a “before” that challenges those who continue to declare Palestine a nation which never existed.5 Furthermore, when these objects are brought together, they commemorate, mourn, and recognize Palestinians’ enduring exile in a way that relinquishes grand narratives to show the multifaceted and heterogenous nature of the Palestinian experience.6 This generation of a heterogeneity of stories cannot be overlooked because while Palestinian identity has become closely intertwined with the seminal event of the Nakba in 1948, Palestinian communities nevertheless have different and unique experiences in exile.7

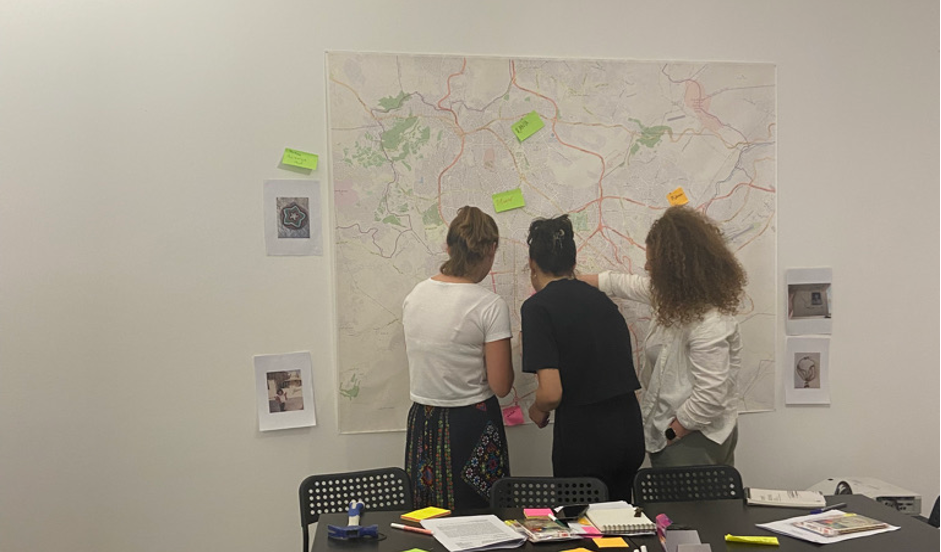

During our second workshop, the group mapped onto the wall both real and imagined journeys of their material witness as a way in which to visualize the displacement of the object. Real journeys were marked in yellow string and understood as journeys that the narrator had been on with the material object; imagined journeys, marked in red string, were defined as those which the narrator knew of its journey through familial stories. The visualization took place across two walls: one wall showcased journeys to Amman while the second wall depicted a map of Amman. This map of Amman offered a way to see in detail where these material witnesses of Palestinian exile now resided within the city.

Staring at the maps of Palestine and Jordan, and the Post-it notes that signaled our need to add maps of Lebanon and the Gulf, one of the participants turned to the group and asked, “Can we add the future to the map?” I silently uttered to myself, “Absolutely!” However, I wanted the decision of this inclusion to come from the group themselves. So concerned with the present, I had not anticipated the future becoming a large conversational point. But this was the entire point of such a workshop series—to disrupt and to play. The suggestion of inclusion of the future seemed to shift the entire dynamic in the room. The energy in the room lifted, and the collective started to postulate about the idea of “What if?” Some of the collective added string back from Amman to where the objects’ stories had begun; others put pins to cities such as Sufud because this particular participant, when exploring Palestine through Google Maps, thought it looked beautiful and somewhere she wanted to explore. Another participant placed a pin in Damascus, not because he had any connection per se but just because he could; if these objects were free to cross any border or boundary, then why not? If they could be anywhere, why could the object not return to a borderless space such as the former Bilad al-Sham? Strikingly, the very interlocutor who asked about inclusion of the future added no pin. For her, the notion of the future was something impossible to comprehend at that moment.

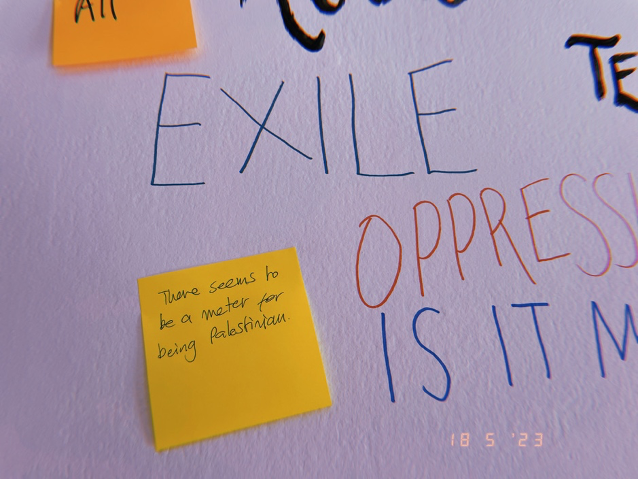

Over the course of the following three nights together, as I watched both from the sidelines as well as actively participated in the discussions, it was as though this participant hoped that by hearing how others postulated the notion of future, she could herself work through her own inner dialogue about what it could mean. Following the session, this participant got in touch to say that she was still not sure how to make sense of her material object’s story because of the ideas that emerged from the exercise, relaying that she felt that her story did not entirely align with the rest of the group. This participant’s idea to “play” with the stories and postulate over the future created a moment to disrupt the well-told stories on familial and national levels. While the objects already provided a more personal opportunity to tell their Palestinian story, the inclusion of the future opened a space for individual creation. Following this, honest discussions emerged where some of the participants noted feelings of “censorship” when thinking about their story of being Palestinian in Amman and in the wider transnational context. “What if I don’t want al-Nakba to be the start of my story?” “What if my desire is to relate to contemporary Palestine rather than al-Nakba solely?” After session four, someone simply wrote on the wall “there seems to be a meter for being Palestinian.”

A dialogue consequently ensued regarding the worries many of the collective had about “being Palestinian enough.” Adamant that “being Palestinian” cannot be linked to suffering, and that it would be dangerous for it to be so, the collective brought to the forefront one of the continuous internal conflicts of being Palestinian. Such honest conversations demonstrated the “huge sense of fear” in questioning the dominant thinking surrounding Palestinian identity. It was at this moment that I realized the poignancy of these discussions happening in the collective setting. An intimacy had emerged which allowed for questions and commentary on the confusion related to being Palestinian in Amman: the uniqueness of this particular cityscape, its history with Palestine and Palestinians, and, despite geographic closeness to Palestine, the vast distance that has emerged between individuals on being Palestinian in Amman.

Mohammed El-Kurd, a poet and cultural practitioner, recently wrote an extended piece on “What Role Does Culture Play in Palestinian Liberation?” drawing on themes of guilt and obligation. When writing this piece, I was drawn to something El-Kurd noted his friend said: “Artists are more effective when they tackle individualized narratives rather than what he called ‘the abstracted slogans of the cause.’”9 The group could speak well to the history of Palestine, the terrors of 1948, and the ongoing settler occupation and violence that has plagued Palestine for over seventy-five years. However, there was a sense in which guilt was felt in thinking about one’s own story, one’s own confusion about identity and heritage because of the “Palestinian meter.” Yet when these stories began to surface, the real impact and power of stories in understanding exile in specific cityscapes emerged. Stories which, I think, only came to the surface because the group realized each of them had their own confusion regarding these very questions. This group setting, coupled with using the material witnesses as a way of thinking about one’s identity and heritage, became an opener to revealing these questions. Thus, while all the questions were not answered, maybe it was more powerful that these internalized questions had entered the room. Pausing here, I believe this is something to ponder further. In this case, I felt as though the power of the workshop was felt in the way in which the “participatory heritage” framing allowed for codismantling and corupturing of the meta-narratives by the space in which to pose questions.

This workshop’s aim was to methodologically play and challenge my own theoretical grounding, while bringing a collective together who in turn brought an object from their home through which to think about their own heritage. Yet, in a post-workshop follow-up conversation with one of the participants, I saw the way in which the workshop had caused disruption. Disruption in the sense in which it can add depth, nuance, and complexity by causing an interruption to one’s foundation—such as bringing a new layer to one’s thinking. Sitting with her iced tea, one participant told me how, in the aftermath of the workshop, she felt more Palestinian than before; she felt free from thinking that her Palestinian identity had to be connected to the famous Palestinian stories. Now, she understood her story in minute detail. There was a sense in which she described an emancipation from the dominant cultural production of Palestine, which is so prominent but does not reflect her own cultural heritage.

As this research moves forward—despite it seeming slightly “oxymoronic” that the collective might be a space more open (and intimate) to individual stories—I will be thinking about how, when engaging with these material witnesses in such a setting, these objects become part of an extended archive of Palestine. Moreover, from these discussions, space emerges in which alternative dynamics (and questioning) of Palestinian heritage and memory-making, identity, and social forgetting of the past can be (re)constructed and (re)negotiated.