Sara Pekow

FROM FARM TO TABLE: THE FOODWAYS CONNECTION BETWEEN RURAL AND URBAN WOMEN IN SYRIA AFTER WORLD WAR I

Abstract

Syrian rural poor and urban women experienced the rupture of World War I in vastly different ways, but they were linked across class and region through the country’s foodways. Due to economic instability, more rural women were forced into agricultural labor. The food crops they produced were in turn served by women across the country to their families. Though their burden was not comparable to that of agricultural laborers, middle-class Syrian women were also faced with greater responsibilities in the postwar era. A new emphasis was placed on the centrality of the mother in the life of her children. Women were urged to refrain from pursuing employment and entertainment in the public sphere in favor of staying home, caring for children, and preparing family meals. The use of domestic help and wet nurses, which had been common among families of means, was discouraged. While men were viewed as the frontline force in building the modern nation and its economy, women’s domestic and paid labor became even more marginalized in the national narrative. It is by looking behind closed doors and at the production of food that women’s roles in nurturing the nation can be told.

INTRODUCTION: AN UNEASY PEACE

At the end of World War I, the population of Syria looked very different than it had in 1914. A devastating famine had wiped out hundreds of thousands in the Levant, scores of men who had been recruited in the Ottoman military’s seferberlik campaign had been killed, and tens of thousands of Armenians, mostly women and children, continued to stream in, fleeing ongoing violence in Anatolia. As four hundred years of Ottoman rule came to an abrupt end, new borders were drawn, interrupting trade routes and pastoralists’ mobility. With British support, Emir Faysal, son of Sharif Hussein of the Hijaz, was appointed Syrian ruler in October 1918. After less than two years, Britain withdrew its sponsorship of Faysal once it was no longer politically expedient, allowing the overthrow of his government by the French in July 1920. Violent skirmishes flared up during the early years of the French Mandate, culminating in 1925 in the Great Revolt, a two-year rebellion initiated by Druze agriculturalists in the Hawrani plains southeast of Damascus. The revolt then spread among urban nationalists across the country, until it was brutally repressed by French forces with aerial raids and the burning of villages, leading to mass internal displacement.

The upheaval of the war and its aftermath led to seismic shifts in the household, affecting women in particular. While still responsible for caring for their families, many women were forced to seek additional means of income as economic pressures mounted. As over 60 percent of laborers in Syria worked in agriculture, the vast majority in food crops, women’s paid labor often centered on some part of the food production chain. In this paper I will explore the challenges Syrian women faced after World War I in procuring and preparing food for consumption inside the home as well as their work with food as paid laborers. Not all of the changes that occurred in Syria during the interwar period can be attributed to World War I or the shift from Ottoman to French rule, and whatever transformations did occur did not appear abruptly. Some were part of a much longer process that can only be understood when analyzed alongside multiple variables and previous eras. As James Gelvin argues, the Mandate era does not represent a significant break with the past in terms of social and cultural history.1 However, both change and continuity can be observed even over the brief Mandate period when focusing on smaller sites of transformation in labor, consumption, and agriculture, which become apparent at the intersection of foodways and gender.

I argue that though the lives of rural poor women and urban women of means appear disparate, they were connected over spatial and class barriers by food. This article seeks not to juxtapose the lives of rural and urban Syrian women, but to bring forward their stories with food as the common denominator. Rural women labored over fields and crops that were in turn purchased, prepared, and served by women across Syria to their own families, or the families which they served as domestic employees. Elizabeth Thompson’s excellent Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal Privilege, and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon brings the lives of middle- and upper-class twentieth-century Syrian women into the historiography.2 While her contribution should not be overlooked, there remains a lacuna in secondary literature on the lives of Syrian rural and poor women after World War I. Despite a lack of primary sources pertaining to non-elite Syrian women, by reexamining traditional archival sources, newspapers, and memoirs, it is possible to put together a picture of the lives of these women, which will allow for a more complex reading of Syrian history.3 In the second section, I will look at how a new discourse surrounding food and domesticity emerged after the war, changing conceptions of taste and nourishment for urban families of the middle and upper classes, as well as how this related to notions of class and family.

REAPING WHAT SHE SOWS: WOMEN’S LABOR ON THE FARM

The decline of textile manufacturing in the nineteenth century led to a steep population drop in Syrian urban centers.4 The growing indebtedness in which many households found themselves as Syria was integrated into the world economy, alongside climatic and economic fluctuations, pushed many women into unrecorded and poorly paid agricultural labor.5

After World War I, textile handicrafts and manufacturing further deteriorated due in part to restrictive tariffs, the proliferation of artificial silk, and changing tastes. Women made up a significant part of the textile labor force and were particularly hard hit, as there were few other industries to which they could easily transfer;6 at the turn of the century, one-third of the textile workers in Damascus were female.7 In the city of Homs alone, about 25,000 men and women out of a total population of 65,000 lost their textile jobs during the 1920s.8 Some of the unemployed textile laborers in Homs and Hama found work on farms.9 The number of handlooms for cotton weaving in Aleppo dropped from 14,250 in 1913 to 700 in 1934.10 The Great Depression accelerated this decline; from 1930 to 1933, wages fell among handicraft and industrial workers in Syria from 10 to 30 percent, and in some cases up to 40 to 50 percent.11 The cost of necessary goods rose much faster than wages; in 1937, a worker would have to complete 48 days of labor to purchase the same amount of staple foods that would have only required 22.5 days of work in 1913.12

The shift in textile consumption was also felt among rural women. According to Thompson, the declining sales of home crafts led more peasant women into paid agricultural labor.13 Though textile work was certainly arduous, many women had done piecework at home, conducting their labor according to their own domestic schedules. When they moved into domestic labor outside the home or farm labor, they were at the mercy of supervisors, nature, and landowners while away from their homes and families, the needs of which would have to be met as soon as the women returned home.

The number of women working in agriculture fluctuated based on region and time period. According to official statistics, in 1921, over 120,000 women were employed in agriculture in southern Syria, which included the fertile plains of the Hawran. These women earned on average 20 piasters a day. The 193,500 male agricultural laborers in the same region earned an average of 35 piasters a day. In 1926, men’s salaries in southern Syria dipped slightly as did the number of them working in the fields, while the number of women working in agriculture grew to 171,000, and their salaries increased on average an additional 5 piasters. The increase in female agricultural labor in southern Syria in 1926 might have been a result of a large number of men in the Hawran taking up arms during the Great Revolt, or it may be due the decline of the number of children working in agriculture, which went from over 100,000 in 1921 to around 60,000 in 1926. It is unclear to what to attribute the decline in child agricultural labor in southern Syria, as the numbers working in industry fell only slightly, and the number of children working in agriculture elsewhere in the county remained static.

In the Aleppo region, approximately 20,000 women were officially employed as agricultural laborers in the early 1920s, earning 25 piasters per day.14 In 1921, 40,000 men worked in agriculture in Aleppo, earning 35 piasters per day. By 1926, the number of men with agricultural jobs in Aleppo had risen to 59,000, their wages dropping to 30 piasters, while the number of women in agriculture stayed the same along with their salaries. The number of women working in agriculture also remained constant in the Alawite State between 1922 and 1927 at 50,000, but the number of men employed fell from 80,000 in 1922 to 50,000 in 1927. Women’s salaries in the Alawite State went from 35 piasters a day to 25 over the same time period, while men’s earnings only decreased from 55 to 50 piasters.15 In August 1929, the price of the highest quality bread in Damascus cost 25 piasters per rotl (1.65 pounds), the amount of all or most of a farm laborer’s daily earnings.16

Women were rarely offered the longer-term contracts for agricultural labor which were provided to men in certain regions. Despite a smaller paycheck and less job security, day labor allowed women the flexibility to tend to the household and childbearing and child-rearing as necessary. As Margaret Meriwether has observed for late-nineteenth-century Aleppo, even women who did not do salaried work outside of the home likely saw their domestic duties increase as more and more men had to go to work as agricultural laborers for large landowners.17 After the war, the disenfranchisement of agricultural workers accelerated. A combination of agricultural, taxation, and land code policy under the French Mandate led to an increase in large landholdings and decrease in small farms, pushing farmers into sharecropping or wage labor away from home.18

FOOD PRODUCTION, PAID AND UNPAID

Food preparation was another field in which women could find salaried employment. In the Damascus region, during the late summer walnut harvest, men were hired to knock walnuts off the trees with poles, which would then be gathered by men, women, and children. Women were then hired in Damascus to crack and shell the nuts with rocks and hammers at low pay.19 In Aleppo, several hundred Armenian refugee women were employed each season to crack pistachios. They worked seated in rows on the floors of the warehouses delicately separating the nuts from the shells with pincers, earning 15 cents a day and up to 40 cents a day according to the number of nuts they cracked.20 Urban food industries hired few women laborers compared with textile and handicraft production. In Aleppo in 1926, 1870 men and 1470 children worked in flour mills, bakeries, conserves production, and candy making, and in 1927, these numbers rose to 2177 men and 1723 children. Whereas over 8,000 women worked in other industries in Aleppo in 1926, and over 11,000 in 1927, no women worked officially in food industries during those years.21 In Damascus, where there was a higher degree of semi-industrial and industrial food production, more women were hired. Half of the 40 workers at the Ahmad Abou Chaar candy-making business were women in 1935.22

In addition to the numbers of women officially working in agriculture listed above, countless women assisted their husbands in farm work without remuneration, as part of what scholars have labeled “the invisible economy.”23 In the 1930s in al-Quneitra in the southwest, men who were also small landowners and cultivators were hired to work on construction projects for the state. Mohammed Diyab al-Zahir, a resident of Nab‘a al-Sakhir, recalls that 300 men left the village every morning by car for work sites and returned home in the evening. In the absence of their husbands, the women of the village milked the cows and carried out the farm work.24 Women conducted labor on behalf of their husbands in other trades as well. In his study of the village of al-Sukhna, Albert de Boucheman notes that of the three car repair shops that opened in the desert region in the 1930s, two were run by women, which he believed occurred frequently as men diversified their incomes with new opportunities which arose with the diffusion of new technology and trade as agricultural income contracted.25

Female laborers did not have any legal protection in Syria until 1935, which was obtained thanks in part to the mobilization of women industrial workers.26 A 1927 Mandate report on labor stated there were no rules on the treatment of pregnant women, nor did a minimum age of employment for children exist.27 Under the 1935 law, women were to take a mandated rest of one hour after four consecutive hours on the job. Upon providing a medical certificate, pregnant women were permitted to be absent one month prior to delivery, and employers were forbidden from making women work for thirty days after delivery.28 It is unlikely that these laws were enforced for agricultural laborers.

Many tasks associated with animal husbandry and the handling of animal byproducts were divided according to gender. Women were responsible for poultry and could earn extra income by collecting and selling eggs to nearby villages or trading with a peddler.29 Herds that were taken through urban areas for milk sales were tended by men, but sedentary flocks were usually the domain of women.30 Women and girls in Tell Tuqan generally took advantage of the twice-daily milking times to socialize as they walked together to and from the flocks.31

FOOD PRESERVATION

Other than cheese production, which was usually a commercial venture, most dairy products in rural regions were prepared in the home. Refrigeration was rare, particularly in rural areas, so the preservation of dairy was a vital component of food preparation and women’s labor. In 1934, 138 refrigerators were imported into Syria and Lebanon, rising to 628 the following year.32 Outside of urban areas where cow milk was favored, most milk came from sheep and goats. Ewes only provide milk for two to three months, but if a herd’s pregnancies are spaced out, milk can be available for up to seven months from late fall to midsummer.33 The price of meat put regular consumption out of reach for most of the population, which made homemade fermented dairy products an essential part of the daily diet. Any milk that was not sold underwent a four-day preservation process conducted daily during milking season.

The day of milking, some fresh milk might have been consumed and the rest was slowly heated and left overnight, loosely covered, transforming into laban by morning. A staple in many Syrian dishes, laban can be kept for up to a month without refrigeration. On the third day after milking, butter was produced by placing laban thinned with water in a goatskin bag and rolling it around on the floor for an hour or so. In other areas, women were observed churning butter over a wooden tripod.34 Butter was either eaten fresh the day of production or converted into samn, clarified butter with a longer shelf life than fresh butter that was the preferred cooking fat in most Syrian kitchens. The liquid left over from butter churning, known locally as shanina and elsewhere in Syria as ayran, was consumed as a beverage.35 On the fourth day, kishk was produced by salting and cooking the remaining shanina and then drying it in a sack. When the contents of the sack had reached a paste-like consistency, it was removed and spread on a flat roof to bake in the sun.36 John Lewis Burckhardt observed very similar methods of kishk preparation in the 1820s, and the combining of cereal and dried sour milk can be traced back to the thirteenth century in the Levant.37 Kishk is made differently from region to region across the Middle East and parts of Europe, but preparation in Syria usually involves the addition of burghul (bulgur) or another grain prior to the drying process.38 According to Jamal al-Din al-Qasimi, who wrote his famous Qamus al-sina‘at al-shamiyya in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the wealthy prepared kishk with meat, and the poor made it with olive oil and onions, but the best kishk was enjoyed by those in the middle of the economic spectrum.39 Selling dairy products prepared at home was another way Syrian women earned additional income.40

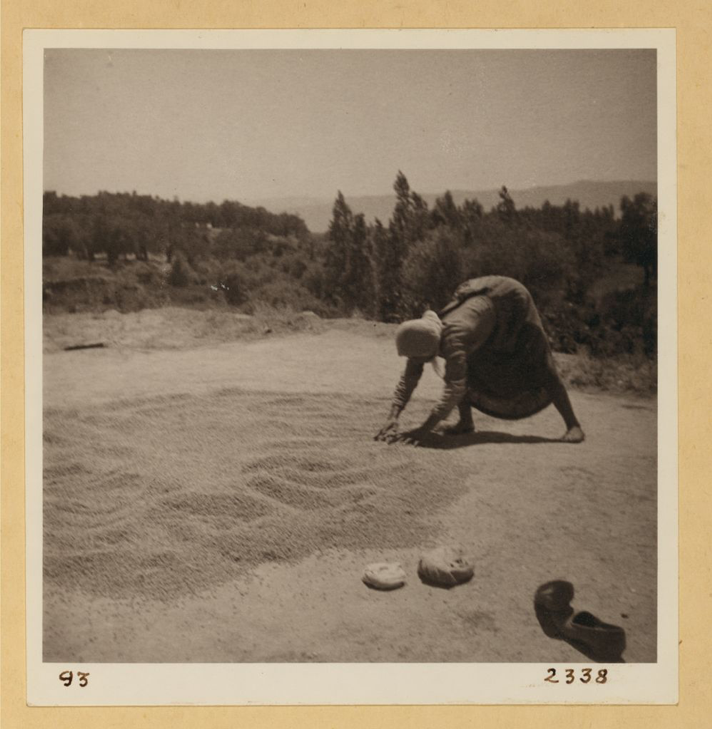

In addition to dairy products, it was necessary for women to preserve other seasonal foods for the winter, such as tomato paste, parboiled wheat and corn, and eggplant, squash, and red pepper, which were strung on the ceiling to dry. Outside of their makeshift homes over a decade after World War I in the refugee settlement at Kirik-Khan in the sanjak of Alexandretta, Armenian women hung garlands of red peppers to dry on the door alongside bands of bastorma, a meat sausage popular in Armenian cuisine.41 In some areas it was possible to send burghul to a nearby mill to be machine ground and cleaned, but other still prepared it at home during the interwar period. To prepare burghul at home, after sifting the chaff out with a sieve, the wheat is moistened with water and wet-milled on a stone mill, then spread out to dry on roofs or white sheets on the ground where it is separated from the bran by the wind before being graded with a sieve.42

Bread making was another time consuming and necessary labor of rural women, as well as some urban women. In some areas, women took turns baking bread in a community oven once a week.43 In Tell Tuqan, bread was prepared every three days, requiring about an hour of work each time. A nomadic bedouin woman named Meta in the Homs-Hama region described kneading dough in advance of her tribe’s departure, letting it rise for about an hour. When she was ready to bake the bread, Meta tossed a ball of dough from hand to hand until it was the right size for the saj, the domed iron griddle on which it was cooked over the fire.44 Pastoralist women in Tell Tuqan prepared their bread in the same way, but village women baked khubz tanur, which was also kneaded into large circles, against an oven wall instead of over a fire. This was considered a more prestigious method than the khubz saj; girls from pastoralist families often apprenticed informally under village women to learn how to make this bread to broaden their marriage prospects.45 In urban areas, bread could be purchased from bakeries, which usually only employed men. A 1938 film made in the Souk al-Hamidiyya shows a man kneading khubz saj and then placing it by hand in the mouth of a rounded clay stove which he fueled with straw. The thin, round bread was then sold outside of the tiny bakery.46

Among rural women’s other duties were preparing fuel, which in most of rural Syria consisted of dung cakes, and tending the fire for cooking, which could take up to two hours a day.47 In areas that relied on shared wells for water, women were usually responsible for water collection. In Qalamun in the mountains outside of Damascus, it could take more than an hour to descend to the water source and return. Wealthier families would pay to have their water transported by donkey, but the poorer families lived furthest from sources of water and had to go on foot.48 One study found that rural consumption of water to be about a sixth of urban consumption because of the difficulty in obtaining it.49

CITY LIVING: FROM FARM TO TABLE

As different as the lives of urban elite women were than their rural counterparts, they too were expected to dedicate themselves to the nourishment of their families. Even for the minority of women of means who could afford domestic help, there were new pressures being placed on middle- and upper-class women after the war. In the pages of the Damascus women’s periodical, Majallat al-mar’a, mothers were cautioned not to trust a servant to nourish her child, as she would not be concerned about “giving him cold milk or unclean fruit and cannot afford to spend a half hour hand-feeding him a number of times a day or teach him to feed himself.”50 A column in another women’s magazine warned mothers against allowing others to instill morals in her children: “Of the habits that must be completely done away with is handing children off to servants, particularly servants in our country who are remote from culture and child rearing.”51 A similar discourse had transpired in early twentieth-century Egypt, as Omnia Shakry has found, with the spread of tarbiyya literature, which solidified the boundaries of family, class, and domestic space, and vilified servants for bringing bad character into the home.52

As Sara Pursley has written about Iraq, the family in the Middle East was being redefined in the twentieth century as a nuclear family, a unit in which perceived outsiders such as domestic servants and wet-nurses were no longer acceptable.53 Syrian historian Abdullah Hanna describes the two types of families as al-abawiyya (paternal) and al-zawjiyya (marital).54 Extended kinship compounds of the past, along with the helping hands of female relatives, were being abandoned for single-family residences. This did not translate into a complete renunciation of paid labor in Syrian homes, but middle-class women in particular were frequently reminded via the press and classroom that their job was to keep a hygienic home, feed their families, and teach their children to become good citizens. In fact, based on labor statistics collected by the Mandate, the number of both male and female domestic laborers from the Alawite state and the sanjak of Alexandretta working as domestic servants increased significantly, though what type of labor this entailed and where it was conducted is not reported.55 It is also worth keeping in mind that in a middle-class home, the assistance of one domestic laborer would have still left plenty of tasks in parenting, food preparation, and housekeeping.

Reversing the trend of nineteenth-century de-urbanization in Syria mentioned earlier, after World War I an influx of rural migrants into cities resulted in overcrowding and displacement, leading those with means to decamp from homes and quarters in which their families had lived for generations in favor of homes in newly established quarters of the city. During the Mandate, the population of Damascus doubled and that of Aleppo more than doubled.56 The new homes had conveniences such as hot and cold running water and vented ovens, making elite women’s trips to hammams, wells, and public ovens unnecessary.57 The physical distances may have led to increased psychological distance between elites and others as well, which is evident in the invisibility of poor women in the local women’s press.

Despite the availability of baby formula, which by the 1930s was considered a healthy alternative to breast milk as long as hygienic bottling processes were followed, mothers were pressured to breastfeed.58 In the 1930s, the use of wet nurses was still seen in rural areas, but by the late nineteenth century, it had begun to be considered unhygienic and improper among urban and elite women. A columnist in the monthly Egyptian women’s magazine, Majallat al-sayyidat wa al-rijal asserts, “If the mother is replaced with manufactured milk, the life of the infant is exposed to risk . . . the mother reaps what she sows in the future for her child if she doesn’t feed it her milk. It is impossible to find a well-fed baby from manufactured milk.”59 According to an article in the Aleppo women’s magazine, Sawt al-mar’a al-hur, among the qualities that defines a good mother is that she breastfeeds her child.60

Mothers were expected not only to nurture their children’s bodies, but as part of an emerging focus on building a sovereign nation, women were taught to cultivate their children’s patriotism as well: “Teach him that he has a duty to it [his country]61 to buy national products and eat national products and wear the clothes of his country.”62 This was by no means a call for unskilled labor: “It is incumbent on the nation to take care in its commitment to engage the mother, educating and culturing her,” for which, according to the column’s author, the result will be, “Girls and boys will achieve power in their minds, patriotism and devotion, happiness in the health of their bodies, peace in their minds and maturity in their ideas.”63

Columnists also saw the value in mothers putting their time and energy into raising their daughters, who “might even require greater care . . . and for those for whom it is written that they are to marry, they need to be taught in the essentials of managing a household, as well as tools for health, and how to cohabitate and raise children.”64 The theme of patriotic motherhood recurs frequently in the women’s press in the Middle East from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries.65 Thompson suggests its diffusion in interwar Syria was likely a result of the failure to achieve suffrage; patriotic motherhood was a means of incorporating women into the building of the nation, despite their lack of inclusion in the political community.66

A small group of Syrians found themselves in a better position after the war and were able to benefit from the French presence in Syria. As Philip Khoury’s research shows, there was not much change in the structure of the notable class between the late Ottoman and Mandate periods in Damascus. However, an emerging educated middle class, particularly those schooled in French language, and newly enriched merchants, could better compete with notables for power and cultural currency. Women had an important role in shaping the emerging middle class.67 They created or took advantage of opportunities to enter the public sphere, seeking out education, entertainment, and consumption in a market in which more and more products were becoming available.68

Articles geared towards women in the local press often focused on food. Majallat al-mar’a, which usually published brief items of a half of a page to a full page, printed a two-page editorial on the importance of family meals to reverse the perceived problem of men dining alone; the contributor worried “that the individual among us eats what resembles dinner in a shop (sandwich) or in a cafe or at a hummus vendor or at a hotel or a restaurant has eaten in a hurry at home before a party or in the kitchen at home at the end of one.” This was seen as an issue both among the middle class, in which “many of our families spend a number of days without a meeting between the man and his children,” as well as wealthy families who instead of sitting around a table together, feed themselves as needed from “pots of food set out for this purpose in the kitchen.”69 There was likely an uptick in this type of dining that correlated with families moving away from ancestral quarters. Though they resided in newly built areas, their shops and businesses usually remained in the old quarters, requiring a commute, which in turn gave rise to new iterations of mealtime.70

To stem the trend of solo dining, the Majallat al-mar’a author recommends that the government decree set family meal times, which would lead to “growth in the life of the family.”71 Another column in the same journal reprinted advice from a medical doctor asserting that keeping to an eating schedule was better for one’s digestion.72 Maintaining set meal times was also promoted for the wellbeing of children: a columnist suggests mothers should share specific healthy foods with newly weaned children at ten o’clock in the morning and again at four o’clock in the afternoon.73

DINING OUT: CLASS AND FOOD CHOICES

Smaller scale eating and drinking establishments had been catering to urban populations in Syria throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In most quarters of Damascus, one could buy a cold drink such as lemonade, tamarind juice, or rose water mixed with snow from a sharabti, one of the many beverage peddlers in the city.74 From the beginning of May through summer, enterprising merchants known as thulaj would bring ice stored in caves via donkey down the steep slopes of Qalamun to be purchased by wealthy Damascenes and restaurateurs, allowing them to enjoy a refreshing drink or ice cream before refrigeration became more widespread in urban areas.75 At urban souks, one could purchase a serving of cooked meat from a rotisserie owner or sit down at a small informal dining establishment.76 A man crouching over an outdoor grill preparing meat kebabs for sale can be seen in a 1938 documentary taken in Damascus.77 Australian Army captain Hector Dinning describes grabbing a bite of kebab at butcher’s shop in Aleppo where he was briefly stationed after the war, and being offered sweets, coffee, and other items for his meal that the proprietor would send out for from neighboring stands.78

Though the emerging restaurant culture in urban Syria was much smaller than in Beirut and other cities in the region, a number of dining options arose during the Mandate years. Whereas many restaurants, particularly ones at hotels, were geared towards tourists and business travelers, some of the new restaurants sought to appeal to parents and their children. Mat‘am Asdiyya in Damascus advertised its monthly menus in Majallat al-mar’a. Each day one meal was prepared, such as burghul, spinach with meat, and spinach salad with lemon juice. The following day, diners could order fried fish, cabbage, meat pies and tartar sauce. The ads offered familiar foods along with the ease of not having to prepare an evening meal, inviting diners to “kulu, ishurabu, wa la tusrifu” (eat, drink, and don’t spend); despite its publication in a women’s magazine, the imperative case of the Arabic is used in the masculine plural in the ad, perhaps with the intention of attracting families.79 In Aleppo, a special family rate was advertised for the restaurant at the Claridge Hotel, and Auberge du Bon Coin boasted of its “cuisine familiale.” These advertisements were geared more towards French or French-speaking clientele, as the prices were given in francs in a French publication.80

Patrons who preferred Western cuisine had a few new restaurants to choose from during the Mandate era such as La Rotonde in the Place Merdje in Damascus.81 Visitors to Homs who longed for European fare could dine at the Buffet Hotel de la Gare, advertised in the Commerce du Levant as serving “cuisine française.”82 The Homs hotel must have been relatively new in 1933 as a decade earlier a British official complained during a visit: “There appears to be no chance of obtaining anything but an Arab cuisine.” He also reported that in Hama one could dine on “good plain European food” at a restaurant operated by a French national, but for an exorbitant price.83 Aleppo had many cafes, three or four of which were European style, and a few of which served food, but cafe culture was largely restricted to men. Budding restaurateurs in Palmyra requested money from the Mandate government in 1938 to open European restaurants in order to attract more visitors to the city’s spring festival.84

Europeans and certain Syrians of higher classes may have preferred European restaurants because they considered them more hygienic. The British official who couldn’t find European food in Homs complained the pitcher of water he was served at a cafe there contained a river insect, noting that he has seen waiters at cafes along the Orontes River collecting water in buckets for diners to drink.85 Other Westerners, such as the aforementioned Captain Dinning, in the same vein as Orientalists of the day, seemed to consider consumption of local foods a way to fully immerse themselves in indigenous culture.

Food has long been a way in which to distinguish one’s self from the Other. In Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Pierre Bourdieu writes: “The most intolerable thing for those who regard themselves as the possessors of legitimate culture is the sacrilegious reuniting of tastes which taste dictates shall be separated.”86 This is particularly true for “groups closest in social space, with whom competition is most direct and most immediate.”87 Class is not only defined by financial means, but by cultural capital and access to power.

Europeans and French-speaking Syrians, who were often Christians educated in French missionary schools, had better access to European cultural capital and many therefore considered themselves of a higher class. This new urban middle professional class began to emerge in the late Ottoman period, as the arrival of Western missionaries and capitalists in the Levant following the Tanzimat reforms brought educational and financial opportunities for some Syrians.88 As Toufoul Abou-Hodeib writes of late-Ottoman Beirut, the rise of the middle class and an increase in imports from abroad fed a boom in consumerism. A shift in the use of domestic space, and an emerging fondness for material possessions, became another marker of class.89 Though Abou-Hodeib does not address food preferences in her study, it is an interesting site of research for the late Ottoman period and Mandate era because increased international trade brought more diverse food products to local markets. However, class background and whether one spoke French does not seem to have been a factor in gustatory consumption choices in the way that home design and clothing styles were. Some imported foods such as canned sardines, European cheeses, and biscuits were imported in quantities too high to have been purchased exclusively by the relatively small number of foreigners living in Syria. Such items would not have been prohibitively expensive for middle-class consumers. It is difficult to gauge exactly who was buying such products, or whether anyone would have considered the consumption of sardines a signifier of sophisticated taste, but it does show that expanding markets and an increase in expendable income resulted in new experiences in eating for some Syrians.

A clash of classes was evident in Damascus in its small but growing restaurant culture. The society editor of Les Echos declared that the Hotel Victoria, the site of many banquets and society parties, “is not for all classes, it is but for one people, chic people, and that is all.”90 According to the item’s author, the fundraising gala for the charity Goutte de Lait, hosted and attended by mostly women, was too crowded with 600 to 700 guests and overly diverse. The article includes the names of a number of European women in attendance, along with names of women from “the usual graceful contingent from Bab Tuma,” a predominantly Christian quarter of Damascus. Another article in the same newspaper a few weeks later praises the crowd at a party celebrating mi-carême, mid-Lent, at the Hotel Victoria, noting if it had been held at Hotel Abbasié instead, readers would have risked “rubbing shoulders with a type of people not of your station but who [had] paid the ten-franc entry fee.”91

An advertisement announcing the opening of the Orient Palace Hotel appeared in the Damascus daily al-Qabas. Orient Palace chefs would prepare “delicious food . . . whatever is ordered appropriate for each taste.” In contrast to the tone of Les Echos, the Orient Palace was to be a place for anyone who could afford it. It would showcase “Western taste complimented with beautiful Arab art.” Taste in this case was a matter of preference, not class. While many Syrians of means focused their newfound power as consumers on “Western” and “modern” products, at the same time Syrian producers learned how to adopt European concepts and products for local tastes, visible in the establishment of a sweets industry in Damascus and Aleppo during the interwar period, the products of which were more affordable locally than European sweets.92

HYGIENE, CLASS, AND URBAN CONSUMERISM

Among the stated goals of France’s mission civilisatrice in its outre-mer territories was the amelioration of public health and hygiene. As Daniel Neep has shown, hygiene, which in the eyes of the French High Commission was equated with scientific rationale and modernity, was used to justify the often violent control and monitoring of public space. Though hygiene had also been integral to urban planning in the late Ottoman period, it had not been an area of political control as it was under the French.93 The French mission was made easier by the availability of new technology, such as aerial surveillance and telephone networks.

Hygiene was also a tenet of the discourse on domesticity, which spread internationally during the interwar period via both state and nonstate actors. Along with taste, hygiene was another field used by the urban elite to distinguish themselves from the poor. Not only was the diffusion of hygienic practices a part of the colonial project, but elite Syrians maintained an interest in the expansion of hygiene among the poor, as food systems touched everyone. The journal Al-zira‘a al-haditha (Modern agriculture) published in Hama advises landowners or supervisors how to instruct their workers on the best way to milk animals, the proper location for milking, how to clean milk containers, and how mothers should handle food for children.94 Domestic science was used as a tool of colonialism to reach where the Mandate could not—inside the home. This movement in Syria coincided with a rise in consumerism.

To be competitive in the market, food sellers had to demonstrate that their products were more hygienic than others. During the 1920s and 1930s as ice manufacturing and refrigeration became more widely available in cities, creameries began increasing their table butter production, which became more and more popular with urban consumers.95 This butter was made with cow’s milk. Though sheep and goats were more prevalent in Syria, cattle were kept in larger towns and cities for milk.

Western observers bemoaned the lack of modern dairy facilities in Syria, but most Syrians consumed locally produced milk and dairy products.96 Syrian-made butter was valued by local shoppers, making it difficult for French butter producers to sell their more expensive product, which concerned them as the price of butter on the international market began falling in 1928.97 Though it would never supplant samn as a preferred cooking fat, the market for locally made butter grew more competitive during the Mandate years, as is evident in the increase in product choices and advertisements. In order to sell a trademarked product in Syria and Lebanon, both Syrian and foreign companies had to have the product and its logo officially registered with a marque de fabrique. In 1926, Michel Assad Jabbour of Damascus registered his Ferme Jabbour’s cream butter with a drawing of children dancing around a cow. In 1929, Jabbour replaced the drawing with a picture of a cow in profile and included the words “beurre frais de table,” guaranteeing that the product was made with fresh cream.98 The same issue of the Bulletin Officiel lists another marque de fabrique for butter from a different dairy, Ferme Chouranelly, using the drawing from the 1926 Ferme Jabbour packaging. Cherif Chewkat registered his Aleppo farm’s butter in 1930, with the packaging in both French and Arabic.99

Local branding and packaging for food products was a relatively new phenomenon in Syria, reflecting its recent European innovation in the middle of the nineteenth century. Syrian businesses still relied on word-of-mouth and personal relationships for marketing, but facing more competition, the growth of the local press in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries offered new opportunities for to expand a seller’s reach. Manufacturers could use brand names and advertising to market trust and cleanliness to consumers, in response to increased fears of adulteration and spoilage as food chains grew longer through improvements in transportation and marketing networks.100

A 1928 newspaper advertisement for Ferme Chouranelly in Les Echos claims that the huge demand for its butter led to numerous forgeries and imitations. Customers are advised to look at the inside of the packaging for the farm’s signature.101 Another Damascus dairy farm, Ferme Azem or Mazra‘a ‘Azam, used hygiene and science as a selling point in a 1929 ad in Les Echos, touting the owner’s training as a veterinarian.102 The art for the ad consists of a drawing of a cow next to a woman carrying a bucket in each hand in a Western-style modest dress, the black skirt hitting just below the knee, with short sleeves and a white apron, along with a white hair bonnet and black pumps. A few months later, the company launched a new ad adding the contention: “All butters look alike, only fresh butter from Ismet Azem has all the qualities of purity and cleanliness.”103 Both versions of the ad provided Arabic writing in addition to the French. Though the Ferme Azem may not have met the hygiene standards of Mandate officials, the language used in the packaging seems to have been influenced by the discourse around hygiene and domesticity, geared towards women.

CONCLUSION

The changes in the lives of Syrian urban middle- and upper-class women after World War I were tangible. Electricity spread to more urban neighborhoods, the number of automobiles on newly built roads increased, and consumer choices widened. Education and news publications were becoming more accessible to middle-class women. Leisure-time activities broadened as well, with options for restaurants, tourism, and cinema expanding. The changes experienced by rural poor women were not as clearly defined and certainly less exciting than what was witnessed by their elite urban counterparts. Economic and demographic pressures created by the war, climate, and French Mandate policies often forced the rural poor to work harder for less money. The stories of rural women were not told in newspapers and journals, which they certainly were not reading. Their absence in the imagined community of print rendered them invisible to urban elite women. The lives of disparate groups of women, however, were linked through food chains. One way of bringing the lives poor women in Syria during the early to mid-twentieth century to light is to examine networks of food production, and work backward by looking at food consumption to uncover the labor expended to produce it.

NOTES

James Gelvin, “Was There a Mandate Period? Some Concluding Thoughts,” in Routledge Handbook of the History of the Middle East Mandates, eds. Andrew Arsan and Cyrus Schayegh (New York: Routledge, 2015), 420.↩︎

Elizabeth Thompson, Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal Privilege, and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000).↩︎

Sources for this article include French ethnographers such as Albert de Boucheman and Jacques Weulersse, who were working on behalf of the Mandate. Though indigenous accounts would be preferable, written records for rural Syria during the Mandate are scarce, and academic monographs on the era frequently cite such works, though not uncritically. See, for example, Philip Khoury, Syria and the French Mandate: The Politics of Arab Nationalism, 1920–1945 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987); Daniel Neep, Occupying Syria under the French Mandate: Insurgency, Space and State Formation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012); Thompson, Colonial Citizens.↩︎

Charles Issawi, The Economic History of the Middle East, 1800–1914 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966), 238; Norman Burns, The Tariff of Syria, 1919 to 1932 (Beirut: American Press, 1933), 63–65.↩︎

James Reilly, “Women in the Economic Life of Late-Ottoman Damascus,” Arabica, t. 42, fasc. 1 (March 1995): 100.↩︎

George Hakim, “Conditions of Work in Syria and the Lebanon under French Mandate,” International Labour Review (1939): 513, 517.↩︎

James Gelvin, “‘Modernity,’ ‘Tradition,’ and the Battleground of Gender in Early 20th-Century Damascus,” Die Welt des Islams 52 (2012): 9.↩︎

MAE/Office du Levant/20, Le Haut Commissaire à Monsieur Pierre Berthelot, Directeur de l’Office Economique et Commercial, “Renseignements sur le régime du travail,” 10 May 1927.↩︎

M. Berenstein, “The Levant States under French Mandate and Problems of Emigration and Immigration in Syria and the Lebanon,” International Labour Review 33 (May 1936): 710.↩︎

George Hakim, “Industry,” in Economic Organization of Syria, ed. Sa‘id Himadeh (Beirut: American Press, 1936), 148.↩︎

“Working Conditions in Handicrafts and Modern Industry in Syria,” International Labour Review 39, no. 3 (March 1934): 410.↩︎

Hakim, “Conditions of Work,” 520.↩︎

Thompson, Colonial Citizens, 35.↩︎

In December 1926, the exchange rate was 127.5 piasters to the U.S. dollar, making 25 piasters a day equivalent to about $0.32. In June 1928, the franc was stabilized at 65.5 milligrams of gold, which made 20 francs approximately equivalent to one Syrian pound or $0.79. Sa‘id B. Himadeh, “Monetary and Banking System,” in Economic Organization of Syria, 266. There was a great deal of currency fluctuation during the Mandate: five years later in July 1933, 1 dollar was equal to 92 Syrian piasters, or 18.40 French francs. NARA, RG 166, box 472 (Agriculture General), Foreign Agricultural Service Narrative Reports; Syrian Agricultural Policy, “Commercial Traveler’s Guide to North Africa and the Near East,” 22 May 1933.↩︎

MAE/Office du Levant/20, Le Haut Commissaire à Monsieur Pierre Berthelot, Directeur de l’Office Economique et Commercial, “Renseignements sur le régime du travail,” 10 May 1927. For the sake of comparison, in 1928 in the United States, a male laborer producing cotton goods, among the lowest paying industries recorded in the survey, earned on average $14.76 a week for approximately 40 hours, and a female laborer earned about $12.00 a week. US Department of Labor, Handbook of Labor Statistics 616 (1936), 875, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112032654953;view=1up;seq=893.↩︎

Bread and flour prices fluctuated considerably during the Mandate depending on the price of wheat and other economic conditions. “Echos de la ville,” Les Echos, 8 August 1929, 3. In the United States the average cost of a pound of bread in 1928 was $0.09. Using the above wage averages as our base, a male cotton worker earning $0.39 an hour would have had to spend a much lower percentage of his salary on bread than a Syrian agricultural laborer. US Department of Commerce Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, pt. 1 (1971), 213, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951000014585x;view=1up;seq=233.↩︎

Margaret Meriwether, “Women and Economic Change in Nineteenth-Century Syria: The Case of Aleppo,” Arab Women: Old Boundaries, New Frontiers, ed. Judith Tucker (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 79.↩︎

Abdallah Hanna, “The Attitude of the French Mandatory Authorities towards Land Ownership in Syria,” in The British and French Mandates in Comparative Perspective, eds. Nadine Méouchy and Peter Sluglett (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 461–63; Elizabeth Williams, “Cultivating Empires: Environment, Expertise, and Scientific Agriculture in Late Ottoman and French Mandate Syria,” (PhD diss., Georgetown University, 2015).↩︎

NARA, RG 166, box 473, Foreign Agricultural Service Narrative Reports, “Crop Harvests in the Damascus Consular Districts: Walnuts,” 9 December 1927.↩︎

NARA, RG 166, box 473, Foreign Agricultural Service Narrative Reports, “The Agricultural Outlook for 1925: Pistachio Nuts,” 5 August 1925.↩︎

“Activité des industries à Alep durant l’année 1927 et le nombre des travailleurs utilisés durant cette même période,” Bullétin economique annuel de la Chambre de Commerce d’Alep 16 (31 December 1927): 67.↩︎

“L’activité industrielle de Damas: Les sucreries,” Commerce du Levant, 22 October 1935, 2.↩︎

See, for example, Elizabeth Fernea and Richard Lobban, Middle Eastern Women and the Invisible Economy (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1998).↩︎

Abdullah Hanna, Al-falahun yarun tarikhahim fi Suriyya al-qurn al-‘ashreen: Dirasa tajma‘a bayn al-tarikh al-marwi wa al-tarikh al-maktub (Aleppo: Al-Mansha al-Kadima, 2009), 39–40.↩︎

Albert de Boucheman, Une petite cite caravanière: Suhné (Damascus: IFEAD, 1937), 91.↩︎

Thompson, Colonial Citizens, 157.↩︎

MAE/Office du Levant/20, Le Haut Commissaire à Monsieur Pierre Berthelot, Directeur de l’Office Economique et Commercial, “Renseignements sur le régime du travail,” 10 May 1927.↩︎

MAE, Rapport a la société des nations sur la situation de la Syrie et du Liban, 1929 (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1930), 68.↩︎

Stuart Dodd, A Controlled Experiment in Rural Hygiene in Syria (Beirut: American Press, 1934), 93.↩︎

“Tarbiyya al-haywanat al-alifa al-halwiyya,” Al-nashra al-iqtiṣadiyya li-l-ghurfa al-tijariyya bi Dimashq (1937): 43.↩︎

Louise Sweet, Tell Toqaan: A Syrian Village (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1960), 102. Though Sweet conducted fieldwork for this book in 1954, eight years after Syrian independence, it is a useful resource because of her access to rural Syrian women during a time when there was little written by or about them.↩︎

“L’importation des machines et appareils frigorifiques en Syrie et au Liban,” Commerce du Levant, 30 June 1936, 2.↩︎

Carol Palmer, “Milk and Cereals: Identifying Food and Food Identity among Fallahin and Bedouin in Jordan,” Levant 34 (2002): 182.↩︎

Palmer, “Milk and Cereals,” 184.↩︎

Charles Pavie, État d’Alep: Renseignements Agricoles (Aleppo: Services économiques, 1924), 90, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k8520202.↩︎

Sweet, Tell Toqaan, 104.↩︎

John Lewis Burckhardt, Travels in Syria and the Holy Land (London: John Murray, 1822), 293; Françoise Aubaile-Sallenave, “Al-Kishk: The Past and Present of a Complex Culinary Practice,” in A Taste of Thyme: Culinary Cultures of the Middle East, eds. Richard Tapper and Sami Zubaida (New York: I.B.Tauris, 1994), 122.↩︎

Aubaile-Sallenave, “Al-Kishk,” 103–39.↩︎

Muhammad Sa‘id al-Qasimi, Jamal al-Din al-Qasimi, and Khalil al-‘Azm, Qamus al-sina‘at al-shamiyya (Paris: Mouton, 1960), 388.↩︎

Palmer, “Milk and Cereals,” 192.↩︎

Louis Jalabert, “Un peuple qui veut vivre. Les Arméniens émigrés en Syrie et au Liban,” Études, no. 217 (1933): 59.↩︎

P. C. Williams, F. J. el-Haramein, and B. Adleh, “Burghul and Its Preparation,” Rachis: Barley, Wheat and Triticale Newsletter 3, no. 2 (June 1984): 29.↩︎

Afif Tannous, “Food Production and Consumption in the Middle East,” Foreign Agriculture, no. 7 (1943): 253.↩︎

Henri Charles, “Quelques travaux des femmes chez les nomads moutonniers de la région de Homs-Hama,” Bulletin d’Études Orientales 7–8 (1937–1938): 212.↩︎

Sweet, Tell Toqaan, 133.↩︎

Paul Devlin, “The Screen Traveler,” filmed 1938, 2:33–3:25, accessed 20 February 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ungXKUmlXzg.↩︎

Dodd, A Controlled Experiment, T62.↩︎

Richard Thoumin, Géographie humaine de la Syrie Centrale (Paris: Librairie Ernest Leroux, 1936), 211.↩︎

Dodd, A Controlled Experiment, T62.↩︎

Al-Ustadha Ri’afa al-Nashar, “Hal wafit al-umuma haqiha ya sayyidati?” Majallat al-mar’a 3 (June 1947): 16.↩︎

Nudra Jirah, “Al-tarbiyya al-‘amaliyya,” Sawt al-mar’a al-hur (25 December 1946): 35.↩︎

Omnia Shakry, “Schooled Mothers and Structured Play: Child Rearing in Turn-of-the-Century Egypt,” in Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East, ed. Lila Abu-Lughod (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), 141.↩︎

Sara Pursley, “A Race against Time: Governing Femininity and Reproducing the Future in Revolutionary Iraq, 1945–63” (PhD diss., City University of New York, 2012), 14.↩︎

Abdallah Hanna, Dayr ‘Atiyya: Al-tarikh wa al-‘amran (Damascus: IFEAD, 2002), 236.↩︎

MAE/Office du Levant/20, Le Haut Commissaire à Monsieur Pierre Berthelot, Directeur de lʼOffice Economique et Commercial, “Renseignements sur le régime du travail,” 10 May 1927.↩︎

Philip Khoury, “Syrian Urban Politics in Transition: The Quarters of Damascus during the French Mandate,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 16, no. 4 (November 1984): 516.↩︎

Jean-Claude David and Dominique Hubert, “Maisons et immeubles du début de XXème siècle à Alep,” Les cahiers de la récherche architecturale, vol. 10/11 (1982): 102.↩︎

Josep Barona, “International Organizations and the Physiology of Nutrition during the 1930s,” Food and History 6, no. 1 (January 2008): 159.↩︎

“Al-umm wa al-tifl: Mundhu al-hamal ila al-fitam, al-hamal wa al-wilada yashan mizaj al-mar’a,” Majallat al-sayyidat wa al-rijal (June 1929): 527; as it became more difficult to publish in Syria and Lebanon during the Great Depression due to the cost of paper and advertising, sleek women’s magazines from Egypt offered an attractive alternative for Syrian women with the means to pay the subscription costs. Thompson cites the circulation of Majallat al-sayyidat wa al-rijal in Syria. Thompson, Colonial Citizens, 215.↩︎

Nudra Jirah, “Al-tarbiyya al-‘amaliyya,” Sawt al-mar’a al-hur (25 December 1946): 35.↩︎

The author uses al-watan in this context, but in the same paragraph she uses al-bilad, seemingly interchangeably.↩︎

Al-anisa “zanbaqa al-wadi” (Miss lily of the valley), “Al-sayyidat fi al-mujtamaʻa: Al-mar’a wa al-nahḍa al-qawmiyya,” al-Dad, vol. 3 (1938): 136.↩︎

Fika al-‘Asla, “Al-sa‘ada al-manzaliyya,” Majallat al-mar’a, 5 (August 1947): 31.↩︎

Anisa Hilal, “Wajibat al-umuma,” al-Dad, vols. 5–6 (May, June 1944): 149.↩︎

Thompson, Colonial Citizens, 143; Omnia El Shakry, The Great Social Laboratory: Subjects of Knowledge in Colonial and Postcolonial Egypt (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007), 179; Lila Abu-Lughod, “Introduction: Feminist Longings and Postcolonial Conditions,” in Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East, ed. L. Abu-Lughod (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998), 8.↩︎

Thompson, Colonial Citizens, 143. Professor El Shakry’s name is spelled differently depending on the publication.↩︎

Philip Khoury, “Syrian Urban Politics in Transition: The Quarters of Damascus during the French Mandate,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 16, no. 4 (November 1984): 507–40.↩︎

Thompson, Colonial Citizens, 36.↩︎

Al-Ustadh Ali Haidar al-Rikabi, “Waqt al-ta‘am,” Majallat al-mar’a, no. 1 (April 1947): 24.↩︎

Khoury, “Syrian Urban Politics,” 535; Thoumin, “Deux Quartiers,” 111.↩︎

Al-Rikabi, “Waqt al-ta’am,” 24.↩︎

“Quwwa’ ad li-l-ṣaha,” Majallat al-mar’a, no. 7 (November 1947): 28.↩︎

“Sahat fi al-quriyyah” [Health in the village], Al-zira‘a al-haditha (8 October 1929): 37.↩︎

Al-Qasimi, 203.↩︎

Thoumin, Géographie Humaine, 168.↩︎

Paul Baurain, Alep, autrefois, aujourd’hui: Alep à travers l‘histoire, population et cultes, la ville, les resources, la vie publique, la vie privée (Alep: Castoun, 1930), 256.↩︎

Paul Devlin, “The Screen Traveler,” filmed 1938, 1:10–1:20, accessed 2 February 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ungXKUmlXzg.↩︎

Hector Dinning, Nile to Aleppo With the Light-Horse in the Middle East (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1920), 63. http://www.scotlandswar.co.uk/pdf_McBey_Nile_to_Aleppo.pdf.↩︎

Majallat al-Mar’a, no. 2 (May 1947).↩︎

Baurain, Alep, 332.↩︎

See for example: “La rotunde, restaurant français 1ère ordre,” Les echos de damas (29 October 1931).↩︎

Sté. des Grands Hôtels du Levant, Commerce du Levant, Beirut (1 November 1933).↩︎

FO 371/9054, Palmer to Secretary of State for the Foreign Office, “Tour in Northern Portions of Damascus State,” 6 July 1923, in Jane Priestland, Records of Syria, 1918–1973 3 (Oxford: Archive Editions, 2005), 72.↩︎

CADN/CP, vol. 979, “Fête du printemps du Palmyre,” 26 March 1938.↩︎

FO 371/9054, in Priestland, Records of Syria, 72.↩︎

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984), 55.↩︎

Bourdieu, Distinction, 60.↩︎

Keith David Watenpaugh, Being Modern in the Middle East: Revolution, Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Arab Middle Class (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 19.↩︎

Toufoul Abou-Hodeib, A Taste for Home: The Modern Middle Class in Ottoman Beirut (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017).↩︎

“Echos mondain: A l’annexe Victoria,” Les echos (3 February 1929): 2.↩︎

“Echos mondain: La mi-carême à Damas,” Les echos (10 March 1929): 2↩︎

Toufoul Abou-Hodeib describes how Levantine furniture makers based their products on European models adding local materials and artisan craft to build a large market for furniture in the late nineteenth century. Abou-Hodeib, A Taste for Home, 161.↩︎

Neep, Occupying Syria under the French Mandate.↩︎

“Shir̜’ at al-halab al-sahtiyyah” [Undertaking healthy milk], Al-zira‘a al-haditha 8 (May 1925): 203, 225; “Sahat fi al-quriyyah” [Health in the village], Al-zira‘a al-haditha (8 October 1929): 37.↩︎

Albert Khuri, “Agriculture,” in Economic Organization of Syria, ed. Sa‘id Himadeh (Beirut: American Press, 1936), 106.↩︎

Pavie, Etat d‘Alep, 89.↩︎

Haut Commisariat de la République française auprès des Etats de Syrie, du Grand Liban, Etat des Alaouites, Etat du Djébel-Druze, Bulletin économique mensuel des pays sous mandat français (1922), 13; League of Nations Economic Committee, The Agricultural Crisis, vol. 1, (Geneva: Series of League of Nation Publications, 15 June 1931), 39.↩︎

Haut Commissariat de la République française en Syrie et au Liban, “Marques de fabrique déposées à l’office de protection de la propriété commerciale & industrielle,” in Annexe au Bulletin Officiel du Haut-Commissariat de la République Française en Syrie et au Liban, no. 22, 23 (30 November 1929), 7.↩︎

Ibid., no. 16, (31 August 1930), 2.↩︎

Peter Atkins, Liquid Materialities: A History of Milk, Science, and the Law (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010), 59.↩︎

Ferme Chouranelly, Les Echos 2 (18 November 1928): 4.↩︎

Ismet Azem, “Beurre Frais de Damas,” Les Echos 38 (18 April 1929): 3.↩︎

Ismet Azem, “Beurre Frais de Damas,” Les Echos 72 (25 July 1929): 4.↩︎