Dahlia El Zein

FROM SHIA`A TO WHITE: RACE AND COLONIALISM IN KAMEL MUROUWWA’S NAHNU FI IFRIQIYA

Abstract

In 1938, Lebanese Syrian publisher Kamel Murouwwa extensively

toured West Africa and produced a 329-page travelogue entitled Nahnu

Fi Ifriqiya: al-Hijra al-Lubnaniyya al-Suriyya ila Ifriqiya

al-Gharbiyya, Madiha, Hadirha, Mustaqbaliha (We are in Africa:

Lebanese Syrian migration to West Africa, its past, present, and

future). In this article, I use Murouwwa’s travelogue as a lens to

understand the process of racial identity formation in West Africa from

a Lebanese visitor’s perspective in the 1930s under French colonialism.

Murouwwa’s source has been underutilized as a rich text of thick racial

and at times racist description. This article argues that through the

process of racial identity formation in West Africa, Lebanese Shi’is

were able to transcend emerging sectarian identities prevalent in newly

carved Lebanon which marked Shi’is as “metwali” (backward).

Lebanese migrants’ “whiteness” became the most pronounced marker of

their presence among local Africans, overshadowing religious identity

and erasing any “backwardness” associated with Shi’is in Lebanon,

elevating the community to the class of colonizer versus colonized.

Sectarianism carries significant weight within the confines of the

nation-state, but a broadened transnational approach to sectarianism

provides a widened view to see how racial identity supplanted sectarian

identity outside the nation-state.

ملخّص

في عام 1938، قام الناشر اللبناني السوري كامل مروة بجولة مكثفة في غرب أفريقيا وأنتج كتاب رحلة مكون من ٣٢٩ صفحة بعنوان نحن في أفريقيا: الهجرة اللبنانية السورية إلى أفريقيا الغربية، ماضيها، حاضرها، مستقبلها. في هذا المقال، أستخدم قصة رحلة مروة كعدسة لفهم عملية تشكيل الهوية العرقية في غرب إفريقيا من وجهة نظر زائر لبناني في الثلاثينيات في ظل الاستعمار الفرنسي. لم يتم استغلال مصدر مروة بشكل كافٍ كنص غني يتعمق بالوصف العرقي، وفي بعض الأحيان بالوصف العنصري. يقترح هذا المقال أنه من خلال عملية تشكيل الهوية العرقية في غرب أفريقيا، تمكن الشيعة اللبنانيون من تجاوز الهويات الطائفية الناشئة السائدة في لبنان المكون حديثًا والذي ميز الشيعة على أنهم "متاولي" (متخلف). أصبح "بياض" المهاجرين اللبنانيين هو العلامة الأكثر وضوحا لوجودهم بين الأفارقة المحليين، مما حجب الهوية الدينية ومحا أي "تخلف" مرتبط بالشيعة في لبنان، مما رفع الجالية إلى طبقة المُستعمِر مقابل المُستعمَر. تحمل الطائفية وزنًا كبيرًا داخل حدود الدولة القومية، لكن النهج العابر للحدود في دراسة الطائفية يوفر رؤية موسعة لمعرفة كيف حلت الهوية العرقية محل الهوية الطائفية خارجلا يرى غير الظلام.

INTRODUCTION

On 19 April 1938, the Lebanese Syrian publisher Kamel Murouwwa (1915–1966) boarded a ship at the Beirut port headed for Dakar, Senegal.1 Murouwwa was dispatched to collect donations for the Shi’i ‘Amiliyya Association from Lebanese Syrian Shi’i families in West Africa. Two weeks later, he landed in the capital of French West Africa, the first of several trips. Over the next four months, Murouwwa extensively toured colonial West Africa, documenting his experiences in a 329-page travelogue, Nahnu Fi Ifriqiya: al-Hijra al-Lubnaniyya al-Suriyya ila Ifriqiya al-Gharbiyya, Madiha, Hadirha, Mustaqbaliha (We are in Africa: Lebanese Syrian migration to West Africa, its past, present, and future).2

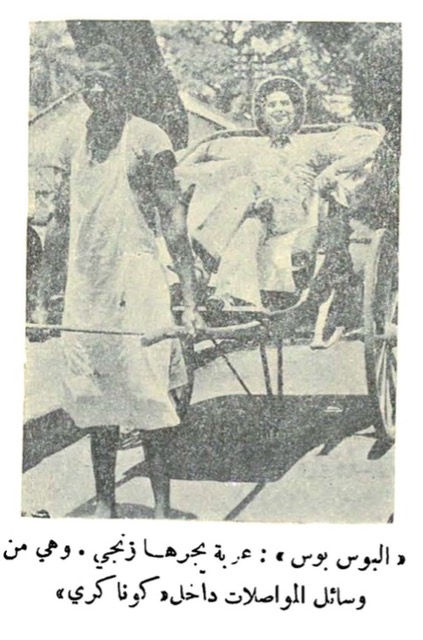

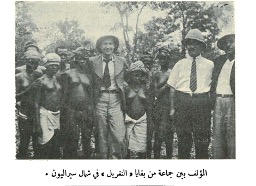

Above are two photographs of the author from Nahnu Fi Ifriqiya (see Figure 1 and 2). The first image on the left features Murouwwa sporting a wide-brimmed hat and smirking at the camera as he sits back in a carriage pulled by a smiling West African young man. The caption reads: “ ‘Al-bus-bus’: a cart pulled by a negro (zinji). And it is one of the modes of transport in Conakry” (172). In the second image, on the right, a smiling Murouwwa in his pith helmet and fitted suit stands in the middle with his arms around several young bare-chested Sierra Leonean young women and girls flanked by two of Murouwwa’s Lebanese Syrian traveling companions. The caption reads: “The author between a group from the ‘Naghreel’ in the North of Sierra Leone” (24). Murouwwa’s exotification of “natives” in these portraits strongly evokes the colonial photographs from late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century European explorers and anthropologists.3

Why was Murouwwa emulating the image of a European anthropologist in West Africa? These images of colonial roleplay in Murouwwa’s travelogue raise questions about the racial identity of Lebanese Shi’i migrants and visitors in West Africa during the early twentieth century. Murouwwa’s source has been underutilized as a rich text of thick racial and at times racist description deeply rooted in ideas of aspirational whiteness, distaste for blackness, and the language of manifest destiny by a Lebanese man who actively probed the contours of empire and the technologies of steam and print in the early twentieth century. An analysis of his travel writing provides an intimate perspective into how the dialectic of colonial racial ideas influenced the self-perception of race as a system of social differentiation among Lebanese visitors to West Africa at this time, within the purview of French colonialism.4

In this article, I use Nahnu Fi Ifriqiya as a lens to understand the process of racial identity formation in West Africa for Lebanese Syrian Shi’is. For Murouwwa, Lebanese Shi’is could lean into a perceived whiteness and “modernity” by classifying themselves as “white migrants” (muhajeerna al-beed) and subsequently distancing themselves from blackness and “backwardness” by referring to all Africans with the pejorative Arabic term for slave, “abeed.” Through this racialization process in West Africa, Lebanese Shi’is were then able to transcend emerging sectarian identities prevalent in newly carved Lebanon (Grand Liban) which marked Shi’is as “metwali” (backward) and as a colonized subservient class, by projecting those anxieties onto Africans.5

While the Lebanese Shi’i community in West Africa achieved higher status within the colonial order compared to autochthonous West Africans, such as obtaining loans from European banks, they also found equal footing with fellow Lebanese Syrians—Christian or Muslim—which they struggled to do in Lebanon under the French mandate (1920–1946).6 Lebanese migrants’ “whiteness” became the most pronounced marker of their presence among local Africans, overshadowing religious identity and thus erasing any “backwardness” associated with Shi’is in Lebanon, elevating the community to the class of colonizer versus the colonized.

Accounting for how race and sect moved through time and space from Lebanon to West Africa within a colonial framing enriches our understanding of both phenomena.7 Racism coexisted with sectarianism as a system of social differentiation. More than contributing to a Lebanese “Shi’i” sectarian identity, the presence of the Lebanese diaspora in West Africa contributed to a Lebanese racial identity that was in effect anti-sectarian. By examining Murouwwa’s journey from Jabal ‘Amil to Dakar, I uncover how he saw the process of racial identity formation and sectarian shedding for Lebanese Syrians in the context of West Africa. I want to emphasize here that Murouwwa’s understanding of the racial identity formation of Lebanese Syrians in West Africa reflected how Lebanese visitors to West Africa in the 1930s perceived the intersection of race and colonialism in a trans-imperial context. However, it does not necessarily reflect how Lebanese Syrians saw and understood themselves racially in West Africa under French colonialism.

EMPIRE, TRAVEL, AND TRAVEL WRITING

From the hilly southern region of Jabal ‘Amil, Kamel Murouwwa was a prominent figure in the Lebanese press. Murouwwa was a successful journalist and publisher, often referred to as the “father of modern Arab journalism” (Abu al-Sahafa al-‘Arabiya al-Mu’asira). He was renowned for the publication of three leading newspapers in contemporary Lebanon: the Arabic language daily Al-Hayat (1946), its English-language counterpart The Daily Star (1956), and the French-language Beyrouth Matin (1959).8Born in 1915 in Zrariyeh, in today’s South Lebanon while it was part of the Ottoman Empire, Murouwwa came of age during the French mandate era (1920–1946), a time of extraordinary change in the region.9 Jabal ‘Amil is difficult to define geographically as, historically, it did not officially exist as a legal, bordered entity under the Sunni-dominated Ottoman Empire (1516–1918), the French mandate (1920–1946), or the independent Lebanese state of 1943.10 The region was primarily inhabited by Twelver Shi’is who called themselves “ ‘Amilis,” as a reference to belonging to Jabal ‘Amil. Druze, Greek Orthodox, and Maronite communities also existed (and continue to), albeit in much smaller numbers. Although marginalized in Lebanese historiography, the region of Jabal ‘Amil existed for hundreds of years. It was a center of Shi’ite Islamic learning, abuzz with intellectual life particularly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with many ‘Amili ulama serving in Persian Safavid courts.11 Under the Ottomans, after the Tanzimat administrative restructuring of 1864, Jabal ‘Amil fell under Vilayet Beirut which shifted the focus of trade to Beirut, away from the southern ports of Saida or Tyre. By the late nineteenth century, the Shi’i ‘Amilis were “a peripheral rural Ottoman community.”12 With the creation of Lebanon under the French mandate, parts of Jabal ‘Amil were established as the province of South Lebanon, where some villages that had historically been considered part of the region were given over to Mandatory Palestine and Syria.13

This background on Jabal ‘Amil offers context as to why Murouwwa in Nahnu fi Ifriqiya refers to himself, Lebanese migrants, and Lebanese Syrian Shi’is as “al-Lubnaniyoun al-Suriyoun” (Lebanese Syrians) but not as Shi’is.14 Even though Murouwwa was writing during the pinnacle of French mandate rule, which prompted Shi’is to create a distinctly sectarianized legal and political identity, the self-referential term “Shi’is” was not yet in widespread use.15 He only refers to the association as the “‘Amiliyya” and frames his trip within a nationalistic framework: “To serve my country” (li khidmat baladi) (10). I am using the term “Shi’i” in this research to reference the community of Lebanese Syrian migrants in West Africa who might have been classified in the 1932 census as “Shi’i” in mandate Lebanon and also to reference Lebanese Syrians (such as Murouwwa) who belonged to a broader ‘Amiliyya sociopolitical landscape.16

Although marginalized in the historiography, ‘Amilis in the early twentieth century were active participants of the Nahda (Arab Awakening), a period during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries of a burgeoning intellectual scene in the broader Islamic world.17 A member of this Shi’i ‘Amiliyi elite, Murouwwa belonged to a later generation of these Nahdawi Arab intellectuals who encountered European ideas of biological racism, “white” superiority, and colonialism prevalent in the Nahda milieu.18 Despite this class of educated Islamic scholars and notables in Jabal ‘Amil, its largely rural population faced immense poverty in the interwar period. The famine and subsequent widespread disease that affected the Greater Syria region in World War I is well-documented as being especially dire in Lebanon.19 Scholars estimate that some 500,000 had died by the end of the war during what in collective memory is referred to as the safarbarlik.20 The residents of Jabal ‘Amil were also largely illiterate; education under the Ottomans and subsequently the French was dismal compared to other regions of Greater Syria.21 Rashid Beydoun established The Charitable Islamic ‘Amili Society (al-Jam‘iyya al-Khayriyya al-Islamiyya al-‘Amiliyya) in 1923 with the aim of providing educational opportunities for disadvantaged Shi’is. In 1929, the group established an elementary school in the Beirut neighborhood of Ra’s al-Naba’a where many Shi’is lived.22 By 1932, the rapidly expanding population of South Lebanon had reached over 75,000 inhabitants (by 1943 it tripled to 200,000).23 As more ‘Amili youth moved to the growing urban center of Beirut in search of educational and work opportunities, the association struggled to absorb its large numbers. Murouwwa, an active member of the association, suggested to Beydoun that they embark on a fundraising trip to West Africa to raise money from the financially successful Lebanese Syrian ‘Amiliyya community there.24 Murouwaa’s idea was likely inspired by the funding Maronite institutions in Lebanon received from their diasporic Maronite counterparts in the Americas.25

Even before setting foot in West Africa, Murouwwa already had a complex constellation of racial ideas around whiteness and blackness informed by his upbringing. Murouwwa’s father, Mohamed Jameel Murouwwa, had been living in the diaspora in Mexico and returned to Lebanon during the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) in 1912, settling in Saida (Sidon) and marrying a woman from Zrariyeh, Badi’aa Mohyideen.26 It is not unlikely that Murouwwa’s father communicated to his son some of his own racial ideas around whiteness and blackness, which were shaped by his life during the late nineteenth century in the Mexican city of Hermosillo.27 Arabs registered themselves as “white” in the Mexican state registers during this period.28 After Murouwwa’s father died in 1925, his single widowed mother raised Murouwwa and sent him to the Gerard Institute for Boys in Saida, known as the “American” school, which was part of the National Evangelical School for Boys and Girls founded by American Protestant Missionaries in 1862.29 Scholars have documented how American missionaries in the region brought their understandings of racial order as informed by Atlantic world slavery, Native American genocide, and eugenics, among other phenomena.30 In school, Murouwwa learned English, Arabic, and French, providing him with advanced literacy and access to the writings of many European and American authors, whether his contemporaries or of an earlier colonial era.31 He was the editor of the school journal, Al-Madrasa (The School), and was awarded a scholarship to attend the American University of Beirut in 1932, another institution with its roots in American missionary work from the late nineteenth century.32 As a young boy, Murouwwa’s developing racial ideas would have been informed by his father’s diasporic experience as an Ottoman Syrian in Mexico as well as his experience as a student at an American Evangelical missionary school in Saida.

As a beneficiary of missionary schools with fluency in European languages, Murouwwa was able to move with ease within the French empire. This age of empires also brought the age of steam and print, allowing for the movement of people and ideas at a speed never seen before.33 Migration became more affordable for people living under unjust rule and dire economic circumstances such as Lebanese Syrians, first under Ottoman and then French rule. In the 1920s and 1930s, under French mandate rule, thousands of Lebanese Syrians migrated to French West Africa, Afrique Occidentale Française (AOF) (1895–1958)34 French colonial rule also facilitated travel within and between imperial polities. Murouwwa benefitted from this intracolonial travel, traveling around West Africa, visiting cities and villages, posing with locals, jotting down his observations of local customs and cultures, meeting with Lebanese Syrian migrants, and utilizing the numerous modes of transport offered by the empire.

During his four-month trip, Murouwwa visited: Senegal, French Guinea, Dahomey (Benin), French Sudan (Mali), Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, and the Gold Coast (Ghana). He returned to Beirut on 10 September 1938 (9). Murouwwa arrived in Dakar by ship and moved from one colonial hub to the next by car, train, canoe, carriage, and human porterage, all transports facilitated by French and British colonial field offices. During his travels Murouwwa kept a diary, which he would later publish as a travelogue dedicated to the Lebanese Syrian migrants of West Africa (10). Murouwwa makes it clear that he is writing this book both for the immigrants and Lebanese nationals (abnaa al-watan), covering “what our immigrant needs to know about the African countries which they live in and what our national needs to know about the countries in which their immigrant brothers live” (15). He also gives special thanks to the official colonial authorities in African countries for facilitating his trip and adding important details to the book (10).

Nahnu fi Ifriqya is a colossal travelogue, comprising three parts with forty-four sections. In 1938, Murouwwa wrote what can also be considered as a historical and anthropological study, albeit in a self-important and all-knowing tone. In part one, “What is West Africa?,” Murouwwa offers a detailed history, geography, cultural, and demographic breakdown of all the countries in West Africa as well as an overview of colonial West Africa, the history of colonialization, and a snapshot of each colony in French and British West Africa. Part two offers an extensive overview of the history and current trends of Lebanese Syrian migration to West Africa and the situation of the community in French and British West Africa, including a breakdown of the numbers of migrants in each colony (185). The last part is what he calls the “challenges and problems” facing Lebanese Syrians migrants in the past, present, and future (235).

While we do not know the breadth of Nahnu fi Ifriqiya’s readership, it was first published as a series of vignettes in the weekly newspaper Al-Makshuf, founded in 1935 by Sheikh Fouad Hobeiche, and thereafter published as the book by its subsidiary publishing house, Dar Al-Makshuf. The fact that it was initially circulated as vignettes suggests a broader audience than if it had only been disseminated as a book. Al-Makshuf itself was the subject of much controversy and known for its proactive content including erotic literature, nude images, and criticism of traditional and religious values. It frequently faced censorship and was eventually forced to shut down in 1939. Al-Makshuf was popular among intellectuals and artists and is estimated to have had a circulation of about 10,000. It was distributed in Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Iraq, and other countries.35 Given the popularity of Al-Makshuf, the contents of Nahnu fi Ifriqiya would likely have reached a substantial audience.

Moreover, in the late 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, Murouwwa was a giant in the Lebanese and broader Arab nationalist political scene. His newspaper Al-Hayat became (and remains) one of the most influential newspapers in the Arab world, rivaling Egypt’s largest newspaper, Al-Ahram.36 He visited the controversial figure of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, in Germany during World War II. In 1954, he co-authored a publication with renowned Arab nationalists Akram Zataari and Sati’ Al-Husari entitled “A Letter on Unity.” Murouwwa openly opposed the military dictatorships that came to rule the Arab world in the 1950s and 1960s, advocating for democracy and secularism. He also developed strong links with Lebanese Syrian Shi’is in Dakar, having corresponded with several influential men in the community and taking several follow-up trips to West Africa.37

The popularity of the travelogue genre during this time also indicates its reach. Travel writing was most closely associated with early European explorers documenting their fascinations with “native” societies and cultures. Given its rise during the colonial period and with the spread of print culture, increasing literacy, and relative ease of travel facilitated by empires, travel writing became common among bourgeois travelers from across the world, including within what today scholars call the global South. Lebanese Syrian and Arab writers were no exception. Kamel Murouwwa is one example of many Lebanese travelers to West Africa who documented their experiences and observations in travel journals or memoirs, including ‘Amiliyya president Rashid Beydoun and the head of the Ja’fariyya association, Ja’far Sharaf el-Din.38 The commonality of language expressing aspirational whiteness and distaste for blackness in travelogues written during this period strongly suggests that Murouwwa was not an outlier but rather actively engaged with the larger dialectic of colonial racial ideas circulating at the time.

“OUR WHITE MIGRANTS”

From the start of his travelogue, Murouwwa firmly establishes Lebanese Syrians as “abyad” (white) and on the same “civilizational” level as European colonizers. Throughout his writing he exclusively refers to the migrants as “muhajeerna al-beed” (our white migrants) or al-Lubnaniyoun al-Suriyoun (Lebanese Syrians), noting “of the 14,000 whites in Senegal, 4,500 were Lebanese Syrians” (12). He does not refer to them (or himself) as “Arabs” at any point. His utilization of essentialized racial categories such as “white,” “black,” “yellow,” “brown,” and “red,” framed in the developmental language of “progress” and “regression,” reveals his beliefs in a white/black, civilized/uncivilized, modern/backward binary. Although Murouwwa's racial classifications included what Brahim El Guabli calls a “geometry of racializations” by distinguishing between the white origins of Africans as Arabs, Tuareg, and Tamazight as well as the black origins of Africans as Wolof and Sudanese, he viewed French-white as different.39 It was clear to him on which side of the binary Lebanese Syrians sat in West Africa, redeeming Lebanese Shi’is of any associations with “backwardness” carried in Lebanon.

Murouwwa describes West Africa as the “graveyard of the white race” where the “intelligence of the white man” will spread its riches throughout the world much like the blessings of American cities (11). Murouwwa’s reference to the “white man” includes Lebanese Syrians—“our immigrant is the only white to brave the African interior” (12–13). He makes them out to be even more impressive than Europeans whom he criticizes for relying on too many “comforts” (248). By situating the narrative of Lebanese Syrian migration within a lexicon of manifest destiny, Murouwwa firmly positions Lebanese Syrian migrants as colonizers versus colonized and projects an image analogous to pioneers.

The self-racialization of many Middle Eastern elites as white in the early twentieth century is a well-documented phenomenon among historians and scholars.40 During this time, Arab and Middle Eastern immigrants in the United States, Australia, and South Africa were fighting for whiteness in courts.41 For example, some Lebanese Syrian Maronite Christians argued that as Christians they were more European than Arab. The claim to whiteness, however, was not unique to Maronites; Muslim Middle Easterners, including Lebanese, likewise identified as white.42 However, “whiteness” as a category did not have the same resonance within each Arab and Middle Eastern context.43 Previous studies on the Lebanese diaspora have successfully argued how Lebanese Syrians in the Americas assimilated into whiteness facilitated by Christianity.44 Lebanese Syrian Shi’is then and now made up the majority of migrants in West Africa, unlike in the Americas, where the majority was largely Christian or Jewish. Estimates put the number of ‘Amilis in West Africa at 75–95 percent of the Lebanese Syrian migrant community, as early as the 1910s, meaning these were primarily Muslims among African Muslims.45 Unfortunately, we lack the same depth of understanding into how Lebanese Muslims understood racial difference among fellow Muslims in places such as Senegal, for example.46

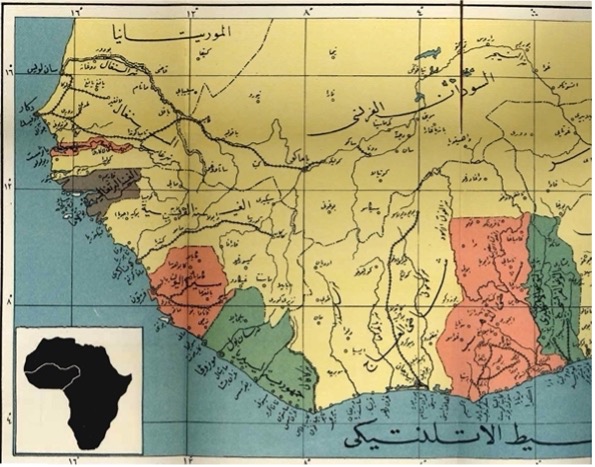

Murouwwa reinforced the myth that Lebanese Syrians migrants’ presence in Senegal and West Africa was justified by the accidental nature of their arrival.47 He suggested that these migrants were headed to the United States or Latin America but ended up in West Africa after failing health exams or running out of money (191–2).48 Senegal became a hub of Lebanese Syrian migration, which Murouwwa refers to as the “doorstep to Africa” (‘atabat ifriqiya), with many migrants staying in Dakar or Saint Louis, moving to the interior of the country, or going to other West African polities, as seen in his map below (Figure 3). In 1900, there were 400 Lebanese Syrian migrants in West Africa, with 267 in Senegal. By 1938, the number had grown to over 10,000, with 2,800 in Senegal and 1,600 in Dakar. Murouwwa even notes, “When you walk the streets of Dakar, you will be surprised by the number of our immigrants. . . . They are spread everywhere without exception” (198). Although the greatest concentrations of Lebanese migrants could be found in Dakar and Saint Louis, almost every village in Senegal had at least one Lebanese family.49

While Murouwwa’s writings aligned with other Arab elites during his time, his enthusiasm for colonialism was unusual within the context of the French colonization of Greater Syria, which was largely opposed by many Lebanese Shi'is and Arabs.50 1925–1926 marked the Great Syrian revolt, and even in French West Africa many Lebanese Syrians were being surveilled by French intelligence services for their anti-colonial writings.51

Murouwwa writes, “Some might blame me for exaggerating the white contribution in West Africa and consider it glorifying colonization, call it what you want, colonization or investment, oppression or adversary, but we have to recognize the direct and indirect results of it” (12). His Darwinian attitude understood whiteness as synonymous with colonization and civilization. He claimed that “colonization is the first step to civilization,” and in his reading, Lebanon was already civilized and therefore not colonized (at least not in the same way) (13). He supported this argument by boasting Lebanon’s high ranking in the French mandatory hierarchy as a “Mandate A” territory.52 Furthermore, he directly implicated Lebanese Syrians as part of the white colonial project of Africa, proclaiming, “I am proud that Lebanese Syrians are developing this civilization” (12). In West Africa, Lebanese Shi’is could shed their Shi’a layer and become the “civilizers,” as opposed to those who needed to be “civilized,” which was the case in Lebanon.

Colonial categories were not fixed but instead everchanging politically contested sites which varied from one colonial context to the next.53 Lebanese Shi’i migrants from Jabal ‘Amil, historically dispossessed and marginalized, found in Africa the promise of prosperity and upward mobility in the Lebanese Syrian social hierarchy.54 In contrast to their “metwali” status at home—a derogatory term implicating “backwardness,” “filth,” and lack of “class”—in Africa they could attain almost equal footing with the colonizer, on the one hand, and with other Lebanese Syrians, on the other hand. Murouwwa reinforced this modern/backward binary by commenting that “many migrants are from the villages, and they are backwards and uneducated” (288). For Murouwwa, the higher societal position that Lebanese Shi’is could attain in West Africa offered redemption for what he otherwise considered incurable qualities in the Lebanese societal context.

Murouwwa’s fears of how Shi’is were being perceived were not unfounded. Other Lebanese migrants in West Africa also carried unsavory narratives about the Shi’a. Andrew Arsan recounts one such instance of Georges Thabit who wrote that the Shi’a “were not only guilty of ‘making money by illegal means’, commonly using ‘reprehensible’ practices Christians and Sunnis only sometimes relied upon. They also ‘lived in the same condition as the blacks, even marrying Negro women’.”55 Shi’i men would more openly engage in conjugal relationships with local African women since divorce was permissible in Islam, and they could enter into “temporary marriages” with these women, known as “mut’aa.”56 Murouwwa echoed Thabit’s concerns, seeing proximity to Africans as a distancing from Europeanness (whiteness) and hence from colonial ideas of “respectable” behavior which took hold among global elites in the early twentieth century.57 And while he praised the ability of Shi’i migrants to live like local Africans as their most entrepreneurial quality—living deep in the interior of the colonies and eating a similar diet as local West Africans—he also uses this as a mark against them. He expressed great lament about the lack of Lebanese children’s familiarity with Arabic, “My heart hurts because fifty percent of the children don’t know Arabic, they know French or English and some of the ‘zunuj’ languages like Wolof, Mande, or Serer” (290).

In Lebanon, under French colonial rule, Maronite Christians generally received economic and political preference while Lebanese Shi’is were frequently excluded from educational opportunities, economic growth, and social services.58 In Africa, Lebanese Shi’is could overcome this marginalization to achieve equal footing with other Lebanese Syrian migrants. Their access to loans from European banks provided them with seed capital, enabling them to offer loans to local West Africans at high interest rates.59 This phenomenon of shifting colonial-induced hierarchies was not unique to Lebanon and Syria, but a trend observed across many colonial contexts.60

While Murouwwa may have perceived Lebanese Syrians as closer to Europeans than Africans, the French did not. Murouwwa lamented that there was still a divide between Europeans and Lebanese Syrians that prevented their “white brothers” (ikhwana il-beed) from the appreciation and respect that Lebanese Syrians deserved (278). Murouwwa’s reference to French and Europeans as “our white brothers” underscores his understanding of Lebanese whiteness as identical to French whiteness. He even distinguishes the 3,500 Portuguese in Senegal as “brown” (195). Even though official French colonial documents classified Lebanese Syrians as belonging to “les races blanches” (the white races), for the French, they remained a colonized class. Colonial documents described the community as “miserable Lebanese shopkeepers, who barely speak French, are illiterate and serve mostly an African clientele.” They also complained that they were anti-French but forced their way into competing alongside French trading companies.61 Lebanese Syrians were subjected to consistent migration restrictions by French colonial authorities because of the threat they posed to French economic hegemony in West Africa.62 However, as trade demand increased, Lebanese came to play an essential role as “middleman” (traitants)—buying directly from peasant farmers and transporting the produce to trading centers.63 European trading firms began hiring more Lebanese for this role because they were less expensive—single men willing to live on little compared to their West African counterparts.64 These migrants came to own a large proportion of trading shops and real estate in Senegal and Cote d’Ivoire, which led to increasing resentment from locals.65

Murouwwa’s aspirational whiteness dismantled the colonial logics of “French-whiteness” but only by expanding the definition of white to include Lebanese Syrians, not in questioning the binary itself. His disdain for blackness was equally totalizing. For Murouwwa and Lebanese Syrians Shi’is to become white and colonizer, all Africans had to become colonized, backward, subservient, and enslaved. Even though he differentiated in the “black origins” of Africans, as demonstrated by his mention of the Wolof of Senegal whom he considered “black” and the Sudanese people whom he classified as “burned brown or light brown,” throughout his entire book he refers to black Africans as “‘abeed,” inscribing a permanent subservience on all Africans, whilst simultaneously reflecting his anxieties of Shi’is as a subservient class in Lebanon (35).

“FOR EVERY BLACK PERSON”

We are used to saying the word ‘abd’ for every black person, and especially for the black people of Africa. And the word ‘abd’ in its roots means black slave and is not used on black people except for slaves. Except this term people got used to saying this word ‘abd’ for ‘zinji’ or ‘aswad.’ (29)

In the above quote, even though Murouwwa acknowledged that by no means were all Africans enslaved, he says that people in the Arabic-speaking world used the term “abd,” meaning slave, for “every black person.” Murouwwa’s repeated flattening of Africans with racist and racializing terms such as “zunuj” (negroes), “‘abeed” (slaves), or “sud” (blacks) essentialized a timeless, faceless, primordial image of all African men and women, erasing their differences—tribal, social, and religious. His racializations also mirrored the 1930s world in which Murouwwa lived. By the early twentieth century, deep linkages between slavery and anti-Blackness had developed in the Mediterranean world. This reflected the longstanding history of Middle Eastern and North African enslavement of Black Africans prior to European colonization and further hardened under colonialism.66 Slavery in the Middle East prior to the eighteenth century was not racialized in the same way as in the Atlantic world and included Circassians and Christians from European and Balkan Ottoman lands. But it became increasingly more racialized during the nineteenth century as the bulk of the slave trade shifted to the Nile Valley, necessitating imagined justifications of anti-blackness. Murouwwa’s persistent usage of “‘abeed” as a synonym for Africans throughout ignores the painful connotations and inherent violence that these words carry, its meaning much more pejorative than its translation of enslaved person.67

In his introduction, Murouwwa portrays black Africa as a land of darkness and slavery, extending “from the coast of the sea of darkness (shat’ il-bahr il-tholoma’) to southern Marakeesh and from the coast of slaves (sahel il-raqeeq) to the depths of the greater desert where you will find white intelligence and the liveliness of blacks meet” (11). “Liveliness of the blacks” reveals Murouwwa’s reading of fourteenth-century Muslim scholar Ibn Khaldun’s racial ideology found in al-Muqaddimah.68 This is not to suggest a teleological continuation of a fixed anti-blackness from Ibn Khaldun’s fourteenth-century world to the early twentieth century but rather that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries classical texts were given new life.69

The Shi’i monthly periodical Al-Irfan in the early decades of the twentieth century also echoed these highly racialized portrayals of Africans.70 The journal translated several articles by Europeans and Americans about their adventures into Africa and observations of African “cannibalism.”71 Several scholars have written about the resurrection of classical texts in this period as well as the popularity of European and American writers among Arab intellectuals. 72

In a 1912 volume of the journal, Abd al-Aziz al Jawahiri, in an article entitled “Natural Selection” (al-intikhab il-tabee’i), highlights the arguments of Charles Darwin and quotes from Ibn Khaldun saying “that the people of Africa are lazy and cowards because they live in hot weather.”73 The interest in Darwinian racial ideas and natural selection—that skin color and racial variation were caused by climate and social habits—was highly influential in many Arabic periodicals and elite circles at the time.74 In 1912, Jurji Zaydan, Lebanese novelist, journalist and founder of Al-Hilal, published a popular study of the world’ races, Tabaqat al-Umam, which likely influenced the writers of Al-‘Irfan.75 Another article in the journal entitled “Among Cannibals” (bayna akalat luhum al-bashar) is a translation of an entry by Martin Johnson in an American newspaper about the practice of cannibalism among the “zunuj.”76 In the same volume, Adeeb al-Talqi al-Baghdadi, under a series of articles entitled Strange Habits (ghara’ib il-‘adaat), accuses Africans of the “sale of children” and that “most of them get married for this purpose,” adding that there is “no difference in the way they raise their children or livestock.”77

Like Ibn Khaldun and the many French, German, and English anthropologists whom he cites, Murouwwa fashioned himself as a type of historian-anthropologist (319).78 He provides a detailed overview of the history of Africa before colonization and a snapshot of each colony in West Africa. However, more than a genuine recognition of varied African cultures, Murouwwa’s descriptions of the differences between West Africans harkens back to early European anthropological writings’ fascination with “exotic” cultures. He writes, “It is difficult for the white man to differentiate between the blacks, but we should try to know their differences” (29). In a de-racializing moment, Murouwwa warns his readers that “anyone who believes Africa did not have a history before colonization is mistaken because they had major kingdoms and international life” (22).79 He further writes, “The blacks like all people have different traditions but they are a world on their own and very far from the white culture” (44). Murouwwa appreciated the richness of African culture yet simultaneously denied its lineages by using the term “‘abeed” to refer to all black African men, women, and their children.

The incessant use of the degradation ‘abeed reflects how Murouwwa saw African men and women primarily as bodies of labor to be exploited, inscribing their “subservience” as a class of people vis-à-vis Lebanese Syrians. He uses the female equivalent of ‘abeed, “‘abdaat,” to refer to all black African women when claiming that Lebanese men were “forced to live with ‘abdaat.”80 He persists in using this derogatory term even though he acknowledges that these West African women were wives, conjugal partners, mothers, caretakers, and house managers, and were a lifeline to Lebanese Syrians migrants in West Africa. He writes, “Africans raise at least around half of our migrants’ sons and daughters” (288). In Senegal, many of these women would have been Muslim—and yet Murouwwa barely even acknowledged this similarity. His brazen racializing of African women depicted solely as bodies of labor to serve Lebanese Syrian households either in sexual, caretaking, or reproductive capacities highlights his own racial and gendered insecurities. In Lebanon, historically Shi’i women performed similar domestic work, either as house servants or caretakers. As late as the 1960s, young Shi’i woman and girls would be sent from the village to serve wealthier households in Beirut, or they worked in factories or hospitals doing jobs often deemed too unrespectable for Christian or Druze women.81

Furthermore, Murouwwa’s lack of recognition of Muslim African women or any type of affinity that might develop between Lebanese Muslims and West African Muslims reenforced the French colonial idea of “Islam noir” versus “Islam maure.”82 This was an infamous French policy which inspired strict separation between its colonial populations.83 The French imposed such restrictions to avoid racial or colonial blurring in its colonies (and the metropole), especially among African and Arab Muslims. As a result of this fear, French colonial authorities prevented Lebanese Syrian migrants from living in the same popular neighborhoods as locals or praying in the same mosques, and consistently banned several Arabic-language publications.84 Mixing was a problem for Murouwwa too.

Colonial entanglements were racialized, gendered, and classed, and based on the regulation of intimacy and sexual relations as much as the public sphere.85 Murouwwa’s gendered anxieties were at their peak when he addressed the mixed-raced children resulting from Lebanese-West African unions. In Murouwwa’s constellation of contradictory multi-positional racializations, Lebanese African children still carried the mark of ‘abeed but possessed some redeemable qualities, namely their lighter skin color and intelligence. Mixed-race children, whom Murouwwa flatly calls “the slave women’s children” (awlad al-‘abdaat), were the “biggest problem” in “our migrant community” since they were “neglected” (mahmouleen) (289–90). He claimed their fathers did not recognize or know them. Les metissage posed a biopolitical challenge to colonial racial logics as it did for Murouwwa;86 they could not be filtered into neatly bounded categories and thus required prevention all together.

European colonization of Arabs, Africans, and Asians created the need for racialized hierarchies to justify colonization.87 As Moses Ochonu argues, “The contention is not that Arabs have always been racist against black Africans,” but rather that “once the Saharan and Indian Ocean slave-trades took root . . . there was a persistent need not just for generating but also for reinforcing the racial justifications for them.”88 Ochonu is claiming this for Ibn Khaldun’s era, and I would add that this applied to the late nineteenth and early-to-mid-twentieth centuries under the age of empires as well. Inspired by his European contemporaries such as Charles Darwin (and new readings of Ibn Khaldun), Murouwwa produced religious, sociological, and ethnological claims of “Arab superiority” and “Black inferiority” in the context of colonialism and subjugation.89

CONCLUSION

Upon their return from West Africa, the ‘Amiliyya Association had raised more money than they could have imagined, allowing them to build a large school in the heart of Beirut that remains standing. Murouwwa had also gained many contacts among the Lebanese in West Africa who became the seed funders for his newspaper, Al-Hayat.90 He would visit Senegal again in 1946 to raise money from some of the most successful Lebanese (Shi’i) expatriates to fund his new newspaper. During this trip, he wrote to his sister Dina, in December 1946, “I cannot explain to you the care and attention these brothers have shown me [here]. Each one of them considers himself my brother and responsible for me and my comfort.”91

Murouwwa was assassinated in his office in 1966 at the age of fifty-one in what was believed to be a plot linked to then-president Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt. Murouwwa vocally opposed Abdel Nasser during a period when the Egyptian president’s popularity was unprecedented. He had written an op-ed in Al-Hayat mocking Abdel Nasser, saying if he was strong enough to eliminate Israel then there was no reason to wait, and it would be better to save the Arabs of Abdel Nasser’s empty “Antar” speeches.92 On the day of Murouwwa’s assassination, Senegalese president Leopold Sedar Senghor was in Beirut and asked to attend his funeral.93 Senghor's attendance was deemed unsafe because of the nature of Murouwwa’s death, yet his desire to pay his respects underscores how Murouwwa became a high-profile figure in Lebanon and among the political elite in West Africa. In a recent short documentary made about Kamel Murouwwa’s life, it recast him as an anticolonial figure—at odds with his writings in the 1930s.94

Nahnu Fi Ifriqiya illustrates how the formation of racial identity among Lebanese Shi’is in West Africa was anchored in what Ghenwa Hayek explains as the “relationship between two peripheral spaces, Lebanon and Africa.”95 For Lebanese Shi’is to transition from “uncivilized” to “civilizer,” Africa became fixed, frozen in time and space, singularly defined by “blackness.” While Murouwwa’s travelogue offers multilayered racializations, his understanding of the way racialization moved under French colonialism remained anchored in a black/white, uncivilized/civilized binary. Lebanese Syrians’ approximate whiteness in contrast to African perceived blackness provided tangible benefits in the African context which were not available to Lebanese Shi’is in French mandate Lebanon.96

To bring us back to the opening images of Murouwwa, his “whiteness” and that of Lebanese Syrians only became possible in West Africa in Manichean opposition to the totalizing “blackness” with which Murouwwa contrasts it. His role as an approximate “colonizer” became plausible only in juxtaposition to the “savage native.” For Murouwwa to be white, all Africans had to be ‘abeed; for Murouwwa to be colonizer, all Africans had to be “savage.”

Through Kamel Murouwwa’s travelogue, we can observe how Lebanese Shi'is visitors to West Africa began to perceive themselves in racial terms within the colonial order, and how this perception changed from Lebanon to West Africa, disrupting fixed colonial categories defined by geography. Sectarianism carries significant weight within the confines of the nation-state but a broadened transnational approach to sectarianism provides a widened view to see how racial identity supplanted sectarian identity outside the nation-state and how those racial ideas circulated back to Lebanon. Understanding the interplay between race, sectarianism, and colonialism in the Lebanese context is essential for understanding the development of racial identities in the Middle East and North Africa and sheds light on the ways in which colonialism shaped identity formation in the region.