Lea Müller-Funk

TRANSNATIONAL POLITICS, WOMEN & THE EGYPTIAN REVOLUTION: EXAMPLES FROM PARIS

Abstract

The revolutionary process in Egypt since 2011 has not only mobilized masses in Egypt, but has also led to a massive politicization and polarization of Egyptian communities abroad. Women from different generations became active in the protests claiming their agency to participate in changing their country. Cyberactivism became a particularly important vehicle for women to participate politically in the revolutionary process. This paper looks at transnational political networks in Paris working to influence politics in Egypt in the (post)-revolutionary phase between 2011 and 2013 with a special focus on women. An analysis of thirty informative-narrative interviews and several popular Facebook pages of diaspora networks reveals how women participated alongside men in transnational mobilizations in Paris, and how they experienced and lived these moments as they took part in their struggle. Several factors shape the political participation of women in this diasporic context, the gendered character of Egyptian migration to France itself, an inner fragmentation and politicization among women and finally, women’s broader understanding of politics blurring the traditional boundary of public and private. Contrary to assimilation theory, most participating women are not marginalized or poorly educated immigrants, but are on the contrary well educated and socially well connected.

INTRODUCTION

The revolutionary process in Egypt since 2011 has not only mobilized masses in Egypt, but has also led to a massive politicization and polarization of Egyptian communities abroad.

During the Arab Spring, the question on how Arab diasporas were involved in the uprisings was highly debated, especially in media, but little serious academic research exists so far, including the Egyptian diaspora.1 Even less is known on the extent to which Egyptian women in the diaspora participated politically in the (post)revolutionary process and, more specifically, how cyberspace was used to foster Arab women’s transnational activism. Thus, the purpose of this article is to analyze the role women played in Egyptian transnational political networks in Paris in the (post-)revolutionary process, how cyber activism was, and continues to be, used by them and what challenges female activists face.

The revolution in Egypt heavily affected the migratory outcomes within the region and internationally. Following the uprising in 2011 and Egypt’s unclear foreign policy, there has been a change in labor laws in some Arab countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, resulting in a slowdown of new contracts and work permits for potential migrants, opening up other migration options, such as—mostly irregular—migration to Europe. As a result of the crisis, many European countries reacted by either lowering the quota for migrants or making the procedures for legal migration more difficult.2 The impact of the revolutions in the Middle East on the volume of remittances to Egypt is still unknown. However, the suspicion is of a slight decline in remittances due to the repatriation of Egyptian migrants from areas of unrest, especially Libya.3 However, the uprisings did not only affect remittances and migration policies, but also lead to a more intense interest in Egypt and a renewed feeling of patriotism among Egyptians living abroad. Even if the revolution has to date achieved very few of its political aims, it has achieved one major aim in giving Egyptians back a sense of belonging and a will and ability of participating in affairs of public interest4 which was perpetuated also in its communities abroad. Several proposals were made by the Egyptian diaspora to support the Egyptian economy, such as the Tahrir Square Foundation seeking to use the resources of the overseas Egyptians to assist in problems at home.5 Other proposals included the idea to use the savings of individual Egyptians abroad to start projects in Egypt or even to return to Egypt in order to invest with knowledge, expertise and savings in the development of the country.6

During the upheaval of the immediate Arab Spring revolution in January and February 2011, women became very present as political activists in the public sphere and on graffiti – targeting sexual harassment of women, particularly during political protests – often in stark contrast to the persistent perception in the West of Muslim women as oppressed victims who have little agency. As protests grew, women from different generations and socio-economical background became highly active in the on-going anti-regime protests claiming their agency to participate in changing the country. 7 Accounts on how women and men mixed in public places seemed to temporarily have suspended traditional gender roles leading to expectations how women would continue to shape their country’s destiny after the upheavals. Especially cyber activism has been an important vehicle for women to participate politically in the revolutionary process in the Arab countries. Prominent examples were Lina Ben Mhenni, a Tunisian female blogger who tweeted and reported on Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation or Asmaa Mahfouz who called out to women and men in January 2011 to participate in the January 25 demonstrations by uploading videos on social networks. However, Arab women’s use of cyberspace and social media outlets as a means for activism far predates the Arab Spring, due to the fact that the internet can be safely and anonymously used from women’s homes. As Rita Stephan has shown, Arab women have been using the cyberspace to organize collectively since the 1990s. In fact, the internet is among the few spaces outside mainstream politics that are accessible to minorities and women’s activism.8 Stephan argues that the nature of cyberspace is particularly suitable and familiar to women’s activism, because “its lack of institutional and cultural norms is similar to the nontraditional spaces that the women’s movement has created since its beginning.”9 However, cyberspace is in itself a contested space for power struggles and has become a domain where gender relations take place.10

This article gives an insight into how women participated in the Arab Spring uprisings by analyzing transnational mobilizations in Paris. First, I discuss how the revolution in 2011 lead to an increased transnational political participation in Paris which included women. Second, I move to an analysis of cyber activism of transnational political networks in Paris. Finally, I analyze challenges for the political participation of women in a diasporic context.

METHODOLOGY

This paper is based on data I collected in Paris between September and December 2013. During this field research, I followed transnational political networks in Paris trying to influence politics in Egypt in the (post)-revolutionary phase between 2011 and 2013. Ostergaard-Nielsen defines transnational political networks as “transnational political practices, their links and organizations engaging in political processes in their country of origin.”11 The networks I studied varied in orientation, size and organization structure, some were openly political, such as the Association of Young Egyptians of the 25th of January Paris, the Association of Young Egyptians of the 25th of January France, Voices of Egypt, the 6th of April Movement France, the French Tamarrud Campaign, the Collective for the Defense of Democracy in Egypt, the Women Movement against the Coup d’Etat, and some had no open political agenda, but served as forums for political discussion on a second degree, such as the Coptic Solidarity, Blogcopte, France-Egypt Club and the Franco-Egyptian Organization for Human Rights.

Methodologically, I studied these networks on two different levels. On the one hand, I conducted around thirty informative-narrative interviews12 with people active in transnational political networks, so-called “transnational activists.” Sidney Tarrow has defined transnational activists as:

individuals and groups who mobilize domestic and international resources and opportunities to advance claims on behalf of external actors, against external opponents, or in favor of goals they hold in common with transnational allies.

I decided not to choose a specific age segment or limit the interviewees to the first, second or third generation, but tried to reach a maximal scope of age and generation to get a broad impression of participation. My aim was to interview the most active people in these transnational political networks. Thus, I did not aim to reach an equal gender balance, but interview the most active people in these networks. I used the snowball technique with different entry points to avoid getting a biased picture. In total, I conducted twenty-five interviews with men and six with women.

Secondly, I undertook an analysis of the cyber activism of these networks. In my case, research on networks on Facebook was particularly promising, as Facebook was the central tool for mobilization and organization of these networks. From a methodological perspective on social networks, the web is social and informational—it is about what holds the network together and what is discussed in it.13 I first conducted a content analysis of these networks on Facebook to study its content. I followed-up networks’ profiles on Facebook, translated their content and discussions and then analyzed them on the basis of the following questions:

How active, how popular is the page?

How are postings and comments written (German, Modern Standard Arabic, Egyptian dialect)?

Who writes? Who comments?

What kind of links is posted? How is the page connected to other websites and Facebook groups?

What subjects and themes are mainly written about?

To study the social character of these networks, I used a digital methods approach.14 Networks as such are hybrid objects formed by social actors and the links between them. Not new as such—applications exist since Jacob Moreno’s sociograms in 1934—this concept has known a revival in the last years, due to the development of a series of mathematic techniques making the analysis of complex digital networks possible, as well as the increasing availability of software to analyze and visualize graphs. Software programs such as Gephi can make these networks visible as graphs, emphasizing their primary elements. Actors are visualized as nodes, while links between actors are shown as edges, thus creating graphic maps. These visualizations make it possible to read networks like maps. The most connected actors can be seen with one click, their links, the numbers of actors in a network, as well as clusters of interconnected actors. I used the application Netvizz developed in 2009 by Bernhard Rieder from Amsterdam University to extract Facebook profiles and pages of political networks I studied. I then used the software program Gephi to visualize these networks. In my analysis, I hid users’ Facebook names in order to keep their anonymity in spite of the majority of users not trying to remain anonymous.

WOMEN ACTIVISTS IN TRANSNATIONAL POLITICAL NETWORKS IN PARIS

A new sense of collectivity including women

In Paris, the reconfigurations and political mobilizations that have taken place since January 2011 reflect the political events in Egypt. What can be observed are strong dynamics from Egypt influencing Egyptian social fields abroad, on a political, but also on a very personal level. Generally, the uprising in January 2011 served as a moment of renewed patriotism and an increased interest in Egyptian politics and society. Most of my interviewees described these first months as a time during which they mentally and psychologically lived in Egypt, even if they were physically in France. Thus, the events had a double effect. On the one hand, the political events since 2011 lead to an increased political mobilization among Egyptians abroad. On the other hand, they lead to a feeling of reunion with other Egyptians living in Paris, the demonstrations in Paris in January 2011 serving as a major space of mutual discovery.

A participant described this politicization as follows:

We did not really know each other before. (. . .) It was only from the 25th of January onwards that I started to look left and right to see what was happening, what the different belongings of Egyptians in France were. It was a factor of reunion. All these communities became involved in what happened in Egypt, in one way or the other. All, the Muslim Brothers, the Salafis, the Liberals, they all got involved. Suddenly, there was this conscience that we could not just let things happen in Egypt like that.

Another respondent especially stressed the role of the eighteen days in January 2011 as a moment of mutual discovery, a moment that was perceived as a deeply collective experience. The interviewee’s response makes it clear that these moments were lived and perceived as a time where the “we” became more important than the “I.”

I was all the time on the telephone or the internet. I remember, when I came back to Paris from a study trip, and I changed my mobile chip, I received a text message that there was a demonstration in front of the Egyptian consulate in Paris. I didn’t even change my clothes, but took my jacket and went to the Egyptian consulate... It started like this. I was all the time on Twitter, another person was on al-Jazeera, one on France 24, another one on BBC Arabic. There were [sic] news all the time, and you met people you didn’t even know they existed. During the eighteen days, we hardly ate, we hardly slept. One moment, we laughed, one moment we thought it would work, one moment it won’t.

This new feeling of collectivity is also emphasized in the following statement by one of the organizers of the Tamarrud campaign in Paris. She especially mentions the fact that even people who had never been involved in Egyptian community life in Paris before got in contact with each other and experienced a feeling of belonging together:

The revolution led to a feeling of closeness among Egyptians, not only in Egypt, but also here. The majority of people who have been here since ten or fifteen years and did not know any Egyptians, people who said that they never spent time with Egyptians—even people who said “stay away from Egyptians, they are annoying and too curious.” It was really strange. With the 25th of January, all Egyptians started to know each other. There were people who have been in France for fifteen years and they never met an Egyptian. Today, it’s really a friendship, it changed. I really have the feeling that it brought people together, it’s crazy.

Social movement scholars emphasize the significance of social context and physical space in the construction of collective identity. They agree that the collectivization of identity is an essential part of activism.15 As Rita Stephan pointed out, one essential question in this respect is how individual members identify themselves.16 Most of the female activists I interviewed emphasized that women were part of this new sense of collectivity and were important and active actors in the political struggle going on. One activist explains this phenomenon as follows:

I think the mobilization of women in the revolution is similar to other contexts. I believe that women are in general more active, but they are not necessarily looking for recognition. They are not as visible, but that does not mean that they don’t participate and even participate more. Because on the ground, there are not only men and women are attacked more brutally than men. (. . .) We are not numerous, but we are very active.

The revolution as a moment of renegotiating identity

This experience of collectivity is closely linked to questions of identity and a search for belonging. I argue that in a diasporic context, revolutions and important political events in people’s country of origin can lead to a renegotiation of one’s identity. One very important finding of my interviews with activists in Paris was that the revolutionary processes challenged and altered the perception of their identity. My interview partners narrated these moments of political upheaval as a time where their identity was renegotiated; their relation to France and Western society, on the one hand, and to Egypt and the Middle East, on the other. Universally, all activists emphasized that the revolution made them feel more “Egyptian;” a concept that was seen during the revolution to comprise multiple meanings. Some activists described that the political events made them feel “Egyptian” even if they did not necessarily feel so before 2011. For instance, one respondent told me that before 2011, she neither felt at home in Sweden where she grew up, nor in Egypt, where one of her parents was from. She felt alien in Egypt and had the feeling that nobody in Egypt resembled her in her way of thinking. She had the feeling that she did not “fit in” in any of these two countries. However, with the revolution in 2011, this fact changed considerably:

My mother told me. . . that we need the revolution more than the revolution needs us. I don’t know if this is true for people in Egypt, I can only talk about myself. . . Before the revolution, I felt. . . that I don’t fit. Sometimes, I didn’t want to go to Egypt because I didn’t fit. . . I was different. After the revolution, I can talk in poetic terms, it was like an open flower, you saw so many things in it, so many colors. Which we didn’t know. It took me some time to understand that I fit in and all people fit in because there is not only one way to be in Egypt, there are millions of ways to be in Egypt and they are all crazy (laughs) and it’s good that I am crazy.

The realization of Egypt’s diversity helped her to accept her own multilayered identity. It made her want to take part in this social movement and simultaneously reassured the Egyptian side of her identity. The participation in the political protest in 2011 and afterwards thus served as a rediscovery of her own identity and was a reason to identify with Egypt which was suddenly perceived as embracing different ways of thinking. The following comment by another activist underlines this feeling as well:

I think that the revolution has helped me in the perception of myself. Today, the fight of one part of the Egyptian population is about the recognition of diversity. So, I do not have to adapt to a certain archetypical Egyptian model. No, we are different, and that’s something that we have to defend and this, in some way, comforted me.

The revolution also allowed activists to “make peace”—in a certain way—with their Middle Eastern origin. One French-born young activist whose parents are both Egyptian talks in her interview about a feeling of pride which was given back to her through the revolution:

There is a feeling of pride that was given back to us. When your country goes through a phase like that, it is very difficult afterwards to continue with the society you live in just as before.

This sentiment was voiced by numerous other interviewees. They emphasized that the revolution gave them back a pride in their Egyptian origin, in a Middle East that had been for a long-time perceived as monolithic by Western public opinion and as democratically unable to change.

As Odmalm argues, the question of identification and its potential importance for political participation has been hinted at in a number of academic texts, but has been rarely studied systematically. He introduces the concept of identification as the missing link between literature on migration and identity and migration and political participation.17 My data indicates that the Arab Spring revolution in 2011 served as a moment of renewed self-identification with Egypt for Egyptians living abroad affecting their political behaviour deeply.

Characteristics of female transnational activists in Paris

Interestingly, female transnational activists in Paris share certain common characteristics, regardless of their political opinion. The majority of these women are well educated, well connected, speak several languages and lived in different countries. Most of them were already socially or politically engaged in some way or the other before the revolution. They are mostly professionally successful women. However, they differ in their age and their migration history. In regards to the socio-professional background of these activists, Mounira Charrad has already shown for Tunisian feminism that female activists are typically professional women working in academia, medicine, law and journalism.18 This also seems to be true for female activists in the (post-)revolutionary process in Egypt.

Hanna, a thirty-seven-year-old researcher, grew up in Egypt until she was sixteen and studied in Sweden, Norway and the United States before coming to France to work. Before 2011, she participated politically for issues such as racism in Norway, the Palestinian question, the war in Iraq and anti-globalization protests. In 2011, she became part of the Association of the 25th of January Paris and later participated in the Collective Voices of Egypt.

Marie-Ange was twenty-eight years at the time of our interview and was born in Paris. She described herself as Franco-Egyptian and just finished her studies in European Studies. She sees her professional future in educational or cultural projects connecting the two shores of the Mediterranean. She described herself as a very mobile and independently thinking person who travelled through Egypt by herself. She helped to organize the Tamarrud campaign in Paris and is part of the Collective Voices of Egypt.

Myra was born in 1955, holds a PhD in biophysics and is a clinical research consultant in Paris. She has been living in Paris for twenty-seven years where she undertook some of her studies, but also lived in London for several years. She is active in two NGOs, France-Egypt, which organizes conferences on contemporary and ancient Egyptian culture and Mared, an association campaigning for secularism in Egypt.

Shahinaz is somehow an exception to other interviewed female activists. Born in Alexandria in 1979, she lived in Egypt until 2010 and was already extremely politically active before 2011 as part of the Egyptian blogging scene and a member of Kifaya. She mainly blogs about her concerns with the lack of freedom of expression in the Middle East. As an activist, she has volunteered in NGOs and other civil society organizations in Egypt to encourage the formation of coalitions among human rights organizations. She moved to France because of family pressures she experienced as a single and independent female activist living alone in Egypt. In Paris, she is now working as an engineer for a French company and is one of the most visible faces in mobilizations in Paris. She has joined the Dustur party in 2012 and is campaigning for it in France.

The last two female activists I interviewed represented another type of activists. They participated in demonstrations in favor of the return of Muhammad Morsy after the events in the summer of 2013. Like other female activists, both of them are well educated, very eloquent and have very precise ideas about their political claims. They have both grown up in France and emphasized Islam as an essential element of their identity. One of them, the eighteen-year-old medical student Iman, was one of the main voices of the National Alliance to Support Democracy in Egypt (CODE) during demonstrations after July 2013. The twenty-three-year-old student Ikram, who has no Egyptian origins, is an activist in the pro-Palestinian Collective Cheikh Yassine, and participated as such in the “anti-coup” demonstrations. She defined herself as a Muslim activist and explains her participation in the CODE movement by the fact that the struggle going on in Egypt is similar to conflicts in other Muslim countries.

My findings parallel already existing research that indicates that, contrary to the classic view of assimilation theory, transnational political activities are not the refuge of marginalized or poorly educated immigrants. On the contrary, transnational activists are usually better educated than most of their compatriots, better connected, speak more languages and travel more often.19 Most of them do not begin their careers at the international level, but start engaging politically on the domestic level, and often return to their domestic activities after their transnational experience.

A FRAGMENTED AND GENDERED TRANSNATIONAL POLITICIZATION

The revolutionary events since 2011 have not only made ideological differences visible and created political divisions in Egypt, but also among Egyptians living abroad. To a certain extent, political developments in Egypt have been mirrored in Paris. After a first rapprochement during the eighteen days of the revolution in 2011 and a phase of increased political and civic participation, organizations were founded that followed the logics of respective organizations in Egypt, sometimes even carrying the same names. The Association des Jeunes du 25 Janvier was founded in the aftermath of the revolution, wanting to represent the “revolutionary” Egyptian youth abroad aiming at continuing their activities after the depart of Mubarak on 11 February 2011. This group had internal conflicts and divided later into two separate associations: Association du 25 Janvier Paris and Association du 25 Janvier France. Later, the April 6 France Movement started, representing the April 6 Movement in Egypt in France. Also, the Tamarrud Campaign in Egypt had a counterpart in Paris, organized by different activists. Finally, after the overthrow of Morsy’s presidency in July 2013, similar to Egypt, a group emerged supporting the return of Mohammed Morsy to the political scene, the National Alliance to Support Democracy (at-Taḥāluf al-Waṭanī li-Daʿm ash-Sharʿiyya). Political divisions already became apparent after the presidential elections in 2012, but increased highly after 30 June 2013 polarizing Egyptian social fields into two main camps, the dividing line crystallized around the terms “inqilāb” (coup) and “ath-thawra ath-thāniya” (second revolution), thus around the question of how the events on 3 July 2013 should be interpreted.

In general, women were less visible than men in mobilizations in Paris, offline and online. Nevertheless, women activists do exist in Egyptian transnational political networks and those who do exist are very active. Especially, social media has become a space for women to participate in discussions and actions taking place in Paris. Research on female cyberactivism has shown that cyberspace has been used as an instrument for Arab women’s activism for over a decade to discover, gain and discuss information, find kindred spirits, chat and participate in debates.20 Hawthorne and Klein have defined cyberactivism as “the act of using the internet to advance a political cause that is difficult to advance offline. . . to create intellectually and emotionally compelling digital artefacts that tell stories of injustice, interpret history, and advocate for particular political outcomes.”21

However, a series of challenges limit Arab women’s activism in cyberspace. Rita Stephan sees the low Internet penetration and internet restrictions in certain areas in the Middle East, combined with high female illiteracy rates and a patriarchal cultural discourse that inhibits women’s free access to the internet as the main limitations.22 This is exemplified by the fact that in the Middle East only a third of the Facebook users are female, while on a global level, half of all users are women.23 The outburst of the Arab Spring drew greater attention to women’s cyberactivism in countries such as Tunisia and Egypt where women turned to the Internet as a means of protest. In Egypt, during the revolution, both, men and women used the cyberspace to act as intermediaries between the world and mainstream media and delivered various eyewitness sources. The well-known activist Esraa Abdel Fattah known as the “Facebook girl” became famous for using Facebook to launch the April 6 movement.24

How are these dynamics now reproduced in a migration context and Egyptian communities in Paris, in particular? In general, the expansion of social media in the Arab World has been a huge impetus for its communities abroad to follow social and political processes in their country of origin, without necessarily having close personal ties to networks. In the case of transnational mobilizations in Paris, all of the studied networks relied on Facebook as a mobilization tool, whether as a tool to keep people informed about demonstrations, attract new members, or discuss political issues in specific, more closed subgroups created for this matter. Especially for small grassroots groups with little financial and organizational resources, Facebook was extremely useful to mobilize and organize support.

In general, we can say that the tendency of less female participation in cyberspace witnessed in the Middle East is also reproduced in social media profiles of Egyptian political networks in Paris. Nevertheless, the following analysis of Facebook networks shows that during the last three years, women clusters and female friendship networks have appeared in social media. Women participate heavily; however, they are rarely the most active discussion leaders.

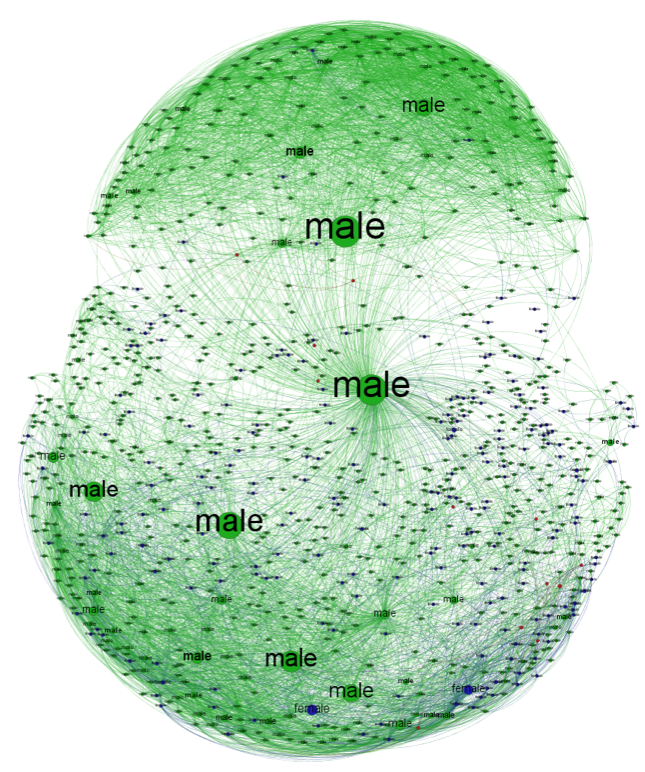

The group “The official page of the association of the youth of January 25 in Paris” had 967 members at the time of writing and is mainly divided into two main friendship circles (above and below) with one central member connecting these two groups. 220 out of the 967 members are women (blue), thus representing roughly a quarter (22.54 percent) of users. However, the best connected and most active members of the group (size of nodes) are male (green). The size of the node corresponds to the degree of connectedness within the network. Most of the friendship network is male dominated except for a small, female network within one of the two big friendship networks. Female members are less active and not as well connected.

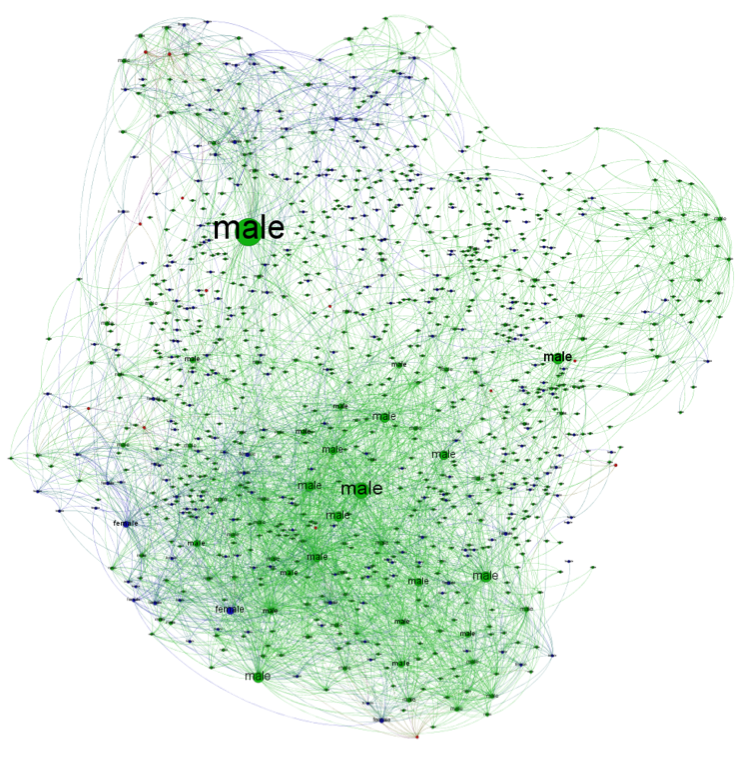

“Youth of 25 January in France” is an association which developed out of the original organization “Youth of 25 January Paris”. At the time of writing, the group had 1,026 members and was built up by three main friendship networks (of which one is much better interconnected than the other two). 247 of the 1026 users were female, representing 24.1 percent of all users. As in the first example, the whole network is mainly male dominated (green) and the best-connected members are male. However, smaller female networks can also be witnessed.

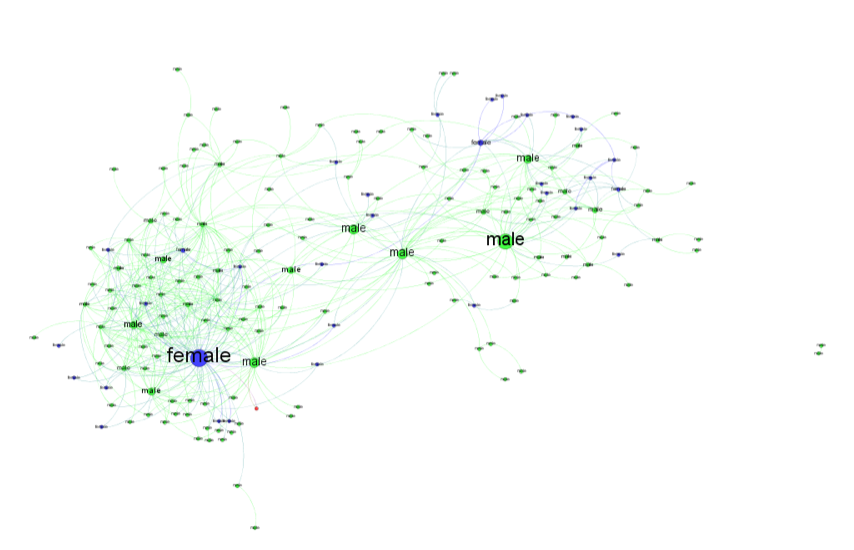

The group “The Movement of April 6 France” is much smaller than the first two examples with 234 members at the time of writing. The main network is built by two friendship circles. Out of its 234 members, 50 are female, corresponding to 21.37 percent of all users. Even if the majority of the best-connected users are male (green), in this network we can see one very active and well connected female member (blue).

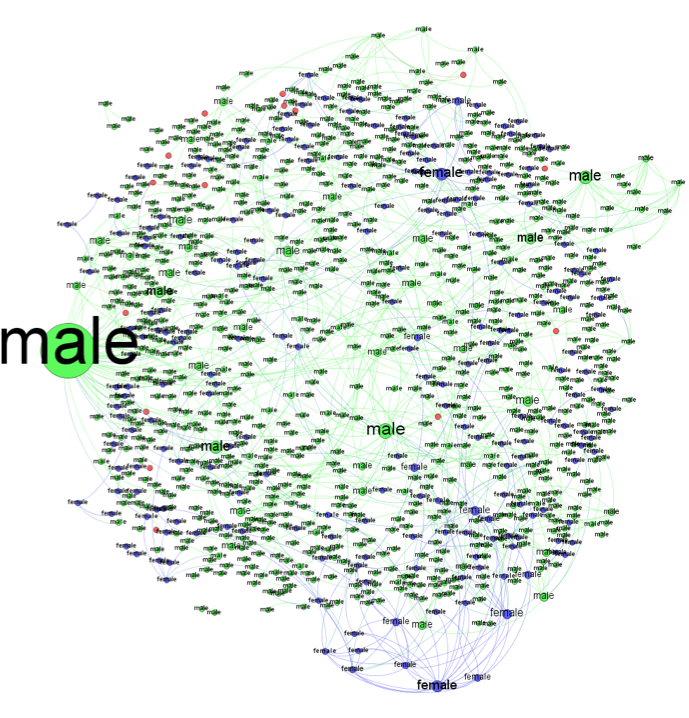

The Facebook page “The National Alliance to Support Legitimacy France” was used at the time of writing by 1,014 users. It is mainly formed by one big community that is strongly interlinked. 222 of its users are female, corresponding to 21.89 percent. As in the other examples, the most active and best-connected commentators are male (green), dominated by the administrator of the page. Nevertheless, two bigger female communities are visualized in the map and several well-connected female users are present in the networks competing in their level of activism with male users.

In summary, women’s participation in these virtual spaces can be viewed as less numerous and less visible compared to their male counterparts. The participation of women lays around 20–25 percent.

CHALLENGES FOR TRANSNATIONAL FEMALE ACTIVISTS: MARGINALIZATION AND FRAGMENTATION

As I have shown above, women are less numerous and less visible in transnational mobilizations in Paris trying to influence (post-) revolution in Egypt. The important question thus remains: Why is this the case?

Most of the major theories of incorporation devote almost no attention to gender while existing studies on transnational migrant politics tend to portray an image of very little participation, or none at all, by women.25 For instance, studies of Latino migrant populations in the US suggest that men usually dominate political activities involving the country of origin, especially the more institutionalized ones, while women tend to participate less and focus more on conditions in the receiving nation.26

In the following pages, I show how three factors influence women’s participation in Egyptian transnational politics in Paris: the gendered character of Egyptian migration to France itself; inner fragmentation and politicization among women, and thirdly; their own definition of politics.

A male dominated migration

The gendered character of Egyptian migration to France and patriarchal structures characterizing Egyptian transnational social fields in Paris play an essential role in the marginalization of women within these political networks.

Egyptians started to become active emigrants in the early sixties.27 Historically, Egypt was a land of immigrants, not emigrants. However today, emigration has become an omnipresent social phenomenon discussed in popular culture, such as Iqrā il-khabar (Read the news) by Masār Igbārī, films (Black Honey or ʿAsal Iswid by Khālid Marʿī) and literature, such as Safīnat Nūḥ by Khālid al-Khamīsī. Almost every Egyptian family nowadays has a member of its extended family living abroad. Over the last four decades, two distinct destination regions have emerged for Egyptian migrants: Arab Gulf countries and the industrialized countries of the West. Egyptian emigrants have been moving to the countries of the Arab Gulf mainly on the basis of temporary work contracts, normally without the prospect of permanent stay or right to citizenship privileges. However, since the 1960s, growing numbers have been also migrating to Europe, North America and Australia with the intention of staying permanently in these destination countries.28

Two waves of Egyptian migration to France can be distinguished. From the Suez Crisis in 1956 onwards, a rather small stream of Egyptians left Egypt in the direction of France. The majority of these migrants were either middle or upper class Egyptians who left Egypt because of Nasser’s nationalization programs at the beginning of the 1960s, followed by political opponents, Egyptian Jews and a—mostly Coptic—educational elite who migrated to France to continue their academic education.29 Today, this first migration stream has formed a second generation, but represents only about 10% of the total Egyptian community in France.30 Slowly, with the economic problems emerging in Egypt in the beginning of the 1970s the migration profile has changed considerably. The second—and much more significant— migration to Paris (and France) started in the second half of the 1970s31 and intensified in the 1980s when temporary labor migration to the Arab oil-producing countries declined as a result of economic and political developments in the Middle East.32 Reem Saad’s fieldwork on migration networks among Egyptian workers in Paris shows that new migration patterns have been set up, characterized by close networks and particular emigration regions in Egypt, stemming mostly from a limited number of villages and towns in the central Nile Delta, such as Mīt Badr Ḥalāwa in particular, but also Mīt Ḥabīb, Maḥallat Ziyād, and Banā Abū Ṣīr.33

Unlike the first wave of migration, this type of migration was often characterized as male labor migration. European countries have made legal migration more and more difficult in the last years. Because of that, France is experiencing a higher level of illegal migration, including Egyptian migrants. Most Egyptian labor migrants find employment in construction, the weekly food markets and restaurants through close-knit networks. The majority of these migrants are single men or have left their families back in Egypt and often live in all-male accommodations.34 Men thus often outnumber women in the political networks described above, as the following statement illustrates:

And here. . . it’s a problem of the type of migration, it’s labor migration and there are more men, it’s not because women stay in their homes, it’s because these men have no women (laughs). We are not many, but we are very active. It is just because we are in France. I don’t know how it is in other countries where there are more women than men, but here it is really because of the type of migration.

Inner fragmentation and politicization: Different versions of femininity and activism

Secondly,—as Stephan has shown—in the diaspora, fragmentation and politicization among women constitute a second challenge to women’s activism.35 Johansson-Nogués has argued that in social contexts characterized by social upheaval concepts of gender and sexuality tend to become destabilized. She uses Connell’s gender binary model (1987) of “hegemonic masculinity” (a privileged or culturally dominant type of masculinity) and a varied set of subordinated masculinities and femininities, to argue that when the former authoritarian regime in Egypt fell, the hegemonic masculinity that the regime had portrayed and reproduced, was toppled. 36 In the following political vacuum, different competing groups emerged offering each their own particular version of masculinities and femininities.

Transnational female activists I interviewed in Paris were internally fragmented in the question which place religion and Islam should play in their activism and its role in society. Shahnaz Khan’s article on Muslim women in Canada has described women’s translations and negotiations of Islam in minority diasporic communities in the First Wolds and has shown that in a diasporic setting the “grounding as a muslim [sic] is significantly more fragile than the women’s “home” countries.37 She emphasizes that “the Muslim community” is often assumed to be a single, monolithic religious community with no real understanding of progressive engagement with religion or any appreciation of feminist positions among Muslim women.38 The interviews I lead with activist women in Paris, their perceptions and negotiations of Islam and modernity, demonstrated on the one hand a large spectrum of opinions on femininity and their vision of activism as a woman and mirrored the fragmented public debate on Muslim (and Arab) women in the Middle East. Secondly, I argue that in a diasporic context today, the debate on Muslim women has become particularly sensitive and difficult. Some Arab-American scholars, like Naber, have reported from their personal experiences about the politicization and fragmentation they face as Arab women activists in the US,39 while others even speak about the politicization of Arab-American feminists who transplant political cleavages from the Arab world to the United States.40

It is very difficult to label the visions and negotiations of the women I interviewed and I somewhat prefer to restrain from doing so. Also, Evelyn Shakir’s book Bint Arab about Arab women immigrants in the US shows how women’s identity negotiations defy essentialized notions of “Arab” and/or “Muslim” identity.41 What can be said is that women I interviewed located themselves somewhere between two oppositional poles for gender justice present in the Arab world today: Riham Bahi has distinguished between two oppositional discourses mobilized for gender justice in the Arab World today, a “secular feminism” and an “Islamic/Islamist feminism” while she employs the terms Islamic/Islamist interchangeably and broadly to mean anything pertaining to Islam.42

Arab feminism was born during the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the emergence of Arab nationalism, in a highly complex context and—as Nawar al-Hassan Golley has put it—“out of the struggle between the dying, traditional, religious, feudal Ottoman way of life and the rising, modern, secular, capitalist European ways of life.”43 First nineteenth century reformers, such as Ahmad Fares el-Shidyak, Rifaa Rari al-Tahtawi, and Muhammad Abdu, emphasized especially the right to education for women. In literature on feminism in the Muslim (and Arab) World, scholars have often made a distinction between Muslim and Islamist feminism. Muslim feminism, incarnated by women such as Amina Wadud or Fatima Mernissi, affirms the equality of men and women under Islam by challenging and refuting traditional patriarchal readings of the Qur’an and the Hadith.44 The rise of Islamic women’s movements throughout the Arab world has further challenged secular assumptions of feminism by focusing primarily on progressive readings of Islamic texts to argue for a more egalitarian Islamic tradition than enhances women’s rights. Islamism emerged during the anti-colonial struggle of the Arab World during the early-to-mid twentieth century and carries until today strong anti-Western sentiments and an emphasis on the struggle against Western influences. Islamist feminists such as the Egyptian Zaynab al-Ghazali or the Moroccan Nadine Yassine emphasize the distinction to Western feminism and see Western feminism as an ideological vehicle for the differentiation of the public and private spheres, seeking to restrict God exclusively to the latter, as the following interview with Nadine Yassine shows:

Mine is not the feminism of Simone de Beauvoir, the Western style feminism. . . The West got rid of the idea of God, at least in the public sphere. It endeavors are purely materialistic. They thus automatically excluded any idea of spirituality to return to God. My struggle, on the other hand, is essentially spiritual, not a struggle between men and women for material entitlements.45

Rather than conceiving feminism as a single or coherent doctrine, I understand it as a “highly charged field of competing narratives about the nature and consequences of gender identities.” It is somewhat difficult to classify the women activists I interviewed in the above-mentioned categories, but what I observed is that these discourses played an important role in their activism and self-understanding as women, even if they did not label themselves as neither secular, nor Muslim or Islamist feminist. Their visions especially shed light on their multiple approaches to Islam and the question which role Islam should play in society. One main cleavage was the question of religion in the public space: While some women rejected religion in the public sphere, other emphasized Islam’s public role, the public role of Muslim women in this context, and in general, Islam as an essential part of identity. What I witnessed in Paris is that for groups like The National Alliance to Support Legitimacy France—and their subgroup Women Against the Coup mobilizing for the return of Morsy after 30 June 2013—Islam and religiosity are ever present and important parts of their activism.

For me, it is a lot about the Palestinian question, but at the same time this struggle makes us also sensitive to everything that is around us, to our condition of Muslim militants, of the youth also. It is all that which we try to translate into a militant fight. (. . .) What I learn from Egyptians, from all Arabs is that they will make their way without the so-called free people of the world. (. . .) Today, values are over there, they are not here anymore. You can see that. Last Saturday during the demonstration, there were people who passed and who said “again the Islamists, again the Arabs.” (. . .) Here in the Occident, people are less attached to values, it is over there where things are decided. It’s them who carry the values. . . that’s at least what I think. Honestly, I do not worry about people there; I worry more about people here.

On the other end of the spectrum, religiosity is somewhat absent in the narration of liberal activists who identify with secular feminism:

Mosques. . . Hmmm, I do not know them, but they have been so destructive that I do not have confidence in them. I prefer that they remain outside of everything. (. . .) For me. . . I like my religion, I am Muslim, I assert that I am Muslim, but I am outraged that they use this religion to send us back to the Middle Ages. Here, I do not agree. I do not go to mosques.

The liberal activist and Kifaya supporter Shahinaz describes her ideological differences with female Islamist activists in Egypt as follows:

I participated with the Islamists in. . . things for Palestine. It’s funny, they do things for Palestine all the time, not for Egypt. I have to say that. But there were things I believed in, so I participated with them. It was funny, I was the only unveiled woman who participated in a demonstration with the Islamists and who walked in front, with the guys. My friends at university laughed at me all the time (. . .). But the Islamist girls, they thought that I was brilliant, they tried to convince me to ally with them during a whole year. They thought that I was great, but that I committed sins because I went out with boys. And because I said slogans that you shouldn’t say. And because the voice of a woman is cawra [intimate part of her body]. They tried really hard (laughs).

Marginalized by definition: A broader notion of politics and political participation

Thirdly, I argue that women are less visible because female activists in their majority have a broader notion of political participation and do not necessarily define themselves as “political activists.” Michelle Kondo’s research on gender and political participation reveals that activists challenge the traditional notions of political motivations and recognized a broader range of motivations for political participation among women.46 The personal often acted as a starting point for the political for her interviewees, thus blurring the traditional boundary of public and private often postulated in political participation.47 Numerous studies have shown that immigrant women are providing community organizing leadership within receiving countries.48 Thus, Kondo argues that a broader notion of political incorporation including informal political activity is necessary to understand women’s political activism thoroughly.49 Consequently, when informal political activity is included, levels of political participation among women increased significantly. This fact was also reflected in interviews I conducted with female activists in Paris when I asked them about why they participate politically and if they perceived themselves as political human beings.

Most respondents mentioned very personal reasons for their political activism, such as wanting to support family members who are active in a political group or discrimination they experienced or witnessed in Egypt. Most interviewees emphasized their wish to create a more equal and just society as the main reason for their political involvement. They heavily emphasized the social character of their actions, and somewhat downplayed their political character. In the logical conclusion of that argument, they did not necessarily define themselves as political activists, even if by definition they are. The following statement illustrates this tendency very well:

No, it’s only events which. . .I am a person who has moral and social principles. I was never a person who was interested in politics as such (. . .). Above all, I have no political ambition whatsoever. That’s the difference. I want to make my voice heard for a humanitarian goal.

Nawar al-Hassan Golley has argued that the basic divide by social scientists into a “public” and “private” sphere does not capture the social reality of Arab women and the multiplicity of roles that they play in their societies. She argues that in Arab countries—where the family performs obvious political, economic and cultural functions— there is no sense in drawing a hard line between the “public” and the ”private” sphere because women often affect public life heavily through family structures. She argues that roles Arab women play might seem to have only social dimensions at first, but they can also greatly affect male politics.50

CONCLUSION

This paper sheds light on the ways in which Egyptian women engaged in transnational mobilizations in Paris, how they experienced and lived these moments as they took part in their struggle. The revolutionary process in Egypt in 2011 lead to a massive politicization of Egyptians who had been disillusioned by politics for a long time. The revolution was lived by many Egyptians—both in Egypt and its diasporic communities—as a deeply collective experience and altered their relationships to Egyptian politics and society. Women were part of the political struggle and participated on a significant scale in the public sphere and in the cyberspace during the uprisings.

Through a discussion on transnational political networks in Paris and the politicization of Egyptian social fields during the revolutionary processes in Egypt, I showed how political events in Egypt can, and have affected life among members of the Egyptian diaspora. The revolutionary upheavals between 2011 and 2013 were a trigger for the emergence of a new sense of collectivity that included women. Nevertheless, transnational mobilizations in Paris were male dominated. Women participated in demonstrations, political networks and cyberspace to a significant extent, but were less visible and less numerous than men. Despite their smaller numbers these women activists were typically neither marginalized nor poorly educated immigrants, but were educationally, socially and economically privileged.

Women in a diasporic context face several obstacles in their transnational political participation. These derive from various things such as the characteristics of the respective migration itself, inner fragmentation among women, but also the activists’ own understandings of political participation. In Paris, mobilizations were, and continue to be, heavily influenced by the predominantly male character of Egyptian migration to France and the patriarchal migration networks that engender and facilitate it. Recent Egyptian migration to France is predominantly male, and often irregular, labor migration. Already marginalized by their minimal numbers, women are further fragmented by their vision of activism and femininity dividing them in their interpretation of the role religion should play in their activism. Furthermore, women often see their activism in more social terms than political, emphasizing humanitarian and global justice rather than their political objectives.

Elisabeth Johansson-Nogués has explained women’s lack of influence over the direction of the current state-building projects and the current insecurities in Egypt by a discussion of discursive femininities and masculinities in Egypt: She argues that in 2011, with the fall of the regime of Moubarak, the hegemonic masculinity of the former authoritarian regime was toppled. With the rise of the Islamist party, a counter-masculinity emerged, engaged in discursively marking its difference from the prior hegemonic masculinity pictured as “alien” and “imported from the West.” In this context, women whose participation was crucial for the delegitimization of the regimes and their subsequent fall were subsequently being othered by their previous co-revolutionaries as though they were a mere straightforward extension of the former regime. Johansson-Nogués explains that this has led to a decided leadership vacuum in women’s social movements developments Tunisia, Egypt & Libya.51 Only future developments in the region will show how women’s participation in Egyptian politics will turn out to be and how visions of femininity will shape their actions, especially after the elections in May 2014.

NOTES

Maha Abdelrahman, “The Transnational and the Local: Egyptian Activists and Transnational Protest Networks,“ British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 38/3 (2011): 407–24; Zuleykha Asadova, Exploring the Impact of Transnational Civil Society on the Egyptian Uprising: Has the Transnational Engagement Been a Success Story? Master Thesis (Central European University, 2012); Laila El Baradei, Dina Wafa, and Nashwa Ghoneim, “Assessing the Voting Experience of Egyptians Abroad: Post the January 25 Revolution,“ Journal of US-China Public Administration 9/11 (2012): 1223–43; Dina Abdelfattah, “Impact of Arab Revolts on Migration“ [online], CARIM Analytic and Synthetic Notes 68, accessed 18 December 2013, http://www.carim.org/public/workarea/home/Website%20information/Literature/asn2011%20en%2068.pdf; Marta Severo, Eleonora Zuolo, “Egyptian e-diaspora: Migrant websites without a network?, “ Social Science Information 51 (2012): 521–33.↩︎

Abdelfattah, “Impact of Arab Revolts,” 4.↩︎

Ibid., 8.↩︎

Ibid., 9.↩︎

Charlie Cabot, “Egyptian diaspora get involved in Tahrir Square Foundation,” Daily News, 28 July 2011,

http://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2011/07/28/egyptian-diaspora-get-involved-in-tahrir-square-foundation/.↩︎Abdelfattah, Impact of Arab Revolts, 9.↩︎

Elisabeth Johansson-Nogués, “Gendering the Arab Spring? Rights and (in)security of Tunisian, Egyptian and Libyan women,” Security Dialog 44/5–6 (2013): 393–94.↩︎

Christina Green, Our Separate Ways: Women and the Black Freedom Movement in Durham (North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).↩︎

Rita Stephan, “Creating Solidarity in Cyberspace: The Case of Arab Women’s Solidarity Association United,” Journal of Middle East Women's Studies 9/1 (2013): 84.↩︎

Stephan, Creating Solidarity in Cyberspace, 83.↩︎

Eva Østergaard-Nielsen, Transnational Politics. Turks and Kurds in Germany (London: Routledge, 2003), 15.↩︎

Gilles Pinson and Valérie Sala Pala, “Peut-on vraiment se passer de l’entretien en sociologie de l’action publiques,” Revue française de sciences politique 57 (2007): 581.↩︎

Richard Rogers, Digital Methods (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013), 2013.↩︎

Tommaso Venturini, “Great expectations: méthodes quali-quantitative et analyse des réseaux sociaux,” in Jean-Paul Fourmentraux, ed., L'Ère Post-Media. Humanités digitales et Cultures numériques, (Paris: Hermann, 2012), 39–51; Rogers, Digital Methods; Bernhard Rieder, “Studying Facebook via Data Extraction: The Netvizz Application,” in Proceedings of the3rd Annual ACM Web Science Conference, WebSci’13 (2013), 346–55.↩︎

Enrique Laraña, Hank Johnson, and Joseph Gusfield, New Social Movements: From Ideology to Identity (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994); Francesca Polletta and James Jasper, “Collective Identity and Social Movements,” Annual Review of Sociology 27 (2001): 283–305.↩︎

Stephan, Creating Solidarity in Cyberspace, 93.↩︎

Pontus Odmalm, Migration Policies and Political Participation. Inclusion or Intrusion in Western Europe? (Basingstoke–New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 221.↩︎

Mounira Charrad, “Policy Shifts: States, Islam and Gender in Tunisia, 1930s–1990s,“ Social Politics 4/2(1997): 284–319.↩︎

Sidney Tarrow, The New Transnational Activism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 43.↩︎

Susan Gavi, “The Wired Arab Woman,” Online Journalism Review, posted 44 November 1999, modified 4 April 2002, http://www.ojr.org/ojr/business/1017967013.php.↩︎

Susan Hawthorne and Renate Klein, “CyberFeminism: Introduction,” in Susanne Hawthorne and Renate Klein, eds., Cyberfeminism: Connectivity, Critique + Creativity (North Melobourn, Australia: Spinifex Press, 1999), 145.↩︎

Rita Stephan, “Cyberfeminism and its Political Implications for Women in the Arab World,” 28 August 2013, http://www.e-ir.info/2013/08/28/cyberfeminism-and-its-political-implications-for-women-in-the-arab-world/.↩︎

Dubai School of Government, “The Role of Social Media in Arab Women’s Empowerment,” Arab Social Media Report 1/3 (November 2011), http://www.arabsocialmediareport.com/UserManagement/PDF/ASMR%20Report%203.pdf.↩︎

Stephan, Cyberfeminism and its Political Implications.↩︎

Katharine M. Donato, Donna Gabaccia, Jennifer Holdaway et al., “A Glass Half Full? Gender in Migration Studies,” International Migration Review 40/1 (2006): 12, citing Alejandro Portes, Min Zhou, “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530 (1993): 74–96; Alejandro Portes and Rubén Rumbaut, Immigrant America. A Portrait (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996); R. Alba and V. Nee, Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003); F.D. Bean, G. Stevens, Americas Newcomers and the Dynamics of Diversity (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2003).↩︎

Goldring 2011; Guarnizo, Portes, & Haller 2003; Itzigsohn & Giourguli-Saudeco 2005; Jones-Correa 1998.↩︎

Nazih Ayubi, “The Egyptian ‘Brain Drain’: A Multidimensional Problem,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 15/4 (1983): 431.↩︎

Ayman Zohry and Priyanka Debnath, A Study on the Dynamics of the Egyptian Diaspora: Strengthening Development Linkages (Cairo: IOM, 2010), 15.↩︎

Isabelle Lafargue, Itinéraires et Stratégies Migratoires des Egyptiens vers la France, PhD Thesis (Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Paris, 2002), 311–13.↩︎

Interview Mahmoud Ismail, Egyptian Cultural Office in Paris, 12 March 2013.↩︎

Lafargue, Itinéraires et Stratégies, 316.↩︎

Detlef Müller-Mahn, “Transnational spaces and migrant networks: A case study of Egyptians in Paris,” NORD-SUD aktuell (2005): 29–30.↩︎

Reem Saad, “Egyptian Workers in Paris: Pilot Ethnography,” Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty (May 2005), http://www.dfid.gov.uk/r4d/Output/173792/Default.aspx.↩︎

Saad, Egyptian Workers in Paris, 5.↩︎

Stephan, Creating Solidarity in Cyberspace, 86.↩︎

Raewyn Connell, James Messerschmidt, “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept,“ Gender & Society 19/6 (2005): 829–59, cited in Johansson-Nogués, Gendering the Arab Spring, 396.↩︎

Shahnaz Khan, “Muslim Women: Negotiations in the Third Space,” Signs 23/2, 463.↩︎

Ibid., 463.↩︎

Nadine Naber, “Decolonizing Culture: Beyond Orientalist and Anti-Orientalist Feminisms,“ in Rabab Abdulhadi, Evelyn Alsultany, and Nadine Naber, eds., Arab and Arab American Feminisms: Gender, Violence and Belonging (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011), 88.↩︎

Stephan, Solidarity in Cyberspace, 87.↩︎

Evelyn Shakir, Bint Arab, Arab and Arab American Women in the United States (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1997).↩︎

Riham Bahi, “Islamic and Secular Feminisms: Two Discourses Mobilized for Gender Justice,” Contemporary Readings in Law and Social Justice 3/2 (2011): 114.↩︎

Nawar Al-Hassan Golley, “Is Feminism Relevant to Arab Women?,” Third World Quarterly 25/3 (2004): 529.↩︎

Halverson and Way, Islamist Feminism, 508–09.↩︎

Emmanuel Martinez, “Islamic Feminism,” Le Journal des Alternatives, 26 October 2008, http://journal.alternatives.ca/spip.php?article4173.↩︎

Michelle Kondo, “Influences of Gender and Race on Immigrant Political Participation: The Case of the Trusted Advocates,“ International Migration 50/5 (2012): 113–29.↩︎

Kondo, Influences of Gender, 114.↩︎

See Alejandro Lugo & Bill Maurer, eds., Gender Matters: Rereading Michelle Z. Rosaldo (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000), 117; Michael Jones-Correa, Between Two Nations: The Political Predicament of Latinos in New York City (New York: Cornell University Press, 1998).↩︎

Kondo, Influences of Gender, 114.↩︎

Al-Hassan Golley, Is Feminism Relevant to Arab Women, 526.↩︎

Johansson-Nogués, Gendering the Arab Spring, 404–05.↩︎