Cherine Fahd

CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN ARTISTS FROM THE MIDDLE EASTERN DIASPORA

Abstract

For nearly two decades contemporary artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora have enjoyed international acclaim with significant representation across major international exhibitions in Western art centers. This success can be attributed in part to the strong sociopolitical concerns that characterize their practices. Like their international counterparts, Australian artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora contribute to the enduring relationship between art and politics and yet despite this, the practice of contemporary Australian artists from the diaspora is scarcely known internationally. This article seeks to offer some redress by introducing seven contemporary Australian artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora who for the past decade have achieved institutional recognition in Australia.

INTRODUCTION

For nearly two decades, artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora have achieved significant international recognition with substantial presence across major international exhibitions, biennales, and museums. Walid Raad, Shireen Neshat, Mona Hatoum, Emily Jacir, Ghada Amer, and Akram Zaatari represent a growing number of acclaimed international practitioners from the Middle East region. An important and early example of this representation was Documenta 11, held in 2002 and curated by Okwui Enwezor.1 This important exhibition featured Hatoum, Neshat, Raad’s the Atlas Group, Fareed Armaly, and Kutluğ Ataman, among other well-known artists. 2 Artists exhibiting in Documenta have since sustained critical career successes, as is the case with Raad who recently delivered a major survey exhibition at MoMA (the Museum of Modern Art) in New York.

Despite these international examples, the practices of contemporary Australian artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora are scarcely known outside of Australia.3 This article seeks to address this gap by introducing seven such artists:4 Hany Armanious, Khaled Sabsabi, Joanne Saad, Hossein Ghaemi, Cigdem Aydemir, Raafat Ishak, and Fassih Keiso, describing key features of their works past and present, and the themes that define their practices.5 Throughout the past decade these artists have established institutional recognition in Australia.6

In recent years, the institutional appetite for artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora has been significant. Their work is often characterized by strong political stances and is frequently aligned with curatorial briefs addressing global political conflicts, divisions between Eastern and Western ideologies, and postcolonial agendas. Two recent examples illustrate this: Raad’s exhibition at MoMA, in New York, and Jacir’s exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery, in London. Raad’s exhibition release highlights his work’s political preoccupations:

Dedicated to exploring the veracity of photographic and video documents in the public realm, the role of memory and narrative within discourses of conflict, and the construction of histories of art in the Arab world, Raad’s work is informed by his upbringing in Lebanon during the civil war (1975–91), and by the socioeconomic and military policies that have shaped the Middle East in the past few decades.7

Jacir’s exhibition release notes equally rich sociopolitical themes: “Known for her poignant works of art that are as poetic as they are political and biographical, Jacir explores histories of migration, resistance and exchange.”8

There is a comparable political dimension characterizing the works of Australian artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora. These artists, like their international counterparts, play an important role in ensuring that the longstanding relationship between art and politics continues. Australian artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora are largely making and exhibiting work that is concerned with sociopolitical issues impacting Australia and its peoples, issues that straddle cross-cultural identity, race and religion, conflict and war, gender stereotyping, nationhood, and displacement, as well as drawing on the aesthetic and mystical traditions of their homelands.

HANY ARMANIOUS

Hany Armanious was born in 1962 in Ismalia, Egypt, and migrated to Australia with his family at the age of six. He is one of Australia’s leading contemporary artists. I first encountered his work in 1998 when Untitled Snake Oil (1998) won him the prestigious Moet & Chandon Art Prize. In this work, an assortment of nineteen champagne, wine, port, and sherry glasses were displayed upturned on a table. Using a vinyl material called hot melt, he cast the space inside of the glasses to create colored forms which he placed on top of each of the corresponding vessels that sat on the table. The effect of fashioning a magical altar from household items was mesmerizing (figure 1).

At the time, this work invoked an effortless approach to sculpture through playful transformation of everyday objects and an experimental approach to casting that shied away from using traditional materials. His extensive history of exhibitions has seen him cast an eclectic range of everyday objects in unconventional materials such as spray foam, hot melt, polyurethane resin, polystyrene, epoxy, silicone, polypropylene, copper, and nickel plate, as well as traditional materials such as wax, wood, and more recently, bronze and marble.9 For this reason his work stands out, offering Australian art a refreshingly unorthodox approach to sculpture.

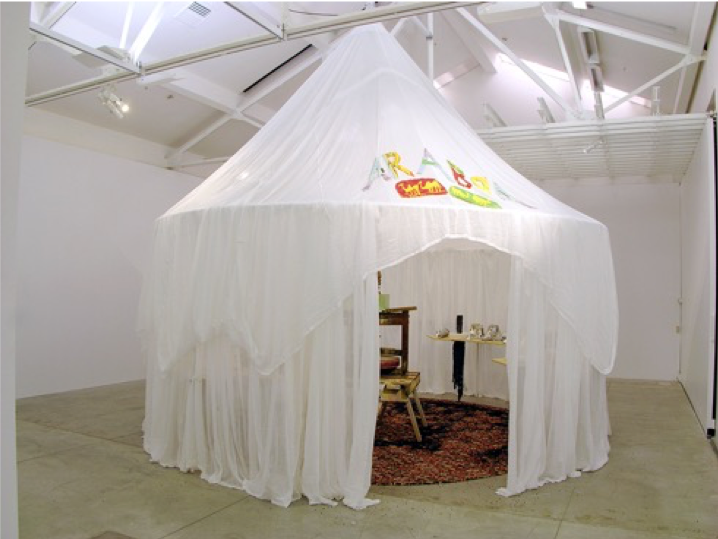

Interestingly, Armanious is the one artist of the seven mentioned here whose practice bypasses sociopolitical themes arising from his ethnicity and migration from Egypt to Australia. In introducing Armanious’s practice first I was interested in knowing if he has consciously sidestepped the principles from which many Australian artists of Middle Eastern ancestry make work from; principles framed by identity politics, racial politics, religious and gender politics, conflict in their homeland, and more generally the politics of the Other. In 2004 and 2005 his work made references to “Arabia” (figure 2) but this was only cursory, less politically driven, and more formal in interest. His concerns at the time appeared to lie in the formalist quality of objects: the patterns, shapes, materiality, and colors synonymous with the Arab world, for example, the turns of wood on an nargileh, the patterns of a Persian carpet, or the shape of an Oriental tent one might see in a desert scene from a Hollywood film.10 When I asked the artist whether he had deliberately avoided the political terrain associated with being an Arab Australian artist, he responded:

This type of work hijacks art as a means to institutionalise polemics. I’m interested in other people’s stories and experiences, but I don’t think that art is the right platform for these narratives. I don’t resist my heritage but at the same time I know it’s not so special. National sentiments of any kind I find abhorrent. Being both Egyptian and Australian, and at the same time neither, is quite liberating. For me, art’s true privilege and power is in its non-location.11

Armanious is passionate and political in his views about art and yet his work is conceptually singular; rejecting the politics of representation activated by the six other artists discussed here and the international examples cited earlier.

Significantly, Armanious’s critical and commercial recognition reached a peak in 2011 when he represented Australia at the fifty-fourth Venice Biennale with a solo exhibition, The Golden Thread (2011), commissioned for the Australian Pavilion. Armanious is the first and only artist from the Middle Eastern diaspora to represent Australia since it began participating in 1954.

For Venice, he drew on his long history of casting to reproduce and transform insignificant everyday objects into a peculiar assemblage. For example, Adzeena Persius (2010) provoked the viewer to form perplexing associations between materials, subjects, and objects (figure 3). In this monumental work the artist stacked five bronze-cast Ikea tables on top of one another, erecting a perilous tower that forced the viewer to look up to a metaphorical heaven. Armanious’s Ikea tables were transmuted from throwaway furniture into exquisite bronze. On the bottom table Armanious placed a replica of a paper crown sourced from the fast-food chain Burger King, reproduced in gold-plated silver and adorned with semi-precious stones (figure 4). The crown was instantly familiar as an object I had received as a child, and yet in gold-plated silver and with colorful tourmaline, rubelite, blue topaz, garnet, and citrine gems it was transformed into a fairy-tale object.12

In an online interview describing his process the artist articulates his sculptural objective as one of “redescribing the object” with “poor materials.”13 He states a desire to recreate an “approximation” rather than a replica of ordinary things.14 These ordinary things are overlooked objects that he might find lying about his studio like shoes, pin boards, and hardware tools.

In another work from the biennale, Le Nez (2010), Armanious recalls Alberto Giacometti’s 1947 work of the same title, except in his contemporary homage he has replaced Giacometti’s infamous bronze nose with a reproduction of an iconic Australian garden tool―the leaf blower. Cast in pigmented polyurethane resin, it hangs uselessly suspended from a bronze frame (figure 5), like a huge erect penis (or “fallic intrusion” as the artist has described it).15 Both these works recall monumental sculpture and yet their main subjects―a paper crown, Ikea tables, and a garden leaf blower―remain determinedly un-heroic.

KHALED SABSABI

Khaled Sabsabi was born in 1965 in Tripoli, Lebanon. Owing to the outbreak of civil war, his family migrated to Sydney in 1978. He lives and works in Sydney’s Western Suburbs, a culturally diverse area known for settling large communities of migrants and refugees from the Middle East, Africa, China, and Vietnam. He is an incredibly prolific artist and has recently achieved some international success with inclusion in major biennales such as the third Kochi-Muziris Biennale, the first Yinchuan Biennale, fifth Marrakech Biennale, eighteenth and twenty-first Biennales of Sydney, ninth Shanghai Biennale, and Sharjah Biennial 11. He has won significant prizes in Australia such as the Helen Lempriere Travelling Art Scholarship in 2010, the sixtieth Blake Prize in 2011, the MCG Basil Sellers Fellowship in 2014, the Fishers Ghost Art Award in 2014, and the NSW Western Sydney Arts Fellowship in 2015.

In contrast to Armanious’s practice, Sabsabi’s work is at times controversial and persuasive. His work is driven by acute political engagement with the migrant experience of those, who like him, were displaced to Australia by conflicts in the Middle East. Sabsabi re-presents his personal experience in intensely critical, political terms. He doesn’t shy away from experiences of conflict, the misunderstandings between Eastern and Western ideologies that govern nationhood, and the subsequent issues concerning identity, religion, and one’s sense of “home.”

Sabsabi works across diverse mediums such as video, sound, sculpture, painting, and photography. Unique to his early creative experience was his career as a hip-hop performer. This performance history characterizes much of his current work that utilizes video technology and hypnotic sound to create immersive video experiences made up of large and/or multiple screens often repeating the same images over and over to a mesmerizing soundtrack.

My first encounter with Sabsabi’s work was in 2000 in an exhibition titled East of Somewhere.16 The artist exhibited a series of screen-printed T-shirts that prominently and repeatedly featured the face of then-Taliban leader, Osama bin Laden. The work was titled Where We At (2000) and featured twenty T-shirts hanging on a self-styled washing line equipped with wooden pegs and lawn carpet (figure 6). The work combined elements of Australian cultural life: a washing line hung over a perfect patch of green grass with ubiquitous white washing, a scene metaphorically describing “the great Australian Dream” of home ownership, except in Sabsabi’s provocative version the washing reveals the face of Western Enemy Number One―Bin Laden. At the time, I recall heavy criticism of this work. The work was admonished for its perceived valorization of terror. In fact, the work’s objectives were far more complex in its attempts to juxtapose two incongruous symbols―the Australian backyard and terrorism.

Seventeen years later Sabsabi continues to brutally and ironically picture divergences in Australian culture from the perspective of marginalized and displaced communities. He draws out Western preconceptions about Islam, religion, war, and culture, forcing the viewer to contend with reality rather than the stereotypes presented in the news. A work that achieves this acutely is Naqshbandi Greenacre Engagement (2011). This quietly provocative work (figures 7, 8) won him one of Australia’s most prestigious art prizes, the 2011 Blake Prize for Religious Art. In this, the artist subtly conjoins the folkloric Australian Boy Scout hall and the scout flag with a religious performance by a Sydney Sufi community. Three television monitors sit on the floor adjacent to a Persian rug on which viewers are able to sit cross-legged and watch the screens before them. Pictured before the viewer is a devotional scene featuring Sufi Muslims seated on the floor in a community scout hall. They are chanting loudly and the repeated sound makes them appear transcendent and out of place in the ordinary room they inhabit. As the group of men and women chant in unison, children walk in and out of the scene, some climbing on their mothers, another baby asleep on its mother’s shoulder, and others walking casually in and around the hall.

What’s interesting about this scene is that it is reminiscent of the many videos and still images the media portray of ISIS; groups of men seated in a semi-circular fashion facing a camera, and a room adorned by flags. In Sabsabi’s scene there are also flags, and on quickly surveying the work one might mistake them for political flags (figure 8). Rather uncannily though, they are Boy Scout flags and one of them looks identical to Hezbollah’s flag: both yellow and green. One might mistake the worshippers for Hezbollah sympathizers. As the artist noted in an interview with ABC journalist William Verity,

If you looked at that image and you didn’t bother looking closer into the image, you would think they were three Islamic flags. It’s not until you really look at the hall that you see it’s a Scout’s hall, but if you went off first judgment, it’s a terrorist-looking gathering, and you’ve missed out on the picture. And that’s part of the work.17

Transcendence is a theme evident in another work that draws parallels between sporting fans and religious devotion. In Wonderland (2014), the artist recorded the hypnotic chanting of soccer fans for the Western Sydney Wanderers, the football club of Sabsabi’s Sydney home. In this work, two screens present a large stadium of men chanting the team’s anthem among other fan cries (figure 9). Two men stand in front of each of the crowds leading them into a transcendental state; the men appear bare-chested and heroic, recalling ancient warrior figures. The piece is primal, evoking an ancient charge to war and drawing parallels with Hollywood cinematic tropes. For example, one can easily draw links between the suburban football fans’ fervor and the bloodthirsty crowds depicted in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000).

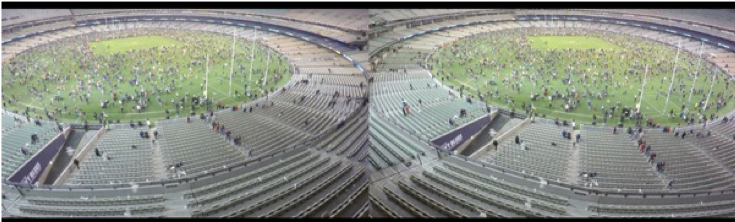

This is not the only parallel to the Gladiator film. In For the Fans Part D (2016), Sabsabi has filmed a colosseum-like football stadium at the moment rugby league fans rush onto the field. The green circle of the field is awash in bodies; his long camera shot makes the human figures seem like a frantic colony of ants (figure 10). What causes the rush of bodies is unclear. The ambient sound carries a distant screaming from the collective shouting of excited fans. The screaming in Sabsabi’s video is haunting, and seeing bodies running en masse lends the association of something having gone awry. For example, it is possible to draw parallels between Sabsabi’s scene and that of people frantically running from the Manchester Arena in the terror attacks at Ariana Grande’s concert.

Since 2001 Sabsabi has travelled extensively between Sydney and Lebanon among other countries in the Middle East. His work engages with the region but perhaps like many of the artists discussed here, his work is strongest when it reflects his unique insights and experiences of the dichotomous aspects of cultural and political life in Australia.

JOANNE SAAD

Joanne Saad was born in 1969 in Sydney, Australia, and is of Lebanese heritage. Like Sabsabi, Saad’s practice draws on her own experiences of cultural displacement in Australia. These experiences offer her a starting point from which to engage with and collaborate with others. Currently, Saad lives and works in Oman researching and developing new work on the Bedouin of the Middle East and North Africa. For over two decades she has worked with photography and video in what may be described as expanded portraiture and documentary. Her photographic and video portraits draw on the intimate connections she has with the communities she collaborates with. This collaborative process is an integral aspect of her working in many diverse communities.

The strength of Saad’s practice has been her connection to the people who inhabit the outer suburbs of Sydney’s cultural landscape. Recent projects were situated in suburbs such as Blacktown and Bankstown where many migrant and refugee communities settle. Often her subjects are from Arabic, African, or Asian communities that were displaced by war and other political conflicts as well as those who migrated to Australia in the 1950s for mostly economic reasons. As a result, her work is inherently political, addressing issues of migration, displacement, and the racial politics that have often and continue to trouble Australia.18

She strives to collaborate with her subjects and succeeds in depicting them as individuals who form part of a social cultural group that sit outside of the mainstream of Australian cultural life that is dominated by Anglo traditions, histories, and identities. She aims to create connections with people that open up possibilities for personal responses to the abovementioned issues.19 This was particularly evident in her collaborative project titled Family Portraits (2015). Urban Theatre Projects commissioned this work for Bankstown: Live, a celebrated community event that was part of Sydney Festival in 2015.

In Family Portraits, a suburban street in Bankstown was transformed for four hours into a stage. Saad set up a backdrop by which she gathered and engaged with her photographic subjects. On this street-cum-stage, the interior of the family’s homes was reproduced, so while they were seated outdoors they were also in front of a photographic simulation of the inside of their house.

The family being photographed invited the audience into the reproduction of their homes―to sit on their furniture, beckoning conversation and welcoming them into the scene and onto the stage to have their portrait taken as “extended” family. The most compelling example is a portrait called Georgia, Uncle Steve and Christos (figure 11). It depicts an older Greek couple in what appear to be the armchairs from their actual living room. They sit in front of a backdrop depicting the timber veneer archway in their would-be living room and in front of them is their framed wedding portrait. Between them sits Uncle Steve, an indigenous man who is dressed to perform a traditional smoking ceremony and adorned with face paint and gum leaves under his armband.20

The incongruity of these subjects―old Greek couple and indigenous Aboriginal man―is rarely pictured. From the perspective of Australian photographic history these diverse cultures are scarcely represented in a visual history dominated by colonial stories and depictions of beaches and sunbathers, bushrangers and bridges―these people are Australia’s marginalized subjects.

Another example (figure 12) is the African family portrayed alongside an Anglo couple where a blonde woman has her arms wrapped around the shoulders of an Asian boy. These examples demonstrate Saad’s interest in race and the depiction of racial appearance in portraiture. Her works do not, however, reinforce the differences often played out in the Australian media, but rather, by bringing diverse people from diverse communities together, highlight what people have in common. In describing this work, Saad states:

I am fortunate that I have met so many amazing people who have welcomed me into their homes and shared their personal stories. It is this experience that I wanted create for Bankstown: Live―bringing private worlds into the public space and connecting people with one another through intimate moments.21

The strength of her work is the depiction of a nuanced and collaborative approach to portraiture that often explores personal experience. My introduction to her work focuses on this strength of “closeness.” She has often elaborated on the intimate nature of making portraits and the close bonds she forms between herself and the subjects she photographs. Describing her own work, the artist states: “The photographs and video works lay bare the everyday through the people who actively participate in its creation.”22 This view sits in opposition to the history of ethnographic portraits: rather than position herself as photographer and powerful onlooker, Saad seeks collaboration with her subjects. Instead of depicting them from the vantage of an outsider, she approaches portraiture first by getting to know people, meeting with them, talking to them, and hearing their stories. Her process of making portraits, whether photographic or video, is empathetic, and in it she exercises a “democratic engagement with people and social groups.”23

This “closeness” is perhaps best demonstrated in the work Remembering (2014). Saad created a collection of sixty photographic and video portraits with residents of Blacktown in Western Sydney (figure 13). The works portray various subjects conversing with the artist (who was offscreen), disclosing private stories full of hope, joy, and sadness. Many face the camera head-on and close up, making them appear incredibly vulnerable. Their stories are told willingly and one suspects they must trust Saad as the recipient of their recollections. The confessional style of this work is a haunting antithesis to the confessional videos that confront us in reality television. Rather than mocking her subjects, Saad portrays their humanity alongside her own, to reveal the emotional life of stories and memories that bring us closer together.

HOSSEIN GHAEMI

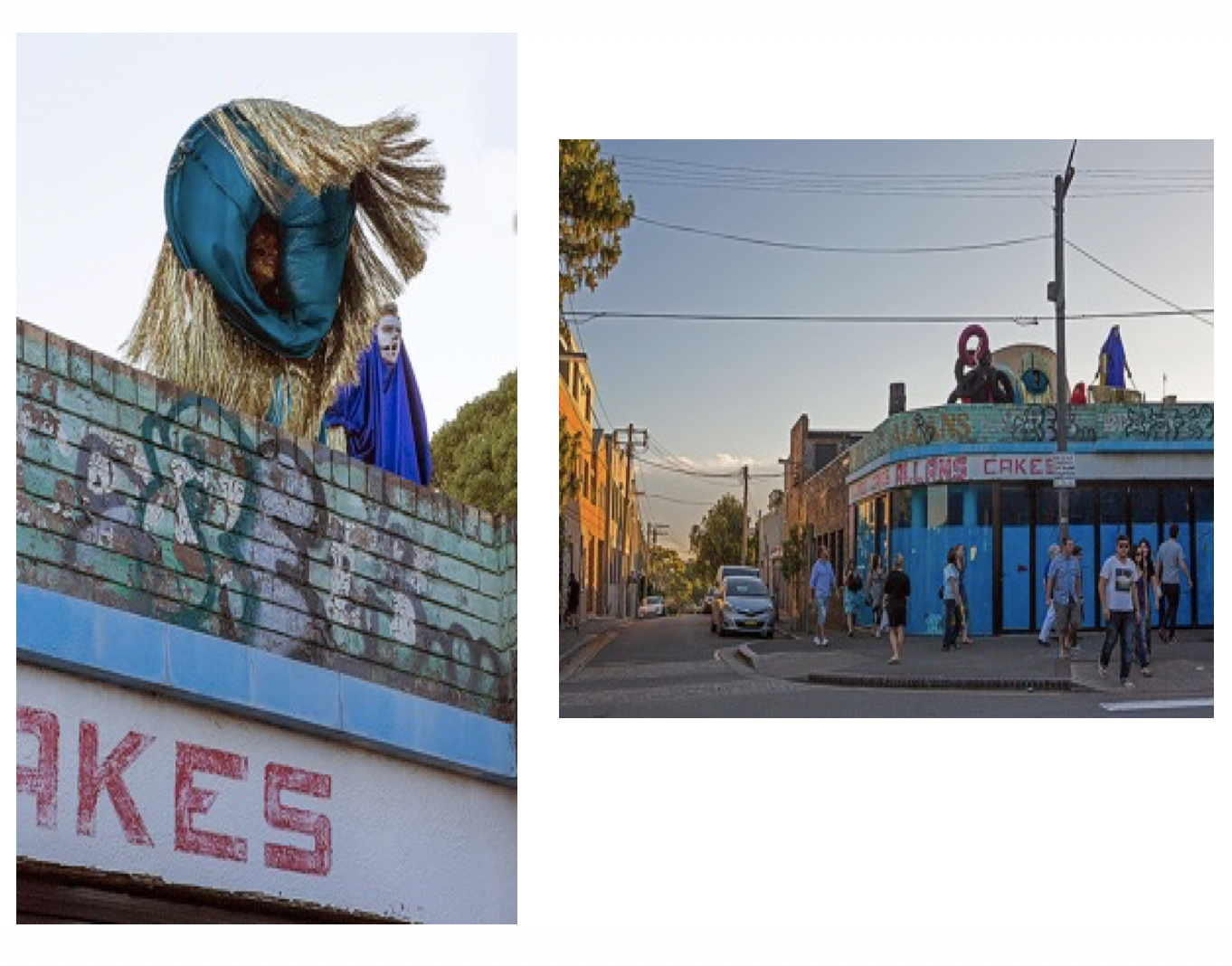

Hossein Ghaemi was born in 1985 in Tehran, Iran, and migrated to Australia in 1987. He is a Sydney-based performance and video artist who assembles characters, costumes, and choirs that use poetry and song to perform “ritual” dances. Ghaemi’s creative abilities extend across mediums, displaying a multifaceted approach to art making that sees him choreograph chaotic dances, write music scores and lyrics, design costumes and sets, and make pseudo-ceremonial objects and paintings.

The most intriguing of his performances use the human voice as a material. His choirs are made up of invented characters that are so surreal they border on the psychedelic. One example of this is the eccentrically titled work, The Deficient of Solution Development: Quizzing Makes Remedy (figure 14). In 2013 Ghaemi formed this choir to perform at the Tiny Stadiums Festival in Sydney. Its members “battled” each other through strange nonsensical sounds.24 The performance was made stranger by the fact that it was executed not in a theater or on a conventional stage but on a rooftop of a vacant inner-city shop in Sydney. To the community that formed his spontaneous audience, his characters appeared like garish specters.

Ghaemi’s choirs are not ordinary choirs: costumed elaborately in layers of upholstery fabrics, including fringe tassels characteristic of decorative curtains, some are stuffed with wadding and appear blown up, others are distorted and monstrous or appearing to be members of the Ku Klux Klan gone awry (figure 15). Their identities are often concealed under thick gold, silver, and black face paint.

His work draws on the mysticism inherent in the song and poetry of his Persian and Turkish heritage. The references to this heritage are amplified by the artist’s consistent use of veiling and concealment. His characters are often shrouded beneath elaborately designed and decorated costumes, turning them into magical singing “surrealist” creatures that are often “whirling” in a style that recalls Turkey’s whirling dervishes. With these features, it is not surprising when he describes his work as “coming from dreams and his unconscious.”25

Recently, Ghaemi has employed video as a way of preserving his otherwise ephemeral performances. His recent video work, Angry Flower (2015), is the first iteration of a series which employs his mother as the central performer (figure 16). Playing herself in one scene, she is seated at her kitchen table smoking a cigarette to the sound of Arabic drumming. A pot of water is boiling and bubbling on the stove to a fantastical soundtrack. It appears to have magical properties that transport them in an instant to a suburban Australian park. Full of large ghost-gums (eucalyptus trees typical of the Australian landscape), the park is converted into a stage for the main scene showing his mother, now a shamanic figurehead, leading a quasi–whirling dervish performance while sucking on a long drinking straw and battling the strength of a powerful wind.

This video encapsulates Ghaemi’s many creative endeavours in terms of filming, soundtrack, painting, script writing, and choreography. Central to both his live and recorded work is the promise of a narrative that never truly unfolds from beginning to climactic end: the audience are always left wondering, guessing, and imagining what will happen next. Ghaemi’s stories are left open, beautifully ambiguous, and like his characters, never fully revealed.26

Like Armanious’s early use of Arabic objects and forms, Ghaemi at times draws on the aesthetic traditions of his Persian and Turkish heritage, transforming cultural performances into kitsch spectacular. In this way, Ghaemi’s work does not overtly address sociocultural politics and yet I find it irresistible to see the cues that point to cultural signifiers that are familiar to my own Lebanese-infused childhood. The Arabic drumming and the kitchen scene depicting Ghaemi’s mother in Angry Flower evokes to me the years spent with my own grandmother drinking Lebanese coffee to the sound of the Arabic radio, with Australia as our backdrop. In this way, Ghaemi’s work is both accessible and magical, both of the allure of a Turkish bazaar and of suburban Australian life. A distinctly strange pairing.

CIGDEM AYDEMIR

Cigdem Aydemir was born in 1983 in Sydney, Australia, and is of Turkish heritage. Aydemir’s practice combines performance with video, sculpture and installation. Her work considers the history and politics that besiege Muslim identity in Australia particularly in relation to gender and religion.

The focus of her performances and video work is often herself depicted as a veiled woman. Many of her video performances interrogate the social and political repercussions of veiling. She uses irony to question the West’s fear of Islam and the way this fear is directed at the burqa specifically.27 Veiling of women (veiling herself) is often synchronized with the veiling of obscure objects such as children’s swings in public parks, shopping trolleys, bicycles with carriages, or public statues. This approach recalls Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s wrapping of famous monuments, but in Aydemir’s approach paradox, irony, and humor infuse the aesthetic act with political meaning.

The compelling work Bombshell (2013) won her the Redlands Konica Minolta Art Prize in the Emerging Artist category. In this single channel video Aydemir re-performs Marilyn Monroe’s famous scene from The Seven Year Itch (1955), in which Monroe wore the iconic white dress that is lifted by the breeze from the subway vents, forcing her dress to billow and reveal her legs. Aydemir recreates the scene donning a black burqa to the soundtrack of bombs blasting (figure 17). In her recreation, the burqa is like a huge deflated parachute billowing like a black flag, taut around her head but dancing around her body. The effect of billowing fabric is similarly explored in the video Whirl (2015). In this, she overtly mocks hair shampoo advertisements. Wearing a face-hugging magenta scarf, she pretends to blow-dry her hair, which in this case is a scarf. The scarf again swirls like a flag in the wind―a harmless and beautiful tactile object (figure 18). This has a transformative effect on an object that has otherwise been stigmatized by the Western media’s portrayal of the veiled woman as someone to fear. The artist quite humorously describes her intent in this work. Exploring the “liberating” promise of shampoo commercials, she notes her own personal experience as a veiled and then an unveiled Turkish woman.

As a personal anecdote, the encouragement I received immediately after unveiling led me to believe that removing the veil should be a shampoo commercial–type experience, which it was not. Whirl explores that memory while throwing into question the inherent assumptions between unveiled/liberated/beautiful and veiled/oppressed/abject.28

Aydemir understands intimately the politics of veiling because she wore a hijab herself for ten years. As a result, her work successfully reveals the current paranoia associated with contemporary representations of Islam and the veiled woman. In response to fear and paranoia, Aydemir attempts to “demystify the other” by inviting her audiences to take part in her performances, welcoming them into her veil.29 For example, in Extremist Activity (ride) (2011), she rode her bicycle around the city and invited people to climb under her veil-cum-carriage (figure 19). The artist notes: “The Extremist Activity series was, in part, a response to the Islamophobic fear of Muslim women who could be hiding ‘anything’ under their veils, as well as a tongue-in-cheek look at the stereotype of Muslim extremeness.”30

In one of her most powerful works that refers to the politicized nature of being Muslim and the contested territory of the Australian beach, Aydemir performs a tongue-in-cheek performance recalling the iconic ’90s television series Baywatch. In I Won’t Let You out of My Sight (2015), she performs wearing a red burkini (her running and the color of the burkini is deliberately reminiscent of Pamela Anderson’s revealing red swimsuit); she is filmed running the length of Maroubra, Bondi, and the infamous Cronulla beaches (Cronulla Beach was the site of racial tensions between local Anglo gangs and young Lebanese men in 2001).31 On her shoulder she carries what appears to be a life-saving device that doubles as a boom box blasting the theme music of Baywatch (figure 20).32

Her work is undoubtedly informed by her identity as an Australian Muslim woman of Turkish heritage. The strength of her work is that while remaining critical of both gender and religious stereotyping, she has an innate ability to provoke laughter from her audience (as I have witnessed firsthand) and perhaps for this reason, her work is more important now than ever.

RAAFAT ISHAK

Raafat Ishak was born in 1967 in Cairo, Egypt, and migrated to Melbourne, Australia, in 1982. His practice can loosely be described as painting although he works across many disciplines including sculpture, drawing, and installation. Irrespective of medium, his work is distinguished by a systematic approach to creating imagery and objects that are simultaneously figurative and abstract. He adopts an exacting approach to producing serial paintings that are restricted to what he calls the “bureaucratic sizes of a1, a2, a3, a4.”33 This systematic aesthetic is exaggerated by the material limits he places on the work. For example, the artist tends to use MDF, a manufactured timber product that has an incredibly smooth finish and is quite appealing as a painting surface.

His use of “systems” not only governs his material methodology but also his conceptual approach. His imagery alludes to strict conceptual parameters that suggest an instruction may have provided the logic for their existence. For example, in a politically motivated work, Responses to an Immigration Request from One Hundred and Ninety Four Governments, (2006–2009), Ishak composed and sent a letter to 194 governments requesting citizenship.34 He then produced an epic series of 194 pastel-colored abstract paintings, each a faded version of one country’s flag, inscribed with a flourish of Arabic text representing some of the government’s responses (or lack thereof) to his request for citizenship (figure 21).35

The strength of his practice exists in the dialogue he creates between politics and art. Ishak’s practice consistently asks questions about the contemporary state of the world: citizenship, nationhood, home, cross-cultural identity, and how these issues may become manifest in dialogue with art and architecture. Many of his projects such as Nomination for the Presidency of the New Egypt (2012), and Congratulatory Notes on Ubiquity and Debacle (2011), speculate on these issues, but never didactically; rather, his works operate as games where there are unseen rules and systems in place, and occluded visuals to decode.

Politics operates in his work as a series of speculative creative gestures that concurrently exist in the act of making art. Through these gestures, his acute knowledge of art history is evidenced. His work also demonstrates art’s long-standing relationship to politics.36 This knowledge is embedded in projects that recall radical works such as Malevich’s Black Square (1915). For instance, in Half a Proposition for Banner March with Black Cube Hot Air Balloon and Mount East (2012), the artist collaborated with Tom Nicholson on an expansive project that produced sculptures, banners, and performances. In one sculpture (figure 22), a black cube recalling both Malevich’s square and the Kaaba in Mecca, the artists have pulled apart and dissected the “sacred” form of the black cube to reveal its augmented interior. In other works, he references Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (1912), and in his more recent collaborative work he draws on de Chirico’s paintings.

The artist also revealed that he uses disparate sources to collect his imagery. These include “department store catalogues, brutalist architecture, staircases, military insignias, children’s books, animal skeletons, to name a few.”37 In a recent exhibition titled 1977 (2017), Ishak presented such imagery in a suite of nine paintings on MDF (figure 23). In this series he left the MDF un-primed and its timber-colored background offers something like a sandy desert scene containing an array of subjects such as a camel, a big brown bear, an overturned car, a decorative dagger, classical Greek statuary, a winding staircase, and the Union Jack. These diverse subjects are carefully illustrated and painted in colors that recall military camouflage; browns, greens, and grays that are muted and muddy. The style is cubist and the subjects are consistently concealed under multiple layers of imagery that make aspects of the paintings unidentifiable.

His paintings have often reminded me of the methodical children’s activity color-by-number. In Ishak’s work, however, it is a complex system that is left open and unfinished. This open system of painting requires the viewer to seek out the concealed and camouflaged subjects occluded beneath each representation. The strength of his work lies within this paradox to both picture the world and stubbornly conceal it.

FASSIH KEISO

Fassih Keiso was born 1956 in Syria and has lived and worked in Melbourne since 1993. He describes the influence of having lived in both countries for significant amounts of time as informing the cross-cultural themes characterizing his interdisciplinary practice. His work employs various media from painting to photography, performance, video, and installation. Each work is governed by a central idea that usually links Arabic contemporary life, culture, and politics with broader global issues.

Keiso’s practice is very much embedded in the cultural and political life of the Middle East. This is interesting in relation to the other artists discussed here. This is perhaps owing to the fact that he lived a significant part of his adult life in Syria. His works regularly examine the encounter of Eastern and Western ideologies and the divergences between them.

In his early work from the ’90s and into 2000 he reflected on the tension between Middle Eastern and Western perceptions of the body and sexuality (arguably a problematic task for a male artist when this involves the portrayal of women). For example, in Curtain for My Window (1999–2000), he utilized photographic technology to manipulate and reproduce parts of the female body into a recurring pattern suggestive of both traditional Islamic patterns and the grid of Western geometric abstraction (figure 24).

More recently, in a work shortlisted for the 2016 Blake Prize titled The Last Supper Not (Why Not?) (2016), the artist reimagined the biblical scene of Jesus Christ and the Last Supper. In his version the disciples are young veiled Islamic women (figure 25). The work visually conjoins Christianity with Islam in order to demonstrate what for Keiso has represented a cultural union rather than ideological differences. The artist notes: “the Last Supper is an attempt to embody the two religions . . . culturally, I feel I belong to both of them.”38

For his current and ongoing project, Creative Responses to the Syrian Crisis (2016–), Keiso returned to his homeland and undertook a period of research to examine what is happening to his country. The work aims to reflect on historical theories of war and dispersion that impact Arabs geographically, physically, and spiritually.39 In this work, he continues to extend art’s continuing dialogue with war and conflict. Keiso does not in any way romanticize war; rather through his performances, photographs, and videos one gets the feeling he is trying to understand it. His “creative responses” demonstrate the artist’s creative acts as a form of activism in relation to the Syrian crisis. As Keiso notes:

I started working on this project on March 31, 2016; a few days after the Syrian government reclaimed Palmyra from ISIS, I visited the site and its museum with the purpose to document the current situation of the ancient city. This project is a reflection of what I witnessed during my visit.40

Women regularly feature as subjects of his work. This has caused him some strife. For example, at Gertrude Contemporary in Melbourne 1998 he exhibited They Shoot Belly Dancers, Don’t They? (figure 26). The artist was threatened with court action from some of the women who posed as belly dancers for the work.41 He described the situation as a cultural misunderstanding. Ironically, his intent was to highlight cultural misinterpretations and reappropriations of Middle Eastern rituals to underscore the tensions between current Eastern and Western perceptions of the body and sexuality. Writing on this work, the artist notes his ongoing frustration with making art in Australia:

While Westerners are familiar with belly dancing, most have no correct information on the subject and few ideas about the conflicts that the Arab world faces. Educating Australians about the culture I came from became my main motivation in my artwork, which was also a result of the harassment I faced.42

Women still appear as ongoing subjects of his imagery; he does not shy away from this despite the criticism he has received. For instance, in his current project, he interviewed a number of female Syrian fighters who have formed a group to protect their communities. Their position is complicated by their two-fold struggle to guard their neighborhoods while simultaneously fighting for equality with the local male combatants.43 The nature of this twofold struggle serves to define Keiso’s practice as a whole. The artist sees his role as one that attempts to bring two divergent worlds together, the two worlds he himself inhabits. Despite various ideologies on the body, religion, culture, and war, Keiso’s work seems to effortlessly and at times provocatively synthesize and picture incongruent mind-sets, objects, and people.

CONCLUSION

By introducing the work of seven contemporary Australian artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora I have intended first and foremost to bridge a gap, hoping to contribute to supporting contemporary art in Australia and its exposure nationally and internationally, as well as in a scholarly context. However, in doing this I must also acknowledge my discomfort. I am only too aware that I am participating in a form of categorization, or the pigeon-holing of my peers as artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora. This categorization connotes “not the mainstream.”

Why am I uncomfortable with this? Largely, there is a tendency in Australia (and this is not unique to Australia) to classify artists from non-Anglo backgrounds into racial categories: Arabic artist, Asian artist, and Indigenous or Aboriginal artist. These are just three of the most common examples.44 This tendency is both one that is put upon us and one which we utilize ourselves. I must confess that my discomfort with such categories arose early in my own artistic career (1999–2005, coinciding with the 9/11 attacks in the United States) when there was a considerable focus on my cultural heritage resulting in a misinformed and limited framing of my work as a photographer. What I encountered was an exasperating situation that despite the imagery I was producing, which for the most part had little to do with my cultural upbringing or racial ancestry, I was too often referred to as the Other―a Lebanese-Australian artist. While my Anglo-Australian peers could seemingly enjoy the freedom of being “artists,” I was very much a “Lebanese-Australian artist.” While I have attempted to resist such narrow parameters over the past twenty years, I have also recently come to ask questions about my discomfort. Thus, I have sought the views of my peers and have attempted to come to some acceptance of the vexing issue of othering artists and their art, as well as othering ourselves.

Through email correspondence and phone conversation I asked my peers directly: Does being from the Middle East inform your practice? Why and how? And is it inherent for artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora to make art as a form of “activism,” art that is sociocultural and political?45 Many simply stated, yes, it did inform their practice, and that this occurred because they made art from direct experience and that autobiographical experience was very much informed by their connection to the Middle East, its politics, rituals, conflicts, religions, and cultures. They also noted the arts’ longstanding relationship with politics. Thanks to the straightforward responses given by the seven artists represented here, the nature of othering that can occur professionally for artists who are non-Anglo (but are Australian), can perhaps be interpreted not as a problem (as Armanious describes it), but rather as an opportunity. In other words, making art informed by one’s life and one’s political persuasions is at times necessary.

The seven artists discussed in this article represent a wide range of issues and practices. Their works are conceptually complex, employing methodologies centered on both aesthetic and formal concerns, all the while having something significant to say about the local and global issues that fundamentally affect us all whether we live “remotely” in Australia or in the intense and dense continents that make up the rest of the world. Further, Australian artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora have a central role to play as activists, as voices of reason, and healers of racism and racist views and policies. Anti-Muslim sentiment is common in Australia and is too often both ignored and exploited by politicians in the effort to win popular votes and media attention.46 In this regard, the seven artists discussed here, among others, continue to have an important role to play in Australian cultural life.

Finally, I’d like to close this article with a noteworthy response from one of the artists (who did not want to be named) who replied to my above questions resolutely stating “that many artists make work that draws on their cultural background and politics. This is not unique to artists from the Middle East.”47 The artist also noted that perhaps my question should ask, How―or should―being an Australian inform an art practice?48 Now that would make a stimulating discussion.

NOTES

Documenta is a major international contemporary art event, held every five years in Kassel, Germany.↩︎

The Australian art critic John McDonald noted somewhat cynically: “The notion of greater inclusiveness surfaced again in the 2002 Documenta, put together by Nigerian-born curator, Okwui Ekwezor. This show included artists who originated in many exotic locations, although they all seemed to live in New York or Paris or Berlin, just like the curator. See more on McDonald’s website: “El Anatsui,” John McDonald, 4 February 2016, http://johnmcdonald.net.au/2016/el-anatsui/#sthash.RYGyZkW8.dpuf.↩︎

This is not unique to Australian artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora. Very few Australian artists succeed in achieving international recognition and visibility. This invisibility was recently evidenced in the 2017 Venice Biennale’s major curated exhibition in the Arsenale. This exhibition included work by over a hundred artists from every corner of the globe and yet failed to feature any artists living and working in Australia or New Zealand. There was, however, one artist, Adam Nankervis, who lives and works in London and Berlin but was born in Australia. Australian artists are more likely to achieve international success by way of inclusion, visibility, and representation if they relocate to European or North American art hubs. Recently, this can be seen with two Australian artists who live in Europe: Angelica Mesiti who relocated to Paris, and David Noonan who relocated to London.↩︎

Five of the artists migrated to Australia from the Middle East, while two were born in Australia and are children of Middle Eastern migrants.↩︎

Admittedly, this is not an extensive survey of Australian artists from this diaspora. Other noted artists include Nasim Nasr, Marian Abboud, Nuha Saad, and Rushdi Anwar, as well as Khadim Ali, who is a refugee from Afghanistan.↩︎

Despite the recognition these artists have enjoyed in Australia, there is very little critical writing to support their practices. As a result I have undertaken this research by speaking with the artists directly and asking them to answer a number of questions via email. Thankfully many represent themselves well through their websites that have provided a wealth of information concerning exhibitions, artist statements, and conceptual rationales.↩︎

Exhibitions and Events, “Walid Raad: October 12, 2015–January 31, 2016,” MoMA, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1493.↩︎

“Emily Jacir: Europa,” Whitechapel Gallery,

http://www.whitechapelgallery.org/exhibitions/emily-jacir-europa/.↩︎

“Hany Armanious, interviewed in 2013 for MCA Artist Voice,” YouTube video, posted by MCA Australia, 5 June 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QdS50YRibtM.↩︎

Hany Armanious, Morphic Resonance (Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2007).↩︎

Email correspondence with the artist, 1 June 2017.↩︎

Hany Armanious and Anne Ellegood, Hany Armanious: The Golden Thread (Sydney: Australia Council for the Arts, 2011).↩︎

“SBS STVDIO documentary – Hany Armanious – The Golden Thread,” YouTube video, posted by Australia Council for the Arts, 7 June 2011, 02:21; 02:07, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wim3nVfy0KQ.↩︎

“SBS STVDIO documentary,” 02:24.↩︎

Ibid., 06:43.↩︎

This exhibition was curated by Ihab Shalbak at Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre, Western Sydney, 10 March–29 April 2001. See review, Kiersten Fishburn, “East of Somewhere,” Artlink, June 2001.↩︎

William Verity, “A Day in the Life of Prize-Winning Artist Khaled Sabsabi,” ABC, 11 November 2014, http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/encounter/a-day-in-the-life-of-prize-winning-artist-khaled-sabsabi/5882352.↩︎

For a comprehensive study of race politics in Australia, see David Marr, “The White Queen: One Nation and the Politics of Race,” Quarterly Essay 66 (March 2017).↩︎

“Joanne Saad,” Joanne Saad, 2018, http://joannesaad.com/about/.↩︎

Reconciliation Australia defines a traditional smoking ceremony as “one of the most significant ancient ceremonies performed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The ceremony involves smouldering various native plants to produce smoke which are believed to have cleansing properties and the ability to ward off bad spirits.” See “Holding a Smoking Ceremony,” accessed 18 June 2017, http://www.reconciliation.org.au/nrw/get-involved/hold-a-smoking-ceremony/#.WUthSsbwdE4.↩︎

Joanne Saad, “Family Portraits,” Urban Theatre Projects, 2015, http://urbantheatre.com.au/past-projects/family-portraits/.↩︎

“Remembering,” Joanne Saad, 2014, http://joannesaad.com/photography/remembering/.↩︎

“Joanne Saad,” Joanne Saad, 2018, http://joannesaad.com/about/.↩︎

“Hossein Ghaemi: Tiny Stadiums 2013,” YouTube video, posted by Das Platforms, 2 November 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RkwMLCfTVrE.↩︎

“Hossein Ghaemi: Tiny Stadiums 2013.”↩︎

Iván Muñiz Reed, “Hossein Ghaemi: Wide Blue Yonder and the Almighty Hoof (A painting show!),” news release, The Commercial, 25 July 2014–23 August 2014, http://www.thecommercialgallery.com/uploads/FXSSE9D-Muniz%20Reed%20Hossein%20Ghaemi%20WBYATMH.pdf.↩︎

Cigdem Aydemir, “Image and Voice: Muslim Women in Contemporary Art,” (MA thesis, Sydney College of the Arts, 2015), http://cigdemaydemir.com/aydemir_ca_thesis.pdf.↩︎

“Whirl,” Cigdem Aydemir, Selected Works, video, 2015, http://cigdemaydemir.com/whirl.html.↩︎

Lola Pinder, “Creative Paddington: Cigdem Aydemir,” Australian Centre for Photography, 2018, https://acp.org.au/blogs/news/cigdem-aydemir.↩︎

“Extremist Activity (ride),” Cigdem Aydemir, Selected Works, photo of performance, 2011, http://cigdemaydemir.com/EA_ride.html.↩︎

In December 2005, the Cronulla riots took place in response to simmering tensions between young Lebanese men and the local white population. On the day of the riots Australian “patriots” took to the beach calling it “bash a Leb day.” Anyone who appeared to be Lebanese was set upon by angry mobs of white people bearing Australian flags and anti-Lebanese, anti-migration, and anti-Muslim placards. This took place in the beachside suburb of Cronulla in Sydney’s south. For an in-depth study see Cronulla Riots: The Day That Shocked the Nation, video documentary, SBS, 2014, http://www.sbs.com.au/cronullariots/documentary.↩︎

For a comprehensive discussion of this work see the exhibition catalog. Rachael Haynes and Christopher Handran, “Cigdem Aydemir: I Won’t Let You out of My Sight” (Brisbane: Boxcopy Contemporary Art Space, 2015), http://cigdemaydemir.com/Cigdem%20Aydmir%20Exhibition%20Catalogue.pdf.↩︎

Email correspondence with the artist, 5 April 2017.↩︎

To read this letter see Raafat Ishak, “Responses to an Immigration Request from One Hundred and Ninety Four Governments,” Sutton Gallery, 17 September 2009–17 October 2009, http://www.suttongallery.com.au/exhibitions/exhibitioninfo.php?id=65.↩︎

Wes Hill, “In Focus: Rafaat Ishak; The Merging of Politics, Materials and Metaphysics,” Frieze, 23 April 2014, https://frieze.com/article/focus-raafat-ishak.↩︎

Wes Hill, “In Focus: Rafaat Ishak.”↩︎

Email correspondence with the artist, 5 April 2017.↩︎

Email correspondence with the artist, 14 April 2017.↩︎

Fassih Keiso, “Fassih Keiso,” Fauvette, exhibition catalogue, (Sydney: Sydney College of the Arts, 2016), 51.↩︎

Email correspondence with the artist, 14 April 2017.↩︎

According to Keiso, the women assumed he was photographing them in a “straight,” documentary style. They did not understand that the work was going to be digitally manipulated and abstracted. As a result, the court case was potentially about copyright issues and whether he could reproduce the imagery of the women in such a way. The case was eventually dropped but left the artist weary. Email correspondence with the artist, 27 June 2017.↩︎

Email correspondence with the artist, 14 April 2017.↩︎

“Creative Responses to Syrian Crisis,” Sydney College of the Arts, accessed 29 May 2017, http://sydney.edu.au/sca/news/2016/creative_response_syrian_crisis.shtml.↩︎

One reason for this “othering” may be the administrative requirement that funding bodies, museums, and other cultural organizations meet diversity frameworks to ensure artists from cross-cultural communities receive a share of funding and exposure.↩︎

The same question can be asked of contemporary Asian art, Indigenous art, and African art.↩︎

On 14 August 2018, Senator Fraser Anning called for an end to Muslim immigration and a return to the White Australia Policy. Using the Nazi phrase “final solution,” he called for an end to Muslim immigration. There was a huge backlash in the Australian Parliament; Jewish parliamentarians were particularly critical. Both sides of government condemned Anning’s statement. See Louise Yaxley and Stephanie Borys, “MPs Condemn Fraser Anning for Controversial Maiden Speech Which Called for a Ban on Muslims,” ABC, last updated 15 August 2018, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-08-15/fraser-anning-condemned-for-using-phrase-of-nazi-germany/10121844.↩︎

Email correspondence with the artist, April 2017.↩︎

Email correspondence with the artist, April 2017.↩︎