Linda K. Jacobs

“PLAYING EAST”: ARABS PLAY ARABS IN NINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICA

Abstract

This article explores the practice, widespread among the diasporic Syrians and North Africans of the nineteenth century, of pretending to be Arabs. “Arabs” were astute purveyors of Orientalism, both in entertainment and in trade. Syrian peddlers and merchants played the Orientalist card because they knew it would help sell their goods. In this paper, I concentrate on those Arabs who made a living entertaining Americans in the nineteenth century by dressing up. Entertainment ran the gamut from stage performance like vaudeville and circus acts to high-toned lectures, with the former being dominated by North Africans and the latter by Syrian Christians. Orientalism sold, and every Arab knew it and exploited it.

INTRODUCTION

This paper explores the practice, widespread among the diasporic Syrians and North Africans of the nineteenth century, of pretending to be Arabs. I use the terms “pretending” and “Arabs” advisedly, because the Syrian Christians who entertained were fully aware of the irony of dressing up as Bedouins and performing “Mohammedan” prayers and weddings, and the North Africans on the vaudeville circuit were seasoned performers who knew how to use their exoticism to please American audiences.

Arabs were astute purveyors of Orientalism, both in entertainment and in trade—and in a sense the two professions had much in common. Syrian peddlers and merchants played the Orientalist card because they knew it would help sell their goods: they used Orientalist motifs in their advertisements, displayed Oriental goods in their stores, even when they were really selling notions, and spun stories of the exotic east when called upon (Figures 1 and 2). If tourists visited the Syrian Quarter in New York to gawk at the exotic “other,” all the better for business. A woman peddler was quoted as saying, “I wear my kerchief because it is good for business. . . . If I dressed like an American lady, no one would notice me.”1

In this paper, however, I concentrate on those Arabs who made a living entertaining Americans in the nineteenth century, whether on the vaudeville stage, in the church hall or in the homes of the wealthy. The more flamboyant arenas were mostly dominated by North Africans, while the refined venues were monopolized by Syrian Christians (primarily Protestants and Orthodox). The difference between them was a matter of degree rather than kind, and the same people moved from one kind of act to another, often within the same performance. To the Syrian Christian, Orientalism usually meant posing as an “Arab” (as opposed to Syrian, a distinction the Syrians made themselves) and “Arab” usually meant “Moslem.” The North Africans, who were presumably Muslims, exploited their origins and exoticism to the fullest. Orientalism sold, and every Arab knew it.

NORTH AFRICANS IN CIRCUSES AND VAUDEVILLE

Arabs began performing in this country in the 1860s. The first group to arrive was the Ali Ben Abdallah Troupe, landing in New York in August of 1863. They must have been under contract, because within a week a tent was erected across from the Brooklyn Academy of Music and named “The Alhambra Pavilion of the Children of the Desert.” The Arabs were described as ”the only band of pure Bedouins who have ever visited America.”2 The all-male troupe exhibited feats of strength, swordplay (and a Bridge of Bayonets), gymnastic feats, and equestrian stunts. They traveled for more than a decade, and went as far west as Ohio, performing in theaters or under circus tents.

Organized circuses began to include Arabs as “ethnological types” around 1881. P.T. Barnum advertised a show by “Syrian” performers in New York in 1884, in “the greatest assembly of curious human beings ever seen together on earth,” but these were probably mostly if not all, North Africans.3 In 1885 Arabs appeared again for Barnum in a “Vast Ethnological Congress of Strange and Heathen Tribes,”4 and in 1886 Barnum presented a troupe of “Arabians.” In none of these announcements was it specified what exactly these Arabs did. But we know that at least one of these groups was a Moroccan troupe under the management of Abdallah Ben Said; when they performed in Barnum’s circus at Madison Square Garden in 1886, their athletic achievements “evoked much applause.”5 Although they were advertised as “Arabs” and part of the great ethnological congress, the troupe mostly performed as acrobats and gunslingers. Ben Said was once accidentally shot when practicing sharp shooting for the Buffalo Bill show. The equivalence of the Wild West with the Wild East was not accidental—many of the acts were identical and only distinguished by the costumes—and later shows organized by the Moroccan Hajji Tahar were pointedly called Wild East Shows.

Tony Pastor’s Theater on 14th Street in New York advertised “The Whirlwinds of the Desert, just arrived from Cairo, Egypt. Hadj Tahar and Hassin Ben Ali with their troupe of 20 genuine Moorish and Bedouin Arabs in a realistic picture of the East: A Moorish School in Suez [Sus], Africa, introducing Moorish Customs, Sports, Games, Dances and Wonderful Tumbling, Leaps, Vaulting, Musket Drill.”6 These men again were not from Egypt but from Tunisia or Morocco, but none cared how they were advertised, as long as they brought in the crowds. In this example, dating from 1890, the mix of acrobatics, gun slinging, and “Moorish customs” begins to blur the line between pure circus entertainment and the addition of pseudo-ethnographic content so prevalent in later world’s fairs.

A short eleven-second film made by Thomas Edison in 1894 in his New Jersey Black Mariah studio shows Hadji Cheriff, another well-known Moroccan performer and impresario, performing acrobatics, leaping and bounding around the stage. If it were not for the exotic clothes, he could be any nineteenth-century acrobat.7

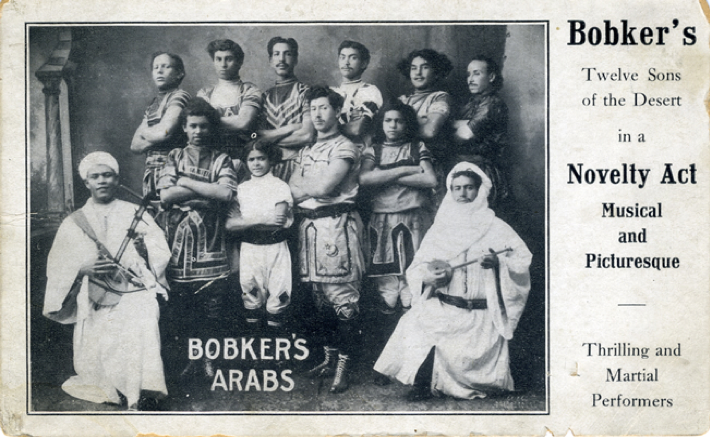

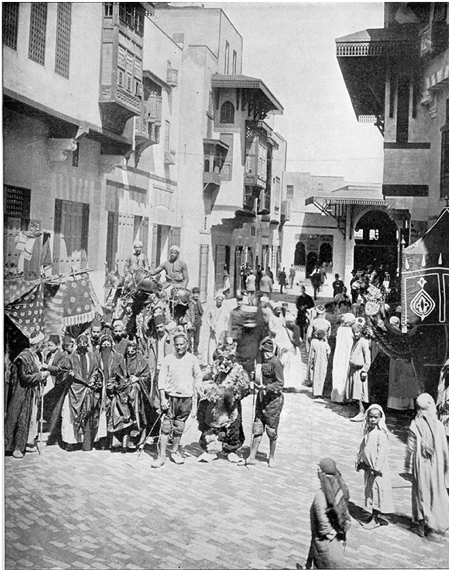

Those North African entertainers who had already been performing in Wild West shows discovered that exoticism sold; they went on to dominate the world of Oriental entertainment on stages in the United States and Europe. The demand for them was almost continuous over the final decade of the nineteenth century; they showed up in Wild West shows, circuses, minstrel shows, vaudeville acts, world’s fairs, and finally the amusement parks that sprang up all over the country after the Chicago Columbian fair of 1893. There were probably no more than about fifty North Africans in this country at any one time performing in these venues, but they were ubiquitous. Many of them listed their profession as “acrobat,” “showman,” “performer,” “actor,” and “camel rider” on various documents. The nature of their work demanded that they be on the road constantly, but New York, as it does today, boasted a huge number of theaters, which induced several of the companies to make New York their base (Figure 3).

The editor of Kawkab America, the first Arabic newspaper printed in the United States, had this to say about these Arab troupes: “There are several supposed, or so called Arab troupes travelling in this country; but, we know only of two who could lay claim to being genuine, Sie Hassan Ben Ali’s and that of Hajji Tahar Ben Mohammed. . .”8 That Nageeb Arbeely vouched for these two troupes speaks more to the fact that he did business with both of them than to their authenticity.

A few Syrians also worked in these traveling shows. Elias Zreik, a New York Syrian, was said to have been a “strong man” in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show—he was almost seven feet tall and was supposedly nicknamed “Big Mike” by some of the other Syrians of the Colony. He began to build his image as soon as he arrived in New York. A full-page illustrated article entitled, “NEW YORK SYRIAN WHO KILLED 200 TURKS,” detailed his heroic exploits, calling him the “Giant of Lebanon.” It seems he defended his village single-handedly from a horde of well-armed Turks. A portrait of Zreik in an oval frame in the article shows him sitting in a chair with a rifle propped by his side, wearing a Greek-style beret, and sporting a very large bushy moustache. A sketch in the same article shows him shooting sword-bearing Turks while a pretty young girl runs away.9 After his stint with Buffalo Bill, he had a checkered career as a butcher, a camel driver in Coney Island and a coffee merchant. He was involved in numerous brawls with his Irish neighbors on Washington Street, often ending up in jail. Most spectacularly, he faced charges of murdering a fellow Syrian in 1906 but was acquitted.

Lotfallah Atta, before he became a restaurant owner in New York’s Syrian Colony, spent four years in Nashville, Tennessee, the base from which he traveled with the Buffalo Bill show. He performed as a strong man, supposedly lifting twelve men over his head night after night. A Buffalo Bill advertising card from this period shows a group of Arabs forming a human tree of ten men and boys; the man at the bottom, holding everything together, must have been someone like Atta. Both of these Syrians, however, settled down to other jobs late in the nineteenth century, while the North Africans continued to play on vaudeville stages well into the twentieth.

ENTERTAINERS AT THE COLUMBIAN FAIR

Many Middle Eastern performers who were already in the United States participated in the Columbian fair of 1893, but hundreds, if not thousands, more arrived to take part in the fair. Two ships—the Guildhall (from Alexandria) and the Cynthiana (from Beirut)—arrived in New York harbor within two weeks of each other filled with people, animals, costumes, props, building material, and goods bound for the fair. One hundred and seventy-five Egyptians landed at New York on April 11, 1893, from the Guildhall. The manager of the Egyptian enterprise, George Pangalo, accompanied them. Pangalo had been a banker in Alexandria, among other careers, and was said to be the one who took inspiration from the Paris fair’s “Rue du Caire,” to build The Street of Cairo (which came to be called simply “Cairo Street”) in Chicago. The Cynthiana brought 275 participants, most of whom were members of the Hamidie Company, formed in Constantinople to represent the Ottoman Empire at the fair (and named for the sultan). The Hamidie Company was the largest Middle Eastern presence at the fair, owning the Turkish Pavilion inside the fair proper as well as the Turkish Village on the Midway Plaisance. The company was managed by a group of six Syrians, who were also investors alongside the sultan himself.

Every participant was in the entertainment business at the fair, whether by simply having to dress up in “native costume” as they went about their work, serving in the Turkish coffee houses, acting as a donkey boy or camel driver on the Street of Cairo, or actually performing in the reenactments, pageants and theaters. Syrian merchants set up shops in the replicas of a Cairo street, a Tunisian village, or the Alhambra, and they too had to be “in character.” Twice a day a Muslim wedding procession was reenacted on Cairo Street; North Africans or Syrians would demonstrate sword fighting; “Sheikh Barakat” told fortunes for fifteen cents; customers could ride camels or donkeys up and down Cairo Street or sit in a Turkish coffee shop and smoke a narghile, while an Oriental confectioner cried “Hot, hot!” to advertise his fresh pastries. Most temptingly, one could see belly dancers in the Turkish Theater for the admission price of fifty cents. All of these customers could and did buy Oriental or Holy Land goods from the dozens of Syrian merchants who set up concessions at every Middle Eastern venue at the fair. Orientalism was immensely popular and profitable.

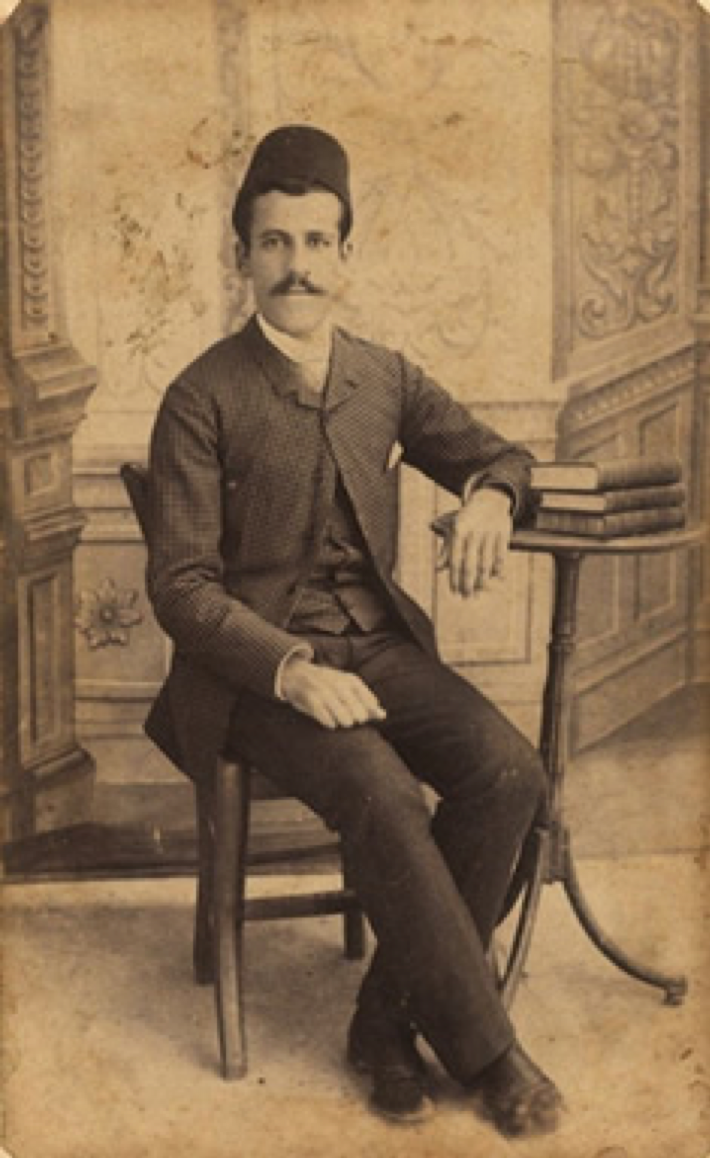

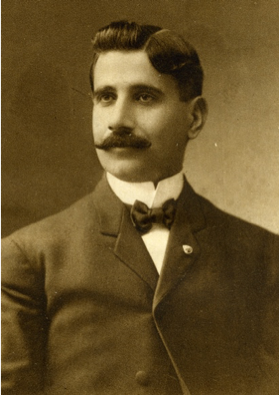

Bedouins, Turks, Moors, and Egyptians filled the pages of the illustrated supplements and photography books that documented the fair. There was easily ten times the number of photographs of Middle Easterners than any other national or ethnic group. Syrians, however, were the exception: they were rarely photographed as Syrians, apparently because they were simply not exotic enough. The majority of Syrians who attended the fair were not performing but managing the concessions, whether they were working in the North African, Egyptian, Turkish or Persian venues. We do know however, that when called upon the Syrians could and did dress up. Two photographs of cousins and near-contemporaries in Beirut (Figures 4 and 5) show David Fuleihan dressed as any educated young Syrian man would dress and Naoum Fuleihan dressed up for the fair. In a clichéd conceit, Figure 6 contrasts “Europeanized Turks” (Syrians) with “Asiatic Turks” (Arabs), but all of these men were Syrian, and one can find them in other photographs dressed as different “types.” The Europeanized Turks were generally not worth photographing.

The entertainment provided by the Hamidie Company at the fair was more ethnographic than entertaining: traditional music accompanied traditional dancers; Turkish actors performed plays in Turkish, and a myriad of ethnographic/educational objects were on display. Each member of the company wore a star and crescent emblazoned on his costume (as can be seen on one of the “Asiatic Turks” in Figure 6).

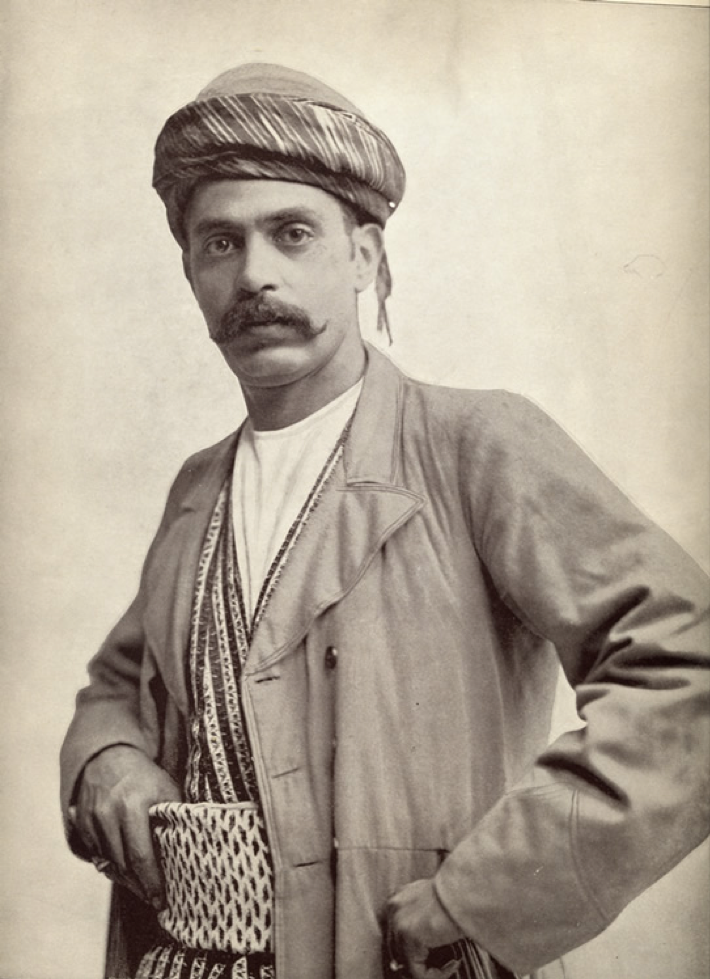

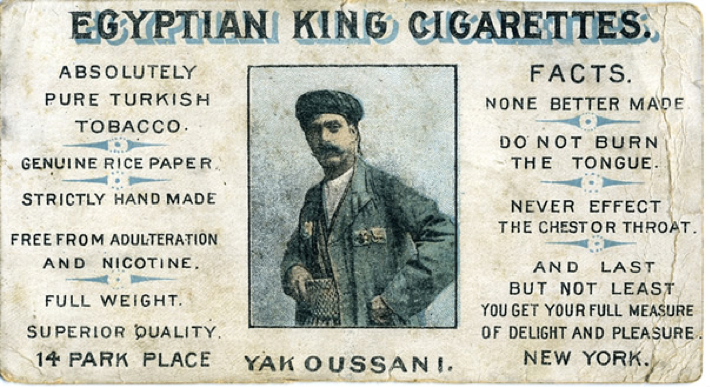

The Oussani brothers, who were Chaldeans from Baghdad, came to the fair under contract to a Syrian company formed especially to do business at the fair. The brothers, who had been in the import-export trade between Persia and Baghdad, went to the fair to set up the Persian Palace, as well as to sell goods from Persia and Baghdad (Figure 1). When the Persian Palace failed to attract the custom they had counted on, they imported dancing girls from Paris to liven up the show. By some accounts, the name of the venue became known as the “Persian Palace of Eros.” They were trying to compete with the great sensation of the Chicago fair: the belly dancers.

BELLY DANCERS AT THE COLUMBIAN FAIR AND AFTER

The Street of Cairo (Figure 7) was far and away the biggest moneymaker at the fair (possibly saving the fair from bankruptcy), and belly dancing was the Street’s premier attraction. Belly dancing was possibly first seen in the United States at the 1876 Centennial in Philadelphia, when a Tunisian merchant, M. Valenti, set up a Tunisian café in which there was entertainment. At L’Exposition Universelle in Paris of 1889, belly dancing (“la danse du ventre”) was a major attraction,10 and by the time of the Chicago fair, entrepreneurs knew that this would be a goldmine.

The passengers on the Guildhall included eleven “dancing girls.” One of them was called upon to give a sample of her act to a group of tourists gathered on the New York dock. Nageeb Arbeely was there and praised the performance in the pages of his newspaper, Kawkab America:

Her ‘Danse Du Ventre,’ as the name implies, consisted in the measured movements of the stomach, shoulders and loins in accompaniment with the music, with hardly any noticeable movements of the feet. The body swayed gently to and fro, the eyes changed their expressions with almost each movement, the dancer advanced in measured steps while various parts of her body were kept in shivering-like motions independent from each other. She held two handkerchiefs that she used to emphasize the harmonious and undulating movements of her body.11

This was no doubt the first and last time the words “belly dancing” and “measured” appeared in the same sentence.

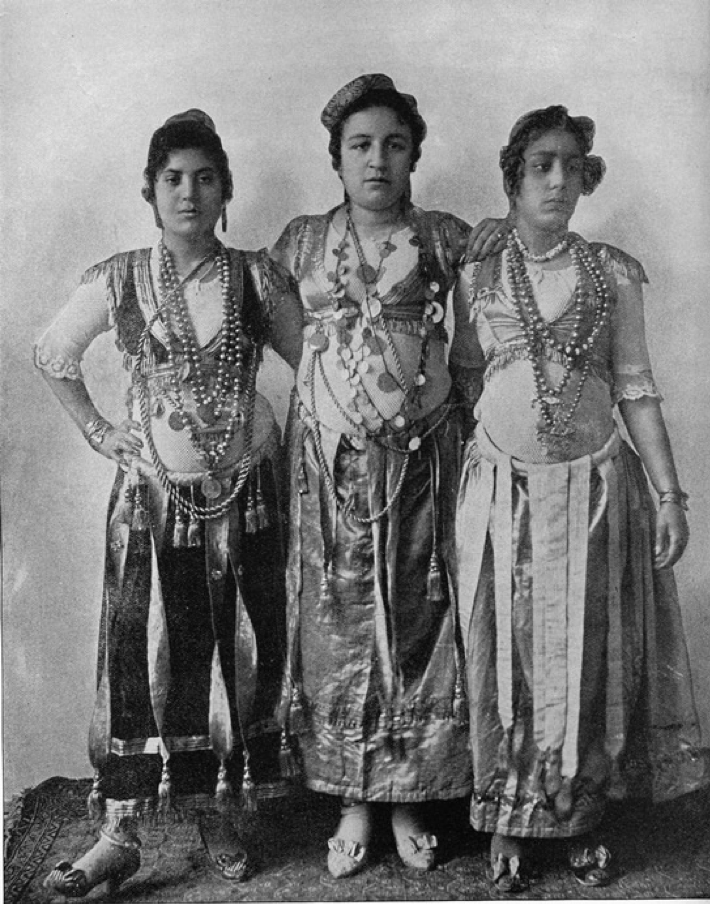

Despite a supplementary admission charge of fifty cents, lines formed to get into the venues where belly dancing was performed. If one can judge from the photographs, the Egyptian dancers were more daringly clothed than the North Africans or Syrians (Figures 8, 9 and 10), with only netting covering their torso. That fact and the perceived eroticism of the dance ensured their popularity. Well-publicized debates about the propriety of the entertainment ensured larger and larger crowds. When the dance venues were closed on Sundays to assuage the protests of the “morality police,” admission fees to the fair halved. They were quickly allowed to reopen. When Nageeb Arbeely was asked his opinion about the morality of the dancers, he equivocated, saying that although they showed more flesh and danced more erotically than they would at home, they should not be shut down.12 In this, he was not defending the propriety of the dance as much as protecting the Syrian businessmen at the fair, knowing how important the dancers were to the merchants’ success. The Syrian merchants undoubtedly benefitted from the huge audiences generated by the belly dancing, since they ran the concessions in the Street of Cairo as everywhere else. At the same time, they tried to distance themselves from the seedier aspects of this entertainment, claiming that the dancers were Egyptian, not Syrian, although there were Syrian, Egyptian, and North African dancers performing. The Egyptians, however, seemed to have cornered the erotic market, at least by the lights of the American audience. This was why they drew the crowds to Cairo Street.

The dancers earned 500 dollars for their six-month stint in Chicago (a large sum in 1893, even by American standards); the Street of Cairo reportedly brought in 2,000 dollars a day. It was said that the dancers saved the Street of Cairo, and the Street of Cairo saved the fair. By contrast, the Hamidie Company, whose displays were more educational and high-minded, went bankrupt, leaving its actors, animals, and equipment stranded in Chicago.

As soon as the Fair closed (in November of 1893), Oriental dancers began to appear all over the country; “Little Egypts” danced the “coochee coochee” from Omaha, Nebraska, to San Jose, California. One newspaper reporter at least recognized the paradox of the scores of Little Egypts: “If the New York girl is Little Egypt, who the dickens is the little woman who has been drinking wine in Butte?”13 It is clear that from this very early moment, American women began to coopt belly dancing; if one digs beneath the exotic costumes and the Oriental names, one often finds an American. The semi-nudity that was seen for the first time at the Chicago fair became more common and more daring as American women took the place of the Middle Eastern dancers.

There were, however, some Middle Eastern women who continued to dance, some under their own management but most under the management of (male) Arab or American managers or agents. New York was the center for belly dancing in the nineteenth century, with its numerous theaters, Turkish cafés, and Coney Island. The most famous of the “Little Egypts,” Ashea Wahby, was said to be earning 1,000 dollars a week at Oscar Hammerstein’s theater.14 The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice was all over these dancers, focusing on two aspects of the performance: their clothing (or lack thereof) and their movements. Theaters where belly dancers performed were regularly raided by the police, and the impresario and the “girls” were taken to trial, where the judges paid close attention to the titillating descriptions of the clothing the women wore and the movements they made. They were usually bailed out immediately by their managers and released under the condition that they modify the dance or the costume, or both. When they complied, by covering more fully or modifying their movements, the audience often booed or walked out.

There are several short Edison films from the late nineteenth century of belly dancers, all on YouTube. Five different women appear, of whom three could be Middle Eastern. One in particular is striking for her modest clothing, her subdued style, and her accompanists, who are clearly North African. One of the films has been censored with a double white picket fence painted over the dancer’s moving torso and hips. Perhaps this film was the one shown on an Edison Kinetoscope at Coney Island, which was a huge hit until the police closed it down.15

NORTH AFRICAN IMPRESARIOS

North Africans were successful managers and impresarios; they hired their own performers, often bringing them from abroad, found them housing, trained them, and fired them when they were no longer useful. Some impresarios would hire an American agent to book them into a theater, and others dealt directly with theater owners, such as the minstrel-show magnate, Al G. Field. Their acts were of two kinds: they either performed generic circus acts, with strong men, acrobats and jugglers as described above, or performed “Customs of the Orient” acts, such as weddings, sword fights, or Muslims in prayer, and they often combined the two in one performance. The former type lasted well into the twentieth century, while the latter faded from view earlier, as Orientalism lost its allure.

Of these managers, four were particularly successful: Abdallah Ben Said, Hajji Tahar, Hassan Ben Ali, and Hajji Cheriff. All started out as performer-managers and then became full time manager-impresarios. Abdallah Ben Said came to the United States in 1883, with a “Red Sea Circus of Male and Female Weird Bedouin Performers,”16 which traveled around the country with the W.W. Cole and P.T. Barnum circuses. They were a troupe of twelve men and one woman (Ben Said’s wife). They showed feats of strength, a human pyramid, knife throwing, acrobatics, and sword fighting. By the mid 1890s, they were employed at the new amusement park at Coney Island in the “Streets of Cairo,” an attraction modeled closely on the one of similar name at the Columbian Fair. The troupe by then had a much more Orientalist cast, consisting of musicians, dancers, camel drivers, and “Nubian giants.” Each winter, when the performers (men and women) were furloughed, they were forced to live hand to mouth in the abandoned unheated theater in Coney Island, while Ben Said lived in comfort elsewhere.

Hajji Tahar was the most visible and well known of the managers. He came to this country in 1883 with the troupe of “Bedouin Arabs” led by Abdallah Ben Said. Tahar married twice (both Americans) and had a child by each wife. Neither marriage nor children kept him at home, however; he and his troupe performed all over the United States and Europe, and when they were in New York, he and they lived on 8th Avenue at 15th Street, while his wife and child were installed in an apartment building nearby. His troupe was international and included Filipinos, Americans, Englishmen and North Africans, all with exotic stage names that were meant to sound foreign if not precisely Arab. Tahar was involved in two court cases, in which he and another Moroccan manager were implicated in the indenturing or coercive retention of young performers. Since the cases did not address the coercion issue directly, it is impossible to know whether this was a common practice, or even whether it was truly coercive, but these cases and a few other examples suggest that these troupes included children who were not there of their own volition. This practice was not of course exclusive to Arabs but common in many nineteenth-century vaudeville acts, as we know that many early movie actors learned their trade as child performers on vaudeville stages.

An entertainer from Morocco, Hassan Ben Ali, who had been performing around the United States in the 1880s, returned to Morocco in late 1891 to gather together a group of Moroccan “dwarfs” to show at the Chicago fair;17 he also tried to bring back a complete Moroccan village to reconstruct in Chicago. He was in partnership with Nageeb Arbeely, the editor of Kawkab America. Before the fair, the troupe he brought back performed at various venues, such as the “wedding” described below. At the fair itself, he presented a reenactment of the violent capture of Africans by Arab slavers. Later his twelve-member “Royal Moorish Troupe” performed in New York theaters, presenting acrobats, contortionists and gun spinners.18 One of his acrobats was a Mrs. Masouda Ben Hadji, whose face “betokened Hibernian rather than Oriental origin.”19 In advertisements, he advised that he dealt directly with theater owners himself, avoiding agents. His company, which he renamed “Hassan Ben Ali Arabs Co.,” moved to Coney Island around 1900 and continued to play on vaudeville stages well into the twentieth century, even surviving Ben Ali’s death in 1914.

Hajji Cheriff also came to the United States in 1883, perhaps with Abdallah Ben Said. He performed in vaudeville and minstrel shows, juggling a thirty-five-pound rifle, and then joined Hassan Ben Ali’s troupe, traveling with the Wild West shows and Barnum & Bailey’s Circus. It is he who is shown in Edison’s film, cited above, leaping and bounding on the stage of Edison’s studio. Cheriff’s wife, Henrietta, who was an American, claimed to have made the pilgrimage to Mecca after converting to Islam. She dressed up like a Moorish woman and performed as an Arab, an early example of American cooptation of “Oriental” performance. By the end of the century, he managed his own group, which performed with Al G. Field’s minstrel shows, calling themselves “A Tribe of Genuine Mamelukes.”

SYRIAN IMPRESARIOS

Most of the Syrians who became impresarios of Middle Eastern acts learned the ropes at the Chicago fair. Elias M. Malluk was an exception, bringing over a group of thirteen Turkish “howling dervishes” and thirteen Egyptian jugglers in 1892. He soon abandoned his charges to the streets of New York and set himself up as a dry goods merchant. The performers brought suit against him and thought to strengthen their case by appearing in court dressed in their native finery; the judge was not impressed and dismissed the case. The poor entertainers were left to find their own way home.

George Jabour, who hailed from Constantinople and who came for the fair, became one of the most conspicuous figures at the new amusement park at Coney Island, owning both the Turkish Theater and a Turkish Smoking Parlor on Tilyou’s Walk. “Fatima” danced the “coochee coochee” in his theater. Whether Fatima was a Syrian, or even a Middle Eastern woman, is impossible to know, although in one newspaper article, she is referred to as Jabour’s wife. When the dancers and Jabour were put on trial for presenting obscene entertainment, the judge threatened to shut down both Jabour’s venues. He said, “I think he [Jabour] has been running an indecent and immoral show. . .”20 Jabour then asked if he could present “living pictures,” dancers posed in flesh-colored body stockings. The judge became even more livid, and said if he did, “I will close your show without a moment’s notice.”21 Undeterred, in 1899, Jabour opened another venue called the “Kairo Café” in Brooklyn and announced there would be Oriental beauties presented there. This announcement was a red flag to the police, who allowed him to open but warned him they would be watching him.

The shows that Jabour built at Coney Island soon morphed into the traveling Jabour Carnival and Circus Company, featuring a Ferris Wheel (a contraption which debuted at the Chicago fair), a loop-the-loop, and its most popular attraction, “Moorish dancing girls.” After the dancing girls, “Fatima,” the trained bear, did her turn.22 The circus traveled all over the United States from 1901 to at least 1904, but Jabour declared personal bankruptcy in 1903, with liabilities of $87,000 and no assets.23

In August of 1893, Marie Hazaby (Halaby?) brought over four women belly dancers who were headed for the Columbian fair. Whether she was their manager or simply shepherding them to the fair is unclear. At first the group was denied entry at the Port of New York, the immigration authorities insisting the dancers had come for immoral purposes. The contrast between their reception and that of the dancers who had come the previous April is striking. In four months, the attitude had changed from fascination to revulsion. Clever Marie, however, claimed the women were Greek artists from a theater in Constantinople, and all were admitted.24

ARABS PRESENT “THE MOSLEM WAY OF LIFE”

The Orientalist fad of the late nineteenth century gave rise to a hunger among Americans for knowledge of the Middle East. All of the Middle Eastern installations at the various world’s fairs were a mixture of ethnographic display, patriotic bombast, commerce, and exoticism. The Philadelphia fair in 1876 represented the first large-scale appearance of Middle Eastern entertainment in the United States, apart from the North African circus troupe described above. Not long after that fair, a certain Professor James Rosedale of Jerusalem began to perform costumed tableaux of the Bible Lands in churches around the United States. In 1880, he brought over a group of Arabs, “the only Palestine Arabs who ever left their native land,” in order to be able to illustrate more completely these Bible stories. The group checked into their hotel in full native regalia. They traveled all over the country, offering the public “living illustrations of life in the Orient,”25 including a Bedouin wedding ceremony, a “native” feast, a highway robbery, a Mohammedan at prayer, and a Turkish court scene in which the judges were both bribed. The Biblical tableaux had vanished. A reporter was convinced “they portray truthfully the remarkable customs of their country. . .”26 Admission was fifty cents.

A group of Moroccan entertainers performed a “Moroccan wedding” at New York’s Park Theater in 1893. The groom was “Abd-el Hassan” and the bride was “Lala Ro-Kia,” a name borrowed from Thomas Moore’s Orientalist fantasy of 1817. The performer/manager Hassan Ben Ali officiated at this “wedding.” The performers included a Bedouin, Moors with red tunics, a singer and poet from Tangier, and Moorish officers. All of these players were headed to the Columbian fair. Despite the obviously staged performance (after all, it was in a theater), the reporter believed the wedding was genuine; he credulously reported exactly what Ben Ali had told him: that the couple had been married in a civil ceremony previously but had decided it was not of sufficient grandeur to celebrate their union, so they were having another ceremony, this time in front of an audience.

Joseph Oussani and Yak Oussani, the two Chaldean brothers from Iraq who built the Persian Palace at the Chicago fair, opened a Turkish smoking parlor on West 29th Street in 1894. The café was meant to complement their tobacco business by explicitly trying to make smoking in public acceptable, and even fashionable, for women. Joseph took sole control when Yak decided to concentrate on the tobacco business. The Cairo Café as it was called (bringing the Chicago fair’s Cairo Street to the mind of the public) served Turkish coffee and offered the customers narghiles, chibouks and cigarettes made with the Oussanis’ Turkish tobacco. Apparently the café also sold liquor without a license. The place was decorated with divans on which the customers lounged, as well as other Orientalia, and the bouncer was dressed as a Bedouin. In Victorian America, the place was unique and rather daring: imagine women lounging in public, smoking! It became a phenomenon and a big money maker, attracting the “swells” who came not only to smoke but to drink.

Oussani soon opened a second place called The Chibouk around the corner from the Cairo Café. There were frequent fights reported at both venues, both among the drunken clientele and between the customers and management. There were accusations that Oussani was selling hashish as well as tobacco. Both places were raided frequently by the police, not just for serving liquor without a license, but reportedly for being brothels. Judging by the ages of the “girls” who were arrested with the owners, the accusation may have been true. Oussani and his wife ended up in jail on more than one occasion but always managed to pay whatever fine was imposed. It has been reported that by the turn of the century there were five hundred Turkish smoking parlors in New York; whatever the truth of the number, all were modeled on Oussani’s. Several Syrian-owned Turkish smoking parlors opened in Coney Island in imitation of the Cairo Café, and several of them may have been brothels as well. The cafés were themselves theater sets for the Orientalist performance undertaken by the owner and staff of these establishments.

In 1897, a “Moslem wedding” took place at the Cairo Café. One “Moulla Hashem” united “Ayesha” and “Mohammet Ali” in matrimony. “When Oussani, the proprietor of the place, was asked whether it was a genuine [wedding], he swore by the beard of the Prophet that it was as genuine as they have anywhere.”27 Of course, Oussani was a Christian, so swearing by the “beard of the Prophet” probably did not mean much to him.

These reenactments, although giving off a whiff of farce, may have been taken seriously by the American clientele. At the very least, they paid to be entertained. Syrians and North Africans well knew this, and these “educational” entertainments proliferated all over the country in the last decade of the nineteenth century.

SYRIAN MEN ON THE LECTURE CIRCUIT

Much more refined than these Oriental entertainments that purported to show “Life in the Moslem East,” but of a piece with them, were the high-minded lectures about the Holy Land or the Arab East given by Orthodox and Protestant Syrian immigrants (both men and women) all over the country. This practice followed a long tradition of American missionaries who would come back from their time abroad and give lectures about Life in the East, as well as James Rosedale’s show of “native Arabs.” But now the Syrians themselves were doing it, and it was one of the most common ways for Syrians to earn extra money. These lecturers were self-taught, self-motivated, and self-employed.

Some of them used a church as their entrée, some used connections to prominent residents of a town, but all sought to project the highest respectability and refinement. To bring in funds, they either charged admission or brought along Oriental goods to sell at the end of the lecture or performance. These performances were invariably couched in the language of Christian endeavor, either by calling the lecturer a new convert, a missionary, or a representative of some worthy Christian cause in the Middle East.

Beginning in 1881, less than three years after they arrived, Yusef Arbeely and his sons (reputed to be the first Syrian family to immigrate to the United States) traveled around the country giving talks on the customs of the Orient. At first the lectures were similar to those lectures given by returning missionaries: they were serious and earnest, aimed at educating the audience about the Holy Land. But soon they became more entertaining than educational, although they were still expected to have a gloss of ethnographic authenticity, which was later cultivated to such marvelous effect at the Chicago fair. The Syrian lecturers exploited the exotic, something they had in common with their vaudeville brothers and belly-dancing sisters.

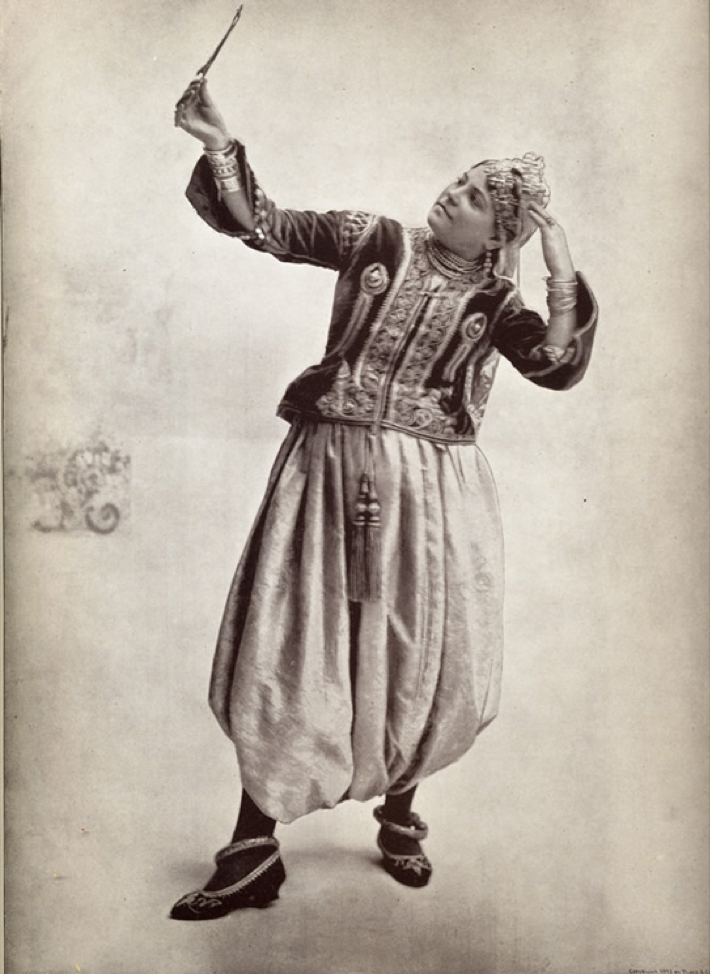

At an event in Washington, D.C., put on by the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society, for example, the Arbeely father and sons presented “An Evening in the Holy Land” with swordplay and a Muslim wedding. The sons traveled on their own as well, playing musical instruments, smoking the narghile, and even dressing up as females and dancing (Figures 11–13). Typically, the event was advertised as both a “Missionary Reception and Mohammodan [sic] Sword Exercise.” Admission was 25 cents.

With years of performance under his belt from traveling with his father and brothers, Nageeb Arbeely, by then the editor of Kawkab America, was much in demand in the nineties to give lectures and demonstrations of Arab customs. In 1893, he reportedly brought one hundred Syrians to perform in front of 15,000 Shriners at Madison Square Garden (both numbers surely exaggerated). The Syrians imitated “howling dervishes,” demonstrated a “skirt dance” and showed a “Moslem’s preparation for prayer.” He made gentle fun of his audience (which included the mayor of New York and other luminaries), by saying, “red fezzes [worn by the Shriners] were as perplexing to the Orientals on the platform as the costumes of these were interesting and novel to those whom they faced.”28

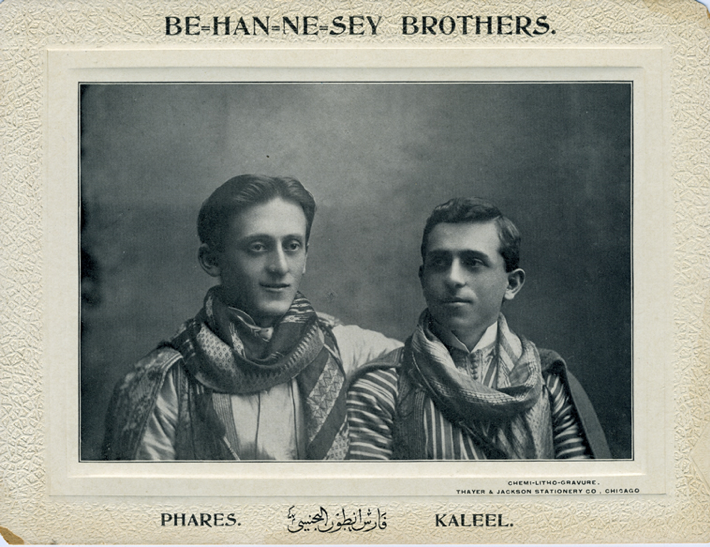

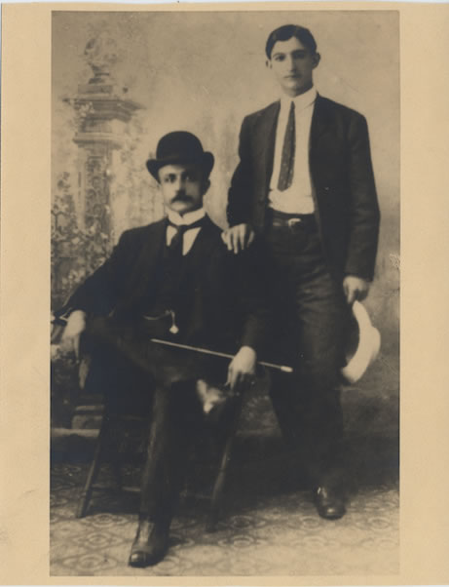

Several members of the Presbyterian Moghabghab family from Ain Zehalta joined the lecture circuit in the nineteenth century. Two Moghabghab brothers, Kaleel and Saleem, came to the United States in 1888 and 1890, respectively, and married two Moutran sisters from Zahleh in 1890. The couples travelled around the country giving talks in native costume about the progress of Christianity in Syria.29 Kaleel died in Colorado in 1892, but Saleem and his wife Nabeeha, styling themselves “native missionaries,” continued to performed at churches. He lectured and she modeled the “costumes of the Druses and Mohammedans.”30 Instead of charging admission, they sold goods. They made several countrywide circuits, performing wherever they found a suitable venue. Finally returning to live in Atlantic City, he opened an Oriental and dry goods business with two other brothers, while she became a well-known women’s fashion retailer with stores in Miami, Atlantic City, and New Hampshire.

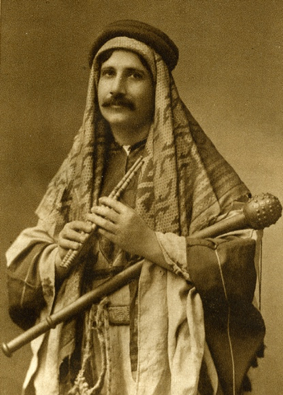

Two other Moghabghab brothers, Naoum and Faddoul, came to the United States in 1892. Naoum graduated in the first class of the Syrian Protestant College in 1870, Faddoul in 1886. After the Columbian fair, they began traveling around the country, Faddoul in the northeast and Naoum in the south, both calling themselves “Reverend.” Naoum preached and lectured on customs of the Holy Land in native costume. Faddoul was known for his interpretation of the Twenty-third Psalm, which he based on his supposed experience of being a shepherd in the Holy Land. He dressed up like a shepherd to give his talks. By his own reckoning, he had given more than five hundred lectures on the subject by 1907 (Figures 14 and 15). His message was immortalized in the book, The Song of Our Syrian Guest by William Allen Knight31 and in his own exegesis on the Twenty-third Psalm published in 1907.32

A well-known itinerant preacher and lecturer was Fares Anton Behannesey, who wrote and put on Oriental plays that were performed by local residents. The players wore costumes he brought with him, and he attracted a wide audience (Figure 15). One day, Behannesey disappeared; people feared him kidnapped. Because he was so well known, the story appeared in dozens of newspapers throughout the country. A year later, when he returned to the United States, he claimed he had indeed been abducted and taken by force to Beirut by his uncle, who was angry at Behannesey’s conversion to Protestantism. He announced to his fans that he had escaped and was on his way back to Chicago.

Abraham Rihbany also went on the lecture circuit throughout the Midwest in the 1890s. When he left New York to begin his travels in 1893, he says, he was given a supply of silk goods on credit to sell on his travels. He is one of the few Syrians to admit to having absolutely no head for business and hating the idea of buying and selling.33 It is a tribute to his skills as a lecturer and sermonizer and to the incredible generosity of the people he encountered in the Midwest, that he was able to become, with no college degree, no theological training, and imperfect English, a full-time minister in America.

Another nationwide lecturer was Asad Rustum, the son of Mikhail Rustum, who authored the 1895 book Stranger in the West, one of the earliest Arabic books published in the United States. Asad was called the “Syrian boy preacher” because he began traveling the church circuit at the age of seventeen along with his sister Effie, who was thirteen; he preached and she sang. Like the others, they lectured on the customs of the Orient, dressed up in costume, and performed “wedding and funeral ceremonies of the natives.”

Other illustrious nineteenth century Syrians, such as the writer Ameen Rihani, the physician Ameen Haddad, and the lawyer Nassib Shibley lectured around New York City on the subject of “Arabia.” They did not perhaps dress up or charge admission, but their task was both to educate and entertain the public.

WOMEN ON THE LECTURE CIRCUIT

Syrian women also went out on the lecture circuit and traveled widely. In 1890, Ramza Macksoud, her teenage niece Shafika Lutfy, and nephews Deeb and Ameen Lutfy traveled around the country giving demonstrations of Oriental customs. Ramza was the widowed sister of the successful New York merchant, Abdow Lutfy; Deeb, Ameen, and Shafika were his children. Deeb and Ameen worked with their father in his importing business and managed his stores in Saratoga Springs and Cleveland, yet they still had time to travel with their aunt. In each venue, Mrs. Macksoud took top billing. An “Oriental Reception” was usually given at the home of a prominent socialite and then repeated at a local church. The Lutfys were described as “native Syrians and representatives of one of the oldest and most aristocratic families of Damascus.”34 They reenacted a Syrian wedding, complete with five bridesmaids (these were local American women dressed in costumes brought by the Syrians), chanted wedding songs and served a “wedding feast” of Turkish sweets. They even gave a demonstration of Muslims praying.

The Macksoud-Lutfy performances encompassed all the essential elements of these lectures: attractive young people, dress-up, exotic rituals, sale of goods, and an emphasis on the Christian purpose of the performance. They always brought items to sell at the end of the lecture. One reporter commented, “The ladies who are right good looking for Syrians didn’t charge anything for the broken and otherwise mutilated English they distributed, but when their vocabulary gave out they offered for sale some articles they had with them.”35 In the announcement before one of the shows it was stressed, “They are not objects of charity, and no collection will be taken, but if any wish to buy any of their goods they will have the opportunity of doing so.”36 Mrs. Macksoud sometimes claimed that the items were made in Damascus by Christian students who were being supported by these sales. In fact they were probably goods that Abdow imported from his factories around the world, and the money from the sales went into the Lutfys’ pockets. Sometimes the Lutfys claimed to be earning money for college: Shafika “hoped to enter Wellesley,” Deeb planned to attend Union Theological Seminary, and two other Lutfys were supposedly “studying in Columbia College, New York City.”37 None actually did go to school.

In her first incarnation, a Syrian girl named Alice Azeez lectured on the “manners and customs of Arabs and Mohammedans of the Syrian desert” in New York churches in 1891 and 1892.38 She was only sixteen. Her English was apparently fluent, learned in British schools in Syria. She appeared in native costume and enhanced her talks by “playing Syrian airs on the piano.”39 She retired from public view in 1893, but in 1894 she appeared again, calling herself a Syrian princess by the name of Fannitza Abdul Sultana Nalide. She hinted that modesty had at first prevented her from revealing her royal status. She also claimed to be the “cousin of the wealthiest Arab in Beirut.” She told reporters that she had mastered seven languages, and that “specimens of her needlework adorned the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the Peabody Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts.” Her embroideries do appear in the collection of the Smithsonian, but it seems that these were purchased from her, rather than made by her. Like many of the other Syrian lecturers, she wanted to give her life to “the amelioration of the women of her race.”40 She was an enterprising young woman, taking out patents at the beginning of the twentieth century for fabric design and a showerhead that sprayed water in the shape of a flower. She became a landscape painter and lived with her sister, Marie el-Khoury, who was a prominent Fifth Avenue jewelry designer.

Other women lecturers in the 1890s took a different path, foreswearing costumes and reenactments and concentrating on delivering high-minded lectures on conditions in Syria or other topics, but each had a story to wring the hearts of her listeners. Layyah Barakat told a harrowing story about her persecution by the Turks. She was a Presbyterian convert from Abeih who married the lay Presbyterian minister Mohanna Elias Barakat; they reportedly narrowly escaped with their lives in the Alexandrian massacres of 1882 and came to America in August of that year. They both lectured around the United States beginning in 1883, sometimes together but usually separately. They would sometimes dress in native garb or demonstrate the Muslim call to prayer. She was paid a stipend by the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions—perhaps he was as well—which is why no mention is made of admission fees or sale of goods, but she would ask for contributions for Christian work in Syria.

The Protestant missionary Henry Jessup was a great fan of Mme. Barakat’s, feeling that she was an ideal spokesperson for the Presbyterians’ efforts in Syria.41 Others, however, were not as taken with her. A bitter letter from another Presbyterian missionary reads,

Layeh Barakat, one of the most earnest advocates of ‘doing something’ for Syrian woman and who showed considerable ability to interest people to give for missionary labor by a native of Syria, has not stepped foot on Syrian soil since she left it eleven years ago. All the money she has collected for missionary work is still in her possession, for nothing is being done, or has been done, unless an occasional dollar to her poor old mother is called missionary work.42

Harris does not go so far as to call her a liar or a charlatan, but we might infer that from his tone; by her lights, she was simply making a living by delivering a Christian message.

Hannah Korany had been a journalist in Syria before coming to the United States for the Chicago fair as the “representative of Syrian womanhood.” She traveled around the country giving lectures; she was well known and much admired. When she died in 1898 at the age of twenty-seven, she was widely mourned in American newspapers.

It is worth noting that many of these speakers, both men and women, were described as new converts from Islam to Christianity, but of course they were all Christians when they arrived here, and all had Christian parents and grandparents. Some of course may indeed have recently converted from Orthodox to Protestant, but it is well known that the number of converts from Islam to Christianity in Syria in the nineteenth century could be counted on the fingers of one hand.43Admitting this would have spoiled both the aura of sanctity around the new convert as well as diminish the thrill of the conquest over the Muslim heresy that Americans were so eager to support.

Like the more lurid entertainments represented by Little Egypt and the Moroccan minstrel shows, these nineteenth-century performance-lectures benefitted from and fueled the Orientalist craze sweeping the country. The dressing-up, reenactments, claims to Christian mission work, and hucksterism: one might say that they were simply another form of peddling, gussied up with educational, Christian, or intellectual pretensions. Yet unlike the belly dancers, these performers were respected by their audiences and by their fellow Syrians. The sale of goods, as we know, was the most common and valued way to earn a living in the Syrian immigrant community, and these lecturers were certainly entrepreneurs. All of these lecturers, both men and women, easily moved back into a settled life among their fellow Syrians. Mrs. Moghabghab and Mrs. Macksoud became pillars of the community. Did the lecturers and their families sincerely feel they were contributing to Americans’ understanding of the Middle East? Or were they simply peddlers and cynical actors exploiting the credulity of their American audiences in order to fill the family coffers? We have to assume both motives were at play: they were doing well by doing good. The North Africans and belly dancers, in contrast, were entertainers pure and simple. They made their living like any vaudevillian or circus performer, by anticipating and fulfilling the public’s desires.

As the Syrians became more prosperous and assimilated, as American entertainers coopted Orientalist themes, and as the Orientalist craze in America began to die down, Syrians stopped performing as Arabs (Arabs continued to perform in vaudeville well into the twentieth century, see Figure 3). What remained were the private family dress-up sessions, sometimes immortalized in photographs, when Syrians would put on “native costume.” Whether they had ever worn such clothes in Syria was unimportant. It brought back to them a life of which almost the only thing that remained was nostalgia (Figures 17 and 18).

FIGURES

NOTES

“The Asia Minor of New York,” Kansas City Star, 21 November 1898.↩︎

Advertisement, New York Tribune, 28 August 1863.↩︎

Advertisement, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 13 May 1884.↩︎

New York Herald, 29 March 1885.↩︎

“Barnum Overjoyed,” New York Times, 2 April 1886.↩︎

Advertisement, New York Herald, 5 October 1890.↩︎

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jz_9u9UZGUY, accessed 20 September 2014.↩︎

“Sie Hassan Ben Ali,” Kawkab America (English), 4 November 1892.↩︎

The (NY) World, 16 October 1898.↩︎

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yftSkqGDlfM, accessed 20 September 2014.↩︎

“The Egyptians at the Immigration Bureau,” Kawkab America (English), 7 April 1893.↩︎

“Those Wicked Dances,” Tacoma (WA) Daily News, 15 August 1893.↩︎

“Now Which ’Tis, Anyway?” Anaconda (MT) Standard, 10 January 1898.↩︎

Even Ashea Wahby may have been an American named Catherine Divine.↩︎

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zxZoXJBILbc, accessed 23 September 2014. Why men would pay to see this film on a Kinetoscope when the real thing was so close at hand is puzzling. The new medium itself must have been the draw.↩︎

Advertisement, Evansville (IN) Courier and Press, 22 April 1886.↩︎

San Francisco Chronicle, 14 March 1892.↩︎

Advertisement, New York Herald, 16 April 1893.↩︎

“Arab Whirlers in Court,” New York Tribune, 25 March 1899.↩︎

“Murray Was Acquitted,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 13 August 1897.↩︎

“Purging Coney Island,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 18 August 1897.↩︎

“Pictures of Fair,” Watertown Daily Times (Watertown, MA), 27 May 1904.↩︎

The Billboard, 1902–1904: 7.↩︎

“Oriental, But Shrewd,” The (NY) Evening Telegram, 31 October 1893.↩︎

Advertisement, Boston Journal, 2 November 1880.↩︎

“Odd Sights in Brooklyn, A Howling Dervish in Mr. Beecher’s Pulpit,” New York Times, 11 December 1880.↩︎

“Wedding by Moslem Rites,” New York Times, 24 March 1897.↩︎

“An Oriental Entertainment for the Mystic Shriners,” Kawkab America (English), 20 January 1893.↩︎

Kaleel was in fact considered to be a “native pastor” by the Presbyterian Mission in Syria. The Foreign Missionary, 29 (1871): 303.↩︎

“Day’s Diary,” Aspen (CO) Daily Chronicle, 13 October 1891.↩︎

William Allen Knight, The Song of Our Syrian Guest (Boston: Pilgrim Press, 1904). The book went through several printings. Moghabghab sued Knight for using his name and his stories without permission but lost the case, which was probably why he decided to write his own book.↩︎

Faddoul Moghabghab, The Shepherd Song on the Hills of Lebanon (New York: E.P. Dutton & Company, 1907).↩︎

Abraham Mitrie Rihbany, A Far Journey: An Autobiography (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914), 248.↩︎

“Oriental Reception,” Rocky Mountain News (Denver, CO), 21 January 1891.↩︎

“The Syrian Ladies’ Show,” Daily Register (Rockford, IL), 5 June 1890.↩︎

“Real Syrian Women Will Talk,” Daily Register (Rockford, IL), 4 June 1890.↩︎

“At the Churches,” Rocky Mountain News (Denver, CO), 11 January 1891.↩︎

“Our New York Letter,” St. Louis Republic, 29 November 1891.↩︎

“In Her Native Garb,” The (NY) Press, 6 March 1892.↩︎

“Talented and a Princess,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, 23 September 1894.↩︎

Letter from H.H. Jessup to Ellinwood, 8 July 1884. “I little thought when she sat on a mat in my house in Mt. Lebanon in 1872, that in twelve years that Syrian girl would be melting great congregations to tears by her pathetic story far beyond the seas!”↩︎

Letter from Harris to Ellinwood, 25 September 1893.↩︎

Many of the letters of the Presbyterian missionaries in Syria list the number of visits they had made to Muslims in the previous period; apparently the mere fact of the visit was seen as progress toward conversion and counted as a victory. Reports of actual Muslim conversions do not appear.

Picture Credits: 1, 6, 9, and 10, Anonymous, Portrait Types of the Midway Plaisance (St. Louis: N.D. Thompson, 1894?). 2, Gail O’Keefe Edson. 3, Collection of the author. 4, Julia Fuleihan. 5, Nancy Fuleihan. 7 and 8, J.W. Buel, The Magic City, (St. Louis: Historical Publishing Co., 1894). 11-13, National Anthropological Archives of the Smithsonian Institution. 14, Collection of the author. 15 and 16, Faddoul Moghabghab, The Shepherd Song on the Hills of Lebanon (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1907). 17 and 18, Helen Samhan.↩︎