Olga Verlato

CHILDREN IN THE ARCHIVE: MIGRATION AND SCHOOL LIFE IN TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY EGYPT1

Abstract

What happens when we approach children and youth as the

producers of their own history? This article foregrounds the concrete

traces left by children and young students in the historian’s archive in

order to offer an exploratory investigation of how they participated in

the multifaceted history of transnational and internal migration in late

nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Egypt. I focus on children and

young individuals who, on the one hand, belonged to migrant communities

in Egypt and, on the other hand, produced narratives which spoke to the

experience of transnational and internal migration. By examining school

exams, letters, and petitions produced by pupils between the 1880s and

the 1920s, I reconstruct how younger members of society engaged with

various forms of parental, communal, and state authority and support as

they moved across different social, legal, and spatial geographies.

خلاصة

ماذا يحدث عندما نتعامل مع الأطفال والشباب باعتبارهم منتجي تاريخهم؟ يسلط هذا المقال الضوء على الآثار الملموسة التي تركها الأطفال والطلاب الصغار في أرشيف المؤرخ من أجل تقديم تحقيق استكشافي لكيفية مشاركتهم في التاريخ المتعدد الأوجه للهجرة داخل وعبر الأوطان في أواخر القرن التاسع عشر وأوائل القرن العشرين في مصر. أركز على الأطفال والشباب الذين، من ناحية، ينتمون إلى مجتمعات المهاجرين في مصر، ومن ناحية أخرى، أنتجوا روايات تتحدث عن تجربة الهجرة العابرة للحدود الوطنية والداخلية. من خلال فحص الامتحانات المدرسية، والرسائل، والعرائض التي قدمها التلاميذ بين ثمانينيات القرن التاسع عشر وعشرينيات القرن العشرين، أعيد بناء كيفية تعامل أعضاء المجتمع الأصغر سنًا مع أشكال مختلفة من السلطة والدعم الأبوي والمجتمعي والدولي أثناء انتقالهم عبر مختلف المجالات .الاجتماعية والقانونية والعسكرية. الجغرافيا المكانية

INTRODUCTION

What happens when we approach children and youth as the producers of their own history? Historians of the modern Middle East including Beth Baron, Benjamin Fortna, Omnia El-Shakry, Lisa Pollard, Heidi Morrison, and Tylor Brand have examined the evolving role and experiences of children in society, and the emergence of new conceptions of childhood in keeping with state-building efforts, nationalist and anti-colonial movements, and social reforms.2 In keeping with the rise of childhood studies in the humanities, these works have provided invaluable insights into the history of gender and the family, pedagogy, medicine, and childcare and child-rearing in the region. Yet there still remains a tendency to focus primarily on the perspective of the adults and organizations that interacted with children and youths, such as teachers, charitable societies, and political authorities; or of the children’s “future selves” as detailed through memoirs and in literature.

Engaging with the call of, among others, Nazan Maksudyan to “regard children as legitimate witnesses to construct a new history,” in this article I examine the concrete traces left by children and youths in the historian’s archive in the form of exams, letters, and petitions. I complement these direct accounts by foregrounding children’s perspectives as these emanate from adult-produced archival documents, thus going beyond an attempt to, as scholar of childhood Sara Maza put it, “locate child-generated sources and recapture the agency of the very young” for its own sake.3 I follow Ishita Pande’s invitation to draw on the insights of scholars of colonialism, race, and gender to approach critically the colonial archive and seek to produce a history not only by but also through children.4

In line with this issue’s guiding theme, this article focuses on children and young individuals who, on the one hand, belonged to migrant communities in Egypt and, on the other hand, produced narratives which spoke to the experience of transnational and internal migration.5 I thus aim to offer an exploratory investigation of how children and youths participated in the multifaceted history of transnational and internal migration in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Egypt as they embraced, mobilized, or contested dominant narratives around migrants and children, and navigated various forms of parental, communal, and state authority.6

I examine transnational and internal migration under the same analytical framework for a number of reasons. First, the experiences of Egyptian and foreign migrants oftentimes shared common characteristics when it came to, for example, the struggles and opportunities of geographic relocation, community and identity building, and political or social precarity. Second, and most crucially, historians have found “connections between local and transnational movements. For international migrations have local origins,” as David Feldman put it.7 And, we may add, international as well as internal migrations have local destinations. Whether pertaining to the movement of foreign or Egyptian children, all the sources examined in this article have one thing in common: they were produced in or addressed to authorities centered in the main Egyptian cities of Cairo and Alexandria. Some of the key processes behind the movement of children and their families to these locales at the time, the “social conditions or regimes of motion within which different types of migratory figures emerge and coexist,” were in fact linked to one another: the search for employment, including in the numerous construction and infrastructural projects that were underway at the time, commerce, and the increase, although still limited, of state and private educational opportunities.8

After providing some context on the history of migration in Egypt in the period under consideration and reflecting on the methodological and analytical challenges of working with children’s archival accounts, part I of the article zooms in on the case of Augusto Masini, a fourteen-year-old Italian orphan and Alexandrian resident, who in 1893 petitioned the Egyptian Minister of Education to obtain an extension of his allowance and cover his school fees. Masini’s case provides an entry point to discuss some of the overlapping forms of authority that European migrants in Egypt, and migrant children in particular, were subject to and attempted to navigate to secure their wellbeing and access to education. Part II turns to the comparatively underexamined history of internal migration within the Egyptian territory, as seen through a single exam penned by secondary-school student Muhammad Saʿid Yusef, which recounted the experience of studying far away from one’s home and family. In part III, I discuss how foreign and local authorities instrumentally portrayed migrant and Egyptian students as the ultimate mirror of society, in keeping with evolving notions of national and communal belonging in the early twentieth century. Yet at the same time, as I show, students were able to strategically tap into these official discourses to advance their own objectives.

SCHOOLING AND MIGRATION

The history of migration in modern Egypt has received considerable scholarly attention, alerting us to the vastly different kinds of mobilities that individuals experienced and were subjected to. Intellectuals and professionals, working-class individuals, political dissidents, and peasants were only some of those who came to Egypt from other Ottoman provinces, North Africa, and Europe in this period, and to Egypt’s main urban centers from other parts of the country. Numerous scholars including, most recently, Lucia Carminati, Khaled Fahmy, and Will Hanley have shed light on the uneven spaces of social, legal, and cultural interaction and discrimination that were inhabited and shaped by these migrants and their communities, chiefly in a context in which European nationals continued to enjoy legal privileges that excluded the vast majority of the local population.9

Education is a key domain in which to explore the experience of those who, among these migrants, were children and young individuals. As Donald Reid, James Heyworth-Dunne, Beth Baron, and Hoda Yousef, among others, have shown, the late nineteenth century was a phase of profound transformation in the educational environment of Egypt. With the beginning of the de facto British occupation in 1882, the Egyptian Ministry of Education proper was abolished, and schools started to be administered through a department, called Nizarat al-Maʿarif, within the Ministry of Public Works. At the same time, the number of schools and students increased at both the elementary and higher levels, even though the overall literacy rate remained low (in 1917, 29 percent and 6 percent of school-age boys and girls, respectively, received formal education).10 In addition to the kuttabs (traditional village or neighborhood schools), there were also Egyptian state schools as well as foreign schools run by charitable and missionary associations, foreign colonial authorities, and schools established by private individuals or community groups. Italian schools, for example, catered to one of the largest foreign communities in the country, with around 35,000 individuals by the early twentieth century.11

Not only were these foreign communities internally diverse, as Lucia Carminati recently elucidated, but they were also not hermetically siloed from the local population and other migrant groups.12 For example, Italian students such as Augusto Masini could be enrolled in Egyptian state schools. During the 1906–7 academic year, 43 Italian nationals reportedly attended Egyptian schools in Cairo, out of a total student body of 23,544, while, for example, 86 Greek pupils were enrolled in Italian ones out of 1,435 total students. In turn, Egyptian pupils attended foreign schools, including but not limited to missionary schools, alongside their non-Egyptian classmates. Out of a total of 11,486 students enrolled in foreign schools in Cairo during the same academic year, 5,484 (nearly 50 percent) were reportedly Egyptian nationals.13

Egyptian educational authorities used a series of terms to refer to children and students of different ages. It is not my goal here to offer a comprehensive overview of conceptions of childhood in turn-of-the-century Egypt. For the purposes of the present analysis, however, it might be worth briefly mentioning some of the most common terms employed by state officials and scholars at the time to refer to children and students. In 1917, prominent Egyptian historian and former school inspector and school director Amin Sami (1857–1941) defined sin al-taʿlīm, or “educative age,” as running “from age 7 – age 15.”14 On occasion, physiological indicators such as the development of teeth could be used to determine the age and physical development of a child. For example, in 1858, a certain Abd al-Qadir, son of a late Alexandrian merchant, was described in correspondence between the Alexandrian Governorate and al-Maʿiyya al-Saniyya (Vice-Regal Cabinet) concerning his admission to the Military School as having lost most of his baby teeth (fāqid al-asnān wa baʿaḍ al-‘aḍrās) and as being ten and, in one missive, eleven years of age. In turn, the fact that Abd al-Qadir had a “good constitution” (salīm al-bunniyya) and “some knowledge of reading and writing” (dirāya bi-l-qirā’a wa al-kitāba) was emphasized in discussions on whether to admit the child to the school.15

It thus appears that a combination of physical and intellectual characteristics, rather than age alone, could be used to determine the appropriateness of a child’s access to educational provision, especially in earlier decades of the nineteenth century. It is also worth noting that when it came to young Abd al-Qadir, the very reason why we know about his plea—namely that an adult, in this case his mother, had brought it before the authorities—was likewise crucial to his chances of admission to the school.16

Children and youths were also categorized based on the level of schooling they attended in ways that transcended age. While children and teens were generally referred to as al-banīn wa al-banāt (boys and girls) in the context of education, the term talāmidha (students) was commonly used for students in elementary and primary schools, while ṭullāb (also meaning “students”) appears to have referred more often to students enrolled in higher-degree schools regardless of age. The absence of a relatively stable correlation between students and age was also linked to the fact that in this period, primary schools were not necessarily attended (only) by individuals whom we might think of today as children. Well past the turn of the century, it was not uncommon for older students in their teen years to attend primary school after having acquired a degree of literacy in a kuttab, a local elementary school, or privately.

The standard term for child, ṭifl (pl. aṭfāl) was often employed to refer to children when it came to matters of child-rearing, parenting, and health more so than in the context of formal education. In turn, ibn, meaning son (pl. abnā‘), was used in political discourse, official correspondence, and to express patriotic sentiments, for example when referring to abnā‘ al-waṭan (“children of the homeland”).17 The term walad (also meaning child or son, pl. awlād) was sometimes employed to differentiate between individuals of all ages from allegedly distinct ethnic or national groups, as in the case of awlād al-ʿarab and the Ottoman-Turkish evladɩ Arab (literally “children of Arabs,” used to refer to Arabic-speaking Egyptians).18 As we will see, adult authorities also distinguished between children or teens based on contingent factors and their own specific goals, such as, for example, when wishing to emphasize the vulnerability and child-like status of a young teen or, conversely, depict a boy as a threatening, nearly adult individual.19 Finally, the children and young students who produced the sources analyzed in this article also described themselves differently (if at all); for example, as a “student” (tilmīdh), “orphan” (orfano), and “the poor” (al-faqīr).

Emphasizing the existence and coexistence of these different terms depending on age, physiological attributes, political projection, social status, and educational level, or a combination thereof, contributes to an attempt on the part of many historians of childhood to treat this category not only—or not at all—as a biological and universal condition but first and foremost as a historically produced construct. This move is fruitful insofar as it allows us to explore in what ways, why, and at which historical junctures a specific terminology found prominence, was developed, or came into disuse.

BRINGING CHILDREN OUT OF THE ARCHIVE

Children and younger individuals do not usually leave many traces in the historian’s archive, at least compared to adults. Moreover, even seemingly “direct” accounts such as those examined in this article are, to various degrees, mediated sources that were reported in official correspondence, publications, and educational surveys. Many of these sources, finally, tend to appear apolitical and “mundane” on the surface. In keeping with these analytical and methodological constraints, and engaging with the invitation by historians of childhood such as Ishita Pande and Robin Chapdelaine to “read mediated records against the grain to recuperate the faintest of whispers” and “accept the glimpses that are available, even when intent or impact . . . cannot be fully argued,” in this article I approach the sources produced by children and young individuals as responses or alternatives to the normative discourses that sought to frame them.20

Because of the nature of children and young individuals’ social experience in the specific context I examine—one characterized by profound reforms and centralization attempts in the educational domain—and due to my reliance on state archives (rather than, for example, private collections), all the sources I analyze pertain to school life, and some of them are authored by relatively older students. The domain of education was one in which children, and students more broadly, were more firmly positioned to engage with and respond to official narratives through lasting written accounts. Other spheres of political and social life such as the press, law, and political debates, while also producing powerful discourses about children, remained largely the prerogative of adult-to-adult interactions. I thus employ a capacious definition of children that encompasses a range of different ages, including teenagers. The young individuals who produced the sources analyzed in this article range from fourteen-year-old Augusto Masini (part I) to Muhammad Saʿid Yusef, a secondary-school student in the teachers’ training college of Abd al-'Aziz (part II). In addition to being a product of the aforementioned limitations in procuring direct accounts from younger members of society, this capacious understanding of children and youths is also interconnected with the plurality of ways in which children and students were referred to at the time, often without a uniform correlation to age, as noted in the previous section.

The role of the youth and older pupils in modern Egypt has been examined by a number of scholars. Hoda Yousef, for example, discussed how students engaged in direct political participation through the medium of petitions in the lead up to the 1919 anti-colonial nationalist revolution.21 However, these studies tend to focus less on children or younger pupils than on older students who largely considered themselves as part of a new generation framed as “the youth” and as active contributors to political change. At nineteen years old, Mustafa Kamil (1874–1908, one of the most prominent anti-colonial activists of modern Egypt), while admittedly quite young in age, nevertheless presented himself as belonging to an emerging, newly self-conscious section of society associated with youthfulness and the nationalist struggle.22 Instead, by foregrounding seemingly apolitical sources produced by children and young studentssome of whom might well have been around the same age as Mustafa Kamil as he began to engage in political actionmy article seeks to recuperate some of the hitherto underexamined, mundane experiences of children and youth.23 In particular, I am interested in reconstructing the different and overlapping forms of transnational and internal migration and mobility that characterized children and youths’ lives in turn-of-the-century Egypt.

PART I: CHILDREN, MIGRATION, AND THE RHETORIC OF DEPENDENCY

In 1893, the case of a fourteen-year-old Italian boy named Augusto Masini was brought to the attention of Italian consular authorities in Alexandria. The Italian consul in the city noted how “young Augusto” (il giovane Augusto) had been receiving a pension from the Egyptian government ever since the death of his father, the late Edoardo Masini, who had been employed as a police inspector for the Egyptian government. Recently, the boy had been admitted to the Khedival School of Arts and Crafts in Cairo (Madrasat al-ʿAmaliyyat).24 However, after he had turned fourteen, he had lost all support from the Egyptian state and was thus unable to cover the school fees necessary to enroll in the institute.25

To find a solution to his situation that would allow him to continue studying as well as “provide for his personal needs,” Augusto proceeded to send a petition to the Egyptian Minister of Education.26 Written in Arabic and reportedly translated in Italian at the benefit of the consular authorities that were following Augusto’s case, the actual petition was not included in the official correspondence on this matter. All we know is that, in the letter, Augusto highlighted the services that his father had offered to the Egyptian government, his condition as an orphan, and the dire circumstances in which he found himself.27 It might not come as a surprise that Augusto had written in Arabic to the Minister of Education, given that he had been admitted to an Egyptian professional school which required a degree of proficiency in this language. At the same time, his linguistic choice contributed in and of itself to the letter’s rhetorical objective of interpellating Egyptian authorities. Augusto thus leveraged his position as a dutiful student and grateful, dependent subject through his rhetorical and linguistic choices in order to appeal to the state and secure financial support.

The interaction between the young Italian boy and not only consular but also Egyptian authorities illuminates the imbrication of the condition of being a migrant and a child through the notion of dependency. On the one hand, this case reveals a direct association, on the part of political and legal authorities at the time, of childhood with dependency on external support (in this case the Egyptian state), and of coming of age with the ability to perform labor, and thus with the loss of said support. Like elsewhere in this period, the expansion, if limited, of educational provision in Egypt meant that a higher number of young individuals continued to be dependent on familial, communal, or external provision even as they became widely regarded as able to perform labor and provide for themselves.

On the other hand, as Sara Maza has noted, “just as adults in situations of dependency . . . have often been infantilized, older children who attain autonomy through wages and removal from the parental household become adultified.”28 Migrants have often figured among such “infantilized adults,” with nativist discourses and policies depicting them as a potential “burden” on society.29 To be sure, many European migrants in Egypt in the period under consideration inhabited privileged social and legal spaces and were not at the receiving end of this discriminatory rhetoric. More so than his belonging to a migrant community, it was Augusto’s condition as a young orphan that accounted for his condition of dependency and struggle to secure the resources to provide for himself. At the same time, Augusto’s liminal position allowed him to make claims upon both Italian authorities, in virtue of his family origins, and the Egyptian state, due to his father’s professional position.

Children who belonged to migrant communities and the local population and authorities were not necessarily siloed. As Will Hanley has shown, in this period, individual identification relied on a plurality of categories (including residence, occupation, origins, and mobility), while nationality was not necessarily the dominant form of affiliation to manage mobility and diversity.30 Thus, the young Augusto, who had been entitled to (financial) protection and support on the part of the Egyptian state, and had been admitted to an Egyptian state school, continued to regard Egyptian authorities as the primary body responsible for his well-being and social and professional mobility through higher education. He did so, moreover, not only while being categorized a young child by the statewhich determined that support be offered until the age of fourteenbut also after the term of his mandated allowance had expired, potentially challenging the state’s definition of childhood protection in relation to age when it came to education.

PART II: IN PRAISE OF SUMMER VACATIONS

The history of migration in modern Egypt encompassed a second dimension, that of internal, largely rural migration within the Egyptian territory.31 We still know comparatively little about the “thousands of migrants” who, increasingly since the 1870s, moved to the country’s main cities, in particular Cairo and Alexandria.32 Through the work of Zeinab Abul-Magd and Stephanie Boyle, for example, we hear of the Upper Egyptian farmers who, having had their lands seized, cried out in 1911, “We suffer from hunger, our children become orphans . . . and we are forced to migrate;” and learn about how “the vast majority of people residing in the Delta were peasant farmers, many of them émigrés from the south.”33 Meanwhile, Samah Selim closely examined the emergence of nationalist literary representations of the village and the peasant or fellah since the first decades of the twentieth century, following enduring “dizzying rural migration.”34 The expansion of education throughout the nineteenth century, particularly through a series of reforms undertaken by Khedive Ismaʿil Pasha (who ruled between 1863 and 1879) during the 1860s and early 1870s, contributed to the internal mobility of individuals, including young students pursuing their education in larger cities. A single school exam penned in 1907 by secondary-school student Muhammad Saʿid Yusef offers a rare insight into the shifting geographies of education at the time as experienced by students themselves. Before turning to the content of this source, however, it is worth discussing the circumstances in which it was produced and preserved in the archive, as indicative of the ways in which educational authorities conceived of children and education in this period.

As the number of schools and students in Egypt increased around the turn of the century despite dramatic cuts to educational spending under the British occupation, so did attempts by state authorities to monitor education. The employment of a systematizing and controlling modality of knowledge production seeking to define, categorize, and scientifically understand the development of education profoundly shaped how Egyptian authorities managed schools in this period. This, in turn, was part of a broader approach to governance on the part of the Egyptian state. As Timothy Mitchell and, more recently, Khaled Fahmy demonstrated with respect to the fields of medicine, law, and urban development, in the nineteenth century the Egyptian state developed several techniques to “touch and control the bodies of its subjects,” including statistics, the census, cartography, and tables.35 Hoda Yousef, among others, has emphasized the novelty of this phenomenon, arguing that “whereas earlier nineteenth-century attempts to gather information were part of a ‘policing’ of sorts (to determine who owes the government what), the aggregation of data displayed another type of discursive power: the use of statistics.”36

Alongside medicine, the military, and urban development, education was another field that made extensive use of systematizing and monitoring tools, such as standardized examinations. The Egyptian state archives and those in Europe relating to Egypt hold hundreds (if not thousands) of pages filled with charts, tables, lists, and maps on the schools of Egypt from this period, preserving and storing information in a way that ranges “from the fascinating to the mind numbing,” to borrow historian Benjamin Fortna’s characterization of the wealth of documents on education found in Ottoman archives during approximately the same historical period.37 The seemingly neutral act of counting students, schools, and exam results year after year, producing a wealth of cross-referenced snapshots of education (whether based on gender, religion, age, percentage of enrollment against the population, or other categories) exemplifies the widespread belief held by the authorities, Egyptian as well as foreign, that the successes and failures of specific educational initiatives should be understood, and in turn fixed, by means of scientific measurement. Possibly, it was education’s nature as a “inherently temporal project” aimed at shaping future generations and, with them, society at large that made the use of these strategies of categorization and control particularly widespread.38

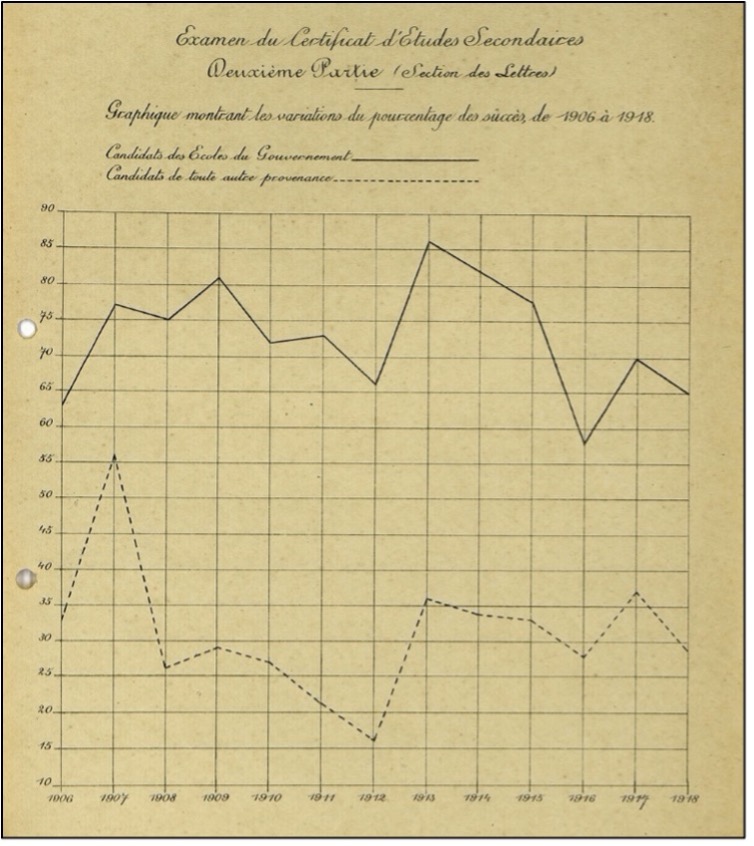

Variations in the success rate of, for example, students taking the secondary school exam in Egypt over several years was represented as a scientific and measurable phenomenon in a report to the Ministry of Education as a way to identify the best modality of pedagogical intervention (fig. 1). Approached and presented in this manner, the information that exams were set to convey was limited to the raw grade number or pass/fail dichotomy. On some occasions, written and oral exams’ performances were also surveyed by inspectors to gain insight into the success of specific pedagogical approaches, such as the degree of reliance on memorization as opposed to reasoning. Yet even in these cases, the actual content of the exams appears as having been of little interest to state authorities. This would not always be the case. Starting in the 1920s, for example, progressive educators in Egypt would pay increasing attention to the experience of children in and outside of school, in turn affecting how state authorities monitored students.39 In this earlier period, however, state bodies such as the Ministry of Education, and the British advisors that exerted control over them, mainly approached education as an objectively quantifiable phenomenon, rather than by adopting qualitative, student-centered pedagogical philosophies.40

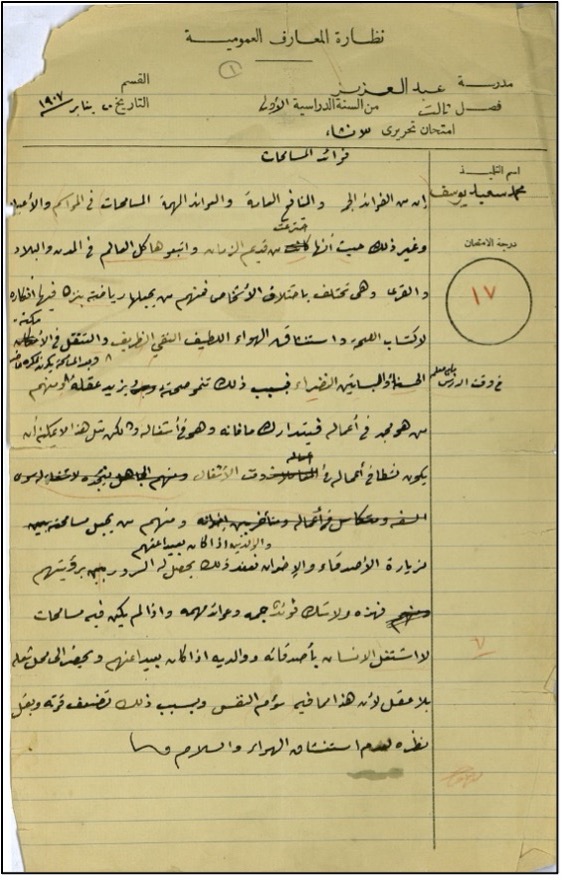

What do exams reveal once their content is analyzed through close reading as a source of information about children and youths’ own perspectives, particularly with respect to the experience of relocating to a different region in the country? To begin answering this question, I turn to what amounted to a mere number lost in a single data point in charts like the one above: the Arabic written composition, dating from 20 January 1907, of Muhammad Saʿid Yusef, a first-year student in the school of Abd al-ʿAziz, in Cairo, a secondary-level teachers’ training college for kuttab instructors (fig. 2).

The exam asked the student to write a composition on the theme: “The benefits of vacations” (fawā’id al-musāmiḥat). It resulted in a grade of 17 (most likely out of 20), despite a number of mistakes made by the student. The composition’s style and content offer some illuminating insights into Muhammad’s engagement with his experience at school, his relationship to peers and family, as well as the pedagogical and writing norms imparted to pupils at the time. From a stylistic perspective, the composition was quite repetitive and used strings of synonyms which, while not uncommon in Arabic prose, nevertheless seem to indicate an attempt to lengthen the text and fill the page. The opening sentence “among the ample benefits, the general advantages, and the important boons of vacations” (min al-fawā’id al-jamma wa al-manāfiʿ al-ʿāmma wa al-ʿawā’id al-muhimma), for example, was repeated nearly verbatim towards the end of the exam. Common rhetorical expressions were also present, such as “in the cities, territories, and towns” (fī al-mudun wa-l-bilād wa-l-qurā).

In terms of content, the composition identified three main kinds of benefits associated with vacations: playing sports and enjoying the open, salubrious air; catching up with work; and visiting friends and family. As Wilson Jacob has noted, sports and physical education were increasingly put at the center of education in Egyptian state schools from the 1870s onward.41 The importance of, on the one hand, sports and physical activity (al-riyāḍa) and, on the other hand, the exposure to fresh air (al-hawā’ al-laṭif) were common topics in the press when it came to discussions of child-rearing and education in this period.42 Both tropes also appeared in Muhammad’s composition, which noted how in the absence of physical activity and clean air, a student’s “strength weakens” (taḍʿuf quwatuhu). Finally, Muhammad noted that vacations allowed a student “to visit friends, siblings, and parents (al-asdiqā’ wa al-ikhuwān wa al-wālidayn) in the case that he lives far away from them, pleasing him to see them.”43

I have not been able to locate the textbook assigned in the Abd al-ʿAziz school at the time of Muhammad’s exam to see whether it resembled a reading assignment or exercise featured in it. Crucially, however, an article titled “Al-Asatidha wa-l-Talamidha fi Awqat al-ʿUtla al-Sayfiyya” (Students and teachers during the summer break) published in 1900 in the newspaper al-Jamiʿa (established in 1899 in Alexandria) mentioned some of the benefits of vacations identified by Muhammad. It also listed several more, such as recovering from the effort of studying and teaching, and learning the difference between activity and rest.44 The similarities between this article and Muhammad’s exam thus point to the existence of a relatively solidified rhetoric around school vacations in this period.

Following Muhammad’s straightforward account of the benefits of vacations for different individuals, the composition elaborated on one aspect in particular. “If there were no vacations, people would not repair to their friends and parents in the case that they live far away, and they would go to their place of work with their mind elsewhere (bilā ʿaql), causing weariness.” That having vacations and free time was necessary to working and going to school was a relatively common trope, as evidenced by the fact that the aforementioned article in al-Jamiʿa mentioned “return to family life” among the benefits of summer vacations, especially in boarding schools (al-madāris al-dākhiliyya).45 Furthermore, along the lines of the opinion that Muhammad expressed, the article in al-Jamiʿa claimed that after vacations, students and teachers “returned to their schoolwork more active and excited about it.”46

Crucially, the third point in Muhammad’s composition, that of the benefits of being able to visit faraway family and friends, directly speaks to the little-explored history of internal migration in connection to education in modern Egypt. Before the nineteenth century, it was not uncommon for children and young students to travel away from home to be enrolled in school in other cities, such as al-Azhar in Cairo, after having studied in local schools including the kuttabs. This trend endured during the period of systematization and centralization reforms of education since the 1820s. In the earlier part of the century, particularly under the reign of Mehmed Ali Pasha (who ruled between 1805 and 1848), children were reportedly “taken” for provincial elementary and village schools in order to be enrolled in the pasha’s new schools.47 During and following the reign of Khedive Ismaʿil, numerous state schools were opened across Egypt’s various districts and provinces. In theory, the opening of schools in different parts of the country meant that students needed to relocate less often in order to receive a formal education.

At the same time, the general expansion of education throughout the century, which was accompanied by a growing desire on the part of parents to enroll their children in school, was not necessarily matched by the opening of a sufficient number of schools, in particular state primary and, even more so, secondary schools. This fact might explain why the phenomenon of students traveling to other parts of the country in order to be enrolled in schools endured well into the nineteenth century and beyond. Boarding schools, for example, continued to operate, catering to both students from the school’s area as well as those from other cities and regions. Moreover, as more and more migrants from rural areas relocated to urban centers, the number of their children enrolled in new state schools also increased.48 Yet how did students themselves experience moving to a different city?

Given that the history of internal migration is still comparatively underexamined, accounts such as that of Muhammad are all the more valuable. Once they are approached in their own terms, exams can reveal much more than a general tendency in students’ success rate or adherence to pedagogical norms, as these were being largely treated by educational authorities. Rather, they partook in broader discourses which scholars often associate exclusively with adult intellectual domains such as the press. On the one hand, the statements in Muhammad’s composition testify to his attunement to widespread tropes about education and school life as found in the press at the time, for example in al-Jamiʿa. On the other hand, his insistence on connecting summer vacations to being able to visit parents, siblings, and friends, avoiding a situation in which students would return to school “with their mind elsewhere” points to the existence of an intimate concern with the hardship of school life away from home. Students’ testimonies can help us bring to the fore key trends in the history of modern Egyptian education that are otherwise muted in official narratives. In particular, in contrast to the dominant scholarly focus on the main urban centers of Cairo and Alexandria as compared to the Egyptian peripheries, Muhammad’s exam allows us to shed light on the centrality, in the experiences of students, of internal migration and relocation, and the longing that could come with it.

PART III: MIRROR OF CHILDREN

A concern with ordering and scientifically monitoring education was a prerogative not only of the Egyptian state but also of consular officials regulating the life of migrant communities. Italian authorities, for example, sought to standardize educational provision, even though crucial differences between schools depending on their typology, financing, location, and local socioeconomic factors continued to exist.49 Local and foreign officials were not only invested in regulating how education functioned on the ground, but also in the potential for schools and the students enrolled in them to in turn represent the community at large. Annual examinations, school ceremonies, and students’ attendance to formal events were important symbolic events in Egyptian state schools across the country (fig. 3). Provincial and state representatives were also often invited to attest to the students’ success.50 For example, it was not rare for ʿumdas (head of the village) to preside over final exams.51 In November 1879, on the occasion of the inauguration of a new school in Cairo under the auspices of the new khedive Tawfiq Pasha (who ruled between 1879 and 1892), a day-long public event was organized which included activities such as pigeon and target shooting, music performances, a buffet, and, at midnight, a “grande surprise.”52 Rawdat al-Madaris, the publication of the Egyptian Ministry of Education established in 1870, featured numerous speeches, including some pronounced by students, on the occasion of final examination ceremonies, which were delivered before both local and foreign dignitaries and emphasized the schools’ contribution to the dissemination of knowledge and sciences among the “children of the homeland” (abnā’ al-waṭan).53

This approach to students’ performances was not confined to Egyptian authorities. While the specific reasons for organizing official school visits and showing off academic excellence varied based on the priorities of different authoritiessuch as the securing of funds for the school by means of inviting prominent local and foreign personalitiesthe underlying interest in children and students as a source of pride for society and the nation was a remarkably common factor across local and foreign communities. Moreover, the use of school examinations, prize ceremonies, and recitals to promote political interests was by no means limited to Egypt in this period.54

Inspections and the surveillance of schools established by migrant communities in Egypt on the part of their relevant governing bodies, such as consular authorities, were directed towards not only pedagogical matters but also the conduct and behavior of students and their role as the ultimate mirror of the “colony” (as European foreign communities were also referred to) at large. Foreign public figures and government representatives were invited to school ceremonies such as end-of-the-year recitals to showcase the students’ abilities and, with them, the community’s worth. To only mention one instance, during the end-of-the-year recital in the Italian International School in Zagazig, in the eastern part of the Delta, in 1899, the students were described by the Italian consular officer in Zagazig Carlo Mazzetti as “filling with pride the hearts of us old Italians.”55

The potential for students’ performances, conduct, and academic success to display the idealized or aspirational image of a given community was simultaneously paired with a deep preoccupation with safeguarding children from what were regarded as corrupting forces and disruptive morals. Whenever the potential for a scandal linked to events unfolding in a school arose, this was regarded as a threat to the good name of the migrant community at large. For example, on 20 March 1900, a certain “Maria V.,” mother of a student in an all-boys Italian colonial school in Cairo, sent a letter to the Italian consul in the city to call his attention to a series of events, left unspecified in the missive, that had taken place in the school. The letter contained a not so veiled threat, and stated, “My husband wants to write about these matters to the newspapers. I do not wish to create a scandal, but I have also written to the Minister of Education in Italy.”56 Maria V. thus appealed to the authorities by leveraging their fear for the reputation of the community, chiefly when it came to its children.

On their part, children and young students in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Egypt were not merely passive receivers of adults’ ambitions and projections but rather spoke directly to political power in order to advance their demands. A key medium through which they made requests was that of petitions. In The Orphan Scandal, Beth Baron noted that children, especially orphans, as well as widowed mothers were among the individuals most likely to petition the state to receive support.57 Moreover, in the lead-up to the 1919 revolution, students’ petitions became increasingly politicized in nationalist and anti-colonial terms, as Hoda Yousef has shown.58

Direct accounts such as the petition penned by Augusto Masini bring to the fore some of the ways in which ideas about the accountability of state authorities towards children and students were articulated and exploited by pupils themselves to their own advantageand in this case, children who belonged to migrant communities in particular. Augusto’s petition, as noted, displayed a degree of proficiency that was itself the product of formal education and the acquisition of a specific know-how in addressing political figures, which constituted a concrete tool to excerpt favorable responses from the relevant authorities. In turn, due to his liminal position as the son of a foreign national who had been in the service of the Egyptian state, the young Italian boy was able to appeal to multiple authorities, both foreign and local.

Egyptian students similarly mobilized official narratives around education as they sought to make demands upon the state, and often did so, crucially, by leveraging a discourse of dependency reminiscent of the rhetoric employed by migrant children such as Augusto. Take, for example, the petition of a certain Muhammad Baqrawi. On 29 August 1916, Muhammad sent a letter to the ruler of Egyptwho at the time held the title of sultan following the promulgation of Britain’s protectorate over the country, which had officially remained, until then, an Ottoman provincein order to ask for support for himself and his family. Muhammad, who lived in the town of Matai in the province of Minya, in Upper Egypt, explained that six years prior, he had enrolled in a local Islamic charitable school. He had passed each year of instruction there except his last, when he failed the primary school certificate examination. Having tried the final exam again, he gained the certificate at last. After his father lost his sight, however, and was unable to pay for the school fees, Muhammad resorted to address no less than the Egyptian sultan asking for support since, he claimed, he was “unable to do any kind of work.”59 Similarly to Augusto, Muhammad thus emphasized his condition of economic dependency. In particular, he highlighted the fact that he found himself in a precarious position despite the fact that he had successfully completed his studies.

In advancing his request, Muhammad deployed various stylistic and rhetorical strategies. The petition included a series of expressions and attributes to describe the sultan that implicitly obliged him to fulfil the request. Muhammad addressed the ruler as “our lord majesty” (jalāl mawlānā) and himself as “the poor” (al-faqīr) at the beginning of the petition as well as in the signature. The overall linguistic register of the petition, written entirely in classical Arabic (fuṣḥā), was quite high. Dates and years were offered in both the Gregorian and Hijri calendars, and the text was structured according to established conventions of petition and letter writing, such as the use of the expression “I present to your majesty the following” (arfaʿu li-jalālatikum ma huwa āt) before the main body.

With respect to the content of the petition, Muhammad emphasized first and foremost his educational career as a way to substantiate his request of support from the sultan. Half of the petition was in fact dedicated to describing Muhammad’s successes in primary school in great detail. “I was a student in the school of the Islamic charitable association in Bani Mazar,” the petition stated. “I enrolled in the school in 1910, corresponding to 1328 hijri, during the preparatory year, from which I moved on to the first, the second, the third, and thereof the fourth [year].” In turn, Muhammad characterized his father’s disease as an unforeseen turn of events (al-qaḍā’ al-maḥtūm, “by inescapable fate”) that had precluded the student’s advancement in his otherwise promising career. In a context in which the education of the younger segments of Egypt’s society was portrayed as an eminent and enlightened objective on the part of political authorities and intellectuals, Muhammad’s revindication of the appropriateness of his own educational path can be seen as being aimed at inscribing himself within the framework of such wider social and political expectations and, consequentially, at substantiating his request for financial support.

When examined together, the archival trails of Augusto and Muhammad bring to the fore some of the similarities in the discursive moves of Egyptian and foreign children and young students, specifically their reliance on a discourse of dependency. Yet at the same time, Augusto’s position as a privileged foreign subject in the country allowed him to appeal to local as well as foreign authorities, unlike what was the case for Muhammad. Possibly for this reason, Muhammad’s petition emphasized first and foremost his record as a successful student to justify what he regarded as his legitimate need to turn to—and depend on—the state. Instead, Augusto framed his need for dependence with reference to his condition as an orphan and continued childlike status past the age of fourteen.

From a methodological perspective, identifying some of the differences as well as shared aspects in the experiences of migrant (both international and internal) and non-migrant children such as Muhammad Baqrawi, Augusto Masini, and Muhammad Saʿid Yusef can help us begin to sketch out a more nuanced history of local and migrant life in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Egypt. Beyond the mere recuperation of children’s voices in a vacuum, the traces that these children and youths left in the archive can complement or even challenge dominant structures and the normative narratives that underlaid them.60

CONCLUSION

In this article, I sought to apply some of the insights of childhood studies to an exploration of the history of migration in modern Egypt, foregrounding the experiences of children and youths as they moved to a different city to pursue their education, or addressed local and consular authorities from a position of social and legal liminality. Childhood studies offers a productive approach to improving our understanding of the history of migration in Egypt—especially if, moving forward, we broaden our focus to include more systematically non-European migrant children. And as is the case with archival sources more generally, when it comes to accounts produced by children and youths, we are confronted with an overwhelming representation of literate individuals. Since with regards to children and younger individuals, the category of “literate” more often than not coincides with that of “students”who, in the period under examination, predominantly belonged to the middle and upper classesit follows that histories of children end up focusing largely on the domain of education, as in the present case. Consequentially, a history by children and through children that is not bound first and foremost by the context of education would need to expand its scope beyond written accounts by, for example, challenging a strict definition of literacy, as in the brilliant study Composing Egypt by Hoda Yousef. While much remains to be explored when it comes to the history of children and migration in modern Egypt, this preliminary study hopefully indicated the importance of reinserting younger members of society in our investigations, regarding them as legitimate and active participants of historical change.