Joshua Donovan1

THE SYRO-LEBANESE FROM “SYRIBAN”: NOSTALGIA, PARTITION, AND COEXISTENCE IN EVELINE BUSTROS’ IMAGINED HOMELAND2

Abstract

This article offers new insights into nostalgia and nationalism in the Syrian/Lebanese diaspora through the literary, artistic, and philanthropic work of Eveline Bustros (1878–1971). It relies on her underexplored published works as well as a rare collection of Bustros’ personal correspondence, journals, photographs, and speeches compiled by her family. After World War I, the French partitioned Bilad al-Sham into multiple polities and inaugurated a new citizenship regime dividing erstwhile Ottoman Syrians into categories of “Syrian” and “Lebanese.” In the midst of these geopolitical changes, Bustros and her family lived in Paris, where she began her celebrated literary career. Although she was a committed Lebanese nationalist, Bustros articulated hybrid notions of identity that elided distinctions between “Syrians” and “Lebanese.” Confronted with reports of sectarian violence during the Syrian Revolt (1925–1927), Bustros used her writings to grapple with the feasibility of peaceful coexistence in the Levant. Upon returning to Lebanon, she became a leading member in Lebanon’s early feminist movement while maintaining deep, affective connections to the Syrian interior. Bustros’ life and work complicate understandings of diasporic nationalism and nostalgia by highlighting fluid identities shaped by multidirectional bourgeois mobility, inviting scholars to consider nationalisms beyond the confines of the nation-state.

خلاصة

يقدم هذا المقال رؤى جديدة حول الحنين إلى الماضي والقومية في الانتشار السوري / اللبناني من خلال الأعمال الأدبية والفنية والخيرية لإفلين بسترس (1878–1971). يعتمد المقال على أعمالها المنشورة والتي لم تُستخدم حتى الآن بشكل وافي، بالإضافة إلى مجموعة نادرة من المراسلات الشخصية والمجلات والصور والخطب التي جمعتها عائلتها. بعد الحرب العالمية الأولى، قسّم الفرنسيون بلاد الشام إلى عدة أنظمة سياسية وأطلقوا نظامًا جديدًا للمواطنة يقسم السوريين العثمانيين السابقين إلى فئات "سوري" و "لبناني". في خضم هذه التغيرات الجيوسياسية، عاشت بسترس وعائلتها في باريس، حيث بدأت مسيرتها الأدبية الشهيرة. على الرغم من أنها كانت قومية لبنانية ملتزمة، فقد أوضحت بسترس مفاهيم هجينة للهوية استبعدت التمييز بين "السوريين" و "اللبنانيين". في مواجهة تقارير العنف الطائفي أثناء الثورة السورية (1925–1927)، استخدمت بسترس كتاباتها للتعامل مع جدوى التعايش السلمي في بلاد الشام. عند عودتها إلى لبنان، أصبحت عضوًا قياديًا في الحركة النسوية الأولى في لبنان مع الحفاظ على علاقات عميقة وعاطفية مع الداخل السوري. إن حياة وأعمال بسترس تعقّد مفاهيم قومية الانتشار والحنين إلى الماضي من خلال تسليط الضوء على الهويات المتغيرة التي شكلها الحراك البرجوازي المتعدد الاتجاهات، وتدفع الباحثين للتأمل في تكوين القوميات خارج حدود الدولة القومية.

INTRODUCTION

You don’t know my mountain . . .

Like the sun,

The sky and even the streams only illuminate and are moved when they join the two lands [Syria and Lebanon].

The fertility of the plain enticing the mountain.

The freshness of the mountain necessary for the plain.

The community of one language and its glories . . .

How can you measure on our hearts the action of so many attractions, Mohammad,

If you don’t evaluate the irreducibility of the obstacles which, alas, separate us?3

-Evelyn Bustros, “Fredons” (1929)-

1919 was a year of tremendous upheaval and uncertainty in the Levant. The end of World War I brought with it the abrupt end of over four hundred years of Ottoman rule in the Eastern Mediterranean. Millions of Ottoman subjects effectively lost their citizenship as the 1869 Ottoman Nationality Law became defunct. This included hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children from Ottoman Syria who had emigrated to Africa, Europe, and the Americas beginning in the late nineteenth century.4 This raised the obvious but fraught question: What would happen next? Many erstwhile Ottoman Syrian migrants living in the mahjar sprang into action, drafting articles, pamphlets, petitions, and telegrams proffering different visions of what Greater Syria ought to look like after the war.5

As European and American diplomats met in Versailles to craft a postwar settlement that would decide the fate of millions around the world, prominent politicians, journalists, religious leaders, and thinkers from Greater Syria met to decide how to organize and respond.6 Some, including Hashemite Emir Faysal and Maronite Patriarch Ilyas Huwayyik, traveled from the Levant to Paris themselves to present Western officials with specific proposals and visions for the postwar Middle East.7 They were hardly alone. That summer, the city had become something of an “anti-imperial metropolis,” to borrow Michael Goebels’ phrase, as formal delegations and informal groups of people from the global South came to make their voices heard. Before long, interwar Paris became home to colonized peoples drawn from every corner of France’s vast and growing empire from Algeria to Indochina and the Levant, as well as others, including Indian nationalists, Chinese Marxists, Latin American intellectuals, and African American literati, who all traveled to metropolitan Paris to pursue work, education, or activism.8

That same year, Eveline Bustros (1878–1971) also arrived in Paris with her husband, Gabriel, and their son, Fadi. She stayed for over a decade before returning to her natal home of Beirut. While she was primarily known for her literary and philanthropic work, Bustros was not completely aloof to the political climate in Paris. Her brothers, Jean and Michel, traveled between France, Egypt, and Beirut, working closely with French officials. Bustros, herself, enjoyed cordial relationships with French generals Maxime Weygand, Henri Gouraud, and Georges Catroux, who would each take a turn as High Commissioner of the Levant. On the anticolonial side of the political spectrum, Bustros was friends with Shakib Arslan, a prominent Druze activist who opposed France’s occupation and partitioning of the Levant. From his diasporic base in Geneva, he fought for a unified Syrian state that would have included Lebanon and historic Palestine.9 For her part, Bustros voiced humanitarian concerns during the Syrian Revolt (1925–27) to French general Georges Catroux, who politely but firmly dismissed her concerns.10 However, Bustros spent most of her time in Paris in a rarefied social circle of cosmopolitan Beiruti expats who were often joined by elites making annual pilgrimages to the colonial metropole in order to indulge in the latest fashions and reaffirm their preeminent social statuses back home and abroad.11 Inspired both by Parisian salon culture and the efflorescent Arabic Nahda, or literary renaissance, Bustros also cultivated a budding literary career. This study builds on recent work examining the politically important work of Syrian and Lebanese women in diaspora by expanding traditional understandings of what constitutes the “political” to include cultural production, philanthropy, historical memory, and nostalgia—each of which features prominently in Bustros’ life and work.12

While she did not pen fiery political tracts demanding specific territorial arrangements in the Levant, Bustros’ interwar work represented a distinct social and political vision for the Levant that has been largely overlooked. Scholars have detailed influential organizations like Shukri Ghanim’s Comité Central Syrien and the Lebanese League of Progress, which demanded a separate, independent Lebanon, as well as rival groups like Khalil Sa’adeh’s Syrian Union Society, which instead called for a single, federated Syrian state.13 The Treaty of Lausanne (1923) further enshrined distinctions between “Syrians” and “Lebanese” by making them legal categories. France, in turn, imposed a new two-state citizenship regime on Syro-Lebanese émigrés, insisting that they register as either “Syrians” or “Lebanese” based on their birthplace or their father’s birthplace.14 And yet, even as partition became a fait accompli over the 1920s and 1930s, affective ties rooted in an Ottoman political order that transcended postwar political boundaries endured, especially in the diaspora. French consular officials complained that many “Syrians” and “Lebanese” were slow to accept their new citizenships “despite all the propaganda that the legation and the consulates had continued for months.”15 In a similar and more lasting vein, diaspora institutions like São Paulo’s Hospital Sírio-Libanés (est. 1921), newspapers like the Buenos Aires-based El Diario Siriolibanés (est. 1929), and civic organizations like the Club Sirio Libanés Honor Y Patria (est. 1932) blurred territorial distinctions between Syria and Lebanon.16 What are we to make of this? Because Bustros herself elided the national borders of Syria and Lebanon in her fiction, art, and activism, she offers a useful window into this prevalent yet undertheorized feature of Syro-Lebanese diasporic nationalism.

Nation-state boundaries do not always align with the boundaries of homelands imagined in diaspora. In his study of Armenian diaspora communities, for example, historian Simon Payaslian described “a fundamental clash between the imagined and real Armenia” and “disillusionment” with both the Armenian state’s circumscribed borders and Soviet policies toward repatriates.17 This mismatch, coupled with growing attachments to new host countries, can contribute to a “de-territorialized” or “trans-statist” nationalism in diaspora, where “the imagined homeland transforms into a mere cultural reproduction, an invention, of de-territorialized imagination.”18 This may aptly describe the aforementioned “Syro-Lebanese” organizations, but Eveline Bustros complicates the story. On the one hand, her writing, artistic production, and early activism often took the form of affective expressions of patriotism and a shared cultural heritage that blurred political boundaries. On the other hand, she strongly supported the creation of a separate Lebanese state and, in the aftermath of sectarian violence during the Syrian Revolt, was skeptical about the prospects of peaceful coexistence between Muslims, Christians, and Druze. Including Bustros in the analysis of conflicting Syro-Lebanese nationalisms during the interwar period unsettles methodological nationalism, which sees the creation of Syrian and Lebanese nation-states as straightforward and inevitable. Instead, her oeuvre invites us to understand trans-statist expressions of nationalism as serious efforts to reconcile nostalgia for one’s old homeland with tumultuous political developments that have irrevocably changed that homeland.19

After offering a brief biographical sketch of Bustros, I analyze the two major works she wrote and published while living in Paris: a historical novel, La Main d’Allah (1926), and a short, fictionalized dialogue called “Fredons” (1929). Like her later novels, she published both of these works in French.20 Then, building on scholarship that considers how migration experiences shaped the lives and perspectives of people who repatriated, I follow Bustros back to Beirut in the 1930s. Here, I consider her early philanthropic work with Syriban (a portmanteau of “La Syrie” and “Le Liban”), an organization she founded to revive “traditional” handicrafts and bring female artisans from the Syrian interior into the modern capitalist economy that had taken root in Beirut. I conclude by examining a physical manifestation of Bustros’ nostalgic, trans-statist nationalism: namely, her vibrant “costumes orientaux,” featured first in lavish parties in Beirut and then displayed at the Lebanese pavilion for the 1939–1940 World’s Fair in New York City.

With subtle discursive turns and artistic touches, Bustros’ nationalism blurred and transgressed the political boundaries erected between Syria and Lebanon by French partition and the social boundaries separating the region’s many religious communities which sharpened under French colonial rule, even while such boundaries remained omnipresent in her overall political outlook. As Bustros navigated the multiple layers of her identity as a wealthy, cosmopolitan, Beiruti Greek Orthodox Christian woman who lived abroad for several years, I argue that her diasporic writings evoked a nostalgia for a time before colonial partition and sectarian violence that would carry over into her later activism in Beirut. From a Parisian apartment physically removed from the daily realities of partition and colonial rule, Bustros crafted what Salman Rushdie termed an “imaginary homeland,” in which categories like “Lebanese,” “Syrian,” “Christian,” and “Muslim” did not carry the kind of baggage they often did in the interwar Levant.21 She also used her distinctive nationalism to grapple with the legacy of sectarian violence in her homeland, including attacks on Christian villages during the Syrian Revolt. Both in her personal and professional life, Bustros longed for a political system that would allow the Levant’s diverse religious communities to coexist in a shared waṭan (homeland), even if that meant adopting the sectarian political logics of the French High Commission. Finally, Bustros insisted on a place for women in the Levant. Ultimately, her work was Janus-faced—looking backward to a precolonial Ottoman habitus while simultaneously grappling with the new social and political realities of French colonial rule.

WRITING “PHOENICIA” INTO ISLAMIC HISTORY: THE NOSTALGIC GEOGRAPHY OF LA MAIN D’ALLAH

Eveline Bustros was born in Beirut during a time when the small city was becoming increasingly integrated into networks of global capitalism. She was the daughter of two extraordinarily wealthy and influential Greek Orthodox Christian families: the Tuenis and the Sursocks, who had extensive financial ties to European markets and played leading roles in their city’s social and political scene. She traveled to France for the first time in 1899, where she took a painting course and lived with her brother, Jean, who was stationed abroad as an Ottoman diplomat. There, Bustros quickly honed her French language skills, composing short poems and journaling in French. She returned to Beirut and married Gabriel Bustros, an homme d’affaires from a third prominent Orthodox family, in 1904. As an Ottoman subject with considerable financial means, Bustros traveled freely and frequently throughout the Eastern Mediterranean.22

After the outbreak of World War I, Bustros fled to Egypt with her husband and their young son.23 While in Egypt, Bustros joined a literary society called La Société des Auteurs Libanais de Langue Français, which was comprised of predominantly Christian, Francophone, and Francophile Lebanese expats. As historian Asher Kaufmann quipped, the group “had mastered French as if they were indeed les Français du Levant.”24 Bustros also contributed to Ébauches, a literary magazine published in Alexandria by two of the society’s prominent members: banker Michel Chiha and journalist Hector Klat. Both would remain lifelong friends of Bustros. This milieu was resolutely committed to the creation of an independent Lebanese state—a “Grand Liban” separate from Syria and Palestine. They often justified the separation by drawing on an ancient Phoenician past, which they argued was culturally and even racially distinct from that of their Arab neighbors.25 Although Bustros largely eschewed overtly Phoenician themes in her writing, her time in Egypt undoubtedly shaped and reinforced her commitment to Lebanese nationalism.

In 1919, Bustros moved to Paris, where she began to research and write her first novel.26 While she was away, the social and political fabric of her homeland changed drastically. Her writings demonstrate support for French colonial policies, including partitioning the Levant according to a sectarian framework—with states or statelets for several “minority” religious communities—and creating a separate Lebanese Republic. At the same time, she also understood that many of her fellow countrymen felt differently and was committed to maintaining friendships beyond those who aligned with her ideologically.27 With her debut novel, La Main d’Allah (The Hand of God), which she published in Paris in 1926, Eveline Bustros accomplished quite a feat: in the midst of the tumultuous Syrian Revolt, Bustros penned a book that won the exuberant admiration of French authorities, ardent Lebanists, and Syrian nationalists alike.28

Unlike some of her Lebanese nationalist contemporaries whose literary production focused on a Phoenician Lebanon (like Klat, Chiha, and Jacques Tabet), Bustros drew her inspiration from an early episode in Arab Islamic history.29 La Main d’Allah presents a dramatized account of Caliph Mu’awiya I (r. 661–680 CE) and his infamous son, Yazid I (r. 680–683 CE). The plot centers around Mu’awiya’s ambition to create a hereditary dynasty and pass his title of caliph onto Yazid. The move was ultimately successful and led to the founding of the Umayyad Dynasty, but it was also unprecedented and bitterly divisive. Among other things, it inaugurated a civil war within the early Muslim community that raged for over a decade and claimed the life of the Prophet’s grandson, Husayn, in 680 CE.30 By writing a historical novel inspired by Islamic history, Bustros followed in the footsteps of Jurji Zaydan (1861–1914), a prolific luminary of the Arabic Nahda who, like Bustros, was born in Beirut to a Greek Orthodox family and moved to Egypt to pursue his literary career.31 Even to non-Arab readers, Bustros’ novel evoked a sense of authenticity. A French literary critic gushed in his review of the book that “it has been such a long time since we have so thoroughly relished in a French book all the enchantment of Oriental poetry.”32

According to her private notes and the novel’s preface, Bustros drew much of her historical context from the work of Henri Lammens, a prominent French Jesuit Orientalist who, upon reading La Main d’Allah, heaped effusive praise on its author.33 However, Bustros’ version of this tumultuous period centers on a fictional woman named Oraïnab, whose beauty was renowned and unparalleled in her day. She was so beautiful, in fact, that Caliph Mu’awiya compares her to a diamond while comparing his own daughter, Hind, to ebony (La Main d’Allah, 152–58). Based on her reputation alone, the profligate and impulsive Yazid falls madly in love with Oraïnab. Unfortunately for him, she is already married to Ben Salam, the governor of Kufa (Iraq) and the son of an early Jewish convert to Islam.34 To help his son, Mu’awiya tricks Ben Salam into divorcing Oraïnab, but rather than marrying Yazid, Oraïnab chooses to marry Husayn, who had taken pity on her and offered to save her from Umayyad treachery. This, in turn, fuels Yazid’s hatred for Husayn (183–99, 221–24). Bustros’ account of the seventh-century civil war that tore the Muslim community apart turned less on theological or philosophical principles about communal leadership than on greed, ego, and lust. By the end of the novel, the reader is left feeling little pity for any of the unscrupulous men in Oraïnab’s life (with the notable exception of Husayn). Bustros concludes by returning to the question of theodicy which she had also posed at the beginning of her book (2), wondering who could know the mysterious ways and secrets of God. Why, she wondered, would an almighty and merciful God not spare his faithful from the iniquities of Yazid (238–39)?

Not only did the subject matter of La Main d’Allah resemble Nahda literature but it also echoed what Elizabeth Holt has called “a botanical obsession” prevalent in many of Beirut’s earliest Arabic newspapers and magazines like Khalil al-Khuri’s Hadiqat al-Akhbar (The Garden of News, est. 1858), Yusuf al-Shalafun’s al-Zahra (The Flower, est. 1870), and Salim al-Bustani’s al-Jinan (The Gardens, est. 1870) and al-Junayna (The Little Garden, est. 1871).35 In seminal novels like Khalil al-Khuri’s Kharabat Surriyya (The Ruins of Syria, 1860) and especially Salim al-Bustani’s al-Huyam fi al-Jinan al-Sham (Passion in the Gardens of Damascus, 1870), scenic descriptions of Greater Syria were meant to inspire a sense of patriotism and awe for readers.36 Writing from the diaspora, Bustros similarly invited her readers to remember their homeland with fondness and pride.

If, as Tasnim Qutait argues, “nostalgic tropes [from Arabic literature] cross linguistic boundaries,” then the nostalgic imagery Bustros uses in La Main d’Allah also cross the new national boundaries in the Levant as well.37 Telling a tale centuries before the emergence of nation-states, Bustros conspicuously dwells on the borderlands of modern Syria and Lebanon. Perhaps most notably, Bustros details a trip taken by two companions of the Prophet, Abu Hurayra and Abu Darda, from Damascus to Yazid’s residence in Deir Moranne near Mount Qasioun. The pair pass through “‘the gate of heaven’ by which Damascus contemplates the Anti-Lebanon mountain range,” cross a drawbridge built over the Barada River, and turn toward a countryside “lauded by the poets” (72). The interstitial space between “Syrian” and “Lebanese” mountains were home to “paradisiacal gardens” which “opened widely like a generous hand” (72–73). With vivacious prose, Bustros continues: “It was a suite of orchids, with trees disappearing under flowers so dense that they looked like veils fallen from the bare sky to clothe it. Hedges composed of myrtle and poplars bathing in the channels that separated the estates crisscrossing this space of verdant and thrilling galleries” (73). As he stares off into the distance of the rolling Syro-Lebanese countryside, Abu Hurayra exclaims, “Truly . . . God stripped his paradise to adorn these parts!” (74).

This idyllic scene in particular captured the attention of one of her readers: a Syro-Lebanese man named B. Lebnan, who wrote to Bustros with glowing praise. Penned in French, Lebnan’s letter offers tantalizingly few biographical details. We can discern that he worked as an engineer in the small Egyptian town of Armant, near Luxor. The letter also suggests he was born in a village along the Syrian-Lebanese border before there was one, but we do not learn his birthplace, citizenship status, or views on the partitioning of the Levant. Nevertheless, La Main d’Allah struck a chord with him. Discussing Abu Hurayra and Abu Dardaa’s trip, Lebnan wrote:

I spent exquisite hours reading your delicious work; for we who live far away, the evocation of this florid corner of the Orient where we were born and raised, awakened in our spirit tender memories of our childhood, when all youths descended from our arid mountains to go in search of instruction and knowledge in the large scholarly institutions of the city; Damascus and its perfumed gardens, Barada and its florid valley, we often think of it as if in a dream.38

Lebnan did not specify where he grew up, except to say that it was the same “florid corner of the Orient” described by Bustros in her book. For him, La Main d’Allah “awaken[ed]” nationalist “memories . . . of a glorious and eminently interesting era in the life of our people which had faded into oblivion.”39 Injecting modern politics into his experience reading the novel, he lamented that Bustros’ novel spoke of a distant time in which “the Turks had not passed by our country and had not yet destroyed in the Arab nation that which was the best.”40 In other words, La Main d’Allah was a golden age from which Lebnan hoped his countrymen could take lessons as they navigated their post-Ottoman world.41

Bustros also blurred lines between Syrians and Lebanese in her novel by reminding readers that Lebanon was a part of the social and economic fabric of the Umayyad caliphate (as were what one might anachronistically call “Lebanese people”). This is particularly evident in a lavish and debaucherous scene at Yazid’s home in Deir Moranne. In her account, the prince’s residence had been built from pink stones from Lebanon, and he served his guests wine in amphorae from Lebanon (89, 102–7). Lebanon also featured in Yazid’s poetic yearnings for Oraïnab, whose “luscious lips,” he claims, “were melty and sweet like the figs of Lebanon” (84). Syria and Lebanon were not only integrated by goods in La Main d’Allah but also by people. When discussing the extent of Prince Yazid’s popularity in the early Islamic community, Bustros faithfully includes Saida along with Homs, Antioch, “the desert,” and Damascus (201). And while individual figures born in present-day Lebanon did not feature prominently in Lammens’ account of early Islamic history (or in La Main d’Allah), Bustros pointedly notes the presence of merchants in Damascus, almost all of whom “belonged to that race of Phoenician merchants, who only dream of peace and profits” (112). Here, she invokes a common trope about the entrepreneurial acumen of the seafaring Phoenicians but also weaves them seamlessly into a diverse Arab and Islamic social fabric.42

The geographic slippages in La Main d’Allah carried over to some of the novel’s reviews as well. In Souday’s aforementioned review, the critic began by introducing “Mme. Eveline Bustros” as “a Syrian who writes in French.” To provide some context to readers, he then boasted that “cultured Syrians did not wait for a French mandate before learning our language.”43 That Bustros was legally “Lebanese” by that time was a distinction apparently lost on him, even after having met and corresponded with Bustros personally in France.44 And although Bustros’ friend Shakib Arslan would have understood Bustros’ legal status as “Lebanese” under the Treaty of Lausanne, he too was eager to claim her as Syrian, writing to her in a personal letter, “My heart leapt with joy to see a Syrian woman [dame]—a compatriot of mine—succeed in writing such beautiful novels in French on a subject taken entirely from Arab history.”45 There is no indication that Bustros corrected either man.

BUSTROS AND THE ANTI-SECTARIAN TRADITION

Although the nationalist nostalgia of La Main d’Allah may have spoken more to affect than borders, Bustros’ novel was not apolitical. To the contrary, she positioned her novel within what Ussama Makdisi has called the “anti-sectarian tradition” in the Middle East.46 As previously mentioned, Bustros wrote her novel during a turbulent time in the Levant as French colonial policies of divide-and-rule inflamed tensions between different communities. Because borders were drawn to maximize the political power of certain “minority” groups at the expense of others, resistance to French colonialism sometimes took on a sectarian dimension. Shortly before she wrote La Main d’Allah, things had become particularly tense. In the summer of 1925, Druze leader Sultan al-Atrash launched a revolt against French colonial rule in Syria, which quickly spread throughout the Levant, including the fertile valley of Wadi al-Taym in Lebanon.47 While the fighting was initially between Druze tribal leaders and the French, Christian villagers in Rashaya, Hasbaya, and Marja’yun found themselves caught in the crossfire. In Rashaya alone, hundreds of Christian homes were destroyed and over a dozen Christian villagers were killed. While some blamed the French, Reem Bailony has shown that many prominent journalists in the mahjar framed the violence in sectarian terms. To many Christian Lebanese nationalists, the violence demonstrated the need for an independent Lebanon designed (at least in theory) to be a majority-Christian polity.48

La Main d’Allah was designed, among other things, to speak to the fraught political moment that had engulfed her homeland and her co-religionists. Like the book’s geographical slippages, the peaceful coexistence between Christians, Muslims, and Jews is subtle but unmistakable. Bustros does not present an ahistorical utopia; her novel features several instances of sectarian stereotypes and name-calling, for example. However, she depicts early Islamic Syria as a diverse social mosaic both through her use of geography and characters in the novel. One of the most striking examples of this occurs shortly after another former companion of the Prophet Muhammad, al-Mughira, flees his post as governor of Kufa to avoid an outbreak of plague and arrives in Damascus to serve as an advisor to Mu’awiya.49 One day, as he heads to the palace to deliver some good news, al-Mughira pauses at Saint John’s Cathedral and thinks to himself: “The holy house—a church on one side, a mosque on the other—under a roof shared by two sects [deux sectes], was a favorable place for the news” (40).50 Al-Mughira’s brief but noteworthy endorsement of an intercommunal space that actually existed during the Umayyad Dynasty confers, in a sense, prophetic legitimacy upon peaceful coexistence in the region—at least in Bustros’ account.

The theme of Muslim-Christian amity featured in the lives and actions of her story’s characters as well. The main antagonist, Yazid, is the son of a Christian woman (both historically and in the novel). In La Main d’Allah, he warmly recalls moments of his childhood spent in a church and poetically compares Oraïnab to a beautiful “golden haloed” (Christian) icon he had admired in his childhood (84). Indeed, one of Yazid’s few redeeming qualities in the novel is his friendship and kindness towards Christians. Among other things, Bustros’ Yazid hires a Christian monk to tutor his son and invites the man to a grand celebration at his palace (90–92). Yazid’s primary wine-supplier, Akhtal, is also a Christian. Perhaps most significantly, when Abu Dardaa suggests that Yazid and Mu’awiya are too tolerant of Christians, Abu Huraya (another companion of the Prophet’s) defends Christians, noting the importance of strategic tribal alliances with Christians and the fact that many of them had supported the Muslim army in the past (74–75).

While it is hard to miss the peaceful encounters between Christians and Muslims in La Main d’Allah, Bustros ensured that no one would miss the subtext by including a pointed dedication at the beginning of her novel:

To my dear and luminous country [pays]

Chronicles

Of a time where the Islamic and Christian flags

Fraternized (v).51

The pertinence of Bustros’ interfaith message was not lost on her readers either. For example, her adoring fan, Lebnan, wrote:

May the Syrians of our days seriously meditate on the lessons of history and refer to this distant era of our grand ancestors, who you describe in a language so simply and knowledgeably, when Christians and Muslims [lived] under the same dome even while we were so close to the time of the Prophet and the birth of Islam.52

Regardless of the outcome of the Syrian Revolt or the final disposition of political borders in the Levant, Bustros’ La Main d’Allah presents a Syro-Lebanese vision of a community where both geographic and social boundaries are happily blurred in a comfortable peace, only disturbed at the end of the book by Mu’awiya’s political ambitions and Yazid’s carnal desires.

MULTIPLE STATES, ONE HOMELAND

As the 1920s wore on, battle lines sharpened between those who supported “Syrian unity”—that is the creation of a single Syrian state or federation that would include all of present-day Syria as well as Lebanon and the Sanjak of Alexandretta—and those who believed that Lebanon should remain politically separate and independent from Syria. The promulgation of the Lebanese constitution in 1926 (drafted with the help of Bustros’ friend Michel Chiha) affirmed Lebanon’s borders and its independence from Syria but failed to stifle opposition from Syrian unionists, who supported and, in some cases, participated in the Syrian Revolt. Amidst the tumult, Bustros’ personal social network became a microcosm of the rising sectarian and nationalist tensions when her brother, Michel Tueni, accused her Druze friend, Shakib Arslan, of threatening to kill Syrian Christians if they continued to “plot” against Syrian independence. The popular Maronite-led diaspora newspapers al-Hoda and Achaab (al-Sha’b) published similar charges. In a letter to Bustros, Arslan denounced the accusations as outrageous slander and asked for her help in clearing his reputation. He concluded by asking Bustros to thank his “old friend Michel” whom he said he had always liked and, in a nod to her novel, prayed that she would “be embraced by the hand—the hand of God [La Main d’Allah].”53

This exchange began an ongoing dialogue between Bustros and Arslan, spanning 1927–1928. Through a series of letters, the pair discussed and debated the nature of the French Mandate in Syria and what they each hoped to see for the region. In his letters, Arslan indicates support for an autonomous Mount Lebanon, which he called “l’ancien Liban” (or the old Lebanon), but he opposed the French-drawn borders of “Le Grand Liban,” which attached littoral cities like Tripoli, Beirut, Sur, and Saida to the Mutasarrifiyya of Mount Lebanon.54 In an apparent response to Bustros defending the French, Arslan said that France should be an ally of Syria, but not a tutor. He repeatedly insisted—in French, no less—that Syria would benefit from maintaining close ties with France. He also accepted the League of Nations system, generally. But he believed that Syria should be granted full independence from France and that French troops should be withdrawn.55 The fullest expression of the views Arslan expressed to Bustros, however, were captured in an undated letter written in Arabic. In it, he pointed to centuries of peaceful coexistence between Muslims and Christians in the region and argued that Christians would not have to fear persecution in an independent Syrian federation. He added that Syria wished to join the League of Nations, which was comprised mostly of Christian nations, and that it would thus be bound by the requirement that its members protect the rights of minorities.56

Unfortunately, Bustros’ responses to Arslan were not preserved, but in 1929, she responded publicly (albeit without invoking her friend by name) with a short publication entitled “Fredons.”57 No doubt drawing on the rich theatrical tradition of fin de siècle Egypt and the Levant, the text was presented as a dialogue or a play.58 It is a fictionalized conversation between two friends, a Lebanese Christian named Maroun and a Syrian Muslim named Mohammad, who reconnect in Egypt shortly after the death of famed journalist Ya’qub Sarruf (1852–1927), an Orthodox Christian who moved from Beirut to Cairo to participate in the city’s flourishing literary scene.59 The pair begin by discussing the importance of Dr. Sarruf’s legacy (Bustros, in fact, dedicated “Fredons” to this late man of “science and letters”) and trade pleasantries about the importance of enlightenment. Mohammad recalls spending time in Syria as a child and portrays Syria as a space where Christians, Muslims, and Jews could pursue enlightenment together, while Maroun bitterly replies: “Alas! So would my Lebanon, if it could” (“Fredons,” 345).

The conversation quickly turns to the cause of social discord in the Levant, with Mohammad and Maroun each rehearsing typical arguments offered by Syrian and Lebanese nationalists. Mohammad blames French colonialism and the creation of the Lebanese Republic, asking Maroun, “What has your Lebanon achieved so far?” Instead, he calls for national unity and “patriotic love” that respects all religions, telling Maroun that this has worked in Egypt. In a particularly cutting remark, Mohammad says that “the Lebanese don’t love their Lebanon” (347). Defending his sense of patriotism, Maroun invokes an affective, cross-border connection to the Levant and its natural landscapes as Bustros had done in La Main d’Allah. Syria and Lebanon depend on one another and are drawn together by the natural world, he claims. According to Maroun, Lebanon relies on the fertile Syrian plain, while the Lebanese mountain provides freshness to Syria. Historically, Mount Lebanon also protected the Syrian interior from invaders, allowing its culture to flourish. In short, the region’s terroir and its inhabitants were connected. But despite those “many attractions,” Maroun argues that there are obstacles to peaceful coexistence that necessitate a political separation: namely, sectarian violence (348).

“Fredons” then turns to different diagnoses of sectarianism. Maroun blames Syrian and Islamic “fanaticism” and claims that calls for Syrian unity were simply “masks.” “National unity,” he complains, is “poisoned honey that excites peoples of the interior.” He tells Mohammad that “Arab brigandage and fanaticism, under the pretext of union, will never enslave my Lebanon!” (355). Mohammad, by contrast, blames the violence on French colonial rule and the partition of Bilad al-Sham (Greater Syria). In his telling, French favoritism toward Lebanon fomented animosity among Syrians and was stifling patriotism and the development of humanism in Greater Syria (348–50, 355–56). The pair also discuss the French partition of Ottoman Syria. Maroun defends partition as a necessary and logical move made “in anticipation of revolts similar to those in the Mountain” (349). Mohammad rejects partition, noting that the French did not partition their own state when they faced episodes of civil strife in the past and suggesting that it only served to reinforce France’s colonial interests (349–50).

The debate ends inconclusively, with neither man convincing the other. Bustros concludes the exchange with a parting quip from Maroun that appears to have captured her own views as a Lebanese nationalist who nonetheless enjoyed friendships with Syrian Muslims: “Islam such as you evoke it would capture many hearts. . . [T]he day when Syria multiplies men in your image, Mohammad, Lebanon will descend from its pedestal and embrace unity” (357). However, in the meantime, Bustros continued to envision a single homeland with multiple states. Strikingly, this hybridity cropped up even when she was not writing for a public audience. For example, in the same year “Fredons” was published, Bustros briefly returned to the Levant for a visit. In her personal journal she described being overcome with emotion as the ship pulled into the port, writing “Syrie Liban, est-ce vous?”60 She had, indeed, arrived in Beirut—the capital of Lebanon, but also, perhaps in some senses, still part of Syria.

EMBODYING HOME IN BEIRUT AND AT THE WORLD’S FAIR

Repatriation is an important but often under-appreciated aspect of Syro-Lebanese migration. Although concrete statistics are hard to come by, scholars have estimated that as many as 25–45 percent of people who emigrated from Ottoman Syria in the early twentieth century returned during the interwar period. According to historian Stacy Fahrenthold, when they returned, “they brought the mahjar [back] with them.”61 In 1931, Bustros joined the ranks of repatriates, returning to Beirut to pursue a range of cultural, social, and political activities in her homeland. Here, I argue, she further developed her nostalgic nationalism and affective ties to a Syro-Lebanese homeland born in diaspora through new avenues.

Some of Bustros’ work dealt with Lebanon, specifically, such as the Salon de Peinture Libanaise, which she co-founded to promote Lebanese artwork.62 But she also remained interested in maintaining connections to the Syrian interior, turning affect into something tangible—even tactile—by joining an organization called Jam’iyya al-Nahda al-Nisa’iyya (The Women’s Renaissance Society). The society was founded in 1924 by Salma Sayigh (another Beirut-born Orthodox woman who had lived in Brazil for several years) and other leading women’s rights advocates. One of the society’s early goals was to promote local textile manufacturing and artisanal crafts produced by women.63 As part of her work with the Women’s Renaissance Society, Bustros opened a store called Syriban which showcased products made in Syria and Lebanon, encouraging people to buy them instead of foreign imports.64

Bustros’ work with the Women’s Renaissance Society operated on two levels. First, it aimed to resuscitate the region’s weaving and tapestry industries, which had employed women for generations and had been in sharp decline since World War I due to foreign competition.65 By getting involved in the often male-dominated distribution and marketing side of the industry, the Women’s Renaissance Society also flipped the gendered script, so to speak. Bustros recalled, with great amusement, one of the society’s trips to a Syrian market to discuss a business matter with male manufacturers “unaccustomed to discussing matters with women of the world.” 66 Eventually the men agreed to partner with the society to boost the sales and distribution of their goods. During a time when some schools prioritized teaching girls home economics—relegating them to the domestic sphere—and other women sought new “professional” careers as teachers or doctors, Bustros sought to bring an Ottoman past into the global capitalist markets of interwar era in a way that would materially benefit women.67

Second, the efforts of the Women’s Renaissance Society forged—or, perhaps more appropriately, reified—an economic connection between Lebanon and Syria despite nation-state borders that only continued to ossify in the 1930s. This was not only reflected in the name Syriban but also in how the store operated. Bustros explicitly cast her enterprise as one that transcended borders, telling an audience that in Syriban, “glasswork from Damascus rubbed shoulders with silks [and] tapestries from Zouk [in Mount Lebanon].”68 After Lebanon’s independence from France, Bustros would build on this work and continue her outreach to rural communities—especially rural women.69

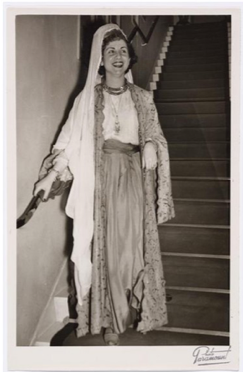

In the course of her work with Syriban, Bustros became increasingly interested in traditional outfits from Bilad al-Sham and began researching Ottoman-era fashion.70 Her connections to the textile industry allowed her to commission actual costumes, which she then invited guests to wear at her palatial estate in Beirut. Such gatherings were common during the interwar period, fitting well within what has been called the “grand ball era of bourgeois society” in Beirut.71 However, while most balls featured partygoers in predominantly Western or European-style attire, at Bustros’ home (Image 1), upper-middle-class, urban, cosmopolitan women and men donned garments seldom seen in the Levant after the mid-nineteenth century, including the ṭanṭūr (a bridal headdress) and shirwāl (baggy trousers), as well as garments more commonly seen in the Arabian Peninsula or in rural communities like the kūfiyya (male headscarf).72

Attendees of these events represented a veritable Who’s Who of Beirut’s old Christian elite, including members of the Sursock, Pharaon, Trad, Debbas, Tabet, Eddé, and Bustros families. European visitors to the city were frequently invited as well. A reporter for the local Francophone outlet L’Orient described one event as “an enchantment for the eyes,” and “a picturesque spectacle” with “sumptuous or ravishing female costumes.”73

Bustros’ costume parties reflected a tension between attachments to elite cosmopolitan experiences—especially in diaspora—and to the homeland. According to photographer Gregory Buchakjian, Beirut’s interwar evening balls were often photographed and publicized as a way for the “Beiruti bourgeoisie [to assert] itself as the dominant class, as it simultaneously claimed to represent the whole country.”74 Thus, claims to cultural authenticity were essential—in fact, at a 1938 soirée that Bustros and the Women’s Renaissance Society hosted at Le Restaurant Français in Beirut, prizes were awarded for the most “authentic” costumes.75 These performances represented a kind of bourgeois nostalgia for an inherited, “traditional” Ottoman past while also embodying an affective self-identification with reinvented customs, costumes, and traditions.76 At the same time, by borrowing from Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine, the elaborate outfits pointed to a transcendent Levantine cultural heritage, despite the political commitments of Bustros and her friends to the Lebanese state, as such. In effect, she translated a vision of homeland first imagined in her diasporic literature into Beirut’s material culture.

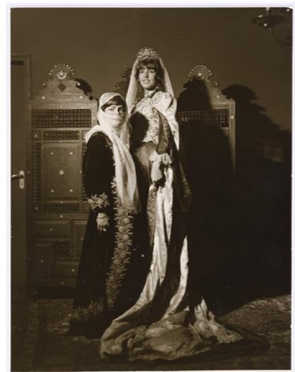

The following year, Bustros brought her imagined homeland back to the mahjar when she was invited to help organize the Lebanese pavilion at the 1939–1940 World’s Fair in New York City. Building on her lavish Beiruti costume parties, Bustros designed and commissioned several “costumes orientaux” (her term) and had friends and relatives model them and pose for a photo studio in Beirut (Images 2–4) before they were put on display in the United States.

As always, Bustros was mindful of her audience and wanted to ensure that her vision would be clearly understood. Her thinking behind the costumes was most clearly captured in a series of watercolors painted by her friend Georges Cyr (1881–1964), a French-born artist who later emigrated permanently to Beirut in 1934.77 Bustros captioned the portraits and composed a poem to introduce them. The collection was then compiled and printed by the Catholic Press in Beirut for distribution during the opening of the World’s Fair. The volume made it possible for those in Syria and Lebanon who could not travel to the United States or attend one of Bustros’ parties to also see her artistic rendering of the Levant. Consistent with her earlier literary and philanthropic work, Bustros waxed nostalgic for a precolonial past where geographic boundaries were blurred and diverse communities coexisted peacefully as part of a shared homeland.

Despite being designed for the Lebanese pavilion at the World’s Fair, the captions on Bustros’ costumes capture a bold geographic sweep of Bilad al-Sham, with figures from the cities and towns of Beirut, Tripoli, Damascus, Homs, and Hasbaya; the villages of Qartaba, al-Mishrifa, Zaydal, and Fayruza; and several rural areas including ‘Akkar, the Jabal Druze, the Hawran, and the Orontes Valley. Bustros’ accompanying poem includes parts of historic Palestine as well. While there are subtle regional differences in the costumes, the overall aesthetic is remarkably similar: bright colors, flowing garments, and idyllic scenery all conjure up a shared cultural heritage.78

The poem that Bustros composed for the collection articulates a shared cultural heritage deeply rooted in ancient history. Describing her costumes, she writes:

They outline the tracks of a history which aspires to last.

They affirm the ancient influence of the sumptuous rustic garb,

Of the long-plaited hair of Djebel lads, and of the tall sugarloaf felt hats of our peasants.

A heritage from Cana, Palmyra, Galilee, and the Phoenician cities which catered to monarchs.

These pictures sing the quaint charm of Lebanese seasons.79

Like most nationalists, she borrowed from a glorified past to celebrate a people in the present. But she also strayed beyond the territorial boundaries of the Lebanese Republic, dipping into ancient cities in Syria and Palestine. As before, doing so did not mean that she wanted to alter Lebanon’s borders. By 1939, even Syria’s elite nationalists had largely accepted that Lebanon would never be part of a Syrian federation.80 Rather, by transcending the borders of French partition in service of an explicitly Lebanese nationalism, Bustros asserts an inexorable and, indeed, vital connection between Lebanon and the rest of Bilad al-Sham.

The costumes orientaux conveyed Bustros’ vision of the social order as well, particularly regarding religious coexistence and the status of women in the region. Like her depictions of religious communities in La Main d’Allah, Bustros’ ecumenicalism is subtle but present as she showcases a diverse religious mosaic. For example, in the collection of watercolors, Alawis and Druze are identified as such, reminding her global audience of Lebanon’s diversity. The paintings also weave Christianity and Islam into the landscape, depicting a church—complete with a cross, a belfry, and a black-robed, bearded priest—and a mosque, with a prominent minaret and a friendly Lebanese sheikh. Notably, both the church and the mosque are contained within the territorial boundaries of Lebanon, gently challenging the notion of Lebanon as a Christian republic. The religious identities of most figures, however, are ambiguous. Is a given person a Muslim or a Christian? Does it matter?81

The costumes and portraits also reflect Bustros’ broader commitments to the advancement of women in society. The women in the paintings illustrate many ways of being a woman from Bilad al-Sham—none of them weak or servile. Two women—a Druze and a Syrian Bedouin—are depicted as mothers caring for children, a few are portrayed engaging in some form of leisure, and several are performing tasks such as carrying water or food. Most strikingly, only one woman is pictured with her husband; the rest stand by themselves or with other women as fully actualized subjects presented on their own terms in a way that likely would have come as a surprise to visitors of the World’s Fair.82 For Bustros, however, the advancement of women in society was simply in keeping with her homeland’s history and heritage. In her poem, she writes:

Oh! Women of my country, when at sunsets your garments stand out in the light of October and its breeze as you tread along the lane leading to the fountain.

They are the strange perfume which you exhale into the cool evening air, beloved Lebanese soil…

I am but a scribe inspired by the god of reminiscence.83

As with her diasporic writings, Bustros’ Syriban, her work with the Women’s Renaissance Society, and her costumes orientaux reconciled nostalgia for the pre-partition Ottoman past she had been born into with the new political framework she stepped into upon her return to Beirut.

CONCLUSION

Taken on its own terms, Eveline Bustros’ literary, artistic, and activist work during the interwar period defies easy categorization. In the broader context of diaspora studies, it is easy to overlook. In one sense, she was a migrant—part of the expansive Syro-Lebanese mahjar—who spent over a decade in Paris and a few years in Egypt. However, she ultimately repatriated and went on to have a storied career in her home city. If we conceive of migration as a singular, unidirectional event, focusing only on what happens away from one’s homeland, then Bustros’ mahjar story ends in 1931. However, it is clear that her thinking, writing, and work back in the Levant was inexorably shaped by her experiences abroad—and, indeed, it continued to be shaped by her participation in countless international organizations and conferences aimed at articulating and advancing women’s causes around the world.84 Thus, Bustros’ story urges scholars to understand migration as a multidirectional phenomenon of movement and exchange. Doing so allows us to see the development of ideas, ideologies, and identities through migration and mobility as a dialectical process.

Bustros’ conception of national identity and the mediums through which she imagined her homeland were also not as clear as those of many of her contemporaries—at least not at an initial glance. In the midst of sharpening boundaries along national and religious lines, Bustros sought to transcend divisions and blur boundaries in her rapidly changing homeland. She was resolute in her commitment to Lebanese nationalism and supported the French partition of its Syrian and Lebanese Mandate, but she still felt a deep connection toward Ottoman Syria. Both as an émigré writer in Paris and in her later work in Beirut, Bustros asserted cultural claims and even economic ties to the Syrian interior. Hers was not a nationalism of maps and bounded territory, but of affect and nostalgia. In an era where so many men wrote petitions and manifestos spelling out their aims and opinions in starkly clear terms, sources like historical novels, fictionalized dialogues, poems, bourgeois fashion shows, and watercolor paintings can fall by the wayside. Yet they offer crucial insights into the nuance and complexity of intersectional identities in the mashriq and mahjar.

NOTES

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewer and the entire editorial team at Mashriq & Mahjar for their helpful comments, suggestions, and edits. I would also like to thank Stacy Fahrenthold, Akram Khater, and Andrew Arsan for organizing the Khayrallah Center’s “New Perspectives on Middle East Migrations” workshop, out of which this article originated. I am particularly grateful for feedback and suggestions from Camila Pastor, Ghenwa Hayek, Joseph Leidy, Diogo Bercito, Lauren Banko, and others who pushed me to think in new and productive ways. Finally, I am deeply indebted to the Bustros-Sehnaoui family for preserving Eveline’s personal papers and photographs and for making them publicly available at the American University of Beirut and the Arab Image Foundation, respectively.↩︎

A note on transliteration: As a general principle, I defer to the transliterations that mahjari writers employed themselves when writing in the Latin alphabet (e.g., Eveline Bustros and Hector Klat). When discussing purely fictional characters in Bustros’ writing (e.g., Maroun in “Fredons” and Oraïnab in La Main d’Allah), I similarly preserved Bustros’ spelling. However, when discussing the historical figures in Bustros’ work, I relied on the IJMES system—omitting diacritical marks in proper names for ease—rather than her French-style transliterations (e.g., Caliph Mu’awiya rather than Bustros’ Calife Moawia) because the former comports with most Anglophone scholarship on this period in history.↩︎

Eveline Bustros, “Fredons,” (Beirut, 1929), republished in Bustros, Romans et Écrits Divers [Novels and Assorted Writings] (Beirut: Éditions Dar An-Nahar, 1988), 348. Text references are to the 1988 edition. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are mine.↩︎

Akram Fouad Khater, Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870–1920 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 1–8; Kemal H. Karpat, “The Ottoman Emigration to America, 1860–1914,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 17, no. 2 (1985): 175–209; Will Hanley, “What Ottoman Nationality Was and Was Not,” in The Subjects of Ottoman International Law, eds. Lâle Can, Michael Christopher Low, Kent F. Schull, and Robert Zens (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2020), 61–74; Stacy D. Fahrenthold, “‘Claimed by Turkey as Subjects’: Ottoman Migrants, Foreign Passports, and Syrian Nationality in the Americas, 1915–1925,” in Can et al., Subjects of Ottoman International Law, 216–36.↩︎

Carol Hakim, The Origins of the Lebanese National Ideal: 1840–1920 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 214–23; Stacy D. Fahrenthold, Between Ottomans and the Entente: The First World War in the Syrian and Lebanese Diaspora, 1908–1925 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 85–112.↩︎

Elizabeth F. Thompson, How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs: The Syrian Arab Congress of 1920 and the Destruction of Its Historical Liberal-Islamic Alliance (New York: First Grove Atlantic, 2020), 3–20, 59–104.↩︎

Andrew Arsan, “The Patriarch, the Amir, and the Patriots: Civilisation and Self-Determination at the Paris Peace Conference,” in The First World War and Its Aftermath: The Shaping of the Middle East, ed. T. G. Fraser (London: Gingko Library, 2015), 140–45.↩︎

Michael Goebel, Anti-Imperial Metropolis: Interwar Paris and the Seeds of Third World Nationalism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015).↩︎

Various correspondence between Shakib Arslan and Eveline Bustros, A: 305.4.1, box 3, file 6, Evelyne Bustros Collection, 1878–1971, American University of Beirut Library Archives (hereafter EB Papers). For more on Arslan, specifically, see William L. Cleveland, Islam Against the West: Shakib Arslan and the Campaign for Islamic Nationalism (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985); and Reem Bailony, Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925–1927 (PhD diss., University of California Los Angeles, 2015).↩︎

Georges Catroux to Eveline Bustros, 2 June 1927, box 3, file 5, EB Papers. Regrettably, Bustros’ correspondence to Catroux was not preserved.↩︎

Nicolas de Bustros, Je Me Souviens (Beirut: N. de Bustros, 1983), 14–16, 26–34; Samir Kassir, Beirut, trans. M. B. DeBevoise (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 304–26.↩︎

Sarah M. A. Gualtieri, Arab Routes: Pathways to Syrian California (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2020), 79–83, 95–109; Stacy D. Fahrenthold, “Ladies Aid as Labor History: Working Class Formation in the Mahjar,” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 17, no. 3 (Nov. 2021): 326–47; Lily Pearl Balloffet, “From the Pampa to the Mashriq: Arab-Argentine Philanthropy Networks,” Mashriq & Mahjar 4, no. 1 (2017): 5–30; Brinda J. Mehta, “The Painful Road to Freedom in Maram al-Masri’s Elle Va Nue la Liberté (Freedom Walks Naked),” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 18, no. 2 (July 2022): 264–76, 281; Maria Holt, “Stories of Identity and Resistance: Palestinian Women outside the Homeland,” in Diasporas of the Modern Middle East: Contextualising Community, eds. Anthony Gorman and Sossie Kasbarian (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), 212–38; Tasnim Qutait, Nostalgia in Anglophone Arab Literature: Nationalism, Identity, and Diaspora (London: I.B. Tauris, 2021).↩︎

Fahrenthold, Between the Ottomans and the Entente, 85–112.↩︎

“Treaty of Peace with Turkey, Signed at Lausanne, July 24, 1923,” in The Treaties of Peace, 1919–1923, ed. Lawrence Martin, vol. 2 (New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1924). On the messiness and even violence resulting from these new interwar citizenship regimes, see, inter alia, Lauren Banko, The Invention of Palestinian Citizenship, 1918–1947 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 84–112; Sarah Shields, “The Greek-Turkish Population Exchange: Internationally Administered Ethnic Cleansing,” Middle East Report, no. 267 (Summer 2013): 2–6, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24426444; and Aslı Iğsız, Humanism in Ruins: Entangled Legacies of the Greek-Turkish Population Exchange (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).↩︎

Letter to Aristide Briand, 9 September [192]6, 132PO/3/169 – Buenos Aires: Ambassade, Centre des Affaires Diplomatiques de Nantes. The letter referred to Syrians and Lebanese in South America.↩︎

Other examples include literary societies like New York City’s al-Rābiṭa al-Qalamiyya (The Pen League, est. 1920) and São Paulo’s al-‘Uṣba al-Andalusiyya (The Andalusian League, est. ca. 1934). Some Syro-Lebanese charitable organizations have persisted into the twenty-first century. See Lily Pearl Balloffet, Argentina in the Global Middle East (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2020), 172–84.↩︎

Simon Payaslian, “Imagining Armenia,” in The Call of the Homeland: Diaspora Nationalisms, Past and Present, eds. Allon Gal, Athena S. Leoussi, and Anthony D. Smith (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 124.↩︎

Payaslian, “Imagining Armenia,” 108; see also Jacob M. Landau, “Diaspora Nationalism: The Turkish Case,” in Gal et al., The Call of the Homeland, 219–40; and Kim D. Butler, “Defining Diaspora, Refining a Discourse,” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 10, no. 2 (Fall 2001): 216.↩︎

On migrant narratives challenging methodological nationalism, generally, see Anna Amelia, Devrimsel D. Nergiz, Thomas Faist, and Nina Glick Schiller, eds., Beyond Methodological Nationalism: Research Methodologies for Cross-Border Studies (New York: Routledge, 2012).↩︎

Occasionally, Bustros included Arabic words or phrases. For an analysis of these linguistic slippages in her later work, see Michelle Hartman, Native Tongue, Stranger Talk: The Arabic and French Literary Landscapes of Lebanon (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2014), 82–104.↩︎

I borrow from Salman Rushdie, Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981–1991 (London: Granta Books, 1991), 10. On other “mode[s] of diasporic nostalgia,” see Afsane Rezaei, “The Ritual Fusion: Individuality, Tradition, and Sensory Memory in Iranian Women’s Islamic Gatherings in Los Angeles,” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 18, no. 2 (July 2022): 216–37.↩︎

“Notice Bibliographique,” box 1, file 2, EB Papers; Untitled journal, 1 January 1899, box 1, file 1, EB Papers.↩︎

“Notice Bibliographique.” At the time, Egypt boasted a large and prolific Shuwami or Greater Syrian community. The classic account is Thomas Philipp, Syrians in Egypt, 1725–1975 (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1985).↩︎

Asher Kaufmann, Reviving Phoenicia: The Search for Identity in Lebanon (London: I. B. Tauris, 2004), 183–84, see also 67, 98, 195–96.↩︎

Kaufmann, Reviving Phoenicia.↩︎

“Notice Bibliographique.”↩︎

Maxime Weygand to Eveline Bustros, 14 July 1926, box 3, file 1, EB Papers; Henri Gouraud to Eveline Bustros, 4 July 1926, box 3, file 11, EB Papers; Georges Catroux to Eveline Bustros, 21 and 26 May 1927, box 3, file 5, EB Papers.↩︎

Maxime Weygand to Eveline Bustros; Hector Klat to Eveline Bustros, 10 April 1926, box 3, file 1, EB Papers; Shakib Arslan to Eveline Bustros, 6 August 1926, box 3, file 1, EB Papers.↩︎

On Phoenician poems and books, see Kaufmann, Reviving Phoenicia, 65–70.↩︎

G. R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2000), chaps. 3, 4; Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization, vol. 1, The Classical Age of Islam (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974), 217–23.↩︎

Thomas Philipp, Jurji Zaydan and the Foundations of Arab Nationalism (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2014).↩︎

Paul Souday, “Ancient Syria in a New French Novel,” New York Times, 29 August 1926.↩︎

Eveline Bustros, La Main d’Allah [The Hand of God], 2nd ed. (Paris: Éditions Boussard, 1926), 1–2. Text references are to this edition. Lammens’ historical account on this period is H. Lammens S. J., Le Califat de Yazid 1er (Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique, 1921). On her ties to Lammens, see Henri Lammens to Eveline Bustros, 1926–1927, box 3, file 4, EB Papers.↩︎

Ben Salam was also a fictional, but plausible, character as many Jews in Arabia did convert to Islam.↩︎

Elizabeth M. Holt, Fictitious Capital: Silk, Cotton, and the Rise of the Arabic Novel (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), 18–23, 27–31; Ami Ayalon, The Press in the Arab Middle East: A History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 31–36. I am grateful to Ghenwa Hayek for pointing me to al-Bustani’s work.↩︎

Stephen Sheehi, “The Love of a Woman and a Nation: Desire, Progress, and Reform in Salīm al-Bustānī’s al-Huyām fī Jinān al-Shām,” Canadian Review of Comparative Literature 37, no. 1–2 (2010): 127–36; Basilius Bardawi and Fruma Zachs, “Between ‘Adab al-Riḥlāt and ‘Geo-literature’: The Constructive Narrative Fiction of Salīm al-Bustānī,” Middle Eastern Literatures 10, no. 3 (Dec. 2007): 208–12.↩︎

Qutait, Nostalgia, 2.↩︎

B. Lebnan to Eveline Bustros, 1 November 1926, pp. 2–3, box 3, file 1, EB papers.↩︎

B. Lebnan to Eveline Bustros, p. 3.↩︎

B. Lebnan to Eveline Bustros, pp. 3–4.↩︎

On golden ages as coping mechanisms for contemporary challenges, see Qutait, Nostalgia, 33–88.↩︎

“Phoenician” entrepreneurship within Syro-Lebanese diaspora communities remained a key marker of identity well into the twentieth century. Alixa Naff, Becoming America: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985).↩︎

Souday, “Ancient Syria in a New French Novel.”↩︎

Paul Souday to Eveline Bustros, 19 February–5 August 1926, box 3, file 3, EB Papers.↩︎

Shakib Arslan to Eveline Bustros, 6 August 1926.↩︎

Ussama Makdisi, Age of Coexistence: The Ecumenical Frame and the Making of the Modern Arab World (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019), 218.↩︎

Michael Provence, The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005).↩︎

Reem Bailony, “Transnationalism and the Syrian Migrant Public: The Case of the 1925 Syrian Revolt,” Mashriq & Mahjar 1, no. 1 (2013): 8–29; Bailony, “From Mandate Borders to the Diaspora: Rashaya’s Transnational Suffering and the Making of Lebanon in 1925,” Arab Studies Journal 26, no. 2 (Fall 2018): 45–74.↩︎

Al-Mughira was an actual historical figure who served as Governor of Kufa under Mu’awiya until the former’s death in 671 CE. However, Bustros’ account of him is partially fictionalized: al-Mughira never resigned as governor of Kufa and was not a close advisor to Mu’awiya.↩︎

Bustros’ setting was historically accurate. After the Arab conquest of Damascus, the ancient cathedral was shared by Christians and Muslims, with the latter worshipping in a small muṣallā in the church. See Finbarr Barry Flood, The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Makings of an Umayyad Visual Culture (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 1–4. The church was later destroyed to make way for the Great Mosque of Damascus in the eighth century CE, but this occurred after the period in which La Main d’Allah was set.↩︎

The word “pays,” or “country,” is arguably ambiguous and likely extends beyond the borders of the Lebanese Republic.↩︎

B. Lebnan to Eveline Bustros, pp. 2–3.↩︎

Shakib Arslan to Eveline Bustros, 18 and 22 July 1927, box 3, file 6, EB Papers.↩︎

Shakib Arslan to Eveline Bustros, 18 July 1927.↩︎

Shakib Arslan to Eveline Bustros, 12 and 28 June 1927, box 3, file 6, EB Papers.↩︎

Shakib Arslan to Eveline Bustros, undated, box 3, file 6, EB Papers.↩︎

Arslan’s letter appears as pages 338–41.↩︎

This unusual style resembles Muhammad al-Muwaylihi’s Hadith ‘Isa Ibn Hisham, a popular collection of articles published in Misbah al-Mashriq from 1898–1902 and republished as a popular national textbook in 1927. It is unclear, however, whether Bustros drew inspiration from this. See Muḥammad al-Muwayliḥī’, What ‘Isā Ibn Hishām Told Us: Or, a Period of Time, ed. and trans. Roger Allen, 2 vols. (New York: New York University Press, 2018). On the theatrical tradition in the Eastern Mediterranean, see Ilham Khuri-Makdisi, The Eastern Mediterranean and the Making of Global Radicalism, 1860–1914 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 63–92.↩︎

Sarruf published al-Muqtataf with Faris Nimr. It was one of the most popular Arabic newspapers of its day. Khuri-Makdisi, The Eastern Mediterranean, 48–49.↩︎

Untitled journal, 1929, box 1, file 1, EB Papers.↩︎

Stacy D. Fahrenthold, “Return Migration and Repatriation: Myths and Realities in the Interwar Syrian Mahjar” in Routledge Handbook on Middle Eastern Diasporas, eds. Dalia Abdelhady and Ramy Aly (London: Routledge, 2022), 308–10. See also Khater, Inventing Home, 108–45.↩︎

“Notice Bibliographique.”↩︎

Anbara Salam Khalidi, Memoirs of an Early Arab Feminist: The Life and Activism of Anbara Salam Khalidi, trans. Tarif Khalidi (London: Pluto Press, 2013), 104; Elizabeth Thompson, Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal Privilege, and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 94–100.↩︎

Address by Bustros about “La Renaissance Feminine,” box 1, file 3, EB Papers. While undated, the address occurred sometime after the death of Salma Sayigh in 1953 because she is referred to as deceased.↩︎

On women in the agricultural side of the silk industry, see Beshara Doumani, Family Life in the Ottoman Mediterranean: A Social History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 224–74; on women in the production side of the textile industry, see Khater, Inventing Home, 19–47; on the textile industry generally, see Roger Owen, The Middle East in the World Economy, 1800–1914, 2nd ed. (London: I. B. Tauris, 2002), 261–66.↩︎

Address by Bustros about “La Renaissance Feminine.”↩︎

On home economics, see Ellen Fleischmann, “Lost in Translation: Home Economics and the Sidon Girls’ School of Lebanon, c. 1924–1932,” Social Sciences and Missions 23, no. 1 (2010): 32–62.↩︎

Address by Bustros about “La Renaissance Feminine.”↩︎

Nova Robinson, “Reaching Rural Women: The Village Welfare Society, Women’s Rights, and Development Discourse in Post-Independence Lebanon” (paper presentation, Middle East Studies Association Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, 14 November 2019).↩︎

“Notice Bibliographique.”↩︎

Gregory Buchakjian, “Beirut by Night: A Century of Nightlife Photography,” Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 8, no. 2–3 (2015): 257.↩︎

0257se00010 and 0257se00012, Nayla Bustros Sehnaoui Collection, Arab Image Foundation, Beirut. The photograph was likely taken in the 1930s, but the precise date is unknown. Compare, for example, Image 1 to photographs in Buchakjian, “Beirut by Night,” 263.↩︎

Marcelle Proux, “Le Bal des Costumes Régionaux Organisé par la ‘Renaissance Féminine’ S’est Déroulé Mercredi dans un Éclat Exceptionnel,” L’Orient 262 (29 May 1938).↩︎

Buchakjian, “Beirut by Night,” 260.↩︎

Proux, “Le Bal des Costumes.”↩︎

On bourgeois nostalgia in a positive light, see Salim Tamari, “Bourgeois Nostalgia and the Abandoned City,” in Mountain Against the Sea: Essays on Palestinian Society and Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 56–70.↩︎

L’Or Iman Puymartin, “Georges Cyr, Lebanon (1881–1964),” Dalloul Art Foundation, website, accessed 22 August 2022, https://dafbeirut.org/en/georges-cyr.↩︎

Eveline Bustros and Georges Cyr, Lebanese and Syrian Costumes [Costumes Orientaux] (Beirut: Imprimerie Catholic, 1939), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9107268h/f47.item#. In this copy, available online through the Bibliothèque Nationale Française, the poem was translated from French into English by an anonymous editor.↩︎

Bustros and Cyr, Lebanese and Syrian Costumes, n.p.↩︎

In 1936, the Syrian National Bloc effectively accepted a comprise: the smaller states of Damascus, Aleppo, Latakia, Jazira, and the Druze state would be united into a single Syrian federation. Lebanon and Alexandretta would be excluded. See Philip S. Khoury, Syria and the French Mandate: The Politics of Arab Nationalism, 1920–1945 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 456–71, 478–81.↩︎

Bustros and Cyr, n.p.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

For exciting new work on global feminism(s), see Bonnie G. Smith and Nova Robinson, eds., Routledge Global History of Feminism (New York: Routledge, 2022). For an overview of Bustros’ work specifically, see “Notice Bibliographique.”↩︎