Natalie El-Eid

VISUAL HAKAWATIS: DRAWING RESISTANCE IN LEILA ABDELRAZAQ’S BADDAWI AND MALAKA GHARIB’S I WAS THEIR AMERICAN DREAM

Abstract

In this paper, I explore how Leila Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi, published in 2015, and Malaka Ghraib’s I Was Their American Dream, published in 2019, work to forge a new space for the graphic novel in Arab American self-representation in twenty-first-century media, becoming emblematic of what I call “visual hakawatis.” Visual hakawatis use individualized acts of storytelling to transform fragments of their histories and memories into narratives of art and the written word that interconnect their personal, cultural, and historical experiences. In these convergences, works of resistance and refusal emerge, intervening in notions of history- and nation-making, national belonging, and national memory, resisting the marginalization or erasure of multiplicities of Arab American histories and identities within and beyond a US landscape. Some key questions informing my analysis include: How do Abdelrazaq’s and Gharib’s graphic novels reconceptualize historical as well as artistic conventions of storytelling in underscoring radical forms of witnessing, memory, and resistance to US hegemonic discourses and understandings of Arab Americans? In what ways does the visual medium of the graphic novel help Abdelrazaq and Gharib forge memories of and bear witness to inherited pasts and cultures, as well as underscore the complexity of Arab American positionalities and multiplicities today?

INTRODUCTION

The twenty-first century is an exciting time for witnessing the continuing expansion of media and themes within Arab American storytelling into the realm of visuality. The emerging genre of the graphic novel within transnational Arab literature exemplifies this expansion in ways that push the boundaries of conventional fiction, while simultaneously revisiting traditions of Arab oral storytelling by using the visual to underscore or even replace the verbal in these narratives. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, yet largely within the last decade, Arab American artists such as Iasmin Omar Ata, Toufic El Rassi, Sherine Hamdy, and Coleman Nye, as well as global Arab artists such as Lamia Zaidé, Riad Sattouf, and Zeina Abirached, have worked to collectively and increasingly forge a space for fiction and nonfiction graphic novels within transnational Arab literary traditions.1 With the recent flourishing of the transnational Arab graphic works in the twenty-first century, a new type of artist has thus evolved: the visual hakawati. Hakawati is the Arabic word for “storyteller.” Visual hakawatis, in my conception, use unique individualized acts of storytelling to construct transnational Arab histories and memories via marriages of art and the written word. In doing so, visual hakawatis interconnect personal, collective, and historical experiences to create complex works of contemporary resistance that intervene in notions of history- and nation-making, national belonging, and national memory.2

For the scope of this paper, I focus on Leila Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi, published in 2015, and Malaka Gharib’s I Was Their American Dream: A Graphic Memoir, published in 2019, vastly different but interconnected contemporary nonfiction graphic narrations of transnational Arab American identity and belonging written by children of immigrants living in the United States. While Abdelrazaq, in Baddawi, turns to her father’s history in Palestine and Lebanon to reclaim her roots and resist their erasure from her US standpoint, Gharib’s I Was Their American Dream turns to her parents’ immigration to the US and her own upbringing in America to resist the idea of any “authentic” and stable ethnicity, be it Arab, American, Filipino, or all of the above. I select these graphic novels for two primary reasons. First, Abdelrazaq and Gharib both piece together fragments of their memories and stories to reconstruct personal narratives that specifically speak to communal histories and conditions for contemporary transnational Arabs within the US landscape focused on in this paper. The term “Arab American” is capacious and contentious as it invokes notions of transnational (non)belonging. With these tensions behind this label in mind, part of the work this paper does in engaging authors who self-identify as Arab American is to both recognize and highlight that Arab Americans today can and do exist in an oft-invisibilized multiplicity of positionalities in connection to race, ethnicity, nation, and empire. As such, my examination of these two graphic novels also illuminates the ways in which Arab American artists such as Abdelrazaq and Gharib have worked to resist and negotiate these structural and systemic erasures on individual and communal levels, giving their identities, histories, and stories visibility over time via different and developing modes and mediums of storytelling. Next, as Abdelrazaq and Gharib both design and create their own visuals, these nonfiction graphic novels also serve as transgeographical and transtemporal contemporary works of self-representation, using illustration to illuminate what the written word cannot in telling the authors’ own histories. Abdelrazaq and Gharib, as visual hakawatis, thus converge the past and present, over “here” and over “there” to open new possibilities not just for expression, but for understanding the complex and multiple positionalities of transnational Arab Americans today. As I ultimately argue, radical stories of resistance and refusal emerge from these convergences, as Abdelrazaq and Gharib both use the medium of the graphic novel to reclaim belonging within a national landscape that has consistently and increasingly painted Arabs and Arab Americans as monolithic, threatening outsiders. In these culturally, politically, and socially significant texts, Abdelrazaq and Gharib therefore help forge novel spaces of self-representation in transnational Arab and American media, while visually and verbally bearing witness to sociopolitical and personal pasts invisibilized or misrepresented in the US media mainstream.

Literary scholars such as Shoshana Felman, Geoffrey Hartman, and Cathy Caruth have historically argued for the capacity of literature to bear witness to real-life events, connecting acts of testimony, fiction, and nonfiction, to the work of the imagination.3 These scholars have theorized literature as a way of knowing and telling, particularly of events often unimaginable and at times unspeakable. As Shoshana Felman contends in her groundbreaking work, Testimony, “It is precisely because history as holocaust proceeds from a failure to imagine, that it takes an imaginative medium [. . .] to gain an insight into its historical reality, as well as into the attested historicity of its unimaginability.”4 In expanding on what literary scholars have historically argued in terms of the capacity of literature to bear witness, I posit that graphic novels engage an even more heightened imaginative process of bearing witness as artists employ vastly complex and creative forms of the written word and illustration. Indeed, artists from marginalized populations in particular are increasingly turning to graphic novels as a mode of testifying to lived experiences of their communities within an increasingly violent and militaristic world.5 As scholar Hilary Chute notes in Why Comics?, comics become a form for bearing witness to war with the work of Keiji Nakazawa in Japan and Art Spiegelman in the US, both of whom were inspired by antiwar counterculture in their respective countries.6 In locating the roots of comics that bear witness within minority populations and antiwar counterculture, Chute opens the door for an examination of the graphic novels as a medium of resistance. However, she also importantly correlates war, violence, and militarism to the emergence and successive popularity of the comics medium, particularly in its capacity for witnessing and telling. This correlation, I argue, must be put into conversation with Arab and Arab American artists who, at the same time, are increasingly turning to the graphic novel medium as a mode of critical resistance to national and transnational landscapes that have consistently depicted their histories, identities, and homelands as violent and militaristic. In these contemporary works, there is an evolution of Arab storytelling that uses the visual in coalition with the verbal to serve not simply as creative works of entertainment but as critical forms of resistance.

VISUAL HAKAWATIS AND THE ART OF RESISTANCE

As renowned contemporary Arab American novelist Rabih Alameddine says of the historic Middle East, “Hakawatis were the primary form of entertainment. They could tell a story and expand it for about, you know, six months to a year.”7 The longstanding oral traditions of the Arab world have been preserved over centuries, as the Arab hakawati, according to scholars such as Barbara Romaine, is historically and contemporarily tasked with the critical role of “preserving the narratives essential to cultural survival.”8 The trope of the hakawati remains prominent in transnational Arab literature and cultural productions, as oral storytelling traditions of the Arab world have been taken up, reworked, and used as a point of connection between transnational Arab artists.9 Though conceptions of the hakawati across configurations of race, ethnicity, nation, gender, and sexuality continue to develop over time, in tracing the continued presence of the hakawati figure through the trajectory of transnational Arab works, it becomes evident that oral traditions of Arab storytelling have informed and inspired revisionary and radical forms of contemporary written narratives.10 In engaging the hakawati in an analysis of contemporary transnational Arab graphic artists, however, I explore the effects of the traditional hakawati performance beyond the verbal or written, into the realm of the visual. Aside from the riveting tales that they would recite (often from memory), hakawatis were also known for their grand bodily gestures and movements, as well as demonstrative facial expressions, adding an element of visuality to the power of their stories and the act of storytelling itself. With this knowledge, I redirect a common understanding of oral tradition that relies simply on the spoken word, arguing that the visual aspects of hakawati performance also serve as critical components of historical and contemporary Arab storytelling. The emerging medium of transnational Arab graphic novels thus intermingles the visual and the verbal in ways reminiscent of and in continuance with hakawati tradition, performance, and cultural significance.

Engaging in vastly different subject matters, Abdelrazaq’s and Gharib’s nonfiction projects are not only emblematic of the heterogeneity of the field of contemporary Arab American literature but also serve as forms of contemporary witnessing for Arab American memories and histories often marginalized within the US media landscape. These graphic novels thus function as anti-essentialized representations of Arab American identity, inherently connected in their resistance to hegemonic understandings of contemporary Arab American and US identity and belonging. Hegemonic understandings and misrepresentations of Arab identities in US political, social, and cultural discourses have a pronounced history in US media across genres.11 Orientalist tropes of Arabs are evident in US media as early as the nineteenth century, though the post-WWII literary movement in which Chute locates the emergence of the graphic novel as a mode of bearing witness also marked increasingly ominous misrepresentations of Arabs and Arab Americans in the West.12 These long histories of Arab American struggle, violence, and misrepresentation have again been brought to the fore by one of the most recent and prominent instances of war and violence between the US and the Arab world: the events of 9/11. My engagement of 9/11 here is not to suggest that 9/11 is a singular instance or moment of struggle and misrepresentation for Arab Americans; rather, I point to what Nadine Naber and Amaney Jamal call the shift in Arab and Arab American positionalities from “invisible citizens to visible subjects.”13 In its correlation with notions of increased visuality for Arab Americans, I place this shift alongside the emerging contemporary works of Arab American visual hakawatis, who employ the art of their works as well as heightened visibility of their very existences as modes of resistance. As Steven Salaita contends, “Before 9/11 scholars examined Arab American invisibility or marginality—or whatever other term they employed to denote peripherality—but after 9/11 they were faced with a demand to transmit or translate their culture to mainstream Americans.”14 Arab American graphic novels, remain an understudied mode of bearing witness, testimony, and what Salaita here calls “cultural translation” within a post-9/11 US media landscape. Though visual art media and the graphic novel genre have had a general uptick in the post-WWII era, in 9/11, Chute locates a milestone in the growth of the comic which also parallels the importance of the far-reaching sociopolitical contexts of the contemporary Arab American histories charted in Baddawi and I Was Their American Dream, as well the emergence of the transnational Arab graphic novel itself. As Chute posits, “The media spectacle of that day [9/11] ushered in a new, intensified global visual culture heavily invested in articulating—and often actually documenting—disaster and violence.”15 In dealing with the increased pressures and demand to, as Salaita claims, “translate” and “transmit” post-9/11, I find the evolution of the visual hakawatis, who use interconnected visual and verbal forms as a unique mode of self-expression and nonfiction testimony for Arab American artists increasingly faced with the need to render themselves legible within and beyond a US landscape. Even though the racialization of and violence against Arab American communities and individuals in the US well precedes 9/11, the national and collective trauma of this day plays a critical role in contemporary representations and racialization of Arab Americans, which have consistently painted Arabs and Arab Americans as monolithic racial “Others” who pose a tangible threat to US national security and thus have increasingly become representative of disaster and violence themselves. Both Baddawi and I Was Their American Dream, I contend, are forms of self-representation that highlight different but interconnected positionalities in terms of Arab American identity and experience post-9/11, within the newly intensified global visual culture Chute describes. Both graphic novels are transnational and revisionary in approach, problematizing and critiquing the binary of “here” versus “there” and “us” versus “them” dominant in US notions of belonging and citizenship, divisions that were reinscribed to many children of immigrants post-9/11, but particularly to Arab Americans, whose homelands were declared “at fault” for this act of terrorism on American soil. We can thus locate Leila Abdelrazaq’s and Malaka Gharib’s nonfiction graphic novels as working at this intersection of US national trauma and those of their original homelands, linking these fraught and traumatic histories both visually and verbally.

BADDAWI: (RE)CONSTRUCTING AND REMEMBERING TRANSNATIONAL ARAB AMERICAN HISTORIES

Though 9/11 was a critical moment for the growth of visual and verbal depictions of disaster and violence both in the US and around the world, it is also important to remember that for many Arab Americans, the violence of this day was not novel. Leila Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi, published in 2015, is a graphic novel that resists the erasure of such violence by visually and verbally reconstructing and remembering her ancestral past, beginning with her grandparents’ 1948 forced migration from Palestine to Lebanon.16 The majority of Abdelrazaq’s graphic novel is centered on her father, Ahmad, and his upbringing in a Lebanese refugee camp until the moment of his eventual immigration to the US. Branching from this individual history, Baddawi also works to make a claim that what happened in Palestine and to the Palestinians, the disaster17 and the violence, are not part of a historical Palestinian past. Indeed, they have widespread ramifications on millions of people all over the globe today.18 Abdelrazaq, a child of Arab immigrants living in post-9/11 US, is not removed from the war and violence that plagues both her ancestral history and that of her homeland. As the graphic novel works to bear witness to a history that, for Abdelrazaq, has been passed down from her father and must be remembered in order to resist its erasure, readers across the world are thus asked to bear witness to and remember this often silenced or misrepresented history as well. Described by Just World Books as the “first book-length graphic work written/drawn in English by a Palestinian”19 and shortlisted for the Palestine Book Awards in 2015, the production of the graphic novel itself forges a space within the genre for Arab Americans, particularly Palestinians, whose voices and testimonies are often invisibilized within and beyond US media culture.

Abdelrazaq’s narrative is centered on her father’s dislocation from Palestine and his upbringing in Lebanon, reconstructing an inherited history and memories, passed down by generation, that remain part of a collective, transnational past and present. Baddawi thus testifies to an individual and collective past in ways that promote remembrance, history remaking, and, accordingly, resistance to and refusal of erasure. What is remembered and retold, in this sense, may never die. Indeed, these retellings as evident in a graphic novel such as Baddawi are crucial to the survival of a nation and national consciousness that is often rendered invisible by a US mainstream. As scholar Juliane Hammer contends in Palestinians Born in Exile, concerning the role of historical national narratives in building national identity for younger generations of Palestinians:

The oral traditions, stories, and memories of the Palestinian past play a crucial role in educating them [younger generations of Palestinians], inside as well as outside Palestine. [. . .] For those Palestinians who were born and raised in exile, these memories are their connection to Palestine—their source of knowledge, attachment, and national identity.20

As Hammer notes, oral traditions, stories, and memories are integral in connecting the exiled peoples in particular to the homeland. Exile causes an increased reliance on memories and stories which work to engender this knowledge, attachment, and national identity across national borders. Through the work of remembrance, here in graphic novel form, connections can occur even when they are not experienced firsthand, as with Abdelrazaq, and even for those who cannot physically access the land, which is the case for many Palestinians today. Through its visual and written forms, Baddawi, as a reconstruction of a personal and communal Palestinian and Lebanese past from a US landscape, thus serves to foster this attachment, knowledge, and national identity across borders.

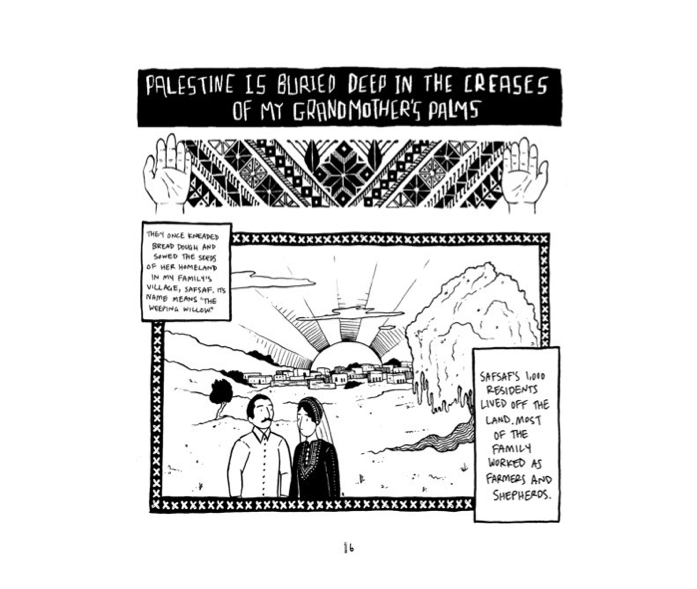

The introduction of Baddawi21 begins in Safsaf, Palestine, in a section titled, “Palestine Is Buried Deep in the Creases of My Grandmother’s Palms” (Baddawi, 16). Both the title and content of this section forge an immediate, resilient, generational connection between nation and individual, history and memory. The very next page of Abdelrazaq’s narrative speaks to the fracturing of this history and connection: the Safsaf massacre of 29 October 1948, which forced the narrator’s grandparents, and thousands of others, into life in a refugee camp in Lebanon named Baddawi. Baddawi is where Abdelrazaq’s father, Ahmad, was born.22 This introductory section therefore begins with the individual focus on Leila’s grandparents, shifts out to the national, the catastrophe of Palestine, and funnels back down to the individual through a return to a discussion of Leila’s father and his family. This fluctuation between the individual and the national from the very beginning of the text makes evident the interconnectedness between a national narrative, a familial history, and a transnational present, as Abdelrazaq begins to trace her roots by turning to a historical and ancestral past. Safsaf,23 as denoted by both the name of her father’s village and illustration of the weeping willow featured prominently on the narrative’s first page (Image 1), becomes an important written and visual symbol of the interconnected landscapes, memories, and histories that Abdelrazaq is mapping, and, thus, visually and verbally reclaiming.

Abdelrazaq’s introduction opens with an illustration of the narrator’s presumed grandparents against the backdrop of the tranquil-looking village of Safsaf, complete with a sun in the horizon and a large weeping willow with long, thick roots in the forefront. A text box reveals that “Safsaf’s 1,000 residents lived off the land. Most of the family worked as farmers and shepherds” (16). What follows this introduction is a three-part narrative marked by location and time period, starting with Ahmad in first grade at the Baddawi camp and ending with Ahmad’s eventual departure from Lebanon to attend college in the US. The graphic narrative closes with the illustration of a plane in the forefront flying away from the shore of Lebanon, drawn against a black background and the words, “He [Ahmad] would not return for ten years” (116). As the first visual and written words tell us, many Palestinians, like the narrator’s grandparents, were dependent on the land to live, literally and metaphorically rooted in Safsaf. As made evident in the graphic novel’s concluding visual and text, the loss of this land led to a diaspora that millions of people, and the generations that have come after them, are still contending with. Abdelrazaq, as a visual hakawati, uses the illustrations and words of her graphic novel to bear witness to this lost home, land, life, and disaster rendered invisible, one that largely informs her status as a Palestinian child of the diaspora in America today. As Abdelrazaq tells Herwees, “I just wanted to share those stories because they were stories that people outside of the Palestinian community didn’t necessarily hear very often. I was also using it as a way to inform people on the Palestinian refugee issue.”25

In the preface to Baddawi, Abdelrazaq writes, “Today, Palestinians make up the largest refugee population in the world, numbering more than five million. The Palestinian refugee community is made up of survivors of the mass ethnic cleansing, or Nakba, that forced us from our homeland in 1948, and the descendants of those survivors” (11; emphasis mine). The contemporary importance of Abdelrazaq’s narrative to not just her own life but a collective inherited history is also evident in the graphic novel’s dedication, which is not only “For my teta and jiddo”26 but also “for all those children of immigrants who have not forgotten their parents’ stories.” Therefore, Abdelrazaq’s graphic novel, while based in a past over “there,” is also for the children of immigrants living today over “here,” speaking to these individual and communal struggles with their identities and histories and bringing her own history to life in a work of resistance and refusal. As Abdelrazaq declares:

This story is about one individual, but its anecdotes are uttered in countless families, at children’s bedtimes, late at night. We stir the tales into our coffee with cardamom, and read our return in the grounds. That’s because, for Palestinians, preservation of the past is an act of resistance. It reminds us that we must continue to struggle, until liberation and return (12; emphasis mine).

This graphic novel then, for Abdelrazaq, functions as a marked act of resistance, particularly for Palestinians, who rely on these inherited traditions, such as cardamom with coffee and reading grounds, and memories, described here as bedtime anecdotes, to remain connected to the homeland. Preserving the past in this graphic novel entails bearing witness to it, in turn, refusing its erasure with words and visuals of reconstructed histories that should and must be remembered via these retellings. Storytelling becomes vital to this preservation, particularly via the graphic novel, which integrates the visual to further facilitate meaning and understanding of the memories Abdelrazaq has inherited and is passing on from the oral stories of her past. Indeed, Abdelrazaq closes her preface with the following line, “This book is a testament to the fact that we have not forgotten” (12), despite the graphic novel’s closing illustration of a plane headed for America’s borders, a nation in which stories like Ahmad’s are often rendered invisible or anti-nationalist.

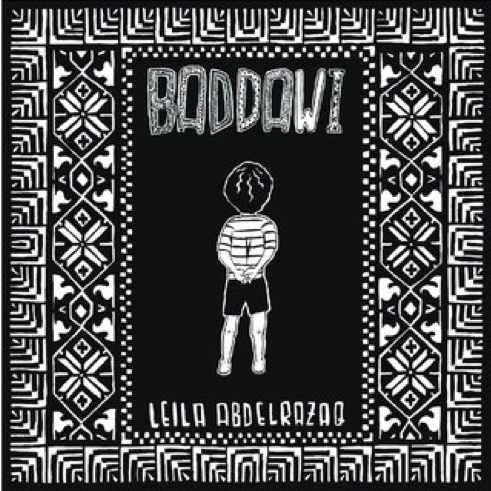

As the weeping willows of Safsaf’s widespread roots are visually and symbolically prominent in the text’s reconstructed history and remembrance, another illustration that denotes the visual resistance the graphic novel asserts is an allusion to the cartoon character created by Naji al-Ali27 in 1975: Handala.28 The graphic novel’s visual connection to Handala is evident from its cover, in which a cartoon child, presumably Abdelrazaq’s father, stands in replication of Handala’s stance, as he, too, bears witness to the tragedy unfolding in Palestine. The child drawn on the front cover, like Handala, is barefoot, with his back to the reader and arms clasped behind his back (Image 2). This child, however, contemporizes Handala through their clothing, shorts and a striped T-shirt, bringing a historical Palestinian struggle and resistance to a contemporary moment and people. As opposed to Handala’s short and sparse spikes of hair, this child has a full head of short dark hair. Though the child on the front cover dresses similarly to the way Ahmad does in the first part of Baddawi’s narrative, who this child is cannot be determined for certain. The title of the graphic novel, however, written directly above the child’s head, suggested that they are a baddawi, a faceless, rootless, stateless human being, bearing witness to disaster as they wait to go home. The cover of Baddawi thus forges an immediate visual connection to Palestinian history, culture, diaspora, and resistance.

As Abdelrazaq notes, Naji al-Ali “promised that once the Palestinian people were free and allowed to return home, Handala would grow up and the world would see his face” (11). As Palestinians today are still unable to return home, Handala has never turned around. Like the thousands of Palestinians Handala represents, we have not seen their faces. Baddawi attempts to tell us about these faces. As Abdelrazaq states,

The story you are about to read isn’t only about my father.

This story is about Handala. It is about my cousins and aunts and uncles. It is about those displaced multiple times, first from Palestine, then from countries like Kuwait and Syria. It is about five million people, born into a life of exile and persecution, indefinitely suspended in statelessness (11–12).

Moreover, it is about Abdelrazaq herself, an American-born child of the Palestinian diaspora living in post-9/11 US, visually and verbally refusing and resisting the erasure of her history through her graphic novel. In “Palestinian National Identity, Memory, and History,” Juliane Hammer quotes Palestinian American journalist Ali Abunimah, who wrote, in 1998, “Palestine exists because Palestinians have chosen to remember it. But memories fade and people die, and some are better at remembering than others. Memory is no longer enough. It is time to write history and time for each of us to become a historian.”30 In this sense, graphic novels such as Abdelrazaq’s become nonfiction testimonies to marginalized Arab American histories.

As visual hakawatis, Abdelrazaq and other Arab Americans using their graphic novels to refuse and resist invisibility also inscribe a place for the individual in both history, history-making, and nation-making. They not only remember the histories of their families and nations but use their art to illustrate and rewrite these personal and national histories, including a US history that has often excluded or erased them. In doing so, visual hakawatis become historians and storytellers, shedding light on what has historically been rendered invisible, and blurring the space between fiction and nonfiction. Drawing on Hobsbawm and Ranger,31 Hammer claims “A shared history or historical memory is one of the factors determining whether a group can be called a nation. This indicates that history is not a report on the past, but rather a set of fixed memories, collected, preserved, and transmitted by people and thus constructed or even ‘invented.’”32 As a visual hakawati, Abdelrazaq not only uses the graphic novel to creatively reconstruct her father’s memories and family’s history but she also becomes a historian who works to preserve the nation of Palestine itself, as seen in the fluctuation between the individual and the collective in both her narrative and preface. Through its written and visual reconstruction of an individual and communal marginalized history, Baddawi also serves as a way of nation-making for both Palestine and the US, resisting and challenging the idea that belonging in one national sphere, the US, is contingent upon erasing forms of belonging to other national spaces and contexts. As an American, Abdelrazaq’s text and history become emblematic of this hybridity; her present life as an American child of Palestinian immigrants in the US is not divorced from her ancestral history in Palestine. She remembers this past and asks readers to as well.

Another way in which Baddawi reinscribes a Palestinian national past via the visual is through pattern and design. In a thick border around the cover page is a traditional Palestinian tapestry of patterns and shapes in which Abdelrazaq is quite literally drawing a connection to Palestinian culture and tradition. These differing patterns, and their connections to Palestine, are evident are throughout the narrative; as Abdelrazaq makes sure to relay in her preface, “Throughout this book, you will see a variety of geometric, floral, and sometimes ‘pixelated’-looking patterns integrated into the illustrations. These patterns are designs typically used in tatreez, traditional Palestinian embroidery” (13). The traditional patterns illustrated in Baddawi thus work to root the reader into a sense of Palestinian tradition and history on each page they decorate. In these patterns, readers are literally and metaphorically framed within the beauty and diversity of these traditions, where they come from and where they travel, which is reinscribed throughout this transnational narrative.

Baddawi’s colors also work to heighten its message, as the graphic novel is written and drawn entirely in black and white. As McCloud contends, in terms of color, “In black and white, the ideas behind the art are communicated more directly. Meaning transcends form. Art approaches language.”33 Without employing color to relay certain emotions and meanings, Baddawi relies entirely on its words, shapes, and spaces to tell its story. Major sociopolitical events are brought to life throughout the narrative in disjointed figures and seas of black. Passages of time are marked throughout the narrative not just via the milestones of Ahmad’s personal life but by stark illustrations of the national/global war and violence that are shaping his movement through time and space. These interconnections and disjointed visuals are important to note, as they speak to the difficult ways in which Arabs must navigate their lives and the world, as well the ways in which they can/cannot understand both.

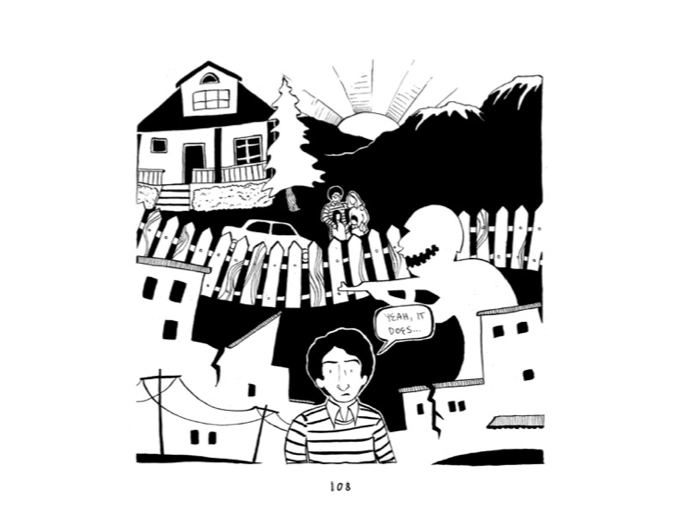

In the same way that Palestine and Lebanon are visually and verbally reconstructed in Baddawi, America also plays a critical role. This is perhaps most evident after Ahmad tells his friend Manal that he wants to go to college in the US. Manal replies by asking, “I mean, it just seems really far away, huh?” (107). The narrative then cuts to the next page. Across the middle of the page is a white picket fence (Image 3). Below the picket fence are large, white, fractured buildings juxtaposed against a black background. Electric poles and wires cut across the buildings. The largest shape beneath the picket fence is a faceless soldier, smiling and holding a gun. Above the dividing line of the fence is an illustration reminiscent of the opening visual of Palestine in the graphic novel’s introduction. The sun is on the horizon as a backdrop to the beauty of the home. However, this home is clearly an American one. There is no weeping willow, but instead a generic-looking oak tree adorns the front of this American yard. As opposed to the large, thick roots of the tree drawn in Safsaf, in this American Dream, the reader finds an illustration of a tree with no roots. A family, a man, dressed like Ahmad, a woman, and two children are standing together in the front yard, arms around one another, much like Ahmad’s grandparents stood together in front of Safsaf in the graphic novel’s introduction, before the Israeli invasion. Clearly an ideological representation of “the American Dream” juxtaposed with a violent representation of life and war in Palestine, this illustration is indicative of the ways the divide between Palestine and America is commonly inscribed by US nationalist ideologies. However, the explicit parallels literally and metaphorically drawn between this ideological representation of the American Dream and Palestine as illustrated on the graphic novel’s first page suggest these two nations are not as ideologically removed as one may imagine. Neither are the Arab Americans such as Abdelrazaq who embody and contend with cultures that are often visually and verbally portrayed as disparate within US hegemonic nationalist discourses.

The safety and security the American Dream can offer refugees is made apparent in the serenity of this illustration. At the end of the narrative, Ahmad chooses to immigrate to the US and pursue this dream rather than remain in Lebanon as a Palestinian refugee. Ahmad’s life in the US is not the focus of this narrative, what led him to America is; however, his American-born daughter is now retelling his past from her American present, one which Ahmad’s traumatic, diasporic, and marginalized past has informed and transformed. As Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi makes evident, these ancestral and national histories cannot be divorced from her present life in the US. Abdelrazaq’s graphic novel thus allows her to visually and verbally bear witness to a traumatic ancestral past in the Middle East, resisting its disconnection from both her present life and struggle as an Arab American, as well as the lives of other children of immigrants.

Like Abdelrazaq, Malaka Gharib’s graphic novel, I Was Their American Dream also bears witness to the personal and sociopolitical struggles of Arab American children of immigrants in the contemporary United States. As a visual and verbal construction of Gharib’s life as Filipino Arab American child of immigrants, Gharib, as visual hakawati, refuses and resists monolithic understandings of US national belonging, US national discourses on Arab Americans, and in particular, the erasure of complex and heterogenous Arab American identities. Where Baddawi uses its words, patterns, and colors to reconstruct and bear witness to a Palestinian national past often erased or misrepresented in a US landscape, I Was Their American Dream turns to the present-day US to interrogate the ways in which multiethnic American children of immigrants struggle with belonging and assimilation in a hegemonically white national culture and landscape.

I WAS THEIR AMERICAN DREAM: ARAB AMERICAN MULTIPLICITY AND THE (RE)MAKING OF AMERICA

I Was Their American Dream, a 2019 graphic memoir by Malaka Gharib, reconstructs her autobiographical history as an American child of two immigrants, a father from Egypt and a mother from the Philippines.35 The text charts the journey of Malaka’s life: from her parents’ respective immigrations to America and their marriage, to Malaka’s upbringing in the US, to Malaka’s own marriage to a white American man named Darren. Like Abdelrazaq, Gharib is the American daughter of immigrants. However, rather than focus on her father’s past in the Middle East and his eventual pursuit of the American Dream, Gharib’s contends with the allure and ideologies of America and Americanness in a graphic novel that testifies to her own life, primarily within the US. As Gharib, contending with notions of “Otherness” and misrepresentation in a US landscape, writes in her blog titled “Who Gets to Be American?”:

In the [American] news, people were saying that immigrants were coming into this country to steal jobs. That they were uneducated, poor, and desperate. Terrorists. Bad hombres [. . .] My immigrant parents didn’t fit the description. They were educated. Their families belonged to the middle class. And desperate? My mom never wanted to come to the States to begin with. Before she came here, she had a cushy job at a fancy hotel in Manila. But it wasn’t just my parents who were being misrepresented. It was also my whole world: me, my family, my upbringing.36

In her memoir I Was Their American Dream, Gharib resists pervasive media misrepresentations pertaining to national “Others” in the US by forging her own self-representation via the verbal and visual forms of the graphic novel. Throughout her graphic novel, Gharib bears witness to fragments of her own life to resist the assimilative pressures and erasures inherent in hegemonic understandings of national belonging for children of immigrants that are based on normative whiteness, assimilation, and financial success, while asserting a diverse and heterogenous (re)construction of America and Americanness not only for immigrants but also for their children.

The allure of America and the American Dream, for many immigrants, is the hope for a better life. This hope often carries over to the children of immigrants, whose parents just want their lives to be “better.” This is how Malaka’s story begins, as a child in in the US on the way to school with her mother, whose speech bubble reads “You have to be better than us” (American Dream, 6; author’s emphasis). Malaka’s unspoken response reads, “She never explained what she meant by that. But I understood” (7). This idea of betterment in terms of children of immigrants and their parents is a prominent theme in Arab American literature, taken up here by Gharib to set the foundation for the American Dream her parents had not just for themselves, but for her as well. America, for both Abdelrazaq’s father and Gharib’s parents, becomes associated with “better,” an idea both graphic novels engage and resist from their critical standpoints as American children of immigrants. Along with race, Gharib continuously navigates and reasserts the hybridized aspects of her identity from religion (her father is Muslim, her mother a devout Catholic), to language (English, Arabic, Tagalog), to food. On one page, Gharib both visually and verbally charts the social customs applicable/nonapplicable to each culture she embodies, such as eating with one’s hands or wearing slippers in the house. The negotiations between being Filipino, Egyptian, and American are the prevailing themes of the memoir, as Malaka’s complex self-representation of race and ethnicity complicates understandings of the seemingly disparate cultures that Malaka navigates and embodies.

In these negotiations of identity and culture throughout the text, Gharib critically bears witness to, resists, and refuses hegemonic and monolithic understandings of American and Arab American identities, as well as notions of betterment tied to the American Dream itself. At the beginning of the graphic novel, Malaka states, “I had to somehow rise above my parent’s life in America. But how? This is a story about that journey. And it starts before I was born” (8). In this turn to life before birth, as in Baddawi, we see an American present very much informed by a transnational past. As is the case with many American immigrants, including Leila’s father, Malaka’s mother was forced to leave the Philippines in the 1970s and immigrate to America to escape political disaster, violence, and trauma of her homeland. In turn, Malaka’s father, like Ahmad, left the Middle East to attend college in the US and pursue the American Dream.

For the Gharib family, the American Dream is first described and illustrated as:

A big house with a white picket fence! A two-car garage! Credit cards! Luxury handbags! Enough money to send back home to the parents! A Mercedes Benz or a Lexus! Annual trips to Disney World! Ralph Lauren polo shirts for the whole family! Kids that were American—but not too American! (22)

The American Dream in this passage is therefore constructed verbally and visually by the common notions of material goods, a private home, and financial success, all of which are linked to consumerism and capitalism as markers of American success and national belonging. However, the “not too American” reference here, linked to an illustration of Malaka herself, foreshadows Malaka and her parents’ ultimate refusal of complete assimilation to some qualifiers of a hegemonically white national culture and a resistance to the erasure of their diverse backgrounds. As Malaka recalls, “Twenty-five years later, my parents would tell me that being married to each other was the closest they ever got to the American Dream” (25). The American Dream as constructed above thus never came to fruition. Malaka’s parents eventually divorce, and her father gives up a pursuit of the American Dream to return to Egypt. However, this line suggests that the mixed-race marriage of Malaka’s parents, though it does not last, is perhaps the most important part of their respective immigrations. The American Dream is thus restructured here, as the material and hegemonic aspects of it are resisted and decentered in favor of a racial and ethnic diversity and multiplicity, which, in turn, we see throughout the graphic novel, including in Malaka’s own mixed-race marriage to a white man.

Gharib’s graphic novel as a whole works towards the development of a critical form of visual and verbal belonging that resists the assimilative pressures inherent in hegemonic understandings of the American Dream and national belonging. At the center of Gharib’s narrative is an ongoing attempt to bear witness to the negotiation of her own identity, one that speaks to many children of immigrants in the US today searching for an answer to the question: “What are you?” One page of the graphic novel, which is also excerpted on its back cover, highlights Malaka’s difficulty in answering this question (Image 4). Malaka, when asked by a Filipino peer, replies with a speech blurb saying:

In this passage, Malaka tries to navigate her identity in several ways. The first is via the Filipino family she grew up with right “here” in the US. The second is via the type of Filipino cultural foods she commonly eats. The third involves the school she went to, which is connected to the Catholic religion. However, this religious identification is quickly complicated by the declaration that her dad is Muslim and lives over “there,” in Egypt, which she visits often. The fourth is via the languages that Malaka is able to understand, and, to a certain degree, speak, asking, “How are you?” in both Egyptian and Tagalog. Malaka then concludes with the notion that she is both Egyptian and Filipino, before negating this conclusion by declaring she must be more Filipino because she spends more time with the Filipino side of her family. Therefore, in this passage, readers see Malaka struggling with, reconsidering, but ultimately working within and maintaining a binary of identity and labels within a US landscape.

However, by the end of text, “what” Malaka is, “mastering” a language or a culture, the labels she is given and gives herself, are visually and verbally resisted. In the last pages of the memoir, Malaka and her husband, Darren, are visiting Malaka’s father in Egypt. As they are drawn cruising down the Nile, Malaka imagines a transnational future; as Gharib writes,

Tomorrow, I knew we’d be back here with our children. I probably won’t be able to translate Arabic for them . . . or understand the local customs. . . . But they’ll be able to feel the sun on their face, and the wind in their hair . . . and they’ll know, someday, somehow, that all this is a part of them, too. (American Dream, 154–56)

Gharib’s narrative thus ultimately refuses a singular identification or hegemonic understanding of US national belonging in these lines, as Malaka, now visually framed within an Egyptian landscape, realizes that whatever “all this” is, it is a part of her and her family, in all their multiplicities and complexities. The American Dream, for Malaka and other children of immigrants in the US, is found in these multiplicities, which are critical, interrogative, and transnational in outlook. Gharib’s text, like Abdelrazaq’s, thus resists the notion that living in the national sphere of the US is contingent on erasing forms of belonging to other national spaces and contexts, as both writers collapse over “here” and over “there” by embodying and bearing witness to “all this” in their differing but interconnected ways.

Unlike Abdelrazaq’s black and white storytelling, on top of black, the only colors Gharib uses as a visual hakawati are shades of red, white, and blue. Whereas Abdelrazaq’s text ends with Ahmad’s leaving the Middle East in pursuit of the American Dream, Gharib’s text, through its colors in particular, works more explicitly to bear witness to and affirm the author’s lived experience in America, restructuring and problematizing notions of national belonging for those “Othered” and rendered invisible, including children of immigrants born in the US. The predominant use of red, white, and blue throughout I Was Their American Dream engenders feelings of patriotism and American national belonging, but one that is critical rather than assimilative in nature. The use of these colors asserts and ascribes American national belonging for Gharib and her family members, despite and, subversively, because of their racial and ethnic multiplicities and differences (Image 5). In this visual subversion, the colors of America are used to redefine and bear witness to a multiplicity in understanding what it is to be American. As Malaka asks in her blog,

The process of telling my story made me finally understand something. I spent so much of my life trying to be an American. But all I had to do was look in the mirror. I was the daughter of immigrants, I was born in this country, and grew up in a town of immigrants—wasn’t that part of the American experience too? 38

Gharib’s methods of resistance as a visual hakawati are particularly interesting in terms of the participation she encourages from the reader, who is repeatedly asked to actively and visually engage in these explorations of multiplicities in identities, and, in turn, resist and refuse the homogeneity of US national discourses centered around “us” versus “them.” One page of the graphic novel, for example, is composed of boxed excerpts from Gharib’s real-life childhood journal with instructions on how to tear and fold the page so that, once completed, the reader will have their own minizine of Malaka’s journal (77–78). Now that readers are aware of how to make a minizine, Malaka also encourages them to “make your own!” This project is pertinent in two ways. First, as a miniature archive of Malaka’s life, this page is significantly different from the rest of the text. The page is colored in black and white, giving the feel of a nonfiction published work such as a newspaper. It has a real photograph of Malaka, the only one present in the narrative, as well as excerpts from her diary. As opposed to the font used in the rest of the text, which appears handwritten but is still computer-generated, this section’s excerpts are all composed of Malaka’s own handwriting. As a whole, the section is a unique new way for Malaka to visually and verbally bear witness to her own real-life identity as contemporary mixed-race Arab American, particularly at a time when Arab Americans are individually and collectively struggling over these racial and ethnic labels. Secondly, in asking readers to actively engage with Malaka’s differences and multiplicities, readers are also being asked to rethink racial “Others,” especially multiracial Arab Americans, in terms of their humanity, identities, and national belonging. Moreover, in declaring that readers should make their own minizines, readers are also encouraged to bear witness to their own identities in similar written and visual ways. Archive-making in this section is thus individualistic but speaks to and calls for a collective action in a transnational world abundant with differences that should be explored and made verbally and visually visible.

In another section that uses visuality and reader participation to critique homogeneity in American national discourses of belonging, Malaka reconstructs the struggles she faced in her attempts to fit in with the “white people” she went to college with at Syracuse University. Part of this performance of assimilation into Syracuse’s predominately white culture involves the inherently visual: how Malaka dresses. Gharib illustrates three different looks: the Game Day Look, the Frat Party Outfit, and the Business School Outfit. To dress Malaka in one of these looks, Gharib instructs: “Cut out this paper doll of Malaka. Then cut out the clothes and accessories. Dress her up to dramatically transform and alter her personality!” (96–97). Indeed, Malaka’s “personality” in terms of her identity is always changing, often depending on where she is and with whom. As readers are encouraged to dress up and transform Malaka in this section, these visual transformations are used to underscore how hegemonic notions of US belonging influence the identities and performances of those around us. Literally and symbolically dressing up Malaka brings to light the assimilative pressures and demands of US notions of belonging that readers are not exempt from and are ironically here asked not only to bear witness to but to partake in. This section thus interrogates the layers of performativity racial “others” have in terms of their identities, which are never static. It also makes evident constructions of whiteness and the “white-washing” that children of immigrants, particularly multiracial Arab Americans like Malaka, are subject to and partake in, critically engaging with these homogenizations (Image 6).

Another interactive section of the graphic novel that underscores visuality to critique and resist homogeneity in US national discourses and notions of national belonging includes flashcards Malaka has made for her future husband, Darren, which readers are encouraged to cut out for themselves. Each card has an illustration of one item, with the English word for that item written below and the Tagalog word for that item written above. By including this activity for readers, Gharib is encouraging readers to actively participate in verbally and visually learning about marginalized cultures, and bring different languages into an American national discourse that has often excluded them. Some of these flashcards depict traditional signifiers of Filipino culture, whereas other terms such as “eye booger” or “saliva,” help us recognize that all cultures have things in common, even the gross and mundane aspects of being human. Malaka then describes learning from Darren about white people, particularly American Southerners, which, in turn, makes evident the multiplicities and differences between American-born “white” citizens themselves. These cultural exchanges between Darren and Malaka bear witness to the types of cultural dynamism and hybridity being contended with in contemporary America. They underscore an inability to pinpoint a fixed identity, even for “white people,” making evident the abundant multiplicity that should be made visible in all American identities, regardless of race or ethnicity, but particularly for those “Othered” within US national discourses of belonging.

CONCLUSION

In 2020, I Was Their American Dream became the first graphic memoir to win an Arab American Book Award. Of this honor, Gharib notes “One of my deepest insecurities in life has been whether I was Arab enough [. . .] winning this honor from the Arab American Book Awards validates for me my experience as an Arab American—that whatever I knew about being Arab, whatever fears and worries I had about this side of me—that was enough.”41 Arab Americans today hold complex and multiple positionalities (as opposed to what is often simplistically and monolithically presented as their “Otherness”), and they hold complex connections to both the Arab homeland and the US. In this age of globalization, migration, and transnationalism, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to construct an “authentic” Arab or American identity, a contention both Gharib’s and Abdelrazaq’s texts reassert. As Abdelrazaq’s reconstruction of her ancestral past is foundational to her present as an Arab American child of immigrants, Gharib’s text serves as a primary example of how notions of identity, particularly for children of immigrants in America, are complex, dynamic, and difficult to label. Ultimately, both texts refuse assimilation into a homogenous US national discourse or positionality by bearing witness to their lived and inherited experiences, working to destabilize an “us” versus “them” binary reinforced, for Arab Americans in particular, after 9/11. As we see in Gharib’s conclusion, Egypt, the Philippines, and the US are a part of Malaka’s identity, as they will be a part of her future family’s. As Abdelrazaq’s work stands dedicated to the “children of immigrants who have not forgotten their parent’s stories,” both texts, in different but interconnected ways, draw on their individual pasts to bear witness to shared conditions of struggle for children of immigrants in the increasingly political and militaristic post-9/11 American present and future.

In introducing the term “visual hakawati,” I hope to provide a way of considering how transnational Arab artists today are engaging and building from traditional forms of visual Arab storytelling, constructing forms of contemporary critical resistance to hegemonic (mis)understandings of their identities and histories. This is perhaps nowhere more evident than in the flourishing medium of the graphic novel, in which Arab American as well as Arab artists around the globe are increasingly employing visuality as a mode of storytelling, using illustration to express what words cannot. Looking beyond Leila Abdelrazaq’s Baddawi and Malaka Gharib’s I Was Their American Dream, in the twenty-first century, Arab American artists such as Toufic El Rassi (Arab in America), and international artists such as Lamia Zaidé (Bye Bye Babylon), Zeina Abirached (I Remember Beirut), and Riad Sattouf (The Arab of the Future), have all used the medium of the graphic novel to create nonfiction memoirs of their own life stories and histories. In these graphic works, constructed across and within differing national contexts and connections, genders, sexualities, religions, subject matters, and illustrative forms, Arab artists speak across national borders and ideologies that flatten their identities, drawing over these misrepresentations of Arab histories and identities with unique and evolving visual forms of resistance. These graphic novels, which stand at the intersection of nations and cultures, past and present, are thus an important example of where Arab storytelling is heading.

NOTES

See, for example, Toufic El Rassi, Arab in America (San Francisco: Last Gasp, 2008); Lamia Zaidé, Bye Bye Babylon (Northampton, MA: Interlink Books, 2012); Zeina Abirached, I Remember Beirut (Minneapolis: Graphic Universe, 2014); Riad Sattouf, The Arab of the Future, 4 vols. (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2015–19); Iasmin Ata, Mis(h)adra (New York: Gallery 13, 2017); Sherine Hamdy and Coleman Nye, Lissa: A Story about Friendship, Medical Promise, and Revolution (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017).↩︎

My use of the term “Arab” here and throughout this article is done with the recognition of the fraught nature and tensions behind any stable or authentic notions of “Arab” identity. In this paper, the term “Arab” is meant to signify cultural, linguistic, political, and social connections between artists with origins in the SWANA region, while recognizing that the differences and multiplicities between peoples of this region are vast. In the same vein, my use of “transnational” here follows scholars such as Carol Fadda-Conrey, whose work traces the increasingly complex, dynamic, and non-uniform physical or metaphorical connections contemporary Arabs have to dual or multiple locations across national boundaries. Carol Fadda-Conrey, Contemporary Arab-American Literature: Transnational Reconfigurations of Citizenship and Belonging (New York: New York University Press, 2014).↩︎

See Cathy Caruth, ed., Listening to Trauma: Conversations with Leaders in the Theory & Treatment of Catastrophic Experience (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014).↩︎

Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History (New York: Routledge, 1992), 105.↩︎

As Hilary Chute claims, “There are many examples of the visual-verbal form of comics, drawn by hand, operating as documentary and addressing history, witness, and testimony.” Chute, Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form (Cambridge: Belknap, 2016), 2. Prominent examples of such comics include Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Joseph Sacco’s Palestine, but Chute also notes a growing number of other comics all over the globe—including graphic novels about Bosnia, Palestine, Hiroshima, and Ground Zero.↩︎

Hilary Chute, Why Comics? (New York: HarperCollins, 2017), 314.↩︎

See Jacki Lyden, “The Pull of the ‘Hakawati,’” All Things Considered, NPR, 18 May 2008.↩︎

Barbara Romaine, “Evolution of a Storyteller: The ‘Hakawâtî’ against the Threat of Cultural Annihilation,” Al-‘Arabiyya 40/41 (2007–2008): 259.↩︎

See, for instance, Mejdulene B. Shomali, who notes that because “Arab Americans struggle to craft their image within the discursive frames of difference and assimilation, [the figure of] Scheherazade offers a connection to an Arab literary history while inviting new narratives.” Shomali, “Scheherazade and the Limits of Inclusive Politics in Arab American Literature,” MELUS 43, no. 1 (2018): 67.↩︎

For example, the hakawati figure is engaged in early Arab American literature, such as Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet (New York: Knopf, 1923); as well as in more contemporary work, such as Rabih Alameddine, The Hakawati (New York: Knopf, 2008).↩︎

See the work of Arab American scholars such as Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1979); Jack G. Shaheen, Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People (Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press, 2012); Amira Jarmakani, An Imperialist Love Story: Desert Romances and the War on Terror (New York: New York University Press, 2015); Waleed F. Mahdi, Arab Americans in Film: From Hollywood and Egyptian Stereotypes to Self-Representation (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2020); Evelyn Alsultany, Arabs and Muslims in the Media: Race and Representation After 9/11 (New York: New York University Press, 2012).↩︎

As argued by Evelyn Alsultany in Arabs and Muslims in the Media, the end of WWII correlated with a shift of Western media representations of Arabs, from erotic and exotic fantasy into more representations of violence and terrorism, in correlation with the US’s increased political and military involvement and interventions in the Arab world. Alsultany, Arabs and Muslims in the Media, 7–8. These involvements include but are not limited to: the creation of the state of Israel in 1948; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967; the 1980s Cold War; US funding of the Mujahideen, the First Gulf War, and US invasion of Kuwait in 1991; and the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993. Lindsey comment: the way “US funding of the Mujahideen, the First Gulf War, and US invasion of Kuwait in 1991” is phrased made it seem like those three are grouped together, hence the inclusion of the semicolons for listing. If they are not, we can just use commas.↩︎

See Amaney Jamal and Nadine Naber, eds., Race and Arab Americans Before and After 9/11: From Invisible Citizens to Visible Subjects (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2008).↩︎

Steven Salaita, “Ethnic Identity and Imperative Patriotism: Arab Americans Before and After 9/11,” in Anti-Arab Racism in the USA: Where It Comes from and What It Means for Politics Today (London: Pluto Press, 2006), 75.↩︎

Chute, Why Comics?, 35–37.↩︎

Leila Abdelrazaq, Baddawi (Charlottesville: Just World Books, 2015).↩︎

I use disaster here to signal both the phenomena of “disaster” that Chute theorizes in her book, Disaster Drawn, but, also, the specific historical “disaster” of Palestine, the Nakba, which Abdelrazaq reconstructs in her graphic novel and which I discuss later in this section. For more on the Nakba, see Ahmad H. Sa’di and Lila Abu-Lughod, Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007).↩︎

As Abdelrazaq notes on Palestinian history in an interview with Tasbeeh Herwees, while writing her graphic novel, “That’s something that I was thinking about a lot, how Palestinian history transcends borders in that way and transcends the construct of the state.” Tasbeeh Herwees, “The Graphic Novel ‘Baddawi’ Looks Back at Life in a Palestinian Refugee Camp,” VICE, 5 December 2015, www.vice.com/en/article/9bg8g3/the-graphic-novel-baddawi-is-like-a-palestinian-persepolis-111.↩︎

Herwees, “The Graphic Novel ‘Baddawi’ Looks Back at Life in a Palestinian Refugee Camp.”↩︎

Juliane Hammer, Palestinians Born in Exile: Diaspora and the Search for a Homeland (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005), 42.↩︎

Baddawi is the name of the Palestinian refugee camp in North Lebanon that Abdelrazaq’s family was dislocated to. The camp’s name is derived from the Arabic word for “bedouin,” or nomad.↩︎

This widespread violence committed by “Zionist gangs” (Abdelrazaq, Baddawi, 18) across Palestine forced not just this family, but thousands of Palestinians from their homes, leading to what would historically be deemed the “Nakba,” or catastrophe. The Nakba refers to the historical flight or expulsion of more than 700,00 Palestinians (approximately half of the Palestinian Arab population) from their homes in Palestine during the 1948 war. See Sa’di and Abu-Lughod, Nakba.↩︎

Safsaf translates to “weeping willow.”↩︎

Reprinted from Abdelrazaq, Baddawi, 16.↩︎

Tasbeeh Herwees, “The Graphic Novel “Baddawi” Looks Back at Life in a Palestinian Refugee Camp.”↩︎

Grandmother and grandfather, respectively.↩︎

Naji al-Ali (b. 1938–d. 1987) is widely recognized as both the greatest Palestinian cartoonist and the most renowned cartoonist from the Arab region to date.↩︎

A prominent symbol of Palestinian resistance, Handala is a cartoon child drawn in a state of neglect and disarray, with his back always facing his viewer. He is never to grow up, forever ten years old, the age in which he left Palestine.↩︎

Reprinted from Abdelrazaq, Baddawi, front cover.↩︎

Ali Abunimah, Dear NPR News . . . (1998). The Link 31 (5): 1–14, quoted in Juliane Hammer, Palestinians Born in Exile: Diaspora and the Search for a Homeland. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005), 40.↩︎

Authors of The Invention of Tradition, a text that argues many traditions that “appear or claim to be old are often quite recent in origin and sometimes invented.” Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, eds., The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 1.↩︎

Hammer, “Palestinian National Identity, Memory, and History,” 41.↩︎

Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), 192.↩︎

Reprinted from Abdelrazaq, Baddawi, 108.↩︎

Malaka Gharib, I Was Their American Dream: A Graphic Memoir (New York: Clarkson Potter, 2019).↩︎

Gharib, “Who Gets to be American?,” PowellsBooks.Blog, Powell’s, 1 May 2019, www.powells.com/post/original-essays/who-gets-to-be-american.↩︎

Reprinted from Gharib, I Was Their American Dream, 67.↩︎

Gharib, “Who Gets to be American?”↩︎

Reprinted from Gharib, I Was Their American Dream, 74–75.↩︎

Reprinted from Gharib, I Was Their American Dream, 90–91.↩︎

“2020 Arab American Book Awards Include Award’s First-Ever Prize for Graphic Memoir,” ArabLitQuarterly, 31 August 2020, https://wp.me/pHopc-9QP.↩︎