Chloë Emmott

“NO WONDER THAT ON THIS SPOT GOD SPOKE TO US”: THE INTERSECTION OF ANGLICAN TOURIST-PILGRIMS AND ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITISH MANDATE PALESTINE

Abstract

For British Anglican tourists, archaeological tourism in Palestine marked an expansion of a broader British cultural and religious relationship to Palestine as a land made familiar by a childhood of bible stories and nativity scenes, and one which played a role in the biblification of Palestine and the appropriation of its past to validate and strengthen a connection to Britain and the Mandate. Archaeology offered a direct link to the materiality of the biblical past, experienced via a “kairotic moment” in which the past meets the present. By examining reports of British travelers to Palestine, this article considers how materially embodied religious experiences not only drove tourist movement to Palestine but also functioned as a keystone in Britain’s relationship with Palestine during the Mandate period. Behind this growth in archeological tourism, however, is a story of tension, most notably between Mandate Palestine’s first director of antiquities, John Garstang, and the Mandate and Westminster governments. From his optimism in a report on the future of archaeology in Palestine in 1919 to his bitter resignation in 1926, Garstang’s story represents the Mandate’s failures with regard to archaeology. These tensions and Garstang’s unease foreshadowed the development of archaeology as a tool of settler colonialism in occupied Palestine today.

خلاصة

بالنسبة للسياح البريطانيين التابعين للكنيسة الأنغليكانية، كانت السياحة الأثرية في فلسطين بمثابة توسع لعلاقة ثقافية ودينية بريطانية أوسع مع فلسطين كأرض عرفوها من خلال طفولة أمضيت مع قصص الكتاب المقدس ومشاهد المهد. ومن ناحية أخرى لعبت هذه السياحة دورًا في تحويل فلسطين إلى أرض الإنجيل والاستيلاء على ماضيها لإثبات وتقوية العلاقة مع بريطانيا والانتداب. كما قدم علم الآثار رابطًا مباشرًا إلى مادية الماضي المسرود في الإنجيل، يعاش من خلال "اللحظة المناسبة" حيث يلتقي الماضي بالحاضر. من خلال قراءة تقارير المسافرين البريطانيين إلى فلسطين، تتناول هذه المقالة كيف أن التجارب الدينية المتجسدة ماديًا لم تدفع فقط حركة السياحة إلى فلسطين، بل عملت أيضًا كحجر أساسي في علاقة بريطانيا بفلسطين خلال فترة الانتداب. لكن وراء هذا النمو في السياحة الأثرية هناك قصة توتر، ولا سيما بين أول مدير للآثار في فلسطين الانتدابية ،جون جارستانج، وحكومة الانتداب والحكومة البريطانية. من تفاؤله في تقرير عن مستقبل علم الآثار في فلسطين في عام 1919 إلى استقالته المريرة في عام 1926، تمثل قصة جارستانج إخفاقات الانتداب فيما يتعلق بعلم الآثار. تنبأت هذه التوترات وقلق جارستانغ بتطور علم الآثار كأداة للاستعمار الاستيطاني في فلسطين المحتلة اليوم.

INTRODUCTION

The 1920s saw an expansion of British tourism to Palestine which coincided with the start of what some archaeologists consider the “Golden Age” of biblical archaeology.1 During the Mandate era, tourism in Palestine increased; documents examined by Kobi Cohen-Hattab suggest that there was an average of 80,000 visitors per annum between 1926 and 1945, thousands more than in the Ottoman era.2 Not all these tourists were British or Anglican; there was a considerable development of Zionist tourism3 and continuation of the traditions of Christian and Muslim pilgrimage. However, as British tourists visiting during the early days of the British Mandate, these tourists represent a specific category of tourists who merit investigation, due to their relationship with Palestine as the Holy Land and as a British imperial possession, gained as a result of war. Unlike other areas popular with archaeological tourists in the Middle East, such as Egypt and Syria, Palestine lacked spectacular ruins or sensational headline-grabbing finds such as the tomb of Tutankhamun. However, Palestine offered what other areas could not: the Holy Land, a land with which many Britons, particularly Anglican Christians, felt a deep affinity due to their culture’s well-established reverence for Palestine. This connection, which deepened in the nineteenth century, has been considered by scholars such as Eitan Bar-Yosef, Amanda Burritt, and David Gange and David Ledger Lomas.4 Palestine was embedded within British Anglican culture largely as an imagined geography;5 this conception has been characterized by Bar-Yosef as involving two Jerusalems—the “here” and “there,” England’s idea of Palestine and Palestine itself.6 The development of archaeological tourism in Palestine during the Mandate drew increasing numbers of British visitors motivated by this British sense of affinity with Palestine, effectively leading to a collision of these two Jerusalems. British tourists brought with them, and imposed upon Palestine, British ideas of the Holy Land’s meaning and in turn reported their experiences of Palestine to a British audience, thereby shaping British attitudes toward Palestine in the Mandate.

Archaeology was, and is, a colonial discipline, a fact increasingly considered and explored by scholars in the field.7 Archaeology in Mandate Palestine functioned as what Bruce Trigger defines as “imperialist archaeology,” a discipline of control undertaken by states which exercise a great deal of political, economic, and cultural power over vast areas of the world.8 The imperialist archaeology of the British mandate lay the foundations for the nationalist and colonialist archaeology of Israel which would follow.9

The history of archeology in Palestine poses a fruitful research area as demonstrated by the work of scholars including Nadia Abu El-Haj, Amara Thornton, Sarah Irving, and Raphael Greenberg and Yannis Hamilakis, all of whom have contributed to a wider scholarly debate on the place of archaeology in the British Mandate.10 Tourism’s function as a colonial development and neocolonial practice has been examined as an area of academic enquiry in its own right;11 however, existent scholarship has yet to investigate the role of archaeological tourism in Mandate Palestine as a practice which combines different elements of colonialism—the movement of people, the control and expropriation of land, and control of the historical narrative. Dima Srouji states, in relation to the history of archaeology at Sabastiya, “Biblical narratives and archaeological strata have been more highly valued over the local narratives of the Palestinian residents for more than a century.”12 The reality of this colonial ideology clearly informed Mandate Palestine’s archaeological tourism industry, wherein the needs of tourists and visiting excavators, as Westerners and Britons, were prioritized over those of the predominantly Palestinian Arab residents of areas such as Sabastiya and al-Jura. The movement of significant numbers of British travelers, as tourist-pilgrims, into Palestine in the Mandate period therefore must be seen as part and parcel of British colonial domination of Palestine, a manifestation of a broader British desire to possess Palestine.13 The effects of archaeology’s use as part of colonial discourse14 can be seen today with Israel’s control of Palestinian land via archaeology and the national parks system,15 and the work of groups such as Elad who use archaeological tourism to garner public support for the settlement of Silwan and the displacement of Palestinians,16 with tourism itself being used as what Ofran has termed an “invisible settlement.”17 The British tourists examined in this article largely conform to the tourist-pilgrim model put forward by Cohen-Hattab and Bar: the tourist-pilgrim rested between secular tourism and strict religious pilgrimage, with motivations for travel including, but not restricted to, religion.18 These tourist-pilgrims focused not only on the traditional sites of pilgrimage such as the Church of the Holy Sepulcher but also on a more general experience of Palestine, which included the landscape and historical, cultural, and religious attractions.19 However, the religious aspect still loomed large over many Britons’ relationship with Palestine, with travelers sometimes explicitly emphasizing the religious nature of their visits, as expressed by Thomas Leigh from Liverpool who stated in a local newspaper interview that “my travels have confirmed my beliefs.”20

Two perspectives are examined in this paper: First, this article looks at British travelers drawn towards Palestine’s archaeological sites as tourist destinations and as sites which allowed them to more deeply connect with their religious faith via the “kairotic moment,” in which the past meets the present. The second story considers Mandate Palestine’s first director of antiquities, John Garstang. Garstang, who developed archaeological tourism in Palestine, clashed with the largely indifferent and sometimes hostile Mandate and Westminster governments which were reluctant to adequately fund archaeological institutions including the Department of Antiquities (DoA), Palestine Archaeological Museum (PAM), and the British School of Archaeology at Jerusalem (BSAJ).

JOHN GARSTANG AND THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTIQUITIES

Professor John Garstang, previously archaeological advisor to the British government in Sudan,21 served as the Mandate’s first director of antiquities and thus was a crucial figure in the development of archaeology and archaeological tourism. Despite his significant position, tensions grew between Garstang and the Mandate and Westminster Governments, ultimately leading to his resignation. Although his influence guided the development of archaeology in the Mandate during the so-called “Golden Age,” Garstang remains an underexplored figure.22 Garstang spearheaded the management of archaeology and ancient monuments in Palestine, an effort regarded both as a lynchpin of the Mandate’s modernizing drive as well as an example of the centrality of a universalist notion of history and heritage to the British imperial project and the formation of a “mandate identity,” as examined by Amara Thornton.23

Garstang’s story as an archaeologist in Palestine allows us to connect the world of the tourist-pilgrim with that of archaeology’s use as a tool of colonial power and how archaeological tourism facilitated this inequity. Garstang recalled his first visits to Palestine to tour the archaeological sites in terms reminiscent of tourist-pilgrims: for example, he described how memories of the bible stories from his youth came alive as he drove around Palestine.24 This anecdote suggests that the motivation of British archaeologists working in Palestine was not far removed from the motivation of tourist-pilgrims, and both tendencies indicate wider British cultural and religious connection with Palestine as the Holy Land. Garstang’s subsequent publications and work in Palestine predominantly focused on biblical archaeology, as seen with his series of articles entitled “Digging Sacred Soil,” which promoted the work of the DoA;25 his later work’s ties to biblical connections;26 and particularly his work at Jericho with Sir Charles Marston, a wealthy British industrialist who funded archaeology in Palestine to help prove the truth of the bible.27

Garstang submitted his official report to the government in 1919, suggesting that the “administration of Palestine involves in this respect responsibilities altogether exceptional,”28 a responsibility he would later accuse the government of neglecting. Out of Garstang’s report developed The Department of Antiquities (DoA),29 the Palestine Archaeological Museum (PAM),30 and the British School at Jerusalem (BSAJ).31 The ethos of antiquities policy, aligned with the overall aims of the Mandate system as being a supposedly more progressive form of colonialism,32 focused upon the advancement of territories “inhabited by people not yet able to stand by themselves,”33 with Western colonial powers such as Britain offering a guiding hand in said development.34 The report asserted archaeology’s importance to the Mandate by stating that anxieties around Palestine’s future under the Mandate were not solely concerned with economic issues “but mainly and more generally upon its religious and historical associations.”35 Garstang’s plans promoted archaeological tourism, proposing an idea of a tourist tax to help pay for the DoA’s work as well as an antiquities ticket which “shall entitle the said visitors to visit all the historical monuments of Palestine during the period of one month.”36 The Mandate Government rejected the tourist tax, as explained in a letter from Herbert Samuel, who suggested that implementing such a tax would be too complicated, partly because of religious pilgrims’ exempt status37—a valid concern as, given the religious motivations of many tourists, the lines between pilgrimage and tourism became increasingly blurred. In a report on the first eighteen months of the DoA, Garstang appeared optimistic, detailing the extensive progress already made and outlining plans for the future, including those for outdoor museums.38

However, after a few years, Garstang became disillusioned with not only archaeology in Palestine but also with the British Mandate’s approach itself, prompting his resignation in 1926. There is some confusion over Garstang’s resignation, confounded by the fact he was at the point holding down three jobs: director of the DoA, head of the BSAJ, and professor of archeology at The University of Liverpool. He first resigned his post as head of the BSAJ in May 1926 in order to take up his role as Director of Antiquities full time,39 but he would also resign as Director of Antiquities in December of the same year.40 W. F. Albright, head of the American school of Oriental Research in Jerusalem, later reflected on this departure and suggested that Garstang wanted to dedicate more time to excavation. However, private letters reveal that Garstang resigned largely due to the government’s refusal to renew a grant to the BSAJ.41 In one letter, Garstang states that there had been accusations that he “faked the balance sheet” of the school in order to make it eligible for certain funds.42 Earlier letters between the two indicate “there is more to this than meets the eye,” with Garstang suggesting a full investigation to uncover the truth43 and thus implying that Garstang had disagreed with the administration for some time.

Garstang’s clashes with the Mandate were not limited to archaeological approaches. His memoirs acknowledge his initial naïveté when he arrived in Jerusalem, recalling that he was “not fully aware of the political situation.”44 Yet in a few years Garstang became an outspoken critic of British policy in Palestine. In 1936 he published a pamphlet, reproduced in The Observer, that criticized the Mandate for deluding “the Jews with false hopes and the Arabs with vain promises.”45 Moreover, he attacked government policy in a public address, accusing the government of failing in their obligations towards Palestine’s Arab population.46 Garstang’s close friend and colleague W. J. Pythian-Adams, whom Garstang appointed keeper of the Palestine Archaeological Museum, also spoke out publicly and engaged in a debate in which he argued that British policy in Palestine deserved “the condemnation of all right-thinking people.”47 This statement suggests that the archaeological staff in Palestine felt at odds with the actions of the Mandate government beyond archaeological matters.

Garstang connected archaeological tourism in Palestine with the wider situation, describing his somewhat idealistic vision of a Palestine in which “the nationals of all races could enjoy the fruits of their labours and visitors from all countries could travel freely to see the Holy Places and historical monuments and perform their devotions in quiet,”48 was “swept aside, together with the fair name of Britain, by the pressure of dollar politics and Zionist territorial aspirations.”49 Garstang viewed archaeological tourism as a way to improve conditions in Palestine, envisaging what he would later describe as a “scheme of routes and tours, of guards trained in courtesy, of well conducted hotels and other features of an ordered service that would ensure these ends, and provide from tourist fees for the upkeep of the monuments if not for the whole administration of the country.”50 Garstang’s anger at the failure of his plans for archaeology permeates letters and memoirs written after his time in Palestine51 and suggests a genuine sense of disappointment that he had let the Palestinians down. Yet despite Garstang’s feelings that archaeology in Palestine under the Mandate did not live up to his expectations, archaeology did attract increasing numbers of tourists to Palestine, many from Britain who shared the same cultural and religious ardor reflected in Garstang’s work in biblical archaeology.

THE APPEAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY, KAIROS, AND THE PAST-IN-PRESENT

Understanding tourism in Palestine requires an examination of the motivations of British tourists as well as the appeal of Palestine as tourist destination. In their analysis of tourism in Palestine between 1850–1948, Cohen-Hattab and Katz discuss the role of the “attraction factor” in tourism, namely the primary elements which draw tourists to a place. Archaeology operated as a key attraction factor for Palestine and thus was publicized extensively, often by archaeologists themselves. As part of his role as Director of Antiquities, John Garstang wrote many articles in the British press about archaeology in Palestine52 and later wrote an appendix on the topic in the 1934 edition of Thomas Cook’s Traveller’s Handbook to Palestine and Syria.53 Increasing numbers of tourists were enough to be regarded as a nuisance by some archaeologists. For example, R. A. S. Macalister wrote to Garstang to complain about a proposed tour to Jerusalem in which “I am named as the attraction” (in reference to his excavations at Ophel just outside the Old City of Jerusalem from 1922–1924) and raise objections to his work “being hampered by uninvited mobs of trippers.”54 The excavations at Ophel are also listed as an attraction in an article in the Sphere.55

But why did antiquities and archaeology interest tourists so much? And why was the draw of Palestine different than that of other areas of archaeological interest such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the classical world? British fascination with Palestine, shaped by centuries of British artistic and cultural engagement, had been bolstered by a boom in publications about Palestine, with more accounts detailing European exploration of Palestine published in the 1800s than in the previous fifteen hundred years.56 This interest was rooted in Anglican Christianity and its connections to empire;57 archaeological tourists generally came from the same cultural background as the British archaeologist who worked in Palestine: largely educated, middle class, and Anglican Christian, and primarily interested in biblical sites. These tourists were drawn to sites such as the open-air museums, which offered a direct, material encounter with the past they could experience in the present. Such a melding of the past and present exemplifies what archeological theorist Michael Shanks has termed the “archaeological imagination”—how the archaeological becomes embedded within widespread ways of thinking about the past and how we relate to the past as it exists in the present, whether this is the material remains of the past or through memory and cultural history.58 Shanks’ theory centers on the notion of kairos, an ancient Greek conception of time in which the past and present meet in an opportune moment, the “kairotic moment,” which “is neither purely of the past nor the present, nor the re-presented past; it is the past-as-it-interrupts-the-present.”59 It is this moment of encounter, of experience, and of interaction with the past that unites the desires of archaeologists, driven by the moment of discovery, and of tourists who wish to directly explore the archaeological as represented in the kairos.60 An account of one British traveler, Mary Hatch, offers direct examples of Shanks’ characterization of kairos as the “past-as-it-interrupts-the-present.”61 Hatch described her experience in Palestine with the phrase, “That is the extraordinary thing about this Land—the past lives again before one’s eyes,”62 going on to detail a vivid scene of the present-day ruins filled with imagined characters from the past, specifically biblical characters such as Ahab, Jezebel, and Naaman. 63

Yet Shanks’ archaeological imagination does not consider religion in great depth, a regrettable omission as it is this religious aspect which distinguishes British tourists’ engagement with archaeology in Palestine as a special case. This paper will develop the concept of the archaeological imagination as a means to examine relationships between the past and present by adding a consideration of a specifically religious engagement with the past.

Indeed, this religious association drove tourists’ quest to establish a link with a specifically biblical past and thus a connection to God, as exemplified by Mary Hatch remarking “No wonder that on this spot God spoke to us,” while sitting on the walls of Jericho reading the story of Joshua.64 Therefore, alongside the archaeological imagination and kairos we can consider aspects of religious materiality, akin to the Protestant materiality explored by James Bielo, as related to Holy Land souvenirs, which seemingly offered direct access to the biblical past by way of their material links to the Holy Land.65 The appeal of archaeological tourism in Palestine lay in a potent combination of “kairotic” connection and religious materiality, experienced via the landscape and material remains of the past.

The biblification of Palestine via tourism exemplifies what Issam Nassar has termed “‘biblification’ in the service of colonialism;”66 popular images of Palestine at the time saw Palestinians and the Palestinian body subject to orientalist biblification, as scrutinized by Sary Zananiri.67 The landscape of Palestine was also seen in archaeological terms, with one account suggesting that “whatever else had changed the contour of the country had not.”68 Archaeological tourism represents how a process of biblification was enacted on the ground with orientalist ideas about Palestine and Palestinians, as brought to Palestine by British tourists who had absorbed them via the very images discussed in Nassar and Zananiri’s studies. This process of biblification was demonstrated by tourists in their attitudes towards Palestinians, who were treated as little more than props in a broader British drive to appropriate Palestine and its biblical past as part of Western history.69 Archaeological tourism encouraged British visitors to objectify Palestinians as part of this wider sought-after moment of kairos; the work of Nadia Abu El-Haj suggests that Europeans imposed a particular idea of nativeness on Palestinians and depicted them as a “living residue of the Biblical past.” 70Indeed, one traveler explained, “The people we meet on the roads are the living images in dress and deportment of the people we read about in the Bible.”71

THE APPEAL OF SEEING THE ANCIENT IN MODERN COMFORT

The material connection to the bible and the ancient was used to market Palestine as a tourist destination to Britons; for example, Thomas Cook encouraged visitors to “come and see in reality the hills and valleys and sites of cities you have heard about from earliest childhood.”72 John Garstang echoed this sentiment in recalling how visits to historic sites “awaken[ed] in me long dormant memories of the Bible stories heard in my youth.”73 Yet the appeal of archaeological tourism in Palestine for British tourists also relied on the ability to see ancient, biblical Palestine in modern comfort. As much as Palestine was sold via a barrage of biblified and orientalized imagery as a land that time forgot, it was also marketed as a land of contrasts in which the increasingly rapid pace of development under the British Mandate was highlighted. The British view of progress, and what constituted the modern, was one inextricably linked to Eurocentric views and orientalist assumptions. The British regarded advancement and modernity as phenomena imported to Palestine by the British or by European Jewish immigrants, who were seen as colonial middlemen.74 A photographic travel feature of 1936, which compared the new buildings of Tel Aviv with the Arab village of Kufr Malek, described the latter as “changed hardly at all since the days of the New Testament.”75 Interspersed with images of Arab fellahin and Bedouin, the travel feature demonstrates how these colonial ideals were expressed to a British audience and marketed to tourists as a “curious intermixture of the modern and the traditional and which provides the traveler with such an extraordinary sense of contrast.”76 The improvements in comfort for travelers were often contrasted with seemingly unfavorable travel in the Ottoman era. Thomas Leigh, notable for one of the most unusual and perhaps unintended engagements with the materiality of biblical Palestine when he became physically stuck in the Tomb of Lazarus,77 emphasized that travel in Palestine was now more comfortable and secure under the Mandate regime, declaring that a journey which once took him two days could now be completed in one with armed guards no longer necessary.78

The British Mandate repeatedly emphasized its dedication to archaeology as compared with the Ottoman regime, with Garstang’s report stating, “Popular sentiment at home and abroad, which under the almost passive negligence of the Turkish regime remained calm, will not tolerate any appearance of neglect now that the country is emancipated.”79 This notion of the British Mandate’s superiority to their Ottoman predecessors in all matters archaeological must be seen in the context of both British racism and orientalist attitudes, as well as a consequence of the post-war period in which the British sought to justify their military victory by asserting the Mandate’s moral and practical supremacy as compared to Ottoman Palestine.

Posters and printed advertisements often used orientalist images, which relied heavily upon stereotypical Western perceptions of the Middle East, to make Palestine appealing to potential British tourists. Advertisements offered assurances of comfortable travel and modern facilities, as exemplified by a poster for Palestine Railways boasting of “luxurious tourist trains” equipped with “modern passenger coaches.”80 Such appeals to comfort were about as common in travel advertisements as the clichéd orientalist imagery which emphasized the ancient and timeless; for example, Royal Mail Lines used a stylized image of men in long robes and headdresses sitting alongside camels to advertise a cruise to the Mediterranean, the Holy Land, and Egypt. 81 An article from 1929 sums up the appeal of the ancient and modern by suggesting that Palestine “offers the visitor not only the most sacred and interesting historical associations and a climate very grateful at this season, but also the most comfortable methods of transport,” and reassures readers that “even camping is practically done away with.”82 This presentation of the ancient and modern together can be seen as what Gregory terms “double geography,”83 which considers the dichotomy between the tourist’s need to travel in modern comfort yet explore an “untouched and timeless” land. The open-air museums, which offered tourists a convenient way to visit archaeological ruins, embodied this double geography as a modern tourist attraction that offered an immediate and immersive connection to the past.

OPEN-AIR MUSEUMS OF ASHKELON AND SAMARIA

Garstang’s 1919 plan for the archaeology of Palestine centered on a network of museums, including the main museum in Jerusalem and smaller local institutions (the latter focused upon “objects of peculiar local interest, archaeological pieces and sculptures not of unusual merit”84), and intended to ensure antiquities be cared for in the areas in which they were found. Local museums operated in Ashkelon, Caesarea, and Acre—locations which reflect European visitors’ interest in biblical, classical, and crusader era history. In practice, these museums comprised little more than open areas of exposed and excavated ruins, remains, and larger finds, such as statues and architectural fragments. In contrast to the more extensively studied Palestine Archaeological Museum, little information survives on these museums—Western guidebooks aimed at a Western audience, such as the American Colony Guide,85 offer only brief overviews; some later Mandate-era guidebooks exist for the sites such as the Umayyad Palace at Khirbat al-Mafjar near Jericho.86 However, the accounts of those who visited the sites, along with photographs, can offer a glimpse into the tourist experience and how the open-air museum enabled and encouraged engagement with kairos; two sites, Samaria, and Ashkelon, are briefly examined in this light.

These open-air museums exemplified archaeology’s institutionalization as a discipline that regulated not only archaeological remains but also the physical landscape, nodding to what El-Haj defines as a “legal and ideological transformation of the landscape as a whole.”87 The new antiquities laws required owners of land with noted archaeological finds to admit visitors, as demonstrated by the Roman Tomb at Sabastiya, which sat on the land of Abdul Ghani Abdulla Hasous, who was also appointed guard on his own land.88 The Antiquities Ordinance of October 1920 also stated that “equitable terms shall be fixed for expropriation, temporary or permanent, of lands which might be of historical or archaeological interest.”89 The land for the museum at Ashkelon belonged to Ahmed Ibn Ismail Basallah of al-Jura90 and was rented by the government around 1922. The government would eventually buy the land after complications arose from Basallah’s lack of paperwork to prove ownership, with Basallah not receiving any payment for his land until 1924.91 This incident is a stark example of how the needs of the government and, in turn, archeological tourists, were prioritized in law and in practice over the needs of local landowners.

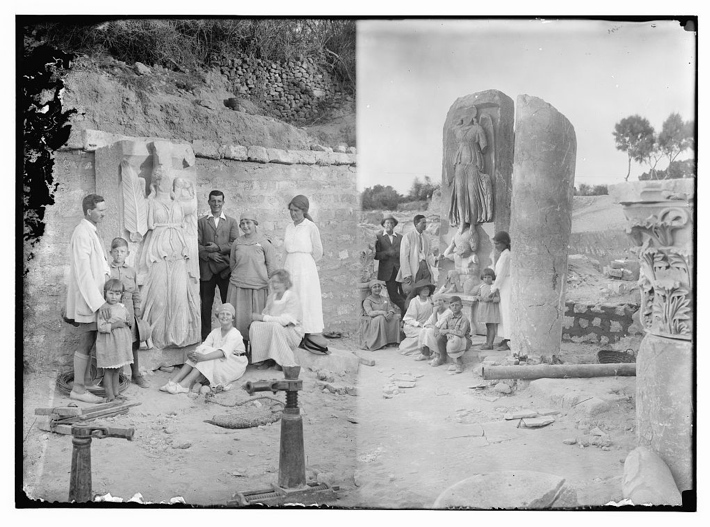

The museum at Ashkelon, which was situated in the village of al-Jura, is documented extensively in photographs catalogued in both the DoA archive92 and the American Colony photographic collection.93 Photographs in the American Colony archive show a tour group posing next to the Victory statue (Image 1), which Garstang excavated during the 1920–1921 season at Ashkelon, and visually represents the moment of kairos sought by archaeological tourists. The museum, walled off from the surrounding fields, occupied a small area, and in 1925 a road was planned between Majdal and Ashkelon to provide access for tourists “who might wish to visit the ruins,”94 illustrating how archaeological tourism impelled the development of infrastructure. A consequence of the inherent colonialism within archeological tourism was a Palestine desired and experienced by British tourists that was largely empty of Palestinians; thus, those who lived amongst the archaeology, who excavated it,95 and who worked in important roles such as Antiquities Guard,96 are mentioned only briefly and cast in a role of subaltern. However, we know that the museum at Ashkelon was overseen on a day-to-day basis by the antiquities guard, Mohammed Ismael Radi, whom we know was appointed in 1922 and held his post in 1943, though the exact length of his tenure remains unclear.97 Radi was a local man who owned a vineyard in the area.98 In addition to overseeing the museum in Ashkelon, Radi was responsible for reporting finds to the DoA and working as an intermediary figure between the DoA inspectors and villagers.99 However, in 1928, Ashkelon Musuem visitors accused Radi of stealing a bag. He was subsequently arrested and beaten by police.100 Fortunately for him, Radi’s good standing at the DoA was re-enforced by a letter of support from E. T. Richmond, Garstang’s successor as Director of Antiquities.101

Samaria, situated in the village of Sabastiya, was one of the largest and best-preserved ancient sites open to visitors. Samaria was excavated in 1908–1910 by teams from Harvard University and again in 1931–1935 by a joint expedition involving the British School of Archaeology at Jerusalem, the Hebrew University, and the Palestine Exploration Fund. A 1936 visitor guide to the site was published by the DoA,102 alongside other guides to sites such as Bethlehem and Acre. One account from William Basil Worsfold recalled the process of buying tickets at Samaria’s ruins from the man he describes as the “Arab guardian of the monuments.”103 Worsfold also reported a second guard who was present as they wandered about the excavations.104 The centrality of the biblical to tourist visits at these open-air museums is clear: one of the first things mentioned is the presence of a notice board “asserting the guardianship of the Palestine Department of Antiquities over the hill on which the Kings of Israel had built their palaces, and Herod raised a temple to Augustus.”105 Hatch also referred to the biblical context of Samaria, suggesting, “It is impossible to look at the ruins of Samaria without remembering the prophecy.”106 Israel continues to reference these biblical associations, particularly to the Kings of Israel, at present-day Samaria, an approach explored in the aforementioned work of Dima Srouji and Emek Shaveh.107

The open-air museums offered visitors almost unhampered access to landscape and archaeology, thereby fostering a connection to the same land of events in the bible. This concept of a living past with which one can physically interact offers a “kairotic” moment of archaeology in which a religious experience is enabled. Additionally, archaeological tourism and its surrounding infrastructure, seen with the creation of outdoor museums and the training of largely Palestinian Arab working-class staff to manage these sites,108 offers a concrete example of how the British attempted to instill a distinctly British view of heritage which involved a supposedly more “modern” respect for science and heritage.109

CONCLUSION

Archaeological tourism ideologically reformed Palestine through two avenues: via the physical excavation, exposure, and reshaping of the landscape; and via legal changes which designated areas “archaeological,” effectively changing the legislative and ideological relationship to the land. The Palestine sought by these British tourists represented the culmination of a centuries-long process that created an imagined and biblified perception of Palestine, in which an idealized image of the Holy Land was imposed upon Palestine through artistic and literary representations as well as geographic and archeological efforts, such as the Survey of Western Palestine.110

This particular phenomena offers an example of how, as Edward Said describes, “geography can be manipulated, invented, characterized quite apart from a site’s merely physical reality.”111 Archaeological tourism and the creation of open-air museums demonstrated how this imagined geography was created via the physical presence of archaeology, in which physical space and material remains were given new legal categories112 and the land reshaped in order to conform to a biblified ideal. The pursuit of the “kairotic” moment drove many to visit Palestine, and archaeological encounters formed part of a wider tourist experience primarily focused upon discovering the “Holy Land.” British tourists’ attraction to Palestine is perhaps best summed up by the words of Mary Hatch, who described herself as “immeasurably enriched by all the sacred memories we have carried away with us.”113 Such sentiment emphasizes not only the appeal of tourism to create memories but also represents how the movement of British tourists to Palestine was instrumental in the movement of ideas about and religious souvenirs from Palestine.114

The relationship between British tourists and Palestine was one underpinned by and enabled by the colonialism of the British Mandate, and the connection of British tourists to Palestine should be seen as part of a general appropriation of Palestine’s past as part of British cultural heritage. The increasing movement of British tourists into Palestine epitomizes the wider colonial occupation of Palestine by the Mandate. The archaeological tourism of the Mandate era ultimately laid the groundwork for the ideologically motivated nationalist Israeli archaeology and its links to present-day settler-colonialism, which often utilize the power of the archaeological imagination and kairos to create an emotional, religious, and cultural connection to the land, as seen with Silwan today.115

Garstang can be read as a man who represents a clash between the idealized version of Palestine and British colonial aims and the brutal reality. He is a contradictory figure who promoted a biblified, orientalized Palestine to tourists and an audience in Britain, yet spoke out against the increasing Zionist immigration and occupation encouraged by British policy and which biblical archaeology enabled. The open-air museums created by Garstang became venues where the “kairotic” moment could be enacted by British tourist-pilgrims. They offered intimate encounters with archeological remains and chances to reimagine landscape of ancient Palestine, becoming, in a sense, a physical manifestation of earlier nineteenth-century scriptural geographies.116 The open-air museums shared with these scriptural geographies a deep orientalism and a sense of possession; however, by encouraging the movement of British tourists into Palestine, they represent a physical representation of the British desire to possess Palestine and reshape it to fit the geopolitical and ideological aims of the British.

Archaeology and archaeological tourism created and imposed new interactions with the materiality of the past, one which largely severed the connection between the Palestine of the present and its archaeological material. To construct the past which interested the British tourists—and which was displayed to tourists via museums and archaeological sites—other histories were ignored, leading to what Uzi Baram describes as a “constructed void.”117 This void enabled the British to appropriate Palestine’s past as part of their own cultural heritage as a Christian nation which now occupied Palestine as a Mandatory power. What became of these open-air museums after the Mandate establishes their importance in the larger story of archaeology’s political uses and abuses; for example, both Sabastiya/Samaria and Ashkelon are Israeli national parks. Sabastiya, whilst in the West Bank, is under full control of the Israeli Archaeological Department of the Civil Administration.118 Palestinians’ relationship to their land was also forcibly changed via these open-air museums, as illustrated by the case of Ahmed Ibn Ismail Basallah of al-Jura as well as the reconceptualization of the al-Jura and Sabastiya villages into biblical Ashkeelon and Samaria, respectively. In both al-Jura, destroyed in the Nakba, the land now part of Ashkelon national park in Israel,119 and Sabastiya, where, in addition to the realities of life in the occupied West Bank, the benefits of archaeological tourism are denied to the Palestinian residents.120 This situation offers a stark reminder of the violence and inherent colonialism within the practice of archaeology that was developed in the Mandate and continue today.

Archaeology uncovered a biased Eurocentric narrative of history and displayed it to largely middle- and upper-class British tourists via sites such as open-air museums. These museums promoted Palestine as a cultural, religious, and educational destination for British tourists that was considered part of the cultural patrimony of the British Empire. Despite Garstang’s efforts to create tours beneficial to local communities, these programs did not come to fruition, and Garstang and the DoA were left to scrape by on a minimal budget. Tourism sought to increase income, yet it never developed enough to raise significant funds. This state of affairs led to antagonism between the DoA and Garstang in particular, as well as the British government (both the Mandate and at home in Westminster). Garstang’s memoirs of his time in Palestine suggest that his aims for tourism in particular were “swept aside, together with the fair name of Britain, by the pressure of dollar politics and Zionist territorial aspirations.”121 Ultimately, archaeological tourism functioned as one element of a wider infrastructure focused on producing a Palestine favorable to the West and detrimental to Palestine and the Palestinians.

NOTES

Peter Roger Stuart Moorey, “The Golden Age of Biblical Archaeology (1925–1948),” chap. 3 in A Century of Biblical Archaeology (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1991).↩︎

Kobi Cohen-Hattab, “Zionism, Tourism, and the Battle for Palestine: Tourism as a Political-Propaganda Tool,” Israel Studies 9, no. 1 (2004): 80.↩︎

Michael Berkowitz, “The Origins of Zionist Tourism in Mandate Palestine: Impressions (and Pointed Advice) from the West,” Public Archaeology 11, no. 4 (2012): 217–34.↩︎

Eitan Bar-Yosef, The Holy Land in English Culture, 1799–1917: Palestine and the Question of Orientalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Amanda Burritt, Visualising Britain’s Holy Land in the Nineteenth Century (Cham: Springer, 2020); David Gange and Michael Ledger-Lomas, eds., Cities of God: The Bible and Archaeology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).↩︎

The British relationship to Palestine can be considered an “imagined geography” as developed by Edward Said. See Said, “The Idea of Palestine in the West,” MERIP Reports, no. 70 (1978): 3–11, https://doi.org/10.2307/3011576; Said, “Palestine: Memory, Invention and Space,” in The Landscape of Palestine: Equivocal Poetry, eds. Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, Roger Heacock, and Khaled Nashef (Birzeit: Birzeit University Publications, 1999), 3–20.↩︎

Bar-Yosef, The Holy Land, 3.↩︎

The following works offer a brief overview of the field and general perspectives on archaeology and colonialism: Oscar Moro-Abadía, “The History of Archaeology as a ‘Colonial Discourse,’” Bulletin of the History of Archaeology 16, no. 2 (January 2006): 4–17; Margarita Díaz-Andreu, A World History of Nineteenth-Century Archaeology: Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Past (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); Díaz-Andreu, “Archaeology and Imperialism: From Nineteenth-Century New Imperialism to Twentieth-Century Decolonization,” in Unmasking Ideology in Imperial and Colonial Archaeology: Vocabulary, Symbols, and Legacy, eds. Bonnie Effros and Guolong Lai (Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, Los Angeles, 2018), 3–28. Works on archaeology and colonialism in the Middle East include: Ran Boytner, Lynn Swartz Dodd, and Bradley J. Parker, Controlling the Past, Owning the Future: The Political Uses of Archaeology in the Middle East (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2010); Lynn Meskell, Archaeology under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East (London: Routledge, 2002); Billie Melman, Empires of Antiquities: Modernity and the Rediscovery of the Ancient Near East, 1914–1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).↩︎

Bruce G. Trigger, “Alternative Archaeologies: Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist,” Man 19, no. 3 (1984): 363.↩︎

Nadia Abu El-Haj, Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-Fashioning in Israeli Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008); Raphael Greenberg and Yannis Hamilakis, Archaeology, Nation, and Race: Confronting the Past, Decolonizing the Future in Greece and Israel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022); Maria Theresia Starzmann, “Occupying the Past: Colonial Rule and Archaeological Practice in Israel/Palestine,” Archaeologies 9, no. 3 (December 2013): 546–71.↩︎

Nadia Abu El-Haj, “Producing (Arti) Facts: Archaeology and Power during the British Mandate of Palestine,” Israel Studies 7, no. 2 (2002): 33–61; Amara Thornton, “Tents, Tours, and Treks: Archaeologists, Antiquities Services, and Tourism in Mandate Palestine and Transjordan,” Public Archaeology 11, no. 4 (2012): 195–216; Sarah Irving, “The Kidnapping of ‘Abdullah al-Masri: Archaeology, Labor, and Power at ‘Atlit’,” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 91 (2022): 8–28; Greenberg and Hamilakis, Archaeology, Nation and Race..↩︎

Hazel Tucker, “Colonialism and Its Tourism Legacies,” in Handbook of Globalisation and Tourism, ed. Dallen J. Timothy (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019), 90–99.↩︎

Dima Srouji, “A Century of Subterranean Abuse in Sabastiya,” Jerusalem Quarterly 90 (2022): 72.↩︎

Butler, “Collectors, Crusaders, Carers,” 256.↩︎

Moro-Abadía, “The History of Archaeology as a ‘Colonial Discourse.’”↩︎

This issue is explored by Emek Shaveh, an Israeli NGO, which “object[s] to the fact that the ruins of the past have become a political tool in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and work to challenge those who use archaeological sites to dispossess disenfranchised communities.” Emek Shaveh, “About Us,” 2021, https://emekshaveh.org/en/about-us/. The following reports from Emek Shaveh are of particular relevance: Chemi Shiff, On Which Side Is the Grass Greener?: National Parks in Israel and the West Bank (Emek Shaveh, December 2017), https://emekshaveh.org/en/grass-greener_en/; Emek Shaveh, Ancient Sites Recruited in Battle Over Area C (Emek Shaveh, January 2021), https://emekshaveh.org/en/west-bank-2020/.↩︎

Settlement Watch, Peace Now, “Settlement Under the Guise of Tourism: The Elad Settler Organization in Silwan,” Peace Now, 10 December 2020, https://peacenow.org.il/en/settlement-under-the-guise-of-tourism-the-elad-settler-organization-in-silwan.↩︎

Hagit Ofran, “Invisible Settlements in Jerusalem,” Palestine - Israel Journal of Politics, Economics, and Culture 17, no. 1 (2011): 35–42.↩︎

Bar and Cohen-Hattab, “A New Kind of Pilgrimage,” 133.↩︎

Ibid., 133.↩︎

“Jammed in the Tomb of Lazarus: Merchant’s Adventures in the Holy Land,” The Liverpool Echo, 18 August 1927, 7.↩︎

John Garstang, “In Pursuit of Knowledge,” in Traveller’s Quest: Original Contributions Towards a Philosophy of Travel, ed. Maurice Albert Michael (London: William Hodge & Co., 1950), 205–28, 218. Garstang’s history of excavation in Egypt and Sudan, both areas under British imperial control, is testament to the imperialist nature of archaeology.↩︎

Whilst no comprehensive biography on Garstang has been published, works on Garstang’s archaeological career include: Francoise Rutland, The Lost Gallery: John Garstang and Turkey: A Postcolonial Reading (Liverpool: University of Liverpool, 2014); Felicity Cobbing, “John Garstang’s Excavations at Jericho: A Cautionary Tale,” STRATA: Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 27 (January 2009): 63–77; Anna Garnett “John Rankin and John Garstang: Funding Egyptology in a Pioneering Age.” In Forming Material Egypt: Proceedings of the International Conference, London, 20-21 May, 2013, 95-104, edited by P. Piacentini, C. Orsenigo, and S. Quirke. Milan: Pontremoli Editore, 2013. https://www.academia.edu/4034201/John_Rankin_and_John_Garstang_Funding_Egyptology_in_a_Pioneering_Age_Forming_Material_Egypt_Conference_University_College_London_2013_Precirculated_paper, László Török, Meroe City, an Ancient African Capital: John Garstang’s Excavations in the Sudan (London: Egypt Exploration Society, 1997).↩︎

Amara Thornton, “Tents, Tours, and Treks: Archaeologists, Antiquities Services, and Tourism in Mandate Palestine and Transjordan.”↩︎

Garstang, “In Pursuit of Knowledge,” 220.↩︎

The first of these was published in December 1922; see John Garstang, “Research in Palestine I,” Digging Sacred Soil, Illustrated London News, 2 December 1922. The last was published in December 1923; see Garstang, “Research in Palestine VII,” Digging Sacred Soil, Illustrated London News, 22 December 1923.↩︎

John Garstang, “The Story of Jericho: Further Light on the Biblical Narrative,” The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 58, no. 4 (January 1941): 368–72; Garstang, “History in The Bible,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 3, no. 3 (April 1944): 371–86.↩︎

Sir Charles Marston, The Bible Is True: The Lessons of the 1925–1934 Excavations in Bible Lands Summarized and Explained (Religious Book Club, 1938).↩︎

Garstang’s report on the antiquities of Palestine was submitted in 1919. John Garstang, memorandum, “Antiquities of Palestine,” submitted 30 March 1919, 8703/3, FO 141 687, The National Archives, London.↩︎

Jon Seligman, “The Departments of Antiquities and the Israel Antiquities Authority (1918–2006): The Jerusalem Experience,” in Unearthing Jerusalem: 150 Years of Archaeological Research in the Holy City, eds. Katharina Galor and Gideon Avni (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2011), 125–46.↩︎

Hamdan Taha, “Jerusalem’s Palestine Archaeological Museum,” in “Subaltern Archaeology, Part 2,” special issue, Jerusalem Quarterly 91 (2022): 59–78; Beatrice St. Laurent and Himmet Taşkömür, “The Imperial Museum of Antiquities in Jerusalem, 1890–1930: An Alternative Narrative,” Jerusalem Quarterly 55 (2013): 6–45.↩︎

Shimon Gibson, “British Archaeological Institutions in Mandatory Palestine, 1917–1948,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 131, no. 2 (1999): 115–43.↩︎

Peter Sluglett, “An Improvement on Colonialism? The ‘A’ Mandates and Their Legacy in the Middle East,” International Affairs 90, no. 2 (2014): 413–27.↩︎

The League of Nations, “The Covenant of the League of Nations (Including Amendments Adopted to December, 1924),” The Avalon Project: Documents in Law History and Diplomacy, accessed 20 August 2022, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/leagcov.asp.↩︎

Archaeology formed part of a wider project of development which is explored in the work of Jacob Norris. See Norris, Land of Progress: Palestine in the Age of Colonial Development, 1905–1948 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); Norris, “Transforming the Holy Land: The Ideology of Development and the British Mandate in Palestine,” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 8, no. 2 (2017): 269–86.↩︎

John Garstang, “Antiquities of Palestine: Memorandum. Submitted March 30th 1919 8703/3” (Memorandum, 30 March 1919), FO 141 687, British National Archives, Kew, 2.↩︎

Garstang, “Antiquities of Palestine,” 15.↩︎

Herbert Samuel to Secretary of State for the Colonies from High Commissioner of Palestine, “Re: Trans-Jordan Antiquities,” 13 February 1925, T161/56, British National Archives, Kew.↩︎

Garstang, “Eighteen Months’ Work of The Department of Antiquities for Palestine,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 54, no. 2 (April 1922): 57–62, https://doi.org/10.1179/peq.1922.54.2.57.↩︎

Garstang’s resignation is covered by Gibson, “British Archaeological Institutions in Mandatory Palestine, 1917–1948.” However, the matter appears to be more complex and requires more detailed archival study to fully untangle, which has been beyond the scope of this article.↩︎

“Minutes of the 28th. Ordinary Meeting Held on 21st. December, 1926 in the Department of Antiquities” (Jerusalem, 21 December 1926), Archaeological Advisory Board Minutes, 1st Jacket ATQ_1/26(431 / 288), Israeli Antiquities Authority, http://www.iaa-archives.org.il/zoom/zoom.aspx?folder_id=19348&type_id=&id=105132.↩︎

Garstang to Myres, “Re: British School at Jerusalem,” 12 November 1927, MSS. Myres 1–132, Special Collections, Bodleian Library, Oxford University.↩︎

Garstang to Myres, “Re: British School,” 12/11/1927, MSS. Myres 1–132, Special Collections, Bodleian Library, Oxford University.↩︎

Garstang to Myres, “Re: British School,” 1927.↩︎

Garstang, “In Pursuit of Knowledge,” 218.↩︎

Garstang, “Palestine in Peril: The Impossible Mandate,” Observer, 20 October 1936.↩︎

Garstang, “Arabs Let Down in Palestine,” Daily Mail, 13 August 1936.↩︎

“Palestine’s Problem: Arabs and Jews,” Mid-Ulster Mail, July 1936, British Newspaper Archive, https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002006/19360704/151/0007.↩︎

Garstang, “In Pursuit of Knowledge,” 220.↩︎

Ibid., 220.↩︎

Ibid., 220.↩︎

Ibid., 205–28.↩︎

Examples include a series called “Digging Sacred Soil,” the first of which is: Garstang, “Research in Palestine I.” Garstang also wrote about the excavations at Ashkelon; see John Garstang, “The Excavations at Askalon,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 54, no. 3 (1922): 112–19.↩︎

Thomas Cook and John Garstang, Traveller’s Handbook to Palestine, Syria &’Iraq: Thoroughly Rev. and Partially Rewritten by Christopher Lumby. With Eight Maps and Plans, by Bartholomew, Palestine Exploration Fund Map of Excavated Sites, and an Appendix with Two Sketch Maps on the Monuments (London: Simpkin & Marshall, 1934).↩︎

R. A. S. Macalister to Garstang, “Re: Ophel,” 23 July 1923, Ophel Excavations by P. E.F.1922/24, Israeli Antiquities Authority, https://www.iaa-archives.org.il/zoom/zoom.aspx?folder_id=205&type_id=&id=23592.↩︎

“The Sphere of Travel: Autumn in Palestine,” Sphere, 29 September 1923, British Newspaper Archive, https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0001861/19230929/025/0024.↩︎

Simon Goldhill, “Jerusalem,” in Cities of God: The Bible and Archaeology in Nineteenth-Century Britain, eds. David Gange and Michael Ledger-Lomas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 72, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511783647.003.↩︎

Joseph Hardwick, “An Anglican British World: The Church of England and the Expansion of the Settler Empire, c. 1790–1860,” in An Anglican British World (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017).↩︎

Michael Shanks, “The Archaeological Imagination,” in The Cambridge Handbook of the Imagination, ed. Anna Abraham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 47.↩︎

Shanks, The Archaeological Imagination (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2012), 134.↩︎

The notion of kairos is also explored by Nur Masalha in the introduction to Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History in which he relates kairos to how we remember and experience events. Masalha, Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History (London: Zed Books, 2018), 8.↩︎

Little is known about Hatch’s background, but she was traveling in the company of her friend, Ella Kate Crossley, who was involved with the India and Ceylon mission, which demonstrates the links between missionary activity, colonialism, and tourism in Palestine. See Ella Kate Crossley, Witnesses Unto Me: The Story of the Ceylon and India General Mission (London: Ceylon and India General Mission, 1907).↩︎

Mary A. Hatch, Travel Talks on the Holy Land (London: Marshall Bros, 1925), 75.↩︎

Hatch, Travel Talks on the Holy Land, 75.↩︎

Ibid., 36.↩︎

James S. Bielo, “Flower, Soil, Water, Stone: Biblical Landscape Items and Protestant Materiality,” Journal of Material Culture 23, no. 3 (18 June 2018): 368–87, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183518782718.↩︎

Issam Nassar, “‘Biblification’ in the Service of Colonialism: Jerusalem in Nineteenth‐century Photography,” Third Text 20, no. 3–4 (2006): 317–26, 317.↩︎

Sary Zananiri, “Indigeneity, Transgression and the Body: Orientalism and Biblification in the Popular Imaging of Palestinians,” Journal of Intercultural Studies 42, no. 6 (2021): 717–37.↩︎

“A Thousand Miles in Palestine,” Worthing Herald, 21 January 1928, 11.↩︎

Zananiri, “Indigeneity, Transgression and the Body,” 720.↩︎

El-Haj, Facts on the Ground, 38.↩︎

G. B. Duncan, On Sapphire Seas to Palestine: A Tour in the Holy Land of Today (Dundee: D. C. Thomson, 1927), 11–12.↩︎

“Thomas Cook Advertisement,” Times, 2 December 1930, 17.↩︎

Garstang, “In Pursuit of Knowledge,” 220.↩︎

Norris, “Transforming the Holy Land,” 269.↩︎

“Palestine: Land of Contrasts,” Sphere, 11 July 1936, 14–15.↩︎

“Palestine.”14.↩︎

“Jammed in the Tomb of Lazarus: Merchant’s Adventures in the Holy Land,” The Liverpool Echo, 18 August 1927, 7↩︎

“Jammed in the Tomb of Lazarus,” 7.↩︎

Garstang, “Antiquities of Palestine,” 2.↩︎

Palestine Railways, 1922, digital copy of original poster, The Palestine Poster Project Archives, https://www.palestineposterproject.org/poster/all-parts-of-palestine.↩︎

“Royal Mail Line Spring Cruising Programme,” advertisement, Illustrated London News, 20 November 1926, 33.↩︎

‘Warm Places for the Cold Weather’, The Sphere, 19 January 1929.↩︎

Derek Gregory, “Scripting Egypt: Orientalism and the Cultures of Travel,” in Writes of Passage: Reading Travel Writing, eds. James Duncan and Derek Gregory (Abingdon: Routledge, 2002), 119.↩︎

Garstang, “Eighteen Months’ Work,” 59.↩︎

G. Olaf Matson, The American Colony Palestine Guide, 3rd ed. (Jerusalem: American Colony Stores, 1930).↩︎

Dimitri Baramki, Guide to the Umayyad Palace at Khirbat Al Mafjar (Jerusalem: Government of Palestine, Dept. of Antiquities, 1947).↩︎

El-Haj, “Producing (Arti) Facts,” 36.↩︎

E. T. Richmond, “Sebastieh Antiquity Site, Roman Mausoleum,” 25 July 1932, Samaria (Sebastieh): Roman Mausoleum, file ATQ_2/59 (37 / 37), British Mandate Administrative ATQ Files, Israel Antiquities Authority Archives, http://www.iaa-archives.org.il/zoom/zoom.aspx?folder_id=3377&type_id=&id=42469.↩︎

“Antiquities Ordinance,” Official Gazette of the Government of Palestine 29, no. 15 (1920): 4–16.↩︎

John Garstang, “Memo Regarding Field Lease in Ascalon and Petition of Mohammed Ahmed Ayoub,” (Jersualem, 27 October 1922), Museum – Askalon, ATQ 1016(119 / 119), Israeli Antiquities Authority, http://www.iaa-archives.org.il/zoom/zoom.aspx?folder_id=249&type_id=&id=26066.↩︎

Letters concerning Basallah’s case are spreads across the DoA archives in a somewhat disorganized manner; they are primarily in the folder marked “Museum – Askalon, ATQ_1016(119 / 119)” and date between 1922–1924. Key documents include: a letter of 1922 mentions the intention to lease (see Garstang, “Memo Regarding Field Lease in Ascalon”);

a letter from Basallah expressing frustration at his situation (Ahmed Ibn Ismail Basallah, “Letter from Basallah to Director of Antiquities” (Letter, Al-Jura, 12 January 1923), Museum – Askalon, ATQ_1016(119 / 119), Israeli Antiquities Authority, http://www.iaa-archives.org.il/zoom/zoom.aspx?folder_id=249&type_id=&id=26082); and

a letter confirming the eventual sale dates to 1924 (A. Abramson to J. Garstang, “Antiquities Site at Ascalon,” 13 October 1924, Museum – Askalon, ATQ_1016(119 / 119), Israeli Antiquities Authority, https://www.iaa-archives.org.il/zoom/zoom.aspx?folder_id=249&type_id=&id=26129.↩︎

The archival sources for the museum at Ashkelon are spread across twelve folders in the British Mandate Administrative ATQ Files and British Mandate Scientific Record Files in the Israel Antiquities Authority Archives, which are located online at http://www.iaa-archives.org.il found under the search term “Ashkelon.”↩︎

Numerous photographs of the group’s outing to Ashkelon are found in the American Colony photographs in the Matson (G. Eric and Edith) Photograph Collection at the Library of Congress. The photographs are dated to between 1898 and 1946, but given that the photograph shows the group at the open-air museum, and the style of dress, they most likely date to the 1920s. The collection is available online, accessed 23 August 2022, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/matpc/colony.html.↩︎

Letter, “Road to Askalon,” 11 August 1925, Ascalon Antiquities PEF, File ATQ_2091 (29/29), British Mandate Administrative ATQ Files, Israel Antiquities Authority Archives. The 1930s/40s combined maps from Palestine Open Maps appear to confirm that the road was built; “al-Jura,” Palestine Open Maps, 02/08/2023 https://palopenmaps.org/en/maps/al-jura-gaza?basemap=15&overlay=pal1940&toggles=places.↩︎

In recent years there has been an increasing focus on the contributions of archaeological laborers in Palestine. See The Badè Museum of Biblical Archaeology, “Unsilencing the Archives The Laborers of the Tell En-Nasbeh Excavations (1926–1935),” 10 September 2021, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/collections/dc601d4d131145f88f828196860b8a44; Sarah Irving, “A Tale of Two Yusifs: Recovering Arab Agency in Palestine Exploration Fund Excavations 1890–1924,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 149, no. 3 (August 2017): 223–36.↩︎

Irving, “The Kidnapping of ‘Abdullah al-Masri,” 11–15.↩︎

Radi’s date of appointment and service up until 1928 is confirmed in the document: “Arrest of Antiquities Guard at Askalon,” 31 August 1928, ISA-Mandatory Organizations-Chief Secretary-000nwnq, Israel State Archives. His position in 1943 is confirmed by a letter to the Department of Antiquities, 5 November 1943, Ascalon – Jura, file ATQ 173 (3rd Jacket), British Mandate Administrative ATQ Files, Israel Antiquities Authority Archives.↩︎

J. Ory, “Extract from Inspector’s Report 22nd July 1930” (Report, 22 July 1930), Ascalon I, SRF 11(234 / 234), Israeli Antiquities Authority, http://www.iaa-archives.org.il/zoom/zoom.aspx?folder_id=11958&type_id=&id=72450.↩︎

Radi’s reports and documents concerning his career, such as letters and memos, can be found scattered across various subfolders inside the folder “Ashkleon” on the Israeli Antiquities website, http://www.iaa-archives.org.il/search.aspx?loc_id=8&type_id=.↩︎

The case is detailed in the folder: “Report Arrest of Antiquities Guard at Askalon” (31 August 1928), ISA-Mandatory Organizations-Chief Secretary-000nwnq, Israel State Archives, https://www.archives.gov.il/Archives/0b07170680031ec7/Files/0b07170680bbd158/00071706.81.D0.03.22.pdf.↩︎

“Letter from E. T. Richmond Subject: Antiquities Guard at Ascalon” (2 August 1928), in the folder “Report Arrest of Antiquities Guard at Askalon” (31 August 1928), ISA-Mandatory Organizations-Chief Secretary-000nwnq, Israel State Archives, https://www.archives.gov.il/Archives/0b07170680031ec7/Files/0b07170680bbd158/00071706.81.D0.03.22.pdf.↩︎

Hamilton, Guide to the Historical Site of Sebastieh.↩︎

William Basil Worsfold, Palestine of the Mandate (London: T. F. Unwin, 1925), 147.↩︎

Ibid., 147–48.↩︎

Ibid., 146.↩︎

Hatch, Travel Talks on the Holy Land, 74.↩︎

Srouji, “A Century of Subterranean Abuse”; Emek Shaveh, “Ancient Sites Recruited in Battle Over Area C.”↩︎

Irving, “The Kidnapping of ‘Abdullah al-Masri,” 10.↩︎

El-Haj, “Producing (Arti) Facts,” 36.↩︎

Claude Reignier Conder and Earl Horatio Herbert Kitchener, The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology, eds. Walter Besant and Edward Henry Palmer, vols. I, III (London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, 1881).↩︎

Said, “Palestine,” 8.↩︎

El-Haj, Facts on the Ground, 42–44.↩︎

Hatch, Travel Talks on the Holy Land, 111–12.↩︎

Bielo, “Flower, Soil, Water, Stone: Biblical Landscape Items and Protestant Materiality,” 376–78.↩︎

Settlement Watch, Peace Now, “Settlement Under the Guise of Tourism”; Joel Stokes, “‘Silence,’ Heritage, and Sumud in Silwan, East Jerusalem,” Jerusalem Quarterly 91 (2022): 105–20.↩︎

Edwin James Aiken, Scriptural Geography: Portraying the Holy Land, Tauris Historical Geographical Series, vol. 3 (London: I. B. Tauris, 2009).↩︎

Uzi Baram, “Entangled Objects from the Palestinian Past,” in A Historical Archaeology of the Ottoman Empire: Breaking New Ground, eds. Uzi Baram and Lynda Carroll, Contributions to Global Historical Archaeology (New York: Springer, 2002), 139.↩︎

Srouji, “A Century of Subterranean Abuse,” 61.↩︎

“al-Jura (Jerusalem),” Zochrot, accessed 26 October 2020, https://zochrot.org/en/village/49070.↩︎

Jafar Subhi Suleiman Abahre and Samer Hatem Raddad, “Impact of Political Factor on the Tourism Development in Palestine: Case Study of Sabastiya Village,” American Journal of Tourism Management 5, no. 2 (2016): 29–35.↩︎

Garstang, “In Pursuit of Knowledge,” 220.

Hatch, Travel Talks on the Holy Land, 111–12.↩︎