Francesca Ceola

COUNTER-MAPPING AND MIGRANT INFRASTRUCTURES: SOME CRITICAL REFLECTIONS FROM THE “CAMPSCAPE” OF SHATILA, BEIRUT

Abstract

This article questions the notions of refugee and migrant spaces’ formulations and representations by considering the complex of elements which constitute the refugee camp of Shatila, Lebanon, as articulated by the camp residents themselves. Counter-mapping as methodology and analytical lens serves to reveal, convey, and decodify the proliferating meaning-makings of social, political, and economic relations that uphold the everyday life of the “camp,” determine the shapes of its spaces, and signify its materiality. A reticulated structure of care emerges, described by the notion of migrant infrastructures, from which emanates an invitation to reconsider “informality” of places such as refugee camps as rather extremely developed forms of being and asserting presence.

ملخّص

يشكك هذا المقال في مفاهيم الصياغات والتمثيلات الخاصة بمساحات اللاجئين والمهاجرين من خلال النظر في مجموعة العناصر التي تشكل مخيم شاتيلا للاجئين في لبنان، كما أوضحها سكان المخيم أنفسهم. تعمل الخرائط المضادة، كمنهجية وعدسة تحليلية، على كشف ونقل وفك تشفير أشكال المعنى المنتشرة للعلاقات الاجتماعية والسياسية والاقتصادية التي تدعم الحياة اليومية لـ "المخيم" ، وتحديد أشكال مساحاته، والدلالة على ماديته. تظهر بنية شبكية للرعاية، موصوفة بمفهوم البنى التحتية للمهاجرين، والتي تنبثق منها دعوة لإعادة النظر في الطابع غير الرسمي" لأماكن مثل مخيمات اللاجئين كأشكال متطورة من الوجود وتأكيد" .الوجو

INTRODUCTION

The power of maps—as objects with enhancing graphic and visual components—to conceptualize, organize, and represent space is just the departure point for considering what is written, represented, produced, reproduced, obscured, or neglected of and about a very specific place, such as the refugee camp of Shatila, Lebanon. The power of official maps stems from standardizing space through graphic conventions reductive of the composite elements making up a place, with the implication of obfuscating places’ political sensitivity. To contrast this tenet and with specific reference to refugee camps, the research presented in this article joins the wave of counter-mapping experiments, some of which are presented below, as a proposal to upend the binary that characterizes representations of refugee camps within the dialectic: sites of exception at the margins of society that confine, control, and filter, on the one hand; and spaces of active identity formation, empowerment, and resistance, on the other hand.1 This article advances counter-mapping as a theoretical framework and analytical and methodological tool to engage with and divulge the intricacies of camp spaces and lives as narrated from within the camp.

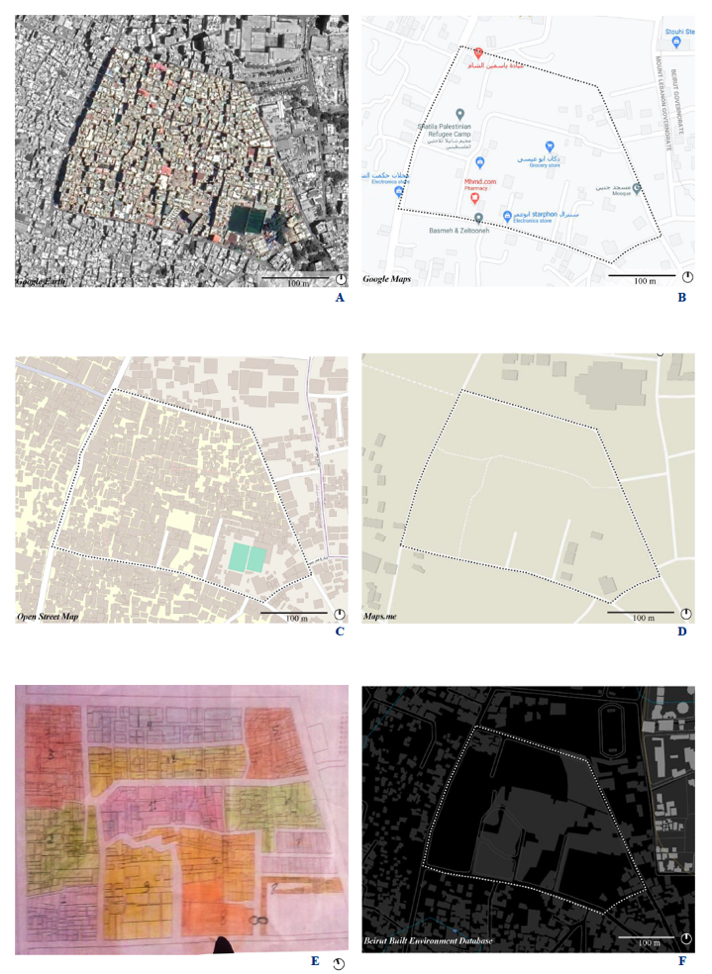

The early history of Shatila is traced back by Rosemary Sayigh to the settlement of refugees displaced from the Palestinian village of Majd al-Krum in 1949.2 This group negotiated access to a plot of land of two hundred-by-four hundred meters with Basha Shatila, the representative of the landlord, the Saad family; the present camp still extends over the same land plot. While the settlement was established south of Beirut at the time, the metropolitan area’s subsequent expansion absorbed the camp within the landscape of urban suburbs. Yet Shatila retains its special character: the extraterritorial exceptionality of official refugee camp status. This designation, serviced by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), renders the camp ambiguously outside the reach of the Lebanese government and allows, arguably, self-administration by internal camp committees.3 Prior to fieldwork, representations and a satellite image of Shatila were collected through online sources (Image 1). The dotted borders of the official refugee camp were subsequently added.

The map images are drawn from a sample of digital mapping databases and platforms, selected according to the criteria of popularity, local relevance (Beirut Built Environment Database for Image 1F is powered by the American University of Beirut), and a mix of open (Open Street Maps [OSM] Image 1C, Maps.ME Image 1D) and closed source (Google Maps Image 1B). The satellite Image 1A is taken from Google Earth and edited to distinguish Shatila through enhanced contrast. Additionally, the printed “official” map of Shatila Image 1E, on display in the halls of different camp NGOs and found in the hands of some Shatila residents, illustrates the subdivision of Shatila’s land plot by color and the demarcation of the main streets and alleys. Although I was shown this image once I was already in Shatila, I find it suggestively contrasts with the other four maps and illustrates the origins of the research: specifically, the low information density in the maps triggered a reflection on representation and spatial in/visibility at work in Shatila. Based on acquired map knowledge, the portion of space represented in the top four images (Images 1A–1D) is quickly read by modern Westernized global viewers as a city area: with no specified place name (except in Image 1B), marked by roads, with a few registered commercial activities in Image 1B (although the NGO Basmeh & Zeitooneh is misplaced), and a scant number of buildings except for the OSM image (Image 1C). The latter also features two green rectangles—the camp’s football fields that will recur later in this article. These graphic descriptions are legible to the viewer,5 yet they show their fictionality when juxtaposed with the satellite image of a dense built environment. Thus, alerted to the power of cartographic images as constructive of emptiness and indicative of worth in representations of “empty” and “unproductive” territories,6 and the self-perpetuation of maps’ “grey blobs” as unknowable places,7 the practice of counter-mapping as an ontological approach, analytical gaze, and methodology presented an important alternative. By emphasizing counter-mapping in Shatila, I hope to illustrate some possibilities for emancipatory representation, refugees’ reappropriation of the agency to ascribe meaning to places, and the latter two’s contribution to the visualization of overlapping territorial processes in Shatila refugee camp.

The paper develops according to the following structure: First, I briefly contextualize the research and fieldwork this article builds on. Then I discuss the salience of mapping in and from refugee camps and inscribe it within the larger critiques of cartography’s relations to power and knowledge. Subsequently, I present the results of mapping with residents of Shatila and elaborate on the emergence of what are understood as migrant infrastructures—micropolitical and spatially determinant organizations engendered by cohabiting multiple communities. The mappings generated by Shatila’s residents suggest that despite the structural marginalization experienced by the camp communities, Shatila’s residents appropriate and re-signify space to meet their own needs in complex and unrecognized ways.

RESEARCH CONTEXT

This article builds on the research fieldwork I conducted for my master’s thesis between 2019 and 2020 within a historical, geopolitical, economic, and current Lebanese context defined by the ongoing mass regional displacement caused by the war in Syria, the looming threat of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the political and economic collapse in Lebanon. The master’s research aimed more broadly to address the heuristic utility of the refugee camp as a spatial figure. I relied on a critical grounded theory approach from the field of geography to question the appropriateness of refugee/forcedly displaced/labor migrants divisions, where the heterogeneity of human situations—socioeconomic, legal, cultural, and historical—coexisting in the camp suggested otherwise. As a refugee camp, Shatila counts on UNRWA support and recognition. Other local and international NGOs also operate in terms of aid and humanitarianism, while two camp committees are the popular representatives regarding politics and administration in the camp. The site occupies a specific place in the Lebanese and Palestinian history of violence,8 and is characterized by an intricate overlapping of migrations.9 Since the beginning of the war in Syria, the migration regulation policies of Lebanon for Syrians have evolved from being completely unrestricted, to one that externalized migration “management” by placing refugees within the exclusive capacity of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), to the omission altogether of the refugee figure displaced by violence. As of 2015, Syrians in Lebanon could only apply for expensive yearly work sponsored visas—delineating a rather bleak legal framework that the authors of the book Refugees as City-Makers consider “manufactured vulnerability.”10 While large parts of the Syrian diaspora settle in formal and informal housing arrangements in the rural areas of Lebanon,11 others resort to seek shelter in long-established Palestinian refugee camps like Shatila, where accommodation remains relatively cheap, the vicinity to large urban centers maintains the hope for opportunities, the risks of eviction and sanctions are obviated, and often preexisting social connections exist.12

The historical and cultural weight of the Shatila Camp has produced no little reflexive questioning as to why and how I was to justify choosing to work with Shatila, especially as this specific place is what Mayssoun Sukarieh and Stuart Tannock assert to be one of the most over-researched communities among the Palestinian diaspora.13 My role as researcher thus risks further exhausting a disillusioned community that has seen no improvements to their condition as a result of their collaboration with countless “researchers” over decades. The simple answer is that Shatila is where I had friends—specifically, members of a youth sports club—who were going to receive me. Moreover, the rapid socioethnic transformations experienced by the camp and its surrounding space make it an extremely dynamic place and community. The generation I mostly connected with through the sports club was born years after the end of the Lebanese wars, and although carriers of intragenerational traumas and of what Hirsch defines as “postmemory,”14 they have grown up with camp constellations and in an unprecedented historical period. Accordingly, the effects of the most recent historical and political regional developments—especially but not exclusively the war in Syria—tackled in this article have perhaps not been exhaustively voiced yet. Confining the locus of the research to a demarcated place thus served to focus geographically rather than selecting one “community.” Specifically, by engaging with counter-mapping as methodology and analytical lens, but also as social and activist practice, it was possible to bring together the heterogeneity of visions of Shatila Camp, reflecting the inhabitants’ diversity and essential individuality.

The literature on camps not only serves as reference for the recognized agency of the refugee figure as well as the micropolitics of space alteration and appropriation at play in refugee camps, but it also acknowledges the blurring of the official established borders of “refugeeness” and the intrinsic limitation of the legal category of refugee. While these reasonings are exposed elsewhere, these introductory thoughts point to the need for a language able to capture complex formations, transcend static analytical categories, and ready to recalibrate its lexicon vis-à-vis ontological developments—where counter-mapping is just one part of a wider epistemological effort of post-categorical thinking.15

MAPPING REFUGEE CAMPS, RETRACING THE POWER OF MAPPING

The salience of mapping refugee camps is testified by the work of multiple projects in Lebanon and elsewhere. Claudia Martinez Mansell and her collaborators reversed the authorship of the cartographic eye in mapping the Palestinian refugee camp of Bourj al Shamali, located in southern Lebanon, by using aerial photography from a red balloon (as opposed to drone technology, which triggers specific sensitivities among residents of Lebanon).16 The researchers assumed that the only existing maps of the camp were held by humanitarian actors who would decline to share them for security reasons. Camp residents were initially reticent about mapping. However, they willingly took part in the mapping process through sharing their rooftops to launch the researchers’ red balloon, thereby reclaiming the power to negotiate the mapping project’s feasibility. While producing the final map responded to the preoccupation that “to live without a map is to exist without a future, in a space forever uncharted,”17 starting conversations about camp residents’ knowledge of their environment was in itself the achievement of this critical mapping project. Also, in Lebanon, the camp population’s involvement was crucial for rebuilding Nahr el Bared refugee camp after its almost total destruction in 2007. Although the Lebanese state contracted a construction firm to design a master plan based on the security paradigm (wide streets navigable by tanks and unfeasible for urban guerrilla warfare), a group of activists and urbanists, organized as the Nahr el Bared Reconstruction Commission for Civil Action and Studies (NBRC), challenged the state’s reconstruction plan.18 NBRC consulted evacuated refugee camp residents when designing a different proposal, which was developed by retracing pre-destruction neighborhood structures, employing social practices, and recognizing property rights.19 In Ayham Dalal’s co-mapping of Zaatari Camp in Jordan, which investigates the dismantling and reassembling of the camp’s sociomaterial structures and memories, Dalal held co-mapping sessions with interviewees in which he sketched residents’ descriptions of the camp’s spatial transformations as well as their reactions to the visualization of the space perceptions and experiences they wanted documented.20 In the West Bank’s Dheisheh Camp—provocatively following the blueprint of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) nomination dossier—with the participation of the camp committee, camp residents, and local cultural institutions, the multimedia project “Refugee Heritage” led by the collective Decolonizing Architecture Art Research (DAAR) documented the camp’s archaeology, planning, and imaginaries that bear decades of physical, social, and political history and memory.21

This minimal sample of refugee camp mapping projects introduces the impulse for counter-mapping refugee camps as drawing from a broad set of practices, knowledges, and technologies that surpass “classic” cartography, its embeddedness in colonial history, its predicaments of scientific rigor and objectivity, and its relationship with power and the latter’s ideologies. Critical accounts of the history, development, and deployment of cartography aim to deconstruct the normalization of the relation between maps and territory in ways I will succinctly present in the following pages. They do so primarily along two interrelated argumentative binaries: questioning maps’ 2D descriptions of the world composed of signs signified by established graphic conventions; and disarticulating the map object from the processes that endow it with recognition for the supposedly objective scientific rigor that has produced the map.22 Addressing the latter point first, maps were central geographic practices utilized by empires for the measurement of resources, dispossession of indigenous lands, privatization of commons,23 and as products of the masculine colonial gaze that embedded land in a visual ideology that commodifies it or transforms it into property—first through landscape painting, then with topographical surveys and cartography.24 Neil Smith sheds light on the assertion of scientific authority implied in maps operated by a dehumanization of the mapping process: the authors seem to vanish, while the map comes forth as object exuding authoritative veracity.25 Smith argues that the geopolitical use of geography departments, in which university administrators (in conversation with state intelligence personnel) directed the cartographic rewriting of war and post-war zones, constitute practices of “the empire at home.” The cartographic activity and underpinning epistemology were also transplanted from the colonial and imperial “centers of calculation”26 to the colonized territories where activities of mapping and surveying were enshrined in myths of scientific coherence and rigor by the imperial representatives. However, the representational construction and subsequently engendered topographical biases are exposed in the documented failures of surveying projects.27 Expanding philosophically, rewriting the cartographies of places and territories operates along the ambivalence of what is marked on the map—visually enhanced—and what is obscured because it is strategically excluded or epistemologically silenced.28 The invitation though is to take these cartographic “silences” as positive statements nonetheless, with the performative power of removing communities and territorial “cosmovisions,”29 in the social construction of specific world views.

The second binary is the graphic codification of a cartographic language, which abstracts the material and symbolic qualities of space and makes them legible through representation conventions that are endowed with scientific reliability. Perspective in painting and Euclidean geometry in bidimensional mappings are just two examples for questioning givens of the visual ideology that produces cartography.30 It is argued that codification through signs, as much as through glossaries of topographies and toponymies, are heuristics that support the legibility of the state or the governing order-logic and their materialization in space.31 Thus, while critical cartographies engaged primarily in exposing the embeddedness of power relations in maps, counter-cartographies emerged as a response to the monopoly on representation that is contended to be upheld by the powerful actors of the mapping sphere. Leila M. Harris and Helen D. Hanzen, for instance, suggest a threefold proposal that counter-cartographies tackle: an epistemological shift, that is the incorporation in the mapping toolkits of multiple knowledge systems relevant to the mapped context; a methodological shift in the hybridization and cross-contamination of mapping language, tools, and techniques; and a democratization of mapping by opening the formerly exclusive domain of “specialists” and returning sovereignty on representation to the mapped communities and territories.32 Mapping thus can become the instance for communities to reappropriate the terms of self-representation33 and of the visualization and assertion of territorial processes, diagnoses, and claims.34 Counter-cartographies build upon an expanded collaboration of fields—arts, academia, and political activism35—to question and reinvent the meanings and practices of mapping. Thus, countering is aimed at contrasting the rhetoric and effects of colonial visual ideologies. But it is also a choice of reflexivity whereby one interrogates the predicaments and implications of mapping practices—the reification of spatial assumption and the performativity of spatial separations and obfuscations. Taking it further, counter-cartographies become counter-mapping when they challenge the predicament of maps as representations. Deconstructing the map object endowed with the power of presenting a representation of reality and re-signifying it as “operative images which constitute the represented and make it possible to operate with it,”36 the mapping process, the discursive practices around it, and the ontogenesis of the represented surface. They become the analytical lens that overturns the meaning of and approach to mapping.37 Importantly, temporal evolution and dimension come to be implied during the mapping process, and the singularity of one map as a representative image of a territory, process, or place is surpassed.38

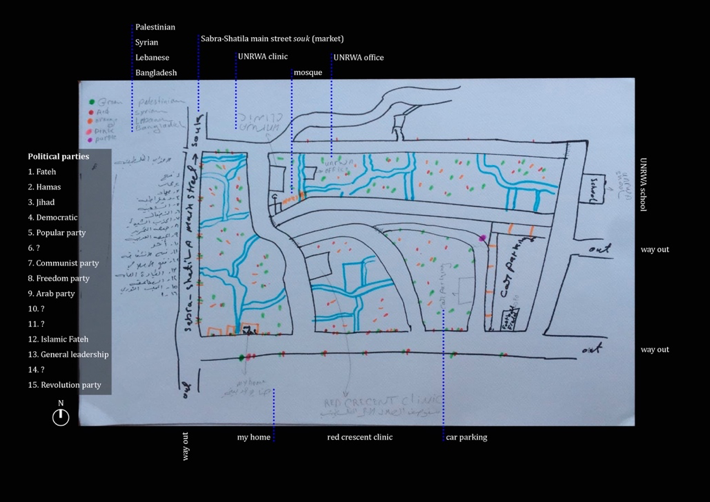

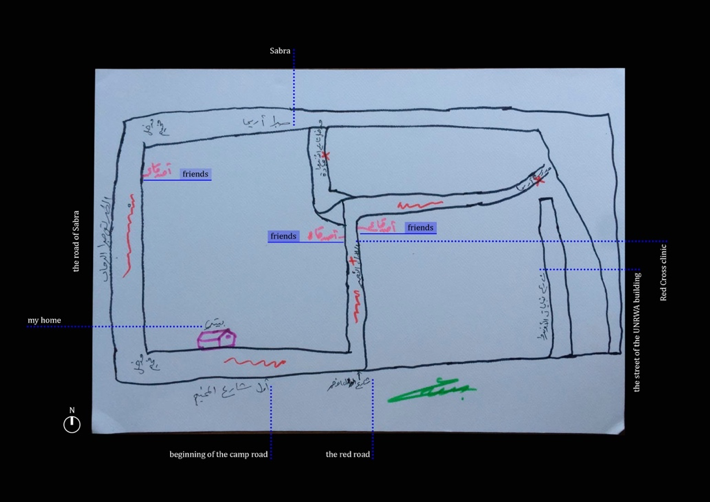

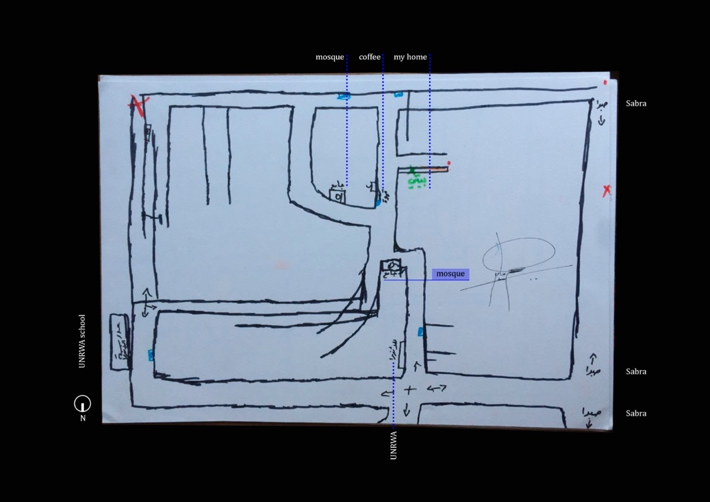

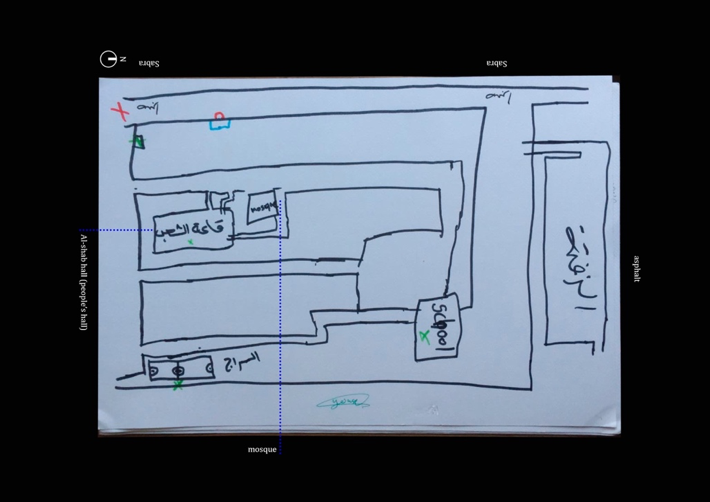

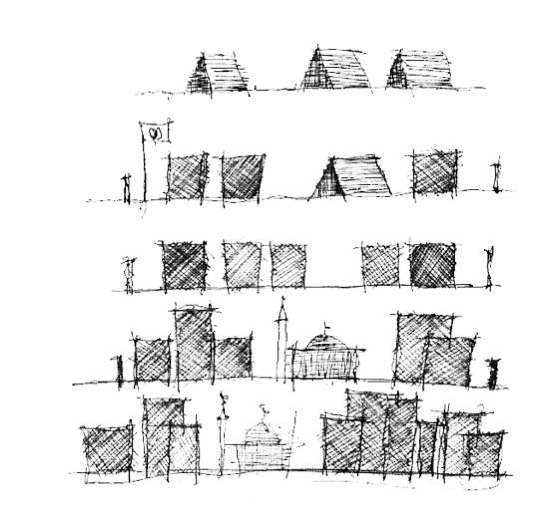

Against this backdrop, counter-mapping Shatila, and refugee camps broadly, acquires enhanced pertinency and urgency in order to destabilize externally produced narratives of camps’ humanitarian dependency, socioeconomic poverty, and unregulated makeshift urbanism. In this sense, the research design was based on the generation of multiple mapping accounts—a proto-atlas—produced by camp residents that describe Shatila from their perspective. The counter-mapping project’s research questions aimed to tackle the perceptions of Shatila as a “Palestinian refugee camp,” mobilize the multiple migration layers constituting the place, and challenge the built environment and its relations with the notion of marginalization and “gray spacing.”39 In total, five sketch mappings were drawn freehand by research collaborators at separate times: two one-to-one encounters with the researcher, in the case of Munir and Dima; and one collective mapping encounter with Sara, Ahmad, and Abed, where the interaction of the three in each other’s mapping process was very important. Understanding mapping as a platform of knowledge production was corroborated by the analysis of the transcript of the conversation that took place while mapping. Furthermore, during the month of immersive fieldwork, I conducted walk-along interviews with other camp residents as embodied mapping in Shatila and surrounding areas, “expert” interviews, participant observation, and re-elaboration of self-presence in the “campscape,” defined as a processual and elastic understanding of the urban refugee camp space. Interviews were held in English and Italian, and with the support of Munir and Abed for the translation to and from Arabic.

COUNTER-MAPPING FROM SHATILA: PRESENTATION OF THE RESULTS

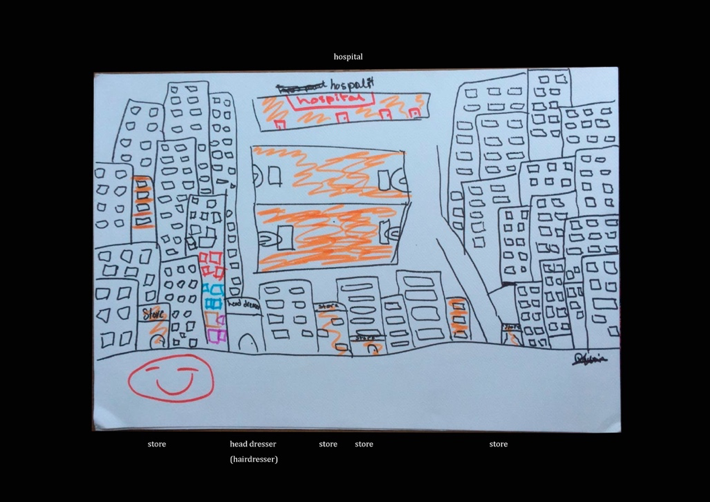

Mindful of the discussion on counter-mapping exposed in the first part of the article, the pages below follow the discursive paths traced by the sketched maps and the conversations around their making. Guided by the excerpts of conversation and suggestions quoted throughout the text, the discussion is anchored by the landmarks and features that emerged while mapping. It thus foregrounds the plurality of space perceptions stemming from the same locality and the social constructs of care that punctuate the “campscape.” Narratively, the mappings lead us through the inside and outside of Shatila, enlivened by the social life of the streets; revealing the uncommodified relations of care and social infrastructures, including the physical spaces (schools, clinics, sports clubs) where these unfold and materialize; as well as uncovering themes of homemaking, emplacement, and housing. I will refer to the research collaborators with fictional names and imprecise social positions in order to preserve their anonymity. The following images (Images 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) are the maps produced by the research collaborators Munir, Sara, Ahmad, Abed, and Dima. Except for one, the maps appear to resemble traditional imaginaries of aerial view cartographies, where the camp is represented with lines and signs to define borders and streets. They also bear a certain resemblance to the “official” map displayed in NGO offices in the camp (Image 1E), clearly marking the main roads cutting across the camp space that are absent in the digital mapping platforms representations. But especially, they are enriched by written and symbolic subjective information.

Outside/Inside

Contrasting the impressions emanating from the built environment where Shatila has achieved perfect aesthetic and material camouflage with its surrounding space,40 Images 2–5 starkly demarcate the contours of the camp, effectively drawing a caesura outside and inside which is discursively recurrent across all conversations and interviews. Munir, a Palestinian refugee, founder, and coach of a sports club for boys and girls based in the camp, told me:

I was born outside Shatila, my family’s house was 700 meters from Shatila’s border. We moved inside Shatila in 1985 for the War of the Camps, when everyone moved to the zone controlled by the party or group they belonged to. Sticking together was the only way to be protected from the violence of the conflict.

Drawn by Coach Munir, Image 2 is characterized by the seemingly random distribution of colored dots, especially in the southern part of the camp, representing the housing mix within the same building. An orange, a red, and a green dot placed close together signify that the different floors of the same building are occupied by families of different origins. For instance, in the building he marks as “home” live three Syrian families; in the next building live Syrian, Lebanese, and Palestinian families; in the following building half of the families are Syrian, half are Palestinian. Tired of pointillism, after a while he covered the rest of the map with evenly scattered colored dots, underscoring though that the distribution is not accidental.

Deeper inside the maze is also the safer from Lebanese Security incursions—that would not dare venturing so far in. Camp dwellers who have reasons to be afraid for themselves and their families’ safety (for fear of reprisals deriving from their political and militant activities back in Syria, irregular residency statuses, lack of working permits, to cite some) prefer settling in the most internal locations possible.

Thereby, they are seeking invisibility in numbers. Thus, Munir continues to explain, “Along the main streets mostly live Palestinian refugees from Lebanon: even if inside the camp, these are the most exposed locations.”

Specifically researching Shatila, Diana Martin has proposed that we speak of a “campscape” to underscore the difficulty in localizing the so-called “space of exception”41 when the refugee camp enmeshes with the urban concretely, semantically, and relationally.42 She coined the term drawing from the popular theory of global cultural flows articulated by Arjun Appadurai. Accordingly, the metaphoric reference to the liquidity of thinking through “campscapes” suggests a departure from bordered thinking that divides the object “space” in hermetic sections—exception inside the camp, citizenship outside the camp. It also foregrounds the surpassing of the static and contrasted figures of displaced refugees and urban citizens.43 Camps and their immediate surroundings merge, for they compose an irregular and unpredictable complex encompassing the lived experiences of refugees and other communities living at the “margins” of cities. In this sense, the refugee camp as a conceptual device is contested, manipulated, and perforated by the actions, practices, and claims of those it is intended to contain.44 And yet Munir’s testimony suggests that the effect of legal regimes continues to haunt camp residents’ experiences. The relevance of the camp’s official borders remains salient for those who rely on a strict distinction between camp and the rest of the city.

The legend on Munir’s map reads: Green: Palestinian; Red: Syrian; Orange: Lebanese; Pink: Bangladeshi; Purple: . . . [text is missing but he meant to represent Kurds]. What is sometimes described by residents as the “cosmopolitan character” of Shatila—where the public display of Palestinian nationalist aesthetics has been negotiated—denotes the overlapping displacements and migratory trajectories that cross and become embedded in the camp.45 The war in Syria is extensively mentioned as trigger and catalyst of the last decade’s changes in social composition of the camp—wherein, over time, Syrian nationals along with Palestinian and Kurdish minorities crossed over to Lebanon and sought shelter and livelihood in an uneven geography of urban dispersal, rural encampments, and formal Palestinian refugee camps, expecting to go back or waiting for the conditions to move elsewhere.

Yet the camp is also home to residents originally from beyond the region, as I was repeatedly reminded by research collaborators’ testimonies and interviews with two women of East Asian origin. Consider Karen, a Sri Lankan woman who followed her sister to Lebanon in 1982 when she was fifteen years old; both were on sponsorship from a Lebanese agency for domestic workers. A family hired Karen to care for the family’s elders. She worked as a nurse there for five years. During this time, she met her husband, a Palestinian from Shatila, who worked as driver for the same family. The Lebanese family they worked for provided them with a place to stay after they got married, until they did not anymore, and Karen with her husband moved to a building where people were squatting after the camp war.46 Once forced out of there too, they moved into Shatila where the husband had a home.

Exemplifying the diversity of the camp residents, I could also recount the story of Josephine, who is originally from the Philippines and arrived in Beirut in 1989. The eldest of nine children born to peasant parents, Josephine decided to migrate for work and to better the livelihoods of her family. After six years in Qatar, she moved to Lebanon through a domestic workers employment agency. Josephine married a Palestinian man who worked as a security guard for the same agency. Despite being Palestinian, he had Lebanese friends who let him work with them. After their marriage in 2014, the couple moved to Shatila because her husband had family and a house there. Four of her sisters have followed her migration path to Beirut to support their husbands and children who remain in the Philippines. Josephine also knows other Filipino women in Shatila who are married to Palestinian men. However, being married does not grant them the right to work, thereby exposing them to the risk of jail if they were to be discovered while at work. The narratives of both women developed clearly around the binary “before Shatila” and “once inside Shatila”—where, with similar tonalities, they apprehend the latter by the sense of enhanced safety they experience in the camp. Especially Josephine expressed that despite the shortcomings of living in a camp, Shatila meets her need for a sense of safety to bring up her small child, hinting at the converse existing outside the camp where she lived “before Shatila.”

Recognizing the diverse composition in terms of origin, migration history, gender, religion, and legal status of the inhabitants of Shatila exposes the sociospatial formations constitutive of the “campscape” that were recurrently voiced in the mappings and interviews. The most evident manifestation is exemplified by multiple research collaborators citing the Bangladeshi market on Sundays—a visible instance whereby the Bangladeshi community of Shatila appropriates the street space, temporarily re-signifying it culturally and economically. For the research collaborators, the streets of Shatila feature prominently in Images 2–5—the streets “large enough for one car and a scooter to get through.” Only Munir, in Image 2, draws the narrow alleys reticulating across the camp in light blue—alleys invisible from the aerial perspective as they are almost tunnels in the maze of the camp. Intuitively for the research collaborators, streets draw the line between inside/outside; but they are also embedded in performance of power and socioeconomic relations. Sara, Ahmad, and Abed—authors of Images 3, 4, and 5—debated extensively on the importance of streets as the only available public space where the display of power and control by armed and political forces of the camp collides with the banality of everyday life—street businesses, NGOs and INGOs signs, video arcades’ dimly lit rooms, coffee stands, and various clinics that they signpost in their drawings. Ahmad and Abed are two Palestinian boys I met through the sports club. They decide to punctuate Images 4 and 5 with sporadic red crossings and dots to pinpoint locations in Shatila where they would not want to stick around too long as being seen in those particular spots draws unwanted attention from those exercising invisible armed surveillance over the camp. Surveillance and control from internationally sponsored parapolitical structures materialize concretely in the public sphere of the camp.47

Migrant Infrastructures

In an article on the tangible and everyday ways resources are accessed and reconfigured by migrants and other groups cast outside the dominant national and urban registers, Suzanne Hall and her colleagues retrace the hybrid repertoire of civic resourcefulness and economic experimentation (ranging from unpaid labor, to cooperative organization, to translocal networks of remittances, and economic activities) that emerges to substitute local state resources withdrawn from welfare and social infrastructures.48 In one of his earliest works, Abdoumaliq Simone identifies “people as infrastructure” in this reticulated process.49 Through framing people as infrastructure, Simone demonstrates that fragmented migrant groups form interdependencies on one another that substitute modes of solidarity and familiar spaces they left behind or were uprooted from. The following paragraphs illustrate how Shatila’s residents resonate with this argument.

Through the sports club I met Sara, a Syrian woman who had been living in Shatila for twenty-five years at the time of my fieldwork. She vocally longs for Syria and reminisces about the life she had there, “where the government provided for its people and the land was fruitful.” Sara marks the streets in Image 3 with red to represent that everything in Shatila is a problem, including: “the bumpy roads full of holes accumulating ponds of stagnant water emanating a unique pungent smell, the exposed electricity cables that supply intermittent power and electrocute people in the camp, the under-resourced medical infrastructures.” She crosses over the UNRWA medical clinics to point out that they are overwhelmed by the number of patients who need treatment and can only provide basic medical assistance due to lack of equipment. Although her pessimism was intermittently broken by laughter as Abed and Ahmad ironized Shatila’s contradictions, Sara’s subjectivity as caretaker for many in her family comes across through her focus on Shatila’s inadequate medical infrastructure. The repercussions deriving from poor healthcare directly affect the health of the residents. As Coach Munir bluntly put it, “How is this possible! UNRWA is given a budget to provide for Palestinian refugees, but if they do not even provide basic health, what should they provide?” Walking out of Shatila from its northern entry point, he also pointed at the “fridge for dead people,” specifying that “it was donated by some NGO because to keep the dead in a Lebanese hospital you have to pay.” Initiatives have also been developed to supplement the deficient “official” medical infrastructures. For example, Beit Atfal Assumoud, a Palestinian NGO present in many Palestinian camps in Lebanon,50 opened a doctor’s practice in Shatila to expand the healthcare offered to the beneficiaries of the NGO’s programs. Similarly, soon after the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, the association Basket Beats Borders established a medicine distribution point to supply essential drugs to families of the camp that cannot afford or find them. In fact, since the Lebanese economy’s crash, even imports of medical equipment have dropped catastrophically.51

However, the relevance of national identity as exclusivist or prioritizing criteria among refugee humanitarian providers reverberates through some of their stories. In our interview, Karen’s daughter Zeina recounts that she has had hearing problems since she was a girl, which slowed her down in finishing school. She attended remedial classes in the Palestinian NGO Beit Atfal Assumoud in Shatila during her childhood and teenager years. Years later, Zeina needed economic support and the same NGO proposed for her to join the NGO, this time as a nursery teacher. As Zeina pointed out that her mother is Sri Lankan, the NGO worker replied, “No problem, we do social work, we don’t care what is in your paper. And anyway, your father is Palestinian.” At the time, the NGO could also help her with her mother’s (Karen) visa, which was too expensive for either the mother or daughter to afford. Bait Atfal Assumoud took them under their wing as a “hardship” case, thus taking responsibility for covering the visa renewal. The financial sustainability of Karen’s case specifically was eased by the fact that on top of the extreme family condition and the Palestinian husband, Karen had also lived in Malaysia and at the time the NGO was receiving support from Malaysian Muslim donors. Curiously, during an encounter with other social workers from the same NGO and with Children Youth Centre’s Abu Nabil, some clues were given that beneficiaries of the NGOs with Palestinian identity or related to someone Palestinian were prioritized, even though the NGOs publicly present their programs as offering gratuitous care for “all the people of Shatila.”

Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh’s work in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon is a powerful reminder that at regulatory, aid provision, and epistemological levels spaces of asylum are often overlooked as sites of overlapping of several communities of displaced people, some of whom have gone through multiple cycles of displacement. Recognizing these facets is fundamental to understanding that internal hierarchies in camps preclude equal access to spaces, services, and resources : “Having been there longer” produces the power to delimit the space and resources offered to newcomers.52 Additionally, the temporal extension of the displacement of “newcomers” that parallels the weathering of shared personal and collective resources progressively deteriorates the relations between camp groups as material conditions reinforce social fragmentation. Oren Yiftachel captures this occurrence with the notion of defensive urban citizenship53—meaning that groups exposed to the price of space deterioration gradually erect a shield of defensiveness in the attempt to fend off newcomers to their localities and resources. Although the research collaborators did not elaborate on this explicitly in the mappings, it seems to be reflected in the correlation between the national identity of the map’s author and the places of care provision included (and excluded) in their map.

Abed and Ahmad represented the UNRWA school they went to at the northeastern corner of Shatila, just outside the intricate street fabric of the inner camp. Palestinian refugee children and teenagers complete their whole education career here, as schooling falls within the UNRWA’s responsibilities. Other non-Lebanese children instead are guaranteed the right to education by the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, which mandates the Lebanese State to grant such rights, and the UNHCR has committed to cover the tuition fees for Syrian children to overcome barriers of affordability.54 According to Reem, a young Palestinian woman who works as journalist for Campji,55 schooling conveys contrasts between Palestinian and Syrian Shatila residents. She says, “From the Palestinians’ point of view, Syrian children have plenty of choice. They can choose between going to Lebanese public schools as ‘second shifts’ in the afternoon”—that is to segregate Lebanese kids from Syrians for fear the latter would affect the learning of the former.56 “Or they can go to UNHCR schools—that is to say the Non-Formal Education programs. On the other hand, Palestinian children from long-time Shatila resident families can only go to the UNRWA school, which has been accommodating an additional number of students by also including Palestinian refugee children displaced from Syria.”

To further complicate the context, people displaced from Syria, and especially Palestinian Syrians, suffer quotidian experiences of harassment and violence on the streets—as extensively testified by NGO workers in the interviews. Huda, a young woman who works as translator for Humanitarian Corridors in various locations in Lebanon, told me:

They don’t feel safe. They are insulted and they are beaten up when they walk in the streets. A family we followed that eventually managed to leave to Italy was constituted by a mother with two daughters; the mother used to let the girls go before her in the streets and in shops, until she saw that both kids and adults were bullying and harassing the girls because they were Syrian. After that moment she never let them out of the home again, not even to go to school.

Daniel and Carl are two European university graduates who volunteer for the NGO 26 Letters, which works on the assumption that students displaced from Syria stop attending school because their parents keep them home, as they fear that the children could be beaten on their way to and from school. They spoke in length about what they witnessed in their experiences:

Some parents also fear reprisals for their own pasts from other Syrian men in the camp, who allegedly kidnap the kids on their way to or from school and sell them back to Syria. We as 26 Letters reach these Syrian (including Palestinian from Syria) families directly in their homes, to give out the regular school syllabus in a place the families feel safe.

While on the one hand the case further exemplifies Shatila’s social fragmentation, on the other hand it illustrates the preparedness of the camp’s resources to activate in different modalities and cope with the challenges posed by the “campscape.” The migrant infrastructure as formulated by Hall and colleagues is coproduced by the perceived and/or funded absence of security in the streets of Shatila, the vulnerable position of some of its residents, and the willingness to nonetheless school the children in homes that temporarily function as formal educational spaces.57 It is articulated by the residents themselves who activate a variety of resources to link diversified social compositions with individual capacities and needs, thereby achieving the maximum outcome from minimal resources. In this sense, counter-mapping serves as a catalyzing process for surfacing the migrant infrastructure and ramifications that fill the “grey blob” of Shatila’s official representations in widely accessible digital mapping platforms; it simultaneously registers and fixes these complexities as archive for future rights claim, should the need arise.

A Special Spatial Opening

The football field features in three maps: the one made by Coach Munir, who spends most of his days there; Image 5 drawn by Abed, who regularly trains and plays there; and Image 6 drawn by Dima, a young Palestinian woman, university student, and basketball player. The field lies at the southeastern corner of the camp, standing in stark contrast with the rest of the camp’s cramped architecture. This tiny plot of land is nestled among residential buildings that overlook its green synthetic grass and four goals, allowing the eyes to breathe (Image 7). For Dima, “the field is important because sports are a cure, an alternative, a possibility, other than drugs for the boys and young men of Shatila—Syrian, Lebanese, and Palestinian alike.” According to Reem,

Campji itself is constituted by a mix of young people from the camp—attesting to the fact that young people are not so much influenced by resentment generated by past histories, as opposed to the older generations that have lived the traumas of exile, war, and camp conflicts. The young camp inhabitants build relationships with each other based on shared interests, overcoming the initial diffidence stemming from diversity and othering.

Thus, they come to appreciate instead the potential and creativity generated by coexistence, cohabitation, mutual comprehension, and solidarity in Shatila.

According to Dima, “The playfulness of practicing sports together stirs away that diffidence and constructs social and friendship bonds that bring together boys and girls from Shatila of all national identities—Palestinian, Lebanese, Syrian, Sudanese” in a metaphorical space of education where personal problems are temporarily suspended by fun. Basket Beats Borders and Palestine Youth FC—like other sport and youth initiatives in the camp—offer this space to girls and boys of Shatila, where they can enjoy sports, irrespective of where their papers say they are from. Also, “they are encouraged through sport to take a hard look at socially relevant issues, as sport teaches to resolve differences peacefully, develop the ability to deal with defeat, and form personalities,” says Coach Munir. Although left unexplored by this research, documentary films like Footballization and Sisterhood attest to the role sports play in bridging social divides in refugee camps in Lebanon—challenging the notion of the camp as a purely humanitarian space, or an overdetermined political space.58 And they do so via the audiovisual form’s potential to reach and affect wider audiences than academic articles can wish to attain.

To some extent a recognized social leader in Shatila, Coach Munir has been receiving the visits of many Syrian and Palestinian from Syria families living in the camp. In his own words,

They come to me to ask for help because now there is a better relationship. The representative of the Palestinians from Syria in the camp came to speak with me. Palestinians from Syria are more in need of jobs, while Syrians usually come to ask for aid and advice on how to get access to aid services and support. I believe that being active in the civic society as I try to be all the time with the people of Shatila—but being open to help also others—attracts people since they see you are a good person.

Again, it is curious that a self-reliant sports club with modest resources acts as a social services provider in a landscape teeming with INGOs with generous budgets. The social infrastructure it embeds and produces entails not only the exchange of advice and a friendly ear but also a point of medicine distribution and a food bank for the neediest families of the camp as the capacity of the club to provide momentarily increased—and while the demand is in constant increase and never met. Counter-mapping from the football field—the sports clubs more widely—is counter-narrating: that even in conditions of very limited resources, and despite national, political, ethical differences, refugees and camp residents set in place mutual support strategies that are hard to overrate.59

Homes and Houses

Lastly, one notices the striking representation of the houses of Shatila by Dima, in Image 6. She chose to use the black pen because generally things in Shatila are bad, thus black contours seemed appropriate to her. With no hesitation, she started drawing one rectangle and filling it with little squares. Then started drawing the next rectangle, and filling that too with small squares. I quickly realized she was representing the tall buildings of Shatila and their windows. Halfway across the paper, she stopped drawing buildings to draw the football field and playground. To conclude, she colored a few buildings in orange that represent special places such as her friends’ houses, and one in multicolor which is the house where she lives with her father and grandmother. “They used to live not far from the camp, in Tariq el-Jdideh neighborhood; however, due to the worsened economic conditions of the family they had to move into Shatila four years ago,” she reveals with sadness. Emotionally and materially dealing with the worsening of personal housing conditions also characterizes the testimonies that Huda, the Humanitarian Corridors worker, hears every day.

Recountings from Yarmuk Camp in Damascus—where a lot of Palestinians from Syria are from—describe a normal neighborhood whose only exceptionality was the (invisible) legal ascription of camp status. Many of them who now live in Palestinian camps in Lebanon are extremely disconcerted by their new living situations: houses are dark, damp, rarely receive direct sunlight, and are precariously cramped one upon the other.

The alternative perspective is that since the war in Syria has forced unprecedented large numbers of people to seek cheap and not necessarily permanent housing solutions in Lebanon, the housing market in Shatila has rapidly evolved. Syrians are “renting out from Palestinians who had evicted other Palestinians to rent to Syrians since Syrians supposedly could be charged higher prices as they receive food vouchers and pocket money from INGOs.”60 An existing camp housing market emerges, where Palestinian refugee homeowners in Shatila rent their dwellings as a means of income—whereby owners are intended refugees who registered owning a house with the camp committee. In fact, as a result of the recent history of Lebanon and an inappropriately responsive housing sector, the pool of population in need of cheap housing has been a constant over the last thirty years—Lebanese internally displaced, seasonal laborers from Egypt and Syria, subcontinental Asian migrants, just to mention few.61 Camps were the only geographies these communities could afford, and where the indeterminacy of the gray spacing at work granted people without the legal permits to go undetected by the authorities. At an average of one extra floor built on top of existing houses every five years, construction continued, inevitably vertically (Image 8).62 Subsequently, relying on pre-existent social networks and familiarity with the camp constructed through previous seasonal labor migrations, people displaced from Syria by the war activated existent social capital to piece together shelter security in Palestinian refugee camps. Thus, the demand for rooms and flats in the camps spiked, housing expansion continued, and rent prices adjusted accordingly.63 While Palestinian flat owners harnessed an economic opportunity, Palestinian tenants suffered rent increase and at times evictions. Everyone capitalizes on the opportunities at hand, and whilst some gain benefits—securing additional income or a home—others bear the negative effects.

The emergence of a housing sector flexible and accommodating to the increased demand on the one hand, and the possibility of raising revenue from renting on the other, points to the appropriation of “formal” means for self-determination by Shatila’s residents. Shatila and its residents demonstrate that within the power geometries of contemporary urbanity and official structures, gray spaces are opened by marginalized groups which propose lifestyles that defeat detection by planning and immigration regimes through harnessing the instability of these groups’ “informality” and the retreat of state presence.64 All five mappings also reveal that houses are not just the security of a shelter: homes are the landmark everything else emanates from, graphically as well as narratively. Labeled explicitly in Images 2, 3, and 4, the home is marked by a green cross in a black box in Image 5, and, as mentioned, it is illustrated as the multicolored building in Image 6. For Sara, it is clear, “her home is the only place in all Shatila where she feels well,” while for Ahmad and Abed it is “where they can rest.” Dima evokes a performative consciousness when she describes it as “the only place where she can pull down the stiffness with which she carries herself out in the streets, where she adjusts her body language to disincentivize everyone from bothering her.” Sara and Dima also signpost—one labeling in pink, the other coloring in buildings—the houses of friends in Shatila, where positive memories rest protected and the atmosphere is merry. While marking them down, Sara was keen on explaining the sort of comfort and fun each of her friends may offer to a guest: “Playing cards, eating fruits and nuts, sweets, drinking tea and/or coffee, cigarettes, or narghile.” Friends’ homes are not only labels on maps and architectural constructs that screen intimacy and domesticity from unwanted gazes, but they are also where Sara and Dima seek support if needed—reminding us that the social infrastructure of care and support in contexts of exile, displacement, and emplacement mostly reticulates within the refugee and migrant community itself.65

CONCLUSION

The significance for individual subjectivities of a selective set of places, entrenched with emotional boundedness, that take on enough personal relevance to stand out in visual representations of Shatila calls into question how refugees and displaced people appreciate and engage with the “campscape.” I have not entered the contradictory condition that Shatila’s refugee and displaced residents—in permanent temporal exile and statelessness, yet animated by desires to return to homelands, to move to other countries, or settle under conditionality of improving material and legal conditions—manifest through an ambiguous architecture of the houses/homes.55 This ambiguity occupies the space of tension between emplacement and claims of temporariness through a system of state and camp actors’ discourses and architectural “improvements” that guarantee a quasi-urban living for the time being. A common, almost obvious (for the research collaborators) justification for the construction and development of urban forms like concrete houses in a refugee camp was that “we will leave them [the houses] to the Lebanese when we leave.”66 The prominence of homemaking in refugees’ experiences is intrinsically problematic as it brings together the experience of forced rupture from one’s home; the movement to somewhere supposedly temporary to which displaced individuals do not aspire to develop place-attachment; and yet, as temporary as it is, dwelling necessarily involves an effort in becoming-at-home for the time being.67

However, the testimonies from the mapping process unveil a plurality of stratifying thickness of Shatila that surpasses the centrality homemaking signifies in displaced and exiled experiences. Examining the first glimpses of the “campscape’s” proliferous activity through the understanding of migrant infrastructures’ formation enhances the visibility of the complexities that interlace different camp groups through the establishment of economic relations, social care, and civic responsibility. The resulting picture describes and attests to gray spaces at the margins of the official city where, to the denial of national citizenship, refugee and migrant communities have responded by reproducing life nonetheless—appropriating urban life and urbanity forms and animating them through their own formulations in a process Simone calls the “surrounds.”68 A quote from Edward Said, referring to Palestinian spaces but that can be appropriately applied to considering refugees’ spaces, gently expresses these undetected manifestations:

Whenever I look at what goes on in the interior [of Palestinian spaces] I am always surprised at how things seem to be managed normally, as if I had been expecting signs of how different “they,” the people of the interior, are, and then find that they still do familiar thing . . . that there are still chores to be done, children to be raised, houses to be lived in, despite our anomalous circumstances.69

As discussed, capturing a place through crystallized graphic visualizations such as (classic) cartographies would not be representative of the tangible and metaphysical reality pertaining to the people who inhabit the place—as much as it serves instead the purposes of those who have produced the map. Counter-mapping not only reveals the enforcement of specific territorializations but also responds to special agendas where forms of spatial planning, border setting, and territorial representation are deployed for the privatization of commons, the obscuring of communities, and the homogenization under a coherent logic of that space. Counter-mapping Shatila discloses the social, economic, personal, and symbolic relations and interdependencies between people and communities that hegemonic discourses categorize as distinct and push to the margins—refugees, urban poor, and illegalized migrants alike. These form complex social infrastructures of care and provision and economic systems that defeat the state withdrawal of resources from such communities by harnessing the porosity of “formal” systems and reproducing them outside the realm of official accounts—that is, of urbanity and citizenship. Seeing through counter-mapping fosters comprehending urban citizenship as it emerges from the critical recognition that life at the fringes of the formal city has developed far beyond strategic survival and invisibility—in Beirut, as much as in innumerable other places worldwide. This “mapping back” is not so much a response to policy makers and urban planners, but rather a stimulation for scholarly practitioners to rethink a supposed dependency of marginalized groups on the very structures that marginalize them.

NOTES

Adam Ramadan, “Spatialising the Refugee Camp,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38, no. 1 (2013): 65–77.↩︎

Rosemary Sayigh, “The Struggle for Survival: The Economic Conditions of Palestinian Camp Residents in Lebanon,” Journal of Palestine Studies 7, no. 2 (1978): 57–93.↩︎

Julie Peteet, Landscape of Hope and Despair: Palestinian Refugee Camps (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005).↩︎

Francesca Ceola, “Hospitality Relations and Overlapping Displacements in Refugee Camp(scapes) in Lebanon” (master’s thesis, Human Geography, University of Lisbon, 2021).↩︎

Denis Wood and John Fels, The Power of Maps (New York: Guilford Press, 1992).↩︎

Sofia Avila, Yannick Deniau, Alevgul H. Sorman, and James McCarthy, “(Counter)Mapping Renewables: Space, Justice, and Politics of Wind and Solar Power in Mexico,” EPE: Nature and Space 5, no. 3 (2021): 1056–85; Tania Murray Li, “What is Land? Assembling a Resource for Global Investment,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39, no. 4 (2014): 589–602.↩︎

Claudia Martinez Mansell, “A Change of Perspective: Aerial Photography and the Right to the City in a Palestinian Refugee Camp,” in Visual Imagery and Human Rights Practice, eds. Sandra Ristovska and Monroe Price (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 213–28. Based on Jess Bier’s discussion on the legacy of British cartography in present day West Bank, Martinez argues that “the blank areas on maps can become self-perpetuating”: Palestinians were first prevented from filling in the spaces that the cartographer would see as “blank,” and then they were “told that the unmapped areas can be seized precisely because they are blank” (215).↩︎

Peteet, Landscape of Hope and Despair.↩︎

Although exact numbers are not available, initially there were around 500 residential units that have since multiplied at least tenfold, through vertical construction. “Shatila Camp,” UNRWA, accessed 12 May 2023, https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/lebanon/shatila-camp.↩︎

Mona Fawaz, Ahmad Gharbieh, Mona Harb, and Dounia Salamé, eds., Refugees as City-Makers (Beirut: American University of Beirut, 2018).↩︎

Mona Fawaz, Nizar Saghiyeh, and Karim Nammour, “Housing, Land and Property Issues in Lebanon: Implications of the Syrian Refugee Crisis,” UN Habitat and UNHCR, Lebanon, accessed 15 June 2022, https://unhabitat.org/housing-land-and-property-issues-in-lebanon-implications-of-the-syrian-refugee-crisis; Romola Sanyal, “Urbanizing Refuge: Interrogating Spaces of Displacement,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38, no. 2 (2014): 558–72.↩︎

Nasr Chamma and Hassan Zaiter, “Syrian Refugees in Palestinian Refugee Camps and Informal Settlements in Beirut, Lebanon,” in Towards Urban Resilience – Proceedings –International Workshop – Barcelona 2017, eds. Annette Rudolph-Cleff, Carmen Mendoza Arroyo, and Bjoern Hekmati (Darmstadt: tuprints, 2017), http://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/id/eprint/6986; Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, “Refugee-Refugee Relations in Contexts of Overlapping Displacement,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, special issue, Spotlight On Series: The Urban Refugee “Crisis”: Reflections on Cities, Citizenship, and the Displaced (2016); Nasser Yassin, Nora Stel, and Rima Rassi, “Organized Chaos: Informal Institution Building among Palestinian Refugees in the Maashouk Gathering in South Lebanon,” Journal of Refugee Studies 29, no. 3 (2016): 341–62.↩︎

Mayssoun Sukarieh and Stuart Tannock, “On the Problem of Over-Researched Communities: The Case of the Shatila Palestinian Refugee Camp in Lebanon,” Sociology 47, no. 3 (2013): 494–508.↩︎

Marianne Hirsch, “The Generation of Postmemory,” Poetics Today 29, no. 1 (2008): 103–28.↩︎

Michele Lancione and Ash Amin, eds., Grammars of the Urban Ground, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022); Michele Lancione, ed., Rethinking Life at the Margins: The Assemblage of Contexts, Subjects, and Politics (London: Routledge, 2016).↩︎

Claudia Martinez Mansell, Mustapha Dakhloul, and Firas Ismail, “A View from Above: Balloon Mapping Bourj Al Shamali,” in This is Not an Atlas: A Global Collection of Counter-Cartographies, ed. Kollektiv Orangotango+ (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2018), 54–59.↩︎

Claudia Martinez Mansell, “Camp Code,” Places Journal, accessed 20 June 2022, https://placesjournal.org/article/camp-code/?cn-reloaded=1#ref_11.↩︎

Arteeast, “Interview with Ismael Sheikh Hassan,” accessed 15 May 2023, http://arteeast.org/quarterly/interview-with-ismael-sheikh-hassan/.↩︎

Ismael Sheikh Hassan, “Activism in the Context of Reconstructing Nahr al-Bared Refugee Camp: Lessons for Syria’s Reconstruction?,” Arab Reform Initiative, accessed 15 May 2023, https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/activism-in-the-context-of-reconstructing-nahr-al-bared-refugee-camp-lessons-for-syrias-reconstruction/.↩︎

Ayham Dalal, From Shelters to Dwellings: The Zaatari Refugee Camp (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2022).↩︎

Alessandro Petti, “Refugee Heritage (2015–2021), Introduction,” Decolonizing Architecture Art Research, accessed 15 May 2023, https://www.decolonizing.ps/site/introduction-4/.↩︎

Wood and Fels, The Power of Maps.↩︎

Nour Joudah, “Topography of Gaza: Contouring Indigenous Urbanism,” Jadaliyya, 15 May 2023, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/45043.↩︎

Gillian Rose, “Looking at Landscape: The Uneasy Pleasure of Power,” in The Cultural Geography Reader, eds. Timothy Oakes and Patricia L. Price (London: Routledge, 1993); Denis Cosgrove, “Geography is Everywhere: Culture and Symbolism in Human Landscapes,” in Horizons in Human Geography, eds. Derek Gregory and Rex Walford (London: Red Globe Press, 1989); Cosgrove, “Prospect, Perspective, and the Evolution of the Landscape Idea,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 10, no. 1 (1985): 45–62.↩︎

Neil Smith, “Geography, Empire, and Social Theory,” Progress in Human Geography 18, no. 4 (1994): 491–500.↩︎

Bruno Latour, “Centers of Calculation,” in Science in Action, How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987), 215–57.↩︎

Matthew H. Edney, Mapping an Empire: The Geographical Construction of British India, 1765–1843 (London: University of Chicago Press, 1997).↩︎

John Brian Harley, “Silences and Secrecy: The Hidden Agenda of Cartography in Early Modern Europe,” Imago Mundi: The International Journal for the History of Cartography 40, no. 1 (1988): 57–76; John Brian Harley, “Deconstructing the Map,” Cartographica 26, no. 2 (1989): 1–20.↩︎

Alfredo Wagner Berno de Almeida, Sheilla Borges Dourado, and Carolina Bertolini, “A New Social Cartography: Defending Traditional Territories by Mapping in the Amazon,” in Kollektiv Orangotango+, This is Not an Atlas, 46–53.↩︎

Wood, Power of Maps; Cosgrove, “Prospect, Perspective.”↩︎

Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1960); Leila M. Harris and Helen D. Hanzen, “Power of Maps: (Counter)Mapping for Conservation,” ACME An International Journal for Critical Geographies 4, no. 1 (2006): 99–130.↩︎

Harris and Hazen, “Power of Maps,” 106; André Mesquita, “Counter-Cartographies: Politics, Art and the Insurrection of Maps,” in Kollektiv Orangotango+, This is Not an Atlas, 26–35.↩︎

Nancy L. Peluso, “Whose Woods are These? Counter-Mapping Forest Territories in Kalimantan, Indonesia,” Antipode 27, no. 4 (1995): 383–406.↩︎

Christian Reichel and Urte Undine Frömming, “Participatory Mapping of Local Disaster Risk Reduction Knowledge: An Example from Switzerland,” International Journal of Disaster and Risk Science 5 (2014): 41–54; Julia Risler and Pablo Ares, “X-Ray of Soy Agribusiness in the Pampa and Mega-Mining in the Andes,” in Kollektiv Orangotango+, This is Not an Atlas, 86–91; Wagner Berno de Almeida et al., “A New Social Cartography.”↩︎

Nell Gambiam, “Mapping Palestinian Identity in the Diaspora: Affective Attachments and Political Spaces,” The South Atlantic Quarterly 117, no. 1 (2018): 65–90; Rebecca Solnit, Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2010); Severin Halder and Boris Michel, “Editorial – This is Not an Atlas,” in Kollektiv Orangotango+, This is Not an Atlas, 12–25.↩︎

Jamie Scott Baxter, Séverine Marguin, Sophie Mélix, Martin Schinagl, Ajit Singh, and Vivien Sommer, “Hybrid Mapping Methodology: A Manifesto” (SFB 1265 Working Paper Series No. 9, Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin, 2021), https://doi.org/10.14279/depositonce-18197, 7; Sybille Krämer, Medium, Bote, Übertragung. Kleine Metaphysik der Medialität (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 2008); Sybille Krämer, “‘Kartographischer Impuls’ und ‘operative Bildlichkeit’: Eine Reflexion über Karten und die Bedeutung räumlicher Orientierung beim Erkennen,” Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaft 12, no. 1 (2018): 19–32, https://doi.org/10.14361/zfk-2018-120105.↩︎

Martina Tazzioli and Glenda Garelli, “Counter-Mapping, Refugees and Asylum Borders,” in Handbook of Critical Geographies of migration, eds. Katharyne Mitchell, Reece Jones, and Jennifer L. Fluri (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019).↩︎

Solnit, Infinite City.↩︎

Oren Yiftachel, “Epilogue: From ‘Gray Space’ to Equal ‘Metrozenship’? Reflections on Urban Citizenship,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39, no. 4 (2014): 726–37.↩︎

Diana Martin, “From Spaces of Exception to ‘Campscapes’: Palestinian Refugee Camps and Informal Settlements in Beirut,” Political Geography 44 (2014): 9–18; Lucas Oesch, “An Improvised Dispositif: Invisible Urban Planning in the Refugee Camp,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 44, no. 2 (2020): 349–65.↩︎

Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998).↩︎

Martin, “From Spaces of Exception.”↩︎

Arjun Appadurai, “Putting Hierarchy in its Place,” Cultural Anthropology 3, no. 1 (1988): 33.↩︎

Martin, “From Spaces of Exception”; Lucas Oesch, “An Improvised Dispositif.” See also Michel Agier, “Between War and City: Towards an Urban Anthropology of Refugee Camps,” trans. Richard Nice and Loïc Wacquant, Ethnography 3, no. 3 (2002): 317–41; Romola Sanyal, “A No-Camp Policy: Interrogating Informal Settlements in Lebanon,” Geoforum 84 (2017): 117–25; Anna Marie Steigemann and Philipp Misselwitz, “Architectures of Asylum: Making Home in a State of Permanent Temporariness,” Current Sociology 68, no. 5 (2020): 628–50; Peter Grbac, “Civitas, Polis, and Urbs: Reimagining the Refugee Camp as the City,” Refugee Studies Centre, Working Paper Series 96 (2013): 1–35; Mona Fawaz, “Planning and the Refugee Crisis: Informality as a Framework of Analysis and Reflection,” Planning Theory 16, no. 1 (2017): 99–115; Diana Martin, Irit Katz, and Claudio Minca, “Rethinking the Camp: On Spatial Technologies of Power and Resistance,” Progress in Human Geography 44, no. 4 (2020): 743–68.↩︎

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, “Refugee-Refugee Relations.”↩︎

For makeshift housing in unused palaces and hotels during the war, see Gregory Buchakjian, “Spaces Regained: Unstable Homes and Multiple Uses,” chap. 4 in Abandoned Dwellings: A History of Beirut, eds. Gregory Buchakjian and Valérie Cachard (Beirut: Kaph Books, 2018).↩︎

Peteet, Landscape of Hope and Despair.↩︎

Suzanne Hall, Julia King, and Robin Finlay, “Migrant Infrastructure: Transaction Economies in Birmingham and Leicester, UK,” Urban Studies 54, no. 6 (2017): 1311–27.↩︎

Abdoumaliq Simone, “People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg,” Public Culture 16, no. 3 (2004): 407–29.↩︎

As NGO, Beit Atfal Assumoud runs complementary school projects, women empowerment courses, and supporting families in extreme difficulty, accessed 28 June 2023, https://www.socialcare.org/portal/home/1.↩︎

Personal communication with Munir, 7 December 2020.↩︎

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, “Refugee-Refugee Relations.”↩︎

Yiftachel, “Epilogue.”↩︎

Maurice Crul, Frans Lelie, Özge Biner, Nihad Bunar, Elif Keskiner, Ifigenia Kokkali, Jens Schneider, and Maha Shuayb, “How the Different Policies and School Systems Affect the Inclusion of Syrian Refugee Children in Sweden, Germany, Greece, Lebanon and Turkey,” Comparative Migration Studies 7, no. 10 (2019): 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-018-0110-6.↩︎

Campji is a Shatila-based media production platform, http://campji.com.↩︎

Crul et al., “How the Different Policies”.↩︎

Hall et al., “Migrant Infrastructure.”↩︎

Footballization, directed by Francesco Furiassi and Francesco Agostini

(Italy, Lebanon, 2019), https://mubi.com/films/footballization; Sisterhood, directed by Domiziana De Fulvio (Italy, 2020), https://sisterhood.film/en.↩︎

Milton Santos, “O retorno do território,” OSAL: Observatorio Social de América Latina 6, no. 16 (2005): 255–61; Darling, “Forced Migration and the City.”↩︎

Abu Nabil, interview by Francesca Ceola, Shatila refugee camp, 18 February 2020.↩︎

Martin, “From Spaces of Exception.”↩︎

Chamma and Zaiter, “Syrian Refugees in Palestinian Refugee Camps.”↩︎

Sanyal, “A No-Camp Policy.”↩︎

César Giraldo, Economía popular desde abajo (Bogotá: Ediciones desde abajo, 2017); Christian Schmid, Ozan Karaman, Naomi C Hanakata, Pascal Kallenberger, Anne Kockelkorn, Lindsey Sawyer, Monika Streule, and Kit Ping Wong, “Towards a New Vocabulary of Urbanisation Processes: A Comparative Approach,” Urban Studies, 55, no. 1 (2018): 19–52.↩︎

Ahmed Alaqra, “Temporality and Time Rupture: Architecture and Urbanism of Uncertainty in Palestinian Refugee Camps” (master’s thesis, Urban Strategies and Design, University of Edinburgh, 2015).↩︎

Caroline Lenette, “Women as Hybrid Hosts: Challenging the Myth of Host Communities,” Refugee Hosts, 20 June 2022, https://refugeehosts.org/2022/06/20/women-as-hybrid-hosts-challenging-the-myth-of-host-communities.↩︎

Ghassan Hage, “A Not So Multi-Sited Ethnography of a Not So Imagined Community,” Anthropological Theory 5, no. 4 (2005): 463–75; Annika Lems, “Placing Displacement: Place-Making in a World of Movement,” Ethnos 81, no. 2 (2016): 315–37.↩︎

Abdoumaliq Simone, The Surrounds: Urban Life within and Beyond Capture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022).↩︎

Edward Said, After the Last Sky, Palestinian Lives (London: Vintage, 1987), 67.↩︎