Mija Sanders

DEATH ON THE AEGEAN BORDERLAND1

Abstract

In this article, I seek to change our understanding of necropolitics with regard to how host states and refugees themselves deal with their dead. Through technocratic practices for the former, and biophysical violence for the latter, I provide a reading of existing practices of processing the dead in which state and national boundaries follow migrants into the ground. I explore the necropolitics of displacement in order to understand Syrian affective experiences of shock, or sadma, under borderland policies, Turkish governance, and practices of intimate sovereignty in refugee deaths. Death for Syrian refugees on Turkey’s borderlands is the culmination of a series of transnational and local governance practices. It is also part of the material landscape of refugee displacement and of the Turkish government’s care sector—the processing of bodies and the conducting of funerary services. These services are meant to respond respectfully to frequent migrant deaths, despite the Turkish government’s warnings about the dangers of crossing the Aegean through human smuggling and the enhanced policing of the Aegean borderland meant to deter irregular crossings. For Syrians, however, police conduct on the Aegean borderland and the government’s management of memorials are contentious issues that enhance their sense of the necropolitical practices of governance and experiences of them as sadma. This work seeks to change our understanding of necropolitics with regard to how host states and refugees themselves deal with their dead, through twelve months of ethnographic fieldwork with Syrian refugees in Izmir, Turkey in 2017–2018.

INTRODUCTION

In this article, I seek to change our understanding of necropolitics with regard to how host states and refugees themselves deal with their dead. Through technocratic practices for the former, and biophysical violence for the latter, I provide a reading of existing practices of processing the dead in which state and national boundaries follow migrants into the ground. These bodies carry political meanings through their afterlives.2 Death for Syrian refugees on Turkey’s borderlands is the culmination of a series of transnational and local governance practices. “Necro,” referring to death, and “politics,” referring to the politics surrounding death, commonly define Achille Mcbembe’s term as the politics of letting certain groups die under otherwise preventable conditions (including intentional deaths by the state which, I argue, are framed as “accidents” of borderland policies3). This form of governance over migrant movement, such that people are pushed into riskier routes where death is more likely,4 constitutes a form of biopolitics—the management of life5—and a form of necropolitics, a concept that refers to “contemporary forms of subjugation of life to the power of death”6 under sovereign power through political circumstances. I include this meaning and extend it to include the processing of the dead through otherwise preventable biophysical violence after death through autopsies, which represent the intimate sovereignty of the state. By intentional deaths, I refer to the border regime of the European Union and the EU-Turkey deal, which prevent safe travel to the EU. Most refugees do not qualify for visas or asylum in the EU, and many do not find means of survival in Turkey, choosing to either return to Syria or face risky travel over the Aegean. Allegations of intentional boat sinkings by the Turkish coast guard are referenced, although not discussed at length. The highly securitized border regime itself is widely documented to increase refugee deaths in order to secure the borders of the EU at the cost of Syrian and other refugee lives.

The segregation of migrant bodies at the Turkish borderland and within Turkey, even within cemeteries, has biopolitical connotations regarding the governance of refugees by state institutions in Turkey.7 My use of biopolitics and necropolitics here is in line with recent scholarship on migration and border politics and their relationship to the increasingly frequent phenomenon of biophysical violence, “Whereby people are abandoned to the physical forces of deserts and seas, which directly operate on bodily functions with often devastating consequences,”8—a phenomenon that is easily observed on Izmir’s shores.9 In this way, death—including the processing of bodies and the conducting of funerary services—has become part of the material landscape of refugee displacement and of the Turkish government’s care sector. Even as the Turkish government has sought to deter irregular crossings by issuing warnings about the dangers of crossing the Aegean through human smuggling and enhancing policing practices in the borderland, it has offered services meant to respond respectfully to frequent migrant deaths. For example, the local municipality has expanded its care sector to include refugee forensic processing, mortuary work, and funeral rites.

The affective turn10 presented in this article is defined as shock, or in Arabic as sadma. Sadma was a term that emerged through ethnographic fieldwork with Syrians in Izmir 2017–2018 to describe feelings of shock and trauma that reverberated through many experiences of displacement in Izmir, Turkey. Sadma is key to understanding the impact of necropolitics for displaced Syrians. By drawing on the work of Ann Cvetkovich, who has argued, “Trauma becomes the hinge between systemic structures of exploitation and oppression and felt experience of them,”11 I recognize Syrian narratives about the processing of the dead as a political force and as a sadma. In this sense, sadma is part of the “hinge” between the political and the feeling of something—for Syrians, that includes the current context of exploitative economic structures, refugee governance, and the sad and shocking feeling of living through them. The hinge between politics and emotion shows us how sadma is a particular form of affect that permeates life. Syrians’ feelings of trauma—encoded in narratives of displacement—were connected to the ways in which the government and international organizations sought to support their lives.12 In many examples, traumatic shocks have collective and sociocultural (and often material) impact on the ways in which Syrians give birth, bury a relative, earn income, transit between borders, move resources, and make life and death decisions. Over time, trauma became an important mode of analysis as well, which informed my study of biopolitics and necropolitics, and oriented these dynamics politically.

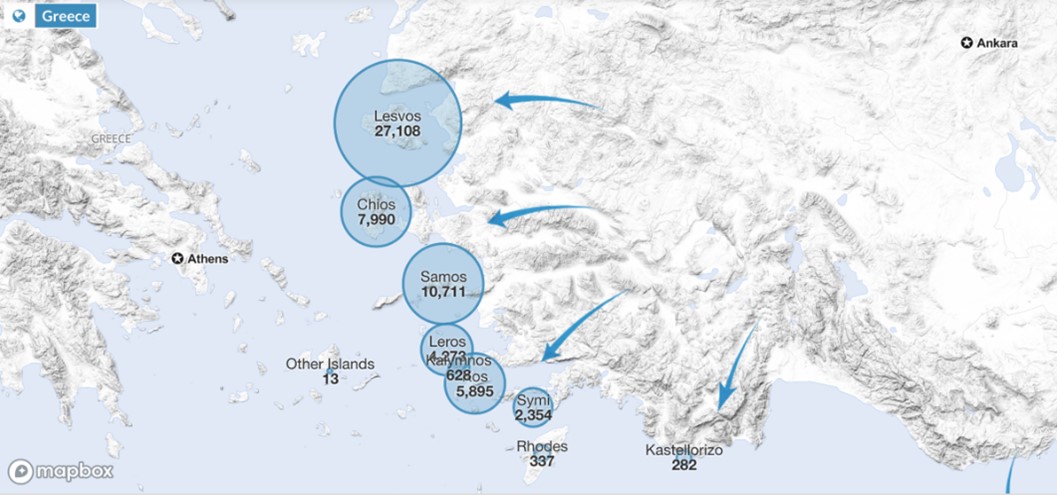

Located on Turkey’s Aegean coast, Izmir has been an ideal way station for Syrian refugees hoping to cross into Europe by sea, with the help of human smugglers. Indeed, it is estimated that in 2015 alone, 800,000 refugees and migrants made their way to Europe through the Izmir Aegean borderland.13 From Izmir, one could travel by inflatable boat to nearby Greek islands, a journey that—when it went well—would take anywhere from thirty minutes to a few hours.14 However, when the motor stalled or broke down, or when migrants lost their way in the dark, the tide could carry the boat astray or the boat could capsize. Such occurrences are unfortunately common; scholars have noted the frequent discovery of refugee bodies on beaches in Turkey and Greece since 2012,15 and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that 3,771 people drowned on the Aegean/Mediterranean coast in 2015.16 In 2016, travel slowed when the borders of Europe closed to refugees, halting the travel of thousands who had made it to Greece.

Nonetheless, travel across the Aegean has continued. I conducted fieldwork in Izmir for twelve months, from 2017 to 2018, and throughout that time, I noted the daily trips of rubber rafts across the Aegean. In 2019, the UNHCR counted 59,591 sea arrivals from Turkey to Greece. As already noted, however, many that make the attempt never arrive; in Greece alone, the UNHCR has reported the numbers of dead and missing between 2014 and 2018 to be 2,210 people.17 Yet that statistic does not include the number of dead and missing on Turkish shores. Those numbers are less often compiled by the Turkish government, though they are frequently reported in Turkish and international newspapers, and through more informal channels. On Facebook, for example, volunteers posted daily counts of arrivals and departures and updated numbers of drownings. In January 2019, one Iraqi volunteer for rescue missions on the Aegean Sea posted on the Facebook page that “2,262 souls” who had attempted to travel across the Aegean from Turkey to Greece in 2018 “were stolen at sea in order to search for peace.”18 In the first week of 2020, the BBC reported that a boat capsized off the shore of Çeşme, near Izmir, and eight children drowned. No one knows their origins.19

Because of its location, Izmir’s efforts in dealing with death, funerals, and refugee bodies are unique to the region. Given the danger of the crossing, Izmir is not only a key point on the transit route from the Middle East to Europe, but a cemetery for those fleeing conflicts and wars in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Its shores and resort beaches have become a discovery site for thousands of drowned bodies, of all ages. In turn, the phenomenon of refugee bodies washing up on Izmir’s shores have exacerbated an array of Syrian rumors and fears about their already precarious situation as refugees in Turkey.

For Syrians, then, police conduct on the Aegean borderland and the government’s management of memorials and other expansions in the care sector are contentious issues that enhance Syrians’ sense of the necropolitical practices of governance by the Turkish government.22 In this vein, this article focuses on the Aegean borderland, its sea and its beaches, its “nameless” migrant cemeteries, and the ritual processing of death. I explore the material contexts of refugee death through both bureaucratic and ad hoc memorials in order to make a connection between dignified and undignified deaths, refugee governance, and necropolitics in the context of Syrian Islamic norms of death, burial, and mourning. What effect does the way in which refugees are buried and remembered have, and on whom? How are these bodies political and politicized? What do state and solidarity rituals of belonging teach us about sovereignty over migrant corpses? And finally, what affective differences can be observed between these practices and the experiences and practices of Syrians who mourn the passing of their relatives?23 To address this last question, I offer the concept of sadma, the Arabic term for shock, as a lens not only for understanding the affective labor of sadma amongst refugees, but for understanding the segregative elements of borderland death and burial practices as political and othering.

Building on the work of existing studies on borderlands, death, and refugees in Turkey, and processing of the dead, I focus in this article on the effect on families of the dead and missing in states of migrant origin and on how bordering practices often have transnational and emotional impacts that transcend the EU boundaries,24 as well as Turkish state boundaries. This orientation serves to decenter EU- and US-based depictions of the “refugee crisis” that “focus exclusively on the EU (spatial) border and [are] shaped by security concerns.”25 Instead, I aim to offer a better understanding of how little information is available to those who seek to discover the fate of their loved ones.

To these ends, I begin with narratives of travel from two Syrian refugees, Shahira and Sorraya. Shahira’s story elucidates the context of survival in Turkey and risks of travel over the Aegean. In Sorraya’s story, we learn about the processing of the dead from her firsthand experience identifying her brother at the morgue after his death by drowning. Following Syrian experiences, I discuss the Turkish government’s indexing of a visual library of migrant corpses online, as well as Syrian narratives of moving through that deathly borderland and of receiving the bodies of relatives. Scholarship on the moral spectatorship and political responsibility of viewing migrant corpses has criticized the memefication and “living death.”26 At the risk of voyeurism and iterating a spectacle of suffering27 (a simple moral cause for the west), I connect the risks of travel over the Aegean to the Turkish government’s processing and display of dead in an online morgue. I share this archive not as a media representation of distant suffering, but with the intention of critiquing the practice by Turkish authorities, and aim of increasing awareness of its existence to further scholarly debate. Next, I interrogate the intimate sovereignty practices of the Turkish state through autopsy—a secular, technocratic practice—without consent from living family members. Finally, I situate meaning-making through the ritual processing of death in this dangerous zone, both through the state governance of Syrian bodies and through memorial rituals undertaken by Syrians and Turkish activists in solidarity with refugees. I also analyze the local government led by the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) practices of fictive kinship and segregative “intimate sovereignty”28 in cemetery grounds in Izmir. The local municipality governs the cemetery grounds, and the state-funded imam presides over Islamic funeral rites for unidentified migrant corpses. Thus, the study expands existing analyses of the Turkish government’s policies towards refugees into the graves of the Doğançay Cemetery in Izmir.

LITERATURES OF MIGRATION AND DEATH

Literature on Syrian refugees and on drownings in the Aegean has proliferated since the well-known death of Kurdish toddler Aylan Kurdi.29 In Izmir, the headline story of Aylan Kurdi, the Iraqi Kurdish toddler from Kobane who was found on the Izmir beach in 2015, became part of a larger geopolitical—and ultimately necropolitical—campaign to prevent migration to Europe. In contrast to the namelessness of many of the drowning victims in the Aegean, graphic depictions of the young infant Aylan Kurdi garnered focus in the international media and shocked the world.30 He became a “living ghost” online, the “tragic iconic” global figure circulating on social media and in newspapers.31 As Yasmin Ibrahim argues, “Dead ‘bare life’ gets a second screening online where it is abstracted into complex modes of production and consumption, which strip context and reposition, time and space, to release value and voyeurism.”32 Likewise, the stripping of context and time from images of the dead—whether through images in international media or in the Turkish government’s online morgue, is both a form of segregation from their normal lives in death and from the dignity required of Islamic burials. The impacts of this are political—specifically necropolitical—as a negative form of governance over refugees after death. In terms of consumption, the Turkish security industrial complex dehumanizes the dead through a lack of dignity and in its production of these images for consumption by the public. As much as the online morgue is a service, it is also a rendering of former life that is political in its stripping of dignity and lack of humanized burial in nameless cemeteries. Voyeurism on a grand scale produces another sadma, according to my interviews with Syrian refugees who have visited the morgue, and who have knowledge about the online morgue.

Existing literature on migrant deaths—and on deaths at political borders more broadly—is crucial for understanding the Turkey’s necropolitical governance practices and their relationship to EU policies. Studies of efforts to locate missing migrants and conduct rescue operations at sea have highlighted the inadequacy of such governance measures.33 This focus has drawn attention to migrant deaths on the Mediterranean as well.34 Some scholars have even analyzed death as the border of the EU, a border marked by inclusion and exclusion.35 The concept of the deathly border also expands the definition of the “war scene”—of an undignified and bad death through accident or violence beyond Syria to the shores of the Aegean—through the visual of bodies lying on the shore after refugees attempting to cross to the Greek islands have shipwrecked.36 Fleeing war and dying through boat accidents is as dangerous as the war itself. The online morgue itself represents another war scene. The findings of Kovras and Robins’ work on migrant deaths on the Greek island of Lesbos showed that there is a “‘grey zone’ around the management of migrant bodies, in which the obligations and responsibilities of a range of actors are ill-defined, enmeshed in legal and bureaucratic ambiguity.”37 Similar to Turkey, officials on the island of Lesbos place dead migrants in unnamed graves, marking the recycled stones used as tombstones with the migrants’ assumed nationalities and giving them each a number. For example, an Egyptian volunteer on Lesbos performed the Islamic washing ritual and buried the dead with their heads facing Mecca.38 Indeed, the identities of deceased migrants are often unknown. A similarly ad hoc process of visually identifying bodies in Turkey poses potential issues for grieving families, as I shall show.39

As noted in the preceding section, many migrant deaths are not recorded in official Turkish bureaucracy, a point that is important because the exclusion of migrant dead bodies signifies their place in the legal order.40 In turn, these legal and bureaucratic concerns inform the ways in which migrant bodies are presented and addressed as “grievable”—in Judith Butler’s terms—according to Izmir’s municipal practices for managing refugee bodies.41 Existing literature on burial, memorialization, and the value ascribed to human life informs the way I discuss migrant bodies in this paper. Although Agamben’s formulation of biopolitics did not see the corpse as inherently political, others have since argued that the very existence of a migrant corpse and “its presence at the border” is political.42 Indeed, the body itself can be read as a political subject.43 Squire, for example, has critiqued the framework of “dignity” as an intervention.44 In this vein, I use the term “undignified” to describe migrant bodies in an Islamic sense, in line with the norms of Islamic practices rather than with the norms associated with Western humanitarian intervention. Below, I elaborate on this point further through a discussion of norms of Islamic burial practices in order to make a connection between dignified/undignified in the context of necropolitics and governance, and the significance of sadma as an affective response to these politics.

Intimacy, in this paper, is forged through the gaze and through government handling of corpses and Islamic funerals. The public display of local and migrant corpses in undignified, unclean, and unclothed manners challenges the norms of public life in Turkey and the norms of death in Islam.45 In this way, Zengin’s theoretical path of “thinking sovereignty as intimacy and intimacy as sovereignty” guides my analysis of the segregation of “nameless” migrant bodies in an Izmir cemetery46 and the ways in which the Turkish government cares for the deceased through Islamic rituals, on the one hand, and the undignified display of unidentified corpses, on the other. The “unidentified” (belirsiz) and “nameless” (isimsiz) bodies of the deceased equate to homological structures of death for migrants. Unidentified bodies go into a nameless section of the Doğançay Cemetery.47 That is, there is a specific space for these bodies in Izmir. At the same time, the government recognizes these bodies as Muslim through rituals, which are conducted by a state-paid imam, Imam Kadir Çelenk. Yet the migrant bodies are buried separately from the country’s residents in a special segregated section, marking their difference from national inclusion.

TRAVEL OVER THE AEGEAN

The climax of liminality in many of the refugee narratives involves the fear and real threat of death. The families were stripped of cultural capital—from their knowledge of and habits of Syria down to linguistic capacity—and desperate to escape to asylum in Europe. The prospect of unending physical labor for paltry wages without recourse to rights challenged all who could to contemplate the illegal water-crossing to Greece. This involved the mobilization of significant amounts of money through working and saving, borrowing or liquidation of any remaining assets. . . not since leaving Syria had they faced such a risk of death.48

As Leila Hudson notes, travel over the Aegean is a desperate attempt to escape labor exploitation, language challenges, and an uncertain future in Turkey, as well as the shocks and reverberations of trauma accumulated in Turkey. The journey involves risking one’s life and often spending the remainder of one’s resources. Initially, the trips would cost an individual around $2,000, and half price for a child.49 In winter 2017, some smugglers were offering trips for $800.50 The costs of travel with smugglers changed according to the weather, the season, and were subject to demand. Summer was more expensive than winter, according to Syrians who quoted figures during our interviews.

Shahira, age 26 from Aleppo, tried to cross the Aegean Sea from Izmir to a Greek island on April 5, 2017.51 She was nine months pregnant. She alleged that while she was crossing the Aegean, the Turkish coast guard tried to sink their boat, which was overfull with other Syrians trying to enter Europe through a human smuggler.52 When their boat failed to sink, the Turkish police took them ashore. In the panic, Shahira went into labor on the beach and was taken to a Turkish hospital where she underwent a C-section. They left the placenta inside her uterus “to be taken out two months later,” she told me.53 On April 10, 2017, Shahira sat on a couch opposite me in a dimly lit apartment in the Basmane neighborhood in Izmir, holding her newborn baby. She had been taken in by another Syrian family that had a two-bedroom apartment and four children. Shahira was alone, as her husband had already traveled on to Europe. All the money she had was the money to leave Turkey. “I have nothing here and no one here,” she explained to me. She did not have the means to survive in Turkey and felt that her only option was risky travel over the Aegean through human smugglers. A Syrian friend of mine, Sorayya, had heard about her, and we had come to deliver some clothes for her baby. I had collected some old baby clothes and baby formula from an American friend in Izmir. Shahira was glad to have the items but informed me that she would be leaving again in ten days in an attempt to reach her husband in Europe. She was determined to get out of Turkey and make her way to Germany with her newborn baby. The police had told her that if they caught her again, they would deport her back to Syria. Despite the risks, and our pleading, she left. Ten days later, we got a text that she had reached Greece with her baby. She was one of the lucky ones.

My friend Sorayya, age 27,54 had lost her brother Mohammad in the spring of 2016, when he traveled across the Aegean in a rubber boat full of people. In her apartment in Izmir, she showed me several home videos of her brother swimming in their family pool at their summer villa outside Aleppo. At their villa, he grew up swimming often; “He was a good swimmer,” she told me repeatedly. Everyone in the family swam in the summers. Sorayya reflected that when his boat sank in a shipwreck in the Aegean, his swimming did not save him. The police found his twenty-seven-year-old body on the shore in Izmir. Up to that point, Sorayya had been living in an apartment in Izmir with Mohammad and without the rest of their family. She was alone when she was called to identify her older brother’s body at the Turkish morgue.55 Soon after, he was buried in the Doğançay Cemetery at the edge of the city in a special section dedicated to the “nameless” corpses of refugees and migrants. Sorayya asked to have his name marked on the grave, but he had already been allocated a number. That is an issue I will return to below.

AN ONLINE CATALOGUE OF REFUGEE BODIES IN THE MORGUE

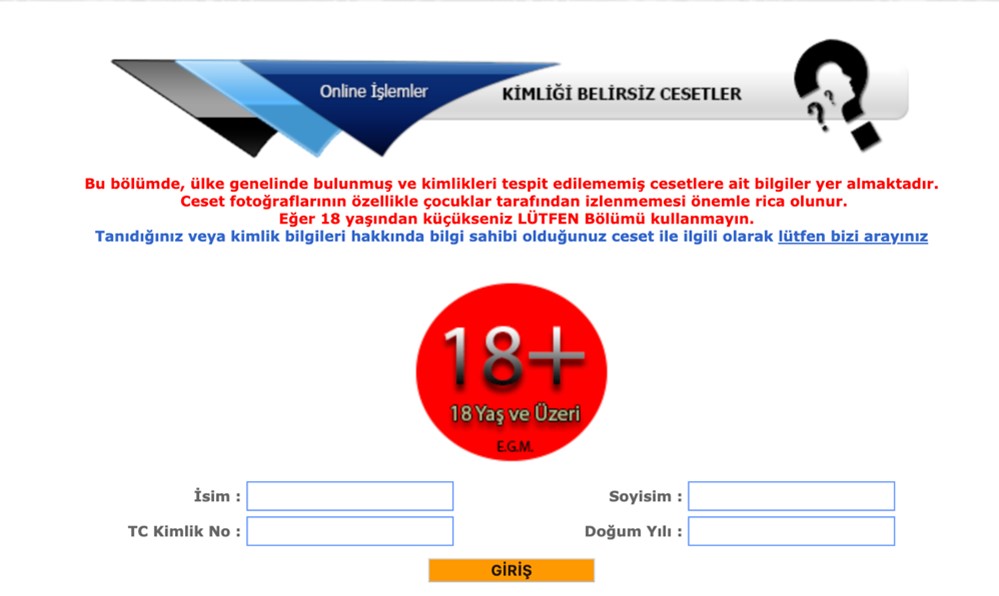

In 2017, in a Facebook group56 for humanitarian volunteers in Greece and non-governmental agencies, I discovered a link to a Turkish government website. As part of the search and rescue operations of nongovernmental organizations, efforts have been made to connect migrant families with the bodies of their loved ones.57 This website was meant to be a resource for family members to identify their deceased loved ones who had been catalogued in the police system as unidentified bodies. The Department of Public Security, under the Ministry of the Interior, created an online database to reflect the existing data on the bodies collected from Izmir shores.58 Families could give a DNA sample and have it matched with the DNA of an unidentified corpse. In theory, the Turkish bureaucratic system of identifying bodies was an effective and responsible response to the migration crisis. In practice, there were challenges to providing a DNA sample if family members were not in Turkey. In terms of visual identification, those seeking to find their loved ones would have to visit the entire Turkish morgue; survey a visual library of corpses, indexed by gender and the year they were found; and identify their loved ones based on rather shocking photographs.59 This was the only means of seeking information about one’s lost relatives.

I included the online morgue in my analysis as a key source of information for refugee families, NGO professionals, and volunteers. I juxtaposed the archive with ethnographic findings in order to emphasize the lack of other available information for NGO professionals and refugees, and in order to elucidate the problematic systems in place to track and process the dead, both online and for refugee’s family members. Without discussing the online morgue, a key piece of the Turkish state’s processing of the dead would be neglected. Further, it was through discussing the online morgue that discussions amongst Syrian interviewees about their own experiences of the morgue came forth. Little is known about how Turkish officials use this archive apart from their efforts to locate the living families of the dead. Amongst Syrians, my interviews on the topic were limited due to sensitivity60 and the fact that most families who had traveled over the Aegean were already located in Greece or in the EU, and were not included in this study.

The bodies were held in state morgues where relatives could visit and identify the bodies of loved ones within a two-week period. Members of the public could search through the database of images of the deceased bodies.61 The website is not for the faint of heart. When I visited the website in June 2017, I saw the bodies of Syrian individuals, including women fitted with hijabs and with their eyes held open, staring up into the camera from beds in the morgue. In Turkey, the website can be seen as a deterrent to illegal sea travel. It is a gruesome public archive of the dead, only available in Turkish. The images communicate through the use of deceased bodies, which serve as objects of warning for those who might risk traveling over the Aegean illegally.

In surveying the images, however, I noted highly problematic presentations of the unidentified bodies. Images of drowning victims—ostensibly discovered on Aegean beaches—were shown next to bloodied bodies presumed to be murder victims. Bodies were unclothed, with breasts exposed, and they were sometimes covered in the blood and dirt of the crime scene. I employed the assistance of a medical professional and former embalmer to analyze the images and provide insights into their status. The images were so traumatic that my research aide, a former embalmer working locally to my university in Tucson, Arizona, broke down upon seeing the images of brutally murdered children contained within the visual archive. Her assistance, however, was invaluable for gaining a better understanding of the police and municipality practices of managing refugee deaths. Sadma, or shock, was for us, and for any casual visitor to the site, a visceral experience.

As a researcher, I could not bear to revisit the images on the website after seeing them on my initial visit to the website in 2017. The impact of seeing the corpses affected me for several days. For the purposes of this article, I have relied on the descriptions of my research aide to document the presentation of local and migrant corpses within the Turkish police archive. I have focused on the bodies of women who were found between 2015 and 2018. I selected women because of the likelihood that their bodies would carry more readily identifiable symbols, such as headscarves. Specifically, I wanted to analyze the ways in which the government publicly displayed the bodies of Muslim women, with a headscarf or without, and whether modesty and dignity were part of the presentation.

Initially, when I first visited the website in 2017, I noted photos of women in headscarves and drowning victims. Eyes were wide open, sometimes held open by hands wearing latex gloves. The images included bodies found throughout the country. I visited a few pages of photos, with ten individuals depicted on each page. When I revisited the website with my research aide in 2019, she noted that murder victims dominated the site. There were fewer drowning victims and more victims of violence, as evidenced by the blood and dirt on the bodies. Various levels of decomposition could be observed, to the point that some bodies were so decayed that nothing but the pattern and color of the clothing could identify the individual. These were the website pages of photos that family members in Europe, or elsewhere, would presumably scroll through to see if their loved ones had drowned crossing the Aegean and had been found. Sadma was thus the visceral experience of anyone who visited the site and likely more so for family members of those whose photos might be discovered there. Despite the website being solely in Turkish, a few clicks brought one to the visual scenescape of murder victims, kidnap victims, and victims of drowning.

I use forensic evidence here as an object of ethnography for the purposes of understanding how the Turkish government processes the dead, how efforts are made to connect the dead with living family members, and to critique the practice. It is important to note that the pages of this index of bodies include all the dead and unidentified in Turkey. That means Syrians, Turkish citizens, and others who died anonymously within Turkish borders. Search criteria include gender and year the body was found. The following descriptions, rendered by my research aide, have been noted in order to emphasize the “tension” between “the bodies of migrants as evidence of a crime (the rhetoric of forensic truth) and a particular body as a reference point for mourning and the addressing of trauma (the rhetoric of memory).”62 In other words, the presentation of the bodies within crime scenes do not match the intentions of the family matching program. The police visual archives have been repurposed seemingly without any adjustment for public or family viewing. A warning button tells the view that they must be eighteen years or older to proceed through the site to view the images.

Upon mentioning this website to a humanitarian, the person responded, “The Turkish government is providing a service.”64 I evaluate this as part of a care sector of migrant services by centering Syrian refugee experiences, and the experiences of other refugees, as well as those of their allies. Although this service is better than nothing, it is traumatizing and causes more sadma. Using it involves contemplating the bodies of others and potentially amplifies one’s own personal loss. I describe these services and question their effectiveness within the framework of police objectives—to identify bodies through relatives and to provide information to the police to solve crimes—and of family objectives—to locate missing loved ones. On the bureaucratic and government level, objectives include caring for the bodies of the dead in cemeteries and governing the living through border policies intent on preventing more deaths. Turkish government medical interventions address the life cycle of refugees in the country. The final shock in this cycle is to see the body of a relative within the visual morgue of Turkey, in the midst of digging through image upon image of other bodies.

The bodies were presented in body bags or on tables. Their eyes were open. We began with photos from 2015. “The bodies are not clean,” my research aide Amanda commented. They were labeled with yellow markers positioned around their bodies. A yellow marker was placed by a woman’s foot at a crime scene. In another, yellow markers were placed around the socked foot of a girl child. She could be identified by her socks and the pattern of her clothes. Her face was not shown. What made the images so difficult to witness was the extent of violence, the fact that many children were included, and that many appeared to have been violently murdered or assaulted prior to death. Bloody bodies were indexed next to what appeared to be drowning victims, who may have been migrants.

Amanda narrated the photos to me so that I could gain a high-level sense of the process of visual identification and the management of migrant bodies by the government:

It is as if the bodies were photographed as is, just as they were found at the crime scene. It is very undignified. If they had taken any care it would have been much easier to see the bodies. If I was looking for a family member I’d be fucked up and traumatized if I saw this. As a former mortician and medical professional I wouldn’t have let anyone see bodies like this. In the funeral business we clean the bodies, close the eyes—we would never show a body like this to a family member. Even a sheet over their chests with a photo of the face would be better. It reminds me of a war scene, of bodies piled up. Similarly, they don’t lay them nicely.

She compared it to a holocaust scene. When bodies are damaged, piled, or placed precariously, they may lose their “individual integrity”65 and consequently become part of the material scene in which they were found. With this comparison, Amanda emphasized the difference in the presentation of bodies for the purpose of mourning by family members and their presentation for crime scene photography. That stark difference, and the conflation of the two for identification use, was highly problematic. The bodies were numbered 2,184 and the next 2,500, although by 2019, only twenty-four bodies from 2015 remained on the website. This raised the question of whether some bodies had been identified and removed from the site, leaving gaps in the numbers. It also raised questions about the total number of unidentified bodies for the year. Amanda continued to narrate her observations, much of which I tuned out: “Almost just a skeleton. . . . Unrecognizable . . . it has no clothes . . . just washed on shore. . . . The skin is waxy, like a drowning victim.”

The displaying of probable homicide victims from all over Turkey alongside the bodies of potentially drowned refugees—without demarcating bodies beyond the label of “unidentified”—resulted in a shocking visual archive; in essence, it required a visit to the entire morgue of unidentified bodies in Turkey. Bodies looked back at their viewers, from awkward positionings, in decay, and in blood and dirt. The final layer in a palimpsest of migration narratives—the unidentified dead as they lay in the moment of death. This is a visual archive upon which no one is prepared to gaze. The degradation of the human takes on Holocaust proportions as a war scene—not in numbers but in disfigurement. In terms of forensic evidence—and contrary to rites of burial for grieving families—the library of these human material records is ultimately a cemetery. From the Ahmet Piristina Archive in Konak to the cemetery hills of Bornova, I have traced migration records and materialities from the nineteenth century to the present, from the living to the dead, from the gaze to its reverberations, along with a spectrum of affects related to the politics of displacement. Bodies are also political, and they carry agency through their political impacts beyond the grave or the morgue. The intensity of watching Amanda gaze upon the dead was palpable. The shock of seeing children in such conditions was beyond words. Due to the low speed of the website, the webpages of the archive loaded so slowly that thirty minutes to an hour would pass between the loading of pages. That added to the difficulty of affectively processing and analyzing the images.

CEMETERY OF THE NAMELESS

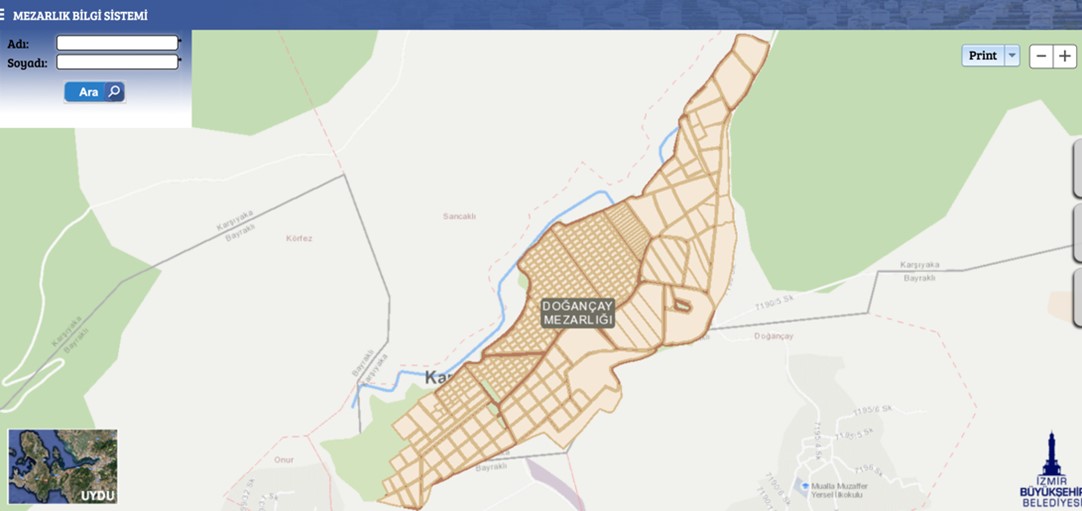

On the hills above the city rest the bodies of the “nameless” in graves marked with numbers in place of names.67 The cemetery pictured above is Doğançay Cemetery. State-run cemeteries hold the bodies of Syrians such as Sorraya’s brother Mohammad and thousands of others who died trying to cross the Aegean Sea. In 2016, Municipal imams reported conducting an average of five funerals a day.68 These graves form the nameless material space of the city’s taxonomy of bodies and the material remains of war, of migration gone wrong, and of those who died of health complications within the Izmir public health system. It is a site of visitation for organizations that mourn on behalf of distant families, for local Syrian families who have lost relatives, and for journalists. All of the deceased receive a Sunni Muslim funeral and are “mourned” vis-a-vis the Turkish government through the municipal imams.

Sometimes entire families drown when their boats capsize, and there is no one present to mourn them. In this case, what level of recognition of the anonymous deceased can be employed by the state? Are they recognized as migrants or as something else? Those who have no one present are mourned by the imam for the municipality. In terms of belonging in Balkan’s sense, the unmarked gravesites demonstrate the nonbelonging of deceased Syrians in Izmir. The mourning of these deceased people by the state, however, symbolically enfolds them through the Sunni Muslim ceremony, which recognizes them as subjects of state sovereignty. They are not mourned by the state as migrants, specifically, or as victims of human trafficking and geopolitical borderland policies. They are simply mourned as Muslims (whether or not they had been Muslim).69 The remains may be claimed for up to one hundred years. Among the relatives of the deceased, they are remembered through family photographs or sometimes identified visually or with a DNA sample.

When the Turkish authorities buried her brother, Sorayya performed the prayers alone.71 When her mother and younger brother joined her in Izmir from Aleppo shortly thereafter, their trip toward Europe ended. They decided to settle in Izmir so they could be near her brother’s gravesite and perform the annual rituals, thereby maintaining a sense of connection and Syrian belonging for the corpse. Her mother became depressed and did not leave their Izmir apartment for three years, waiting patiently for the younger son to arrive home each night from work. She held on to her remaining children emotionally, making sure nothing happened to them. In this way, Izmir marked a necropolitical part of their migrant experience through the body of her son.

The Izmir municipality maintains a separate cemetery information system through which visitors can look up the deceased through first and last name. The search box appears for the Doğançay Cemetery (mezarlık) appears below. Although the cemetery existed prior to the Syrian refugee crisis,72 it has been designated for the burial of migrants who cannot be relocated back to Syria and for the nameless bodies.73

POLITICS OF MIGRANT BODIES

Bodies become political objects with contested forms of sovereignty, both affective and familial, and in terms of government care and of bureaucratic organization. For unidentified corpses, the state ensures a good Islamic burial, but it also performs autopsies without consent. Recent work on bodies and burials in Turkey has addressed belonging and sovereignty as spheres of negotiation.75 Here, Zengin’s concept of “intimate sovereignty” is useful for analyzing the politics of migrant bodies, which are processed by the government. In her work on transgender bodies and their afterlives, Zengin argues that the deceased body “can open a social field for negotiation and contestation of sexual and gender difference among religious, medico-legal, familial, and LGBTQ actors.”76 For Zengin, death is a time when sovereignty and intimacy co-constitute through gendered registers of violence. There is a similar dynamic of sovereignty at work for Syrian bodies who have no one to claim them. Syrians also become objects of state power at the moment of death. What is unique for Syrians is that in cases of drownings in the Aegean, and their retrieval by the state into a taxonomy of nameless mortuary processing and burial, there is no one to speak on their behalf. In many cases, they were only traveling through, and no one was left in Turkey to claim them as family. Normally in Turkey, relatives of the deceased have sovereignty over decisions about death rights, such as burial practice, section of burial plot, and autopsy.77 Who has “intimate sovereignty” in these decisions can be contested among family members and spouses. In the case of unclaimed deceased Syrian individuals, however, Turkey’s hegemonic religious doctrine prevails over these decisions, including the dressing of bodies for the afterlife. In what would normally be the gendered performance of belonging in Turkish families, through funeral rites that include intimate practices of washing the body and preparing it for burial, these forms of intimate sovereignty are asserted by the state. Syrian travelers across the Aegean are all buried as Muslim (regardless of their religious identity—because it is unknown). In this way, all migrant bodies are interpolated as Muslim subjects of the state. Although refugees such as Syrians are considered Muslim-kin of the state, they lie in segregated cemeteries, maintaining a separation of nations even in the ground. The metaphor this brings to mind is the “safe zone” of northern Syria, governed by a Turkish occupation. The segregated cemetery in Izmir mimics this ethnic-national zone through difference in death. These are the politics of death rendered by the AK Party for Syrians. Migrant bodies are buried anonymously and processed as universal, reminding us of the mass graves symbolized through the tomb of the Unknown Soldier.78

Neglecting to pay attention to Islamic rituals for Syrian patients heightens Syrian perceptions of Turkey and Turkish governance as a necropolitical atmosphere where birth and death are dehumanized for Syrians living in Turkey. In the case of death and autopsy, the lack of consent and proper ritual burial (within twenty-four hours) was highly problematic for the families I interviewed.79 Further, they said that the cultural violation of disembodiment during an autopsy was a shocking medical intervention. The burials were too delayed for the individual to enter the next world in a good way, and the bodies were too disfigured.

FUNERALS OF BELONGING

Islamic funerals for deceased refugees have marked Muslim subjecthood for the Turkish state, but the government has not been the only actor performing burial rituals. Laura Wittman asks: “In contrast to ‘empty icons’ . . . what new symbolic forms, beholden neither to traditional religion nor to political ideologies, can we develop for mourning and healing?”80 Similarly, I wondered what other kinds of ritual belonging were being performed for migrants, known or unknown, in Izmir. I found one answer in the situation of a family from Kobane, in northern Syria. Having been barred from entry into Turkey, they sought the help of locals in Izmir in order to memorialize the death of their infant son, who was buried in Izmir. During the first two weeks of my fieldwork in Izmir, I visited a leftist pro-Kurdish NGO in Alsancak that was working to support refugees in Izmir. During an organizing meeting held in Turkish, doctors, nurses, lawyers, academics, activists, and other middle-class professionals sat around the conference table. A few European graduate students and I attended the NGO’s weekly meeting as guests and sat near the back so that I could translate for the non-Turkish speakers. Twenty to thirty people crowded into a small conference room and listened to the meeting agenda, which was announced by the group speakers. They discussed a few action items and their plan to distribute items to refugees in various informal camps on the periphery of the city. They planned a workshop about refugees with disabilities. Lastly, they had taken on the responsibility of holding an Islamic funeral for a Kurdish Kobane family, at the family’s request.81 Generally, they volunteered their services as nurses and doctors to treat refugees who had no identification or who could not access free medical services of the state because they lived in remote camps outside the city. Their work focused on the bodies of refugees in various ways. They were also tasked with taking care of the deceased, specifically with dealing with cultural and religious matters beyond the bounds of the body. They had been asked to take on the responsibility of performing an Islamic prayer and making a dessert for 300 people on behalf of the Kobane family who could not enter Turkey to perform the annual rituals on behalf of their deceased child. We had assembled to determine roles for the funeral ritual.

The group was volunteer based, Marxist oriented, and accepted no money. The surgeon who led the organization had promised a Kurdish family from Kobane, Syria, that he would perform an annual Islamic funeral ceremony for a Kurdish baby with a birth defect who died during a surgery he performed on the baby a year prior. The baby was born with his brain outside of his skull and had a low chance of survival. The family had been in Izmir and had returned to Kobane after the death of the infant. The family could not visit Izmir, and the state did not allow the group to send the body to Kobane. In the group meeting, the surgeon announced the event and asked if anyone in the room could recite the necessary prayers in Arabic. The room went quiet as they looked around. Someone said, “Despite being an atheist, I’m willing to do the prayer on behalf of the family, but I don’t know how to do it. Is there someone more qualified who is familiar with reciting prayers in Arabic?” Perhaps unsurprisingly, no present group members, despite their eagerness to help the family, knew how to recite the Quran and thus perform the rites. Finally, one woman in the room, who was wearing a headscarf, was chosen to recite the prayer, although she admitted she was not very confident in her Arabic. This secular, leftist group’s second task in organizing the memorial for the Kobane child focused on preparing and distributing to 300 people ölü helvası (helva of the dead) a sweet dessert and regional funerary custom.82 Once more, they looked around the room and could not find a volunteer who knew how to make desserts in large quantities, so the group changed it to another Turkish dessert that they could purchase and decided it was good enough. Thus, their visit to the cemetery to perform the memorial on behalf of the infant refugee from Kobane was planned accordingly. In this unusual circumstance, the group of secular, leftist doctors, nurses, and surgeons had been asked to perform affective and Islamic religious labor on behalf of the Kurdish family whom it was their mission to serve. Sometimes an uncanny circumstance, such as this one, was an unanticipated result of the refugee crisis due to the cultural and political makeup of those willing to help Kurdish refugees, who were considered politically suspect by many other local groups in Turkey. By performing the annual ceremony, the NGO performed the politics of inclusion and belonging for the infant body.83

CONCLUSION

In this paper the politics of shock were explored through family narratives and practices of sovereignty over migrant bodies in displacement. The impacts of this array of practices and policies in Turkey has produced biophysical violence, the tensions inherent to processing bodies for both crime investigations and mourning family identification purposes, and segregated burial. State and national boundaries have therefore followed migrant bodies into the ground. Not even their deaths can displace the function of borders. As Squire notes, the blame of migrant deaths is shifted to “‘natural’ forces” and the people who have put themselves at risk by attempting to traverse the border.84 In this way, governments elide responsibility for contributing to the conditions of migrant deaths-by-drowning on the Aegean borderland.

Migrant bodies are political in their afterlives—managed through the intimate sovereignty of the government, its mortuary practices, and the rituals of its imam. In Sorayya’s case, her brother was autopsied and buried, and his gravestone prepared as a number—all without her consent. She felt his body was violated after death for no reason. Sorayya performed the Islamic ceremony without the imam in order to assert what intimate sovereignty she had over the remembrance of her brother. The affective difference for Sorayya was a ritual form of belonging, which anchored Sorayya and her family to Turkey through her brother’s body because he could not be repatriated to Syria.

When decisions about burials are not available to families of the deceased, alternative rituals may mark their deaths or their induction into the bureaucratic system. Affective labor regarding burials is performed by three parties: 1) The imams of the municipality perform the rituals of Islamic Sunni prayer to interpolate Syrian refugees as Muslim siblings. 2) Members of a Marxist NGO that carried out the same ritual to perform belonging for a Kurdish infant, who would otherwise never be remembered as a Kurdish baby from Kobane—a site under Turkish military bombardment that is also politically suspect. 3) Family members like Sorayya who performed the same Islamic ritual for her brother, to remember him as a young Syrian man, in a nameless cemetery where he would otherwise be forgotten by the state after his initial rites were performed. The affective labor of mourning a horrific death was most profound for Syrians, who experienced compounded forms of sadma while living in displacement under Turkish state governance.

Forms of deterrence embedded within the bureaucratic practices of sovereignty over refugees, such as the public display of a visual archive of refugee death and the securitization of the borders through the policing of Aegean waters, demonstrate the state’s management of Syrian refugee bodies. Williams and Mountz offer empirical support to the idea that the increased enforcement of borders at sea does contribute to the loss of life as sea.85 As of 2019, the bare life conditions of the borderland continue to demarcate and construct the other, classifying and categorizing who can travel safely across the Aegean borderland, and who must travel at the risk of death. That occurs within the context of a political economy of life that exists for the maintenance of national boundaries, economies, and securities.86

One of the subtle arguments of this article is that biopolitical interventions are also a spiritual matter for many Syrians. In Islam, the way a deceased body is processed and regarded has implications for the next world.87 This particular form of Islam has to do with Syrian practices and beliefs grounded in Syrian Islamic traditions. In Turkey, these practices are markedly different from modern bureaucratic practices, which process the body through secular, technocratic interventions. Turkish biopolitics does not consider Syrian traditions of births, death, and blessings in the midst of its technocratic practices. For many Syrians, that failure is interpreted as necropolitical. Syrian Islamic tradition and Turkish technical modernity are thus disjointed in the domains of birth and death. The two co-constitute the other—secular modern practices and traditional Islamic practices—and make their differences clear. I argue, then, that the modern Turkish medical and mortuary procedures that render sovereign domain and its practices intimate—by technocratic means—amount to a spiritual crisis of a good Islamic death for Syrians. The necropolitics of displacement explored in this article helps to explain Syrian affective experiences of sadma under borderland policies, Turkish governance, and practices of intimate sovereignty in refugee deaths.

NOTES

Trigger warning: This article includes mention of potentially disturbing topics including death, explicit descriptions of images of corpses, and assault.↩︎

Iosif Kovras and Simon Robins, “Death as the Border: Managing Missing Migrants and Unidentified Bodies at the EU's Mediterranean Frontier,” Political Geography 55 (2016): 40–49.↩︎

Jasbir Puar, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 62.↩︎

See Kira Williams and Alison Mountz, “Between Enforcement and Precarity: Externalization and Migrant Deaths at Sea,” International Migration 56, no. 5 (2018): 74–89; also Marisela Montenegro, Joan Pujol, and Silvia Posocco, “Bordering, Exclusions and Necropolitics,” Qualitative Research Journal 17, no. 3 (2017): 142–54.↩︎

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books, 1977); The History of Sexuality (New York: Vintage Books, 1990); Society Must be Defended: Lectures at the College de France, 1975–76, ed. Mauro Vertani, Alessandro Fontana and François Ewald (New York: Picador, 2003); Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth (Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984, Vol. 1) (New York: New Press, 1997).↩︎

Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” Public Culture 15, no. 1 (2003): 39; see also Silvia Posocco, “Life, Death and Ethnography,” Qualitative Research Journal 3 (August 2017): 177–187.↩︎

See Aslı Iğsız, Humanism in Ruins: Entangled Legacies of the Greek-Turkish Population Exchange (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018). Iğsız’s research shows important connections between historical scientific eugenic racialism to the 1923 population exchange as “a legal reference point of segregative biopolitics in the international arena, or it can be more implicit, as examined in terms of logics of racialized thinking and biopolitics that have informed different practices of segregation” (21). Based on Iğsız’s study, it would be possible to do historical research to draw broader connections between scientific eugenic racialism and other forms of population management in Turkey, but that is beyond the scope of this paper. My work is informed, however, by thinking through relationalities between historical institutions on refugees and eugenics in Turkey, which emerged through Iğsız’s work. In this sense, a legacy of the governance of refugees in Turkey is certainly entangled with the legacies of scholars and their institutions which governed refugees historically in Turkey, producing discourses of difference and segregative biopolitics.↩︎

Vicki Squire, Post/Humanitarian Border Politics between Mexico and the U.S.: People, Places, Things (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2015), 514.↩︎

Biophysical violence has become “an established feature of contemporary border politics,” as can be observed on Izmir’s shores (Vicki Squire, “Governing Migration through Death in Europe and the US: Identification, Burial and the Crisis of Modern Humanism,” European Journal of International Relations 23, no. 3 (2016): 513). Recent studies of violence and migrant deaths have drawn on the concept of biopolitics, as well as on Agamben’s concept of bare life and Mbembe’s work on necropolitics. See Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998); Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019); Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” Public Culture 15, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 11–40.↩︎

The “affective turn” is an alternative to a psychoanalytical approach. It is for this reason that I have not chosen to translate sadma primarily as trauma, but as shock. I use affect, feeling, and emotion interchangeably as objects of cultural analysis and critical scholarly inquiry. The work of Cifor and Gillian inform my approach to the affective turn as well as my approach to the archive. See Marika Cifor and Anne J. Gillian, “Affect and the Archive, Archives and Their Affects: An Introduction to the Special Issue,” Arch Sci 16 (2016): 1–6.↩︎

Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 12.↩︎

See Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” 39; see also Posocco, “Life, Death and Ethnography.”↩︎

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Operational Data Portal: Refugee Situations,” accessed 15 July 2021, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean#_ga=2.163887679.1052613094.1579122390-936987826.1576252952.↩︎

“The trip between the Turkish coast and the easternmost Greek Island of Lesbos was short—in the best conditions, the voyage between Dikili in Izmir Province and the Lesbian capital of Mytilini could take as little as half an hour. The craft of choice became the small inflatable pontoon boat, and usually for much of the journey migrants were able to maintain contact with the outside world by cell phone rather than being independent on their smugglers. On most trips, the migrants were not piloted or guided but left to their own fate on badly overcrowded and under fueled rafts with no crew. The short crossing could last for hours.” Leila Hudson, “Syrian Refugees in Europe: Migration Dynamics and Political Challenges,” New England Journal of Public Policy 30, no. 2 (2018): 6.↩︎

Sarah Green, “Absent Details: the transnational lives of undocumented dead bodies in the Aegean,” in The Refugee and Migrant Issue: Readings and Studies of Borders Athens: Papazisi, ed. Sevasti Trubeta. For scholarship on numbers of Mediterranean migrant deaths, see Squire, “Governing Migration through Death in Europe and the US.”↩︎

These numbers include Syrian, Iraqi and Afghan nationals, and reporting from various authorities, presumably on both Greek and Turkish shores. “Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan for Europe-2016,” UNHCR Global Focus, accessed 23 July 2021, https://reporting.unhcr.org/node/13626.↩︎

“Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan for Europe-2016.”↩︎

The figure “2,262” is cited in an article by The Libya Observer, crediting UNHCR. See “UNHCR: 2262 Migrants Drowned or Missing in Mediterranean in 2018,”The Libya Observer, 5 January 2019, https://www.libyaobserver.ly/inbrief/unhcr-2262-migrants-drowned-or-missing-mediterranean-2018?fbclid=IwAR3VicAy6jP54rC-qvzoZaF-WVXrGEkgwUoWUCgXBEoAzCchosSaQBWlnJg.↩︎

“Migrant Crisis: Eight Children Die as Boat Sinks off Turkey,” BBC, 12 January 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-51081865.↩︎

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Operational Data Portal: Refugee Situations.”↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Posocco, “Life, Death and Ethnography.”↩︎

As a state performance of symbolic mourning, the imam maintains the cemetery and performs the necessary rituals. Personally, however, Imam Kadir Çelenk reflected xenophobic discourses about the Syrians for whom he mourned. “He was sympathetic to their plight, but as we spoke I realized that he believed several false stereotypes about Syrians, including that the Turkish government gives them preferential treatment. In an offhand comment he referred to Syrians receiving better access to health care than most Turkish people, refuting a suggestion that some of the children buried in Island 412 may have died due to poor health care. The contradiction in his attitude marks an uneasy tension, common throughout the country, between humanitarian sympathy and pragmatic duty. Syrian refugees were first welcomed into the country in part along the lines of religious fraternity. But recently, as the refugee population has grown, anti-Syrian sentiment has proliferated, exacerbated in part by an economic downturn.” Helen Mackreath, “The Border We All Cross,” Harpers, 9 October 2019, https://harpers.org/blog/2019/10/the-border-we-all-cross-dogancay-cemetery-izmir/.↩︎

Mackreath, “The Border We All Cross,” 41.↩︎

Ibid., 41.↩︎

Informing my notion of moral spectatorship and the consumption of distant suffering are the works of Lilie Chouliaraki, The Spectatorship of Suffering (London: Sage Publications, 2006); and Luc Boltanski, Distant Suffering: Morality, Media and Politics, trans. Graham D. Burchell, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

I borrow the term from Aslı Zengin, “The Afterlife of Gender: Sovereignty, Intimacy, and Muslim Funerals of Transgender People in Turkey,” Cultural Anthropology 34, no. 1 (2019): 78–102.↩︎

Penelope Papailias, “(Un)seeing Dead Refugee Bodies: Mourning Memes, Spectropolitics, and the Haunting of Europe,” Media, Culture, and Society 41, no. 8 (2018): 1048–68.↩︎

See Patrick Kingsley, “The Death of Alan Kurdi: One Year on, Compassion Towards Refugees Fades,” The Guardian, 2 September 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/sep/01/alan-kurdi-death-one-year-on-compassion-towards-refugees-fades; see also Anne Barnard and Karam Shouma, “Image of Drowned Syrian, Aylan Kurdi, 3, Brings Migrant Crisis into Focus,” New York Times, 3 September 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/04/world/europe/syria-boy-drowning.html.↩︎

Yasmin Ibrahim, “The Unsacred and the Spectacularized: Alan Kurdi and the Migrant Body,” Social Media + Society (October 2018): 7.↩︎

Ibrahim, “The Unsacred and the Spectacularized.”↩︎

Eugenio Cusumano, “Emptying the Sea with a Spoon? Non-Governmental Providers of Migrants Search and Rescue in the Mediterranean,” Marine Policy 75 (2017): 91–98.↩︎

Cusumano, “Emptying the Sea with a Spoon?”↩︎

Kovras and Robins, “Death as the Border,” 41.↩︎

Ibid., 41.↩︎

Ibid., 42.↩︎

Karolina Tagaris, “Unknown Dead Fill Lesbos Cemetery for Refugees Drowned at Sea,” Reuters, 14 February 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-greece-theunknown/unknown-dead-fill-lesbos-cemetery-for-refugees-drowned-at-sea-idUSKCN0VN0IV.↩︎

“Human rights organizations and international relief agencies have failed to provide a comprehensive account of the needs of families, who beyond the dead themselves are the primary victims of the neglect of migrant bodies. Indeed, the families of those dead and missing—with the exception of a few high profile cases—are entirely invisible in approaches to the phenomenon.” Kovras and Robins, “Death as the Border,” 43.↩︎

Agamben, Homo Sacer; Kovras and Robbins, “Death as the Border.”↩︎

Judith Butler, “Precarious Life, Vulnerability, and the Ethics of Cohabitation,” The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 26, no. 2 (2012): 134–51.↩︎

Kovras and Robbins, “Death as the Border,” 43.↩︎

Katherine Verdery, The Political Lives of Dead Bodies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000); Kovras and Robbins, “Death as the Border.”↩︎

Squire, “Governing Migration through Death in Europe and the US.”↩︎

In conversations with Anne Betteridge and Leila Hudson in December 2019, it became clear that it is important to note that visual access to bodies in Islam is something private to certain family members, in certain cultural contexts. For example, a sister may have access to seeing a body while a husband is prevented access. This has large implications for the visual display of bodies online.↩︎

“Some 15 refugees were buried in the cemetery in 2014, rising to 62 in 2015. A drastic increase was then seen in the first two months of 2016, when 59 refugees were buried in the cemetery. The dead bodies of the refugees are kept in a morgue for 15 days after the autopsy. If no one claims the dead body, then it is sent to the Doğançay Cemetery after the DNA sample and a photograph is taken.” See Banu Şen, “Cemetery of the Nameless Established in Turkey’s West for Syrians who Died En Route to Greece,” Hurriyet Daily News, 27 April 2017, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/cemetery-of-the-nameless-established-in-turkeys-west-for-syrians-who-died-en-route-to-greece--112477.↩︎

Mackreath, “The Border We All Cross.”↩︎

Leila Hudson, “The Refugee’s Passage: Liminality, Gendered Habits, the Emergence of Difference in Flight,” in Women and Borders: Refugees, Migrants and Communities, ed. Seema Shekhawat and Emmanuela C. Del Re (London: I.B. Tauris, 2018), 49–50.↩︎

Hudson, “Syrian Refugees in Europe,” 6.↩︎

Interviews with Syrian refugees by author, Izmir, Turkey, 2017–2018.↩︎

All persons referenced from interviews are protected by pseudonyms. As such, the name Shahira is a pseudonym. Interview by author, Izmir, Turkey 10 April 2017. Follow up was completed via text message.↩︎

Such scenes were common in 2015–2018. In 2015, I conducted numerous interviews with volunteers of the Yezidi Rescue Team (Yezidi and Christian Iraqi volunteers) who remained on mobile phone lines with refugees while they crossed the Aegean from Turkey to Greece in rubber boats. They witnessed numerous shipwrecks and identified the religious orientations of passengers when they witnessed the reciting of the shahada, the final prayer for Muslims before death. Such scenes were shocking to witness. Many informal groups and NGOs counted the bodies as they arrived on Greek shores after failed voyages. Groups like the Yezidi Rescue Team sought to connect irregular travelers with the Greek coast guard to ensure timely rescue.↩︎

Shahira, interview by author, Izmir, Turkey, 10 April 2017.↩︎

Author’s conversations with Sorraya began in early March 2017.↩︎

His body had been autopsied. This led Sorayya to question whether organ trafficking had occurred. She asked me why drowned bodies would need an autopsy if it is apparent that they drowned. Interview by author, Izmir, Turkey, September 2017.↩︎

Specific online groups to locate missing refugees include: https://www.facebook.com/unitedrescuesmissingpersons/; https://www.familylinks.icrc.org/en/Pages/HowWeWork/How-we-work.aspx?fbclid=IwAR2QdNtlkSW0LenzNHAECAVuYEdY1Xe4O_VoLgDTMFbq1Ja0Wru_qjbeEvQ. Users of the ICRC website are directed to contact the Turkish Red Crescent at tracing@kizilay.org.try. Accessed July 15 2021.↩︎

According to Sam Salih, a volunteer with refugee organizations in Greece and Germany, “the issue of tracking drownings and missing persons is a huge matter for refugees. Many are still seeking their loved ones after six years. I know a Syrian family in Hanover, Germany who are still looking for their children who crossed the Aegean to Greece six years ago. They were never found.” The interview with Sam Salih was conducted remotely on 15 July 2021. At time of publication it is not known what efforts the family has taken to locate their missing children.↩︎

Trigger warning: Sensitive material and graphic images are included in the following source. I am sharing the website here in case it is useful to others trying to identify relatives. Emniyet Genel Müdürlüğü (Turkish National Police), “Belirsiz Ceset (Unidentified Bodies),” accessed 16 December 2018, http://www.asayis.pol.tr/Sayfalar/KimligiBelirsizCeset.aspx. At time of publication, the website is no longer active. The Turkish military maintains a similar website, accessible via https://vatandas.jandarma.gov.tr/EDevlet/EDevlet. The website’s description states “In this section, there is information about the bodies found throughout the country and whose identities have not been identified.” It is possible that the website ownership has been transferred from the national police to the military.↩︎

On photos of the deceased, see the work of Laura Wittman. The first case of censorship came about in 1916 at the bodies of “dying sons” were displayed in documentary footage in Italy. Wittman reflects on the ways in which “real deaths on film are so disturbing” due to “aesthetics and their ethical and existential implications.” Laura Wittman, The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Modern Mourning, and the Reinvention of the Mystical Body (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 149, 140.↩︎

I did not conduct interviews with Syrians on the topic of death unless they introduced it in the course of conversation. My main interview question for Syrians was, “What are your problems?” Death was one of the issues which arose out of twelve months of weekly interviews with over 100 individuals.↩︎

The following source provides a news article about an Afghani refugee who searched for his family’s remains. It describes the Turkish system of dealing with migrant bodies and DNA identification. Fariba Nawa, “DNA Might Help Him Identify His Family but He Can’t Find a Way to Give a Sample,” PRI, 21 August 2017, https://www.pri.org/stories/2017-08-31/dna-might-help-him-identify-his-family-he-cant-find-way-give-sample#comments.↩︎

Kovras and Robbins, “Death as the Border,” 46.↩︎

Trigger warning: Sensitive material and graphic images are included in the following source. I am sharing the website here in case it is useful to others trying to identify relatives. Emniyet Genel Müdürlüğü (Turkish National Police), “Belirsiz Ceset (Unidentified Bodies),” accessed 16 December 2018, http://www.asayis.pol.tr/Sayfalar/KimligiBelirsizCeset.aspx. At time of publication, the website is no longer active. The Turkish military maintains a similar website, accessible via https://vatandas.jandarma.gov.tr/EDevlet/EDevlet. The website’s description states “In this section, there is information about the bodies found throughout the country and whose identities have not been identified.” It is possible that the website ownership has been transferred from the national police to the military.↩︎

This service, however utilitarian, was better to have than not to have.↩︎

Laura Wittman writes, “What was at stake . . . was that proper burial required identification and repatriation, that is, re-establishing the connection between a dead body (initially perceived by mourning as a frightening ‘thing’ which both is and is not ‘my loved one’) and some sort of enduring identity. . . . On the other hand . . . in many cases the bodies of the dead were so damaged and piled together that they post their individual integrity, and could not be separated from each other, or from the mud in the trenches.” Wittman, The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, 19.↩︎

Image from Ceylan Yeginsu, “Constant Tide of Migrants at Sea, and at Turkish Cemetery,” New York Times, 13 February 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/14/world/europe/constant-tide-of-migrants-at-sea-and-at-turkish-cemetery.html.↩︎

Şen, “Cemetery of the Nameless”; see also Sibel Hurtas, “Nameless Graves Leave Grim Reminders of Refugee Plight on Turkey’s Coasts,” Al-Monitor, 22 July 2016, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2016/07/turkey-syria-refugees-nameless-graves.html.↩︎

Ceylan Yeginsu, “Constant Tide of Migrants at Sea, and at Turkish Cemetery.”↩︎

In discussing this funeral practice with the Yezidi community in the US diaspora, one woman remarked, “My family would be horrified if our relative were buried as a Muslim after dying in the Aegean.” (Author interview with a Yezidi family who resided in a refugee camp in Turkey, Tucson, Arizona, September 2018). The politics of such burials could certainly be contested by some families of the identities of individuals were known.↩︎

Bryan Denton, “Constant Tide of Migrants at Sea and at Turkish Cemetery,” New York Times, 14 February 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/14/world/europe/constant-tide-of-migrant.↩︎

As a family member of the deceased man Mohammad, Sorayya had limited options in making decisions for her brother’s body. The situation in Syria makes it difficult to repatriate corpses. Questions of where to bury a body are rarely available to Syrians, if a choice exists at all. Osman Balkan writes that “corporal assertions of belonging deploy the body as an anchor” (Osman Balkan, “Burial and Belonging,” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 15, no. 1 (2016): 129). Due to the lack of alternative choices, Mohammad symbolically anchored her mother, herself, and her younger brother in Turkey. For Sorraya, it simply meant that they were not planning on going on to Europe anymore. Sorraya later married another refugee in Izmir, furthering her relationship to the city and to her future in Turkey. For her younger brother, however, the crisis of his brother’s death made it difficult for him to return to Syria to marry his fiancée once his mother and sister had settled in Izmir, and once he had secured a job in Izmir. The long-term citizenship implications for each of them were very much affected by their brother’s death.↩︎

See “Doğançay Cemetery is Growing,” Izmir Municipality website, 13 December 2012, https://www.izmir.bel.tr/tr/Haberler/buyuksehir-dogancay-mezarligini-buyutuyor/9021/156↩︎

It is unclear whether the cemetery only holds nameless migrants or whether it also holds local nameless murder, violence, and suicide victims as well.↩︎

“Cemetery Information System” (Mezarlik Bilgi Sistemi) of the Izmir, Turkey municipality, accessed 25 July 2021, https://cbs.izmir.bel.tr/CbsUygulamalar/MezarlikBilgiSistemi/mezarlikjs/?MezarlikID=4.↩︎

Zengin, “The Afterlife of Gender.”↩︎

Ibid., 98.↩︎

Ibid., 84.↩︎

Wittman, The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, 19.↩︎

The fusion of Syrian traditional world views—which include women, the elderly, and children being particularly vulnerable—provides a more intense version of necropolitics. Rhetorically, Syrians often remark that, “If I knew what it would be like, I would have stayed to die in Syria.” Turkish biopolitics does not consider Syrian traditions about births, death, blessings as instrumental to their world views and interpretations of experiences. In the technocratic coldness of secular-modern medical interventions in Izmir, biopolitical measures came across as necropolitical.↩︎

Wittman, The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, 19.↩︎

For further discussions on funerals, see Osman Balkan, “Between Civil Society and the State: Bureaucratic Competence and Cultural Mediation Among Muslim Undertakers in Berlin,” Journal of Intercultural Studies, 37, no. 2 (2015): 147–61; Balkan, “Burial and Belonging,” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 15, no. 1 (2016): 120–34; Balkan, “Until Death Do Us Depart: The Necropolitical Work of Turkish Funeral Funds in Germany,” in Muslims in the UK and Europe, ed. Yasir Suleiman (Cambridge: Center of Islamic Studies, 2015).↩︎

Zengin notes that “Helva is a dessert prepared with semolina or flour, sugar, and butter, and then cooked and served by the deceased person’s family for the participants of the funeral following the interment. As people eat helva, they also talk about the departed and remember them.” Zengin, “The Afterlife of Gender,” 91.↩︎

My thinking on belonging is informed by Osman Balkan, “Burial and Belonging.”↩︎

Squire, “Governing Migration through Death in Europe and the US,” 522.↩︎

Williams and Mountz, “Between Enforcement and Precarity.”↩︎

Green, “Absent Details,” 576; Montenegro, Pujol, and Posocco, “Bordering, Exclusions and Necropolitics,” 143–144.↩︎

“The radical idea that the Prophet Muḥammad taught and proclaimed through the early revelations of the Qurʾān was not that death was a certainty (which the pre-Islamic Arabs understood). Rather, he proclaimed that death was an opening to an afterlife and that the sudden shock of death associated in vivid imagery with both natural evils such as earthquakes and moral evils such as witchcraft required that humans understand the message from God to recognize him and to take on a moral obligation to live a good life culminating in a good death so that they may enjoy the fruits of that life and death in everlasting life hereafter.” Sajjad Rizbi, “A Muslim’s Perspective on the Good Death, Resurrection, and Human Destiny,” in Death, Resurrection, and Human Destiny: Christian and Muslim Perspectives, ed. David Marshall and Lucinda Mosher (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2014), 69.↩︎