Martine Natat Antle

Women Challenging the Norms in the Arab Diaspora: Body Talks in Contemporary Art

At fifteen I was widowed.… I was illiterate. You must understand, it’s important not to be afraid to be different.

―Chabia Talal

Before embarking on the production of the artistic expression of women of the Arab diaspora, and in particular how they represent the body and sexuality in art, it is first important to foreground representations of the body by women in Western art, because their production also continues to be relegated to the margins of art history. On a large scale and globally speaking, both in the East and West, women have rarely participated directly in the production of art history. Yet, women in the West, who had up to the 1980s been all but excluded from the art world, have challenged us to rethink and recontextualize the representation of the body. Most often they have found identity and affirmation through the desire to differentiate themselves from the long history of masculine production of art. As Marie-Jo Bonnet observes about nudity in Western art: “The nude is thus one of the greatest conquests of women artists of the twentieth century.” However, rather than following the path of men, Western female artists reverse the connotation through an increasingly complicated critique of masculine voyeurism and exploitation of women’s bodies.1

The artistic project of Western women artists who tackle the body is complex, in that it becomes a project of re-inscription first of the body, then of eroticism and sexuality in art, notions that have been monopolized by Christian religious art since the Renaissance. The body has been reinvested and reappropriated by male artists, thus perpetuating the exclusion of women throughout the history of art. Beginning with the European avant-garde of the 1920s and 1930s, many women denounced the taboos associated with women and their bodies and questioned the social construction of the female body in art. Throughout the following decades, the new feminist theoretical discourses of the 1960s relocated sexuality and sexual practices from the private sphere to the public. More than ever, the liberation of the body found itself at the center of discourse, bringing women artists face to face with many questions, such as how to cast off the masculine yoke, the patterns of male domination, what Foucault called the “law of prohibition”;2 and how to represent the body and eroticism in a new way so as to reverse masculine hegemonies.

Numerous women artists set out on this quest for a new language, not only in the West, but soon thereafter in the Arab diasporas relatively unknown to Western institutions. What characterizes these artists of Arab descent, the majority of whom have trained and currently live in the West, is that in opposition to their Western counterparts, they live away from the homeland, in exile. This particular position allows them to articulate “a plurality of vision.”3 As we shall see here, these cross-cultural artists situated in dialogue with the East and West open a novel liminal and fertile space of communication. This “in-between” cross-cultural space implies a process of transculturation that challenges, if not erases, the notions of borders and nationhood.

In this essay, I will question to what degree and through what means women artists from the Arab diasporas, who have received little critical attention, deliberately engage—as Easterners—in the challenging of masculine hegemonies.4 More specifically, I will show to what degree these artists create and re-inscribe new configurations of the body and unprecedented body talks in contemporary visual art.5

As African American critic and activist Audre Lorde has so stunningly argued, the search for eroticism is central to all artistic projects. Women artists must initially question the masculine pornographic apparatus that denies women not only eroticism, but also all sexual pleasure. According to Lorde:

Our erotic knowledge empowers us. But this erotic charge is not easily shared by women who continue to operate under an exclusively European American, male tradition. . . . Recognizing the power of the erotic within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world. . . . For not only do we touch our most profoundly creative source, but we do that which is female and self-affirming in the face of a racist, patriarchal, and anti-erotic society.6

In the same spirit of reversing the stereotypes associated with women, and in the same pursuit of visibility for women’s artistic production, women artists of the African and Oriental diasporas take control of the production of their own visual representation, as Salah M. Hassan demonstrated in Gendered Visions: “They are no longer the displaced and subdued objects of a hegemonic (foreign or male) gaze; they have instead become centrally located, active creators who call such a gaze in question.”7 Women artists of Arab diasporas also learn to renew the ties between art, women, the body, and religion, and they thereby thrust the originality of their project onto the international art scene from Europe, the Middle East, and Australia.

A critical overview of women artists of the Arab diasporas who work on the female body is not only intergenerational and transnational but considers several registers of artistic production. Some of the artists considered here are today visible at the global level, while others are not yet as advanced in their career.

It is important to first acknowledge that women artists of the diasporas have taken on a wide range of topics currently at the heart of diaspora studies: the redefinitions of home, displacement, and traumatic memory associated with loss, and the construction of collective identities. It is no exaggeration to say that today Mona Hatoum is a well-recognized pillar in the artistic production of the diasporas when it come to the notions of home and displacement. Some women artists of more recent generations have also been radical and defiant in tackling politically sensitive topics and challenging the constructs of Arabs and of terrorism in the media in the aftermath of 9/11.

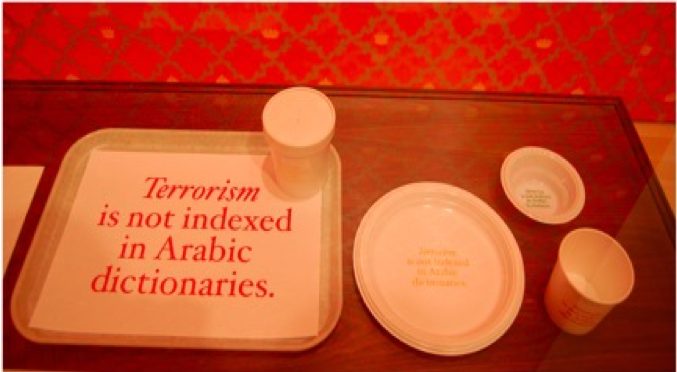

Ghada Amer’s 2005 installation in the Wellesley College cafeteria, “Terrorism” is not indexed in Arabic dictionaries (figures 1, 2), cleverly challenged viewers and customers of this cafeteria to reflect on the etymology of “terrorism,” a word that originated in French history (the Reign of Terror) and a term that contemporary Western discourse applies almost exclusively to crimes committed by Arabs.

This bold installation included the staging of pink and green wallpaper along with paper plates and paper place settings printed with the sentence “‘Terrorism’ is not indexed in Arabic dictionaries.” These place settings, made available for everyone to use, signaled that the use of language may indeed be just a commodity easily used and reappropriated for ideological reasoning.

On the Australian scene, that may open up as a privileged site for art from the Arab diasporas,8 and in response to a comment her father once addressed to her brothers (“Shave your beard off! You look like a terrorist!”), Australian Lebanese artist Cherine Fahd challenges the profiling of Arab men in the media with her project titled, “You Look Like a…” (figures 3–5). Currently working on the visual appearances of Arab men who wear a beard as fashion, she explains,

Images of Arabs that permeate the Western media represent the young bearded Arab-appearing male as the terrorizing Other. I am acutely aware that my evening news only portrays Arabs in these terms, and has been doing so ever since I can remember.9

For her project titled “You Look Like a. . .” she selects beards and “darker” appearances that evoke images of “jihadis” represented in Western media. To confuse viewers and subvert the strategies of racial stereotyping, she deliberately blurs the ethnicities of her Australian models, whose heritages include Arabic, mixed Anglo Arabic, Spanish, and Anglo Celtic. Her portraits also mimic and engage in dialogues with passport-identity photographs. This daring reexamination and confrontation of the profiling of Arabs in today’s societies boldly challenges the ideologies of the media and touches on issues of national security.

This unique positioning of contemporary women artists of Arab descent on the artistic and political scene can be traced back as far as the 1920s with Baya Mehieddine. Although Mehieddine’s artistic journey might seem less radical at first, she pioneered the placement of women and their bodies at the center of pictorial representation. Thanks to her, who first imagined and made women sacred communities visible in the art scene, as well as to Houria Niati, with her deconstruction of Orientalist ideology, a new generation of women artists has set off on a novel path in the development of art that is increasingly garnering international recognition. As we will see here, each one of them, through her own style and with little recognition from art historians and museums alike, invokes the legacy of women from the Arab diasporas.

BAYA MEHIEDDINE (1931–): THE FIRST INSCRIPTIONS OF FEMININE ARAB-MUSLIM ART

Adopted at the age of nine by a French couple living in Algeria, Mehieddine, of Kabyle descent, was a self-taught artist. Introduced to the vanguard artistic milieu in Paris during the 1940s, she was immediately noticed by surrealist writer André Breton and painter Pablo Picasso, with whom she remained in close contact over the years. (In fact, Picasso began his series Women of Algiers in 1954 shortly after their meeting.) In 1947, Mehieddine exhibited at the Maeght Gallery in Paris, which opened in 1945, becoming within two years the most prestigious Parisian art gallery at the time.

Mehieddine’s path is unusual in that she had to reconcile different lifestyles since she led a life atypical of a vanguard artist. To begin with, Mehieddine was a devout Muslim and completed the pilgrimage to Mecca three times in her life. She was also the second wife of an Arab musician and had six children. This traditional dimension of Mehieddine’s private life was an integral part of her artistic trajectory. In fact, Mehieddine’s life is interwoven by years in the private and public spheres. In 1947, Mehieddine entered the public sector with her artistic debut in Paris, becoming a center of attention of artistic life and gaining great visibility from her inclusion in the Dictionary of Surrealism, in which very few women artists were listed. From 1953 to 1961, Mehieddine disappeared into the private sphere when she married, had her six children, and did not paint for nine years. This did not prevent Mehieddine from returning to the art scenes of both Algeria and France in 1960. Her success as an artist became evident when, in 1963, the Museum of Algiers dedicated a room to exhibit her paintings, and again in 1964, when she participated in an exhibit on Algerian painters in Paris at the Musée des Arts. From the mid-1960s to the present, Mehieddine has been visible simultaneously on the Algerian and the French art scenes.

Mehieddine has always remained mysterious about her artistic intentions and is well known for her declaration, “I do not know, I feel.” Yet she clearly expressed her intention to move away from Braque or Matisse’s colors and to explore instead the turquoise blues and Indian pinks of Kabyle women’s traditional clothing. In her work, she stages her own personal mythology and women take center stage in her canvases.10 Women populate the natural world, cohabiting alongside birds, fish, and plants. Female bodies and other objects form intricate, decorative, and rhythmic patterns reminiscent of Arabic calligraphy, Islamic art, and Oriental carpets. These patterns give birth to floral and foliate figures. The women’s faces are indistinguishable from the white background and are delineated by the shape of an eye, an eye that resembles an inverted letter H in Arabic. It is interesting that, when learning to write the Arabic letter H, children are told to draw an eye. The letter H in Arabic also denotes a call for attention. Mehieddine’s representation of the female eye in the shape of an inverted H suggests an alternative mode of seeing and of reading, an alternative to art produced by men, and to colonial representations of Oriental women. From this perspective, the art of Mehieddine resists conventional Western categories of art in spite of the fact that she has been exoticized and labeled by many Western writers, notably André Breton, as a surrealist or “naïve painter.” A true pioneer, she innovates and opens the door to future generations of women artists, for by populating her canvases with female characters, she resituates women and their bodies at the center of representation in an exclusively feminine universe:

From there, this mythical flora and fauna, these women with their finery woven with flowers, dresses, beautiful objects that lend a hedonic quality upon life. This winged freedom, which brings to mind a world of angels, makes signs, recounts a fable, an allegory, a secret memory, a phantasmagorical story as told by an enchanted storyteller.11

Mehieddine’s art bears evident traces of a transitory phase for Arab-Muslim art, which inscribes itself for the first time in a feminine tradition, and which also places itself at the intersection of calligraphy, arabesque, and interlacing motifs relevant to the pre-Islamic Arab artistic tradition. However, at the same time, in relying upon scenes representing human figures and thus on motifs of Western painting, Mehieddine takes the first steps towards what could be called a hybrid feminine aesthetic. These first steps towards a cross-cultural investigation of the feminine open the door to several generations of women artists to come. Each generation will bring its particular concerns, expressions and voices of rebellion. From this standpoint, Houria Niati challenges Orientalist art and its submissive portrayal of Oriental women in her artistic production.

HOURIA NIATI (1948–): CASTING OFF THE VEIL OF ORIENTALISM

Born in Algeria, Houria Niati was arrested at age twelve for writing anti-colonial slogans on walls. She studied art in Algeria and in 1977 moved to London where she continued her training at Croydon Art College. Although she has lived in London since the late 1970s, she grew up with and witnessed firsthand the Algerian Revolution; it is through these experiences that she directly confronts Western Orientalism in her work and rewrites Algerian women’s history. Her series of multimedia pieces titled No to Torture was first exhibited in England in 1990, accompanied by audio recordings of her singing traditional Algerian folk songs.12 This canvas constituted the first pictorial response by an Algerian woman artist to Delacroix’s 1830s depictions of Algerian women. With No to Torture, Niati followed the steps of author Assia Djebar, who in her novel Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1999) denounced Delacroix’s racist and sexist ideology. In her series of canvases, Niati challenged a landmark of Orientalist painting and undermined one of the cornerstones of Orientalism, Delacroix’s painting and its misleading portrayal of Oriental women. In the series, Niati’s women are naked, freed from the veils of Orientalism.

While Niati tears down the veil of the Orientalist fantasy of the harem, she recontextualizes it within the repression and torture suffered by women under the French occupation and the Algerian War. The title No to Torture directly involves the audience in confronting Delacroix’s idealized vision of the harem. In viewing this canvas, and its vanishing female bodies, the spectator is forced to reexamine historical accuracy as well as to question his/her aesthetic experience. As Salah Hassan has described it, “No to Torture demystifies the French idealized [and I would add nostalgic] version of Algeria, which is the absolute reverse of the French abuse, exploitation and genocide of more than a million people.”13

The title No to Torture instantly brings to mind the imprisonment and subordination of the woman/object of pleasure in colonial thought. Niati’s series of paintings progressively erases the facial lines and the body shapes until the spectator is confronted with a fusion of forms and colors, and Delacroix’s clichéd poses become blurry beneath the color. Niati’s deliberate gesture to deconstruct Orientalist representations of women through the progressive erasure of their faces and bodies on the canvas calls into question the identity of Oriental women.

Two decades after Niati, Halida Boughriet’s work also challenges the stereotypical representation of Orientalist bodies by imitating the recumbent poses of odalisques. Practically molded into the pose of an odalisque, the female figures in her series of photographs titled Memories in Forgetfulness (Mémoires dans l’oubli, 2010)14 commemorate women’s history by representing widows who endured violence during the Algerian War of Independence, thereby positing collective memory and silenced history at the center of the photographic medium. In addition, at the entrance to her exhibit, Boughriet displayed colonial propaganda posters used by the French that read “Unveil Yourself” to recall the violence endured by Algerian women who were forced to remove their veils. The female body in her work becomes the site of repressed memory.

More recently, in 2009 Majida Khattari, a French Moroccan artist, challenged notions of public and private space by staging veiled and naked women with her series The Parisians (Les Parisiennes). She plays with the stereotypical codes of veiling and sexualization of Orientalized bodies by displacing the veil’s politicized stereotypes. Niati, Boughriet, and Khattari rewrite history, redirect the gaze on the female body, and challenge Western hegemonies.

The representation or dismantling of Orientalism through the gaze of Middle Eastern artists is situated at the heart of a complex network of histories (colonial/imperialist, diasporic, transnational) and involves multifaceted dynamics of cross-cultural encounters and dialogues: resistance to Western hegemonies, imitations, projections, appropriation, and symbolic imaginings. In the visual arts, the gaze and its powers are the matrix and the transmitters of such contradictory or conflicting subjectivities and ideologies. The questions at stake in this debate are the following: Who is watching whom? How does the projection onto others operate? What happens when constructions of the Other are not only reappropriated and imitated but also reconfigured, reconstructed and reimagined by the gaze?

In Niati’s corpus, the staging of Orientalism sets up unprecedented ways to dismantle Orientalist visual strategies of representation and formulates a resistance in art. It opens up new dialogues on the representation of the body and challenges us to rethink once again the extent to which women artists of the Arab Diasporas re-situate nakedness, the projection of desire and of eroticism in contemporary art.

ZINEB SEDIRA (1963–): NEW RITUALS BEYOND THE VEIL

The act of dismantling male impositions on women’s bodies is taken up by another artist of Algerian descent, Zineb Sedira, who also explores the notions of visibility and invisibility of Oriental female bodies through questioning the Islamic scarf, the hijab. Belonging to the most recent generation of Arab women artists, Sedira was born in Paris and raised by Algerian immigrant parents. She received her art training in the College of Media and Fine Arts in England and she still lives in England today. As she started exploring the different meanings of the veil in her work, Sedira became interested in the ways in which the veil functions in Arab and Western cultures. Her research on the veil has included not only the hijab worn by Muslim women in the East and the West but also what she calls “the veiling of the mind” in several recent interviews. According to Sedira, the “veiling of the mind” is “a complex metaphor for censorship” and a metaphor for the readings or misreading of cross-cultural signs in both Algeria and the West. One of the main questions she raises in her art concerns the differences between the physical veil in Muslim culture and the mental veil in Western culture.

Positioning herself as a cross-cultural artist working in the West, she is acutely aware of the dangers of stereotyping and the risks of reinforcing Orientalist stereotypes when she speaks about Algeria and the veil from her geographical and cultural location. In her works, the female body and the manners in which she covers it and uncovers it become the medium though which power is inscribed and articulated.

In Silent Witness (1995),15 a composition of black and white photographs stitched together, Sedira uses her own eyes as the primary motif so that the focus is placed directly on her as an artist of Algerian descent; the viewer is challenged to confront the female Arab gaze and to reexamine his or her Western assumptions about veiled women. Silent Witness refers directly to the performative acts of looking and of being seen, and the infinite interplay between the gaze, the subject, and the object. The veil, though invisible, is all-pervading in this montage and literally serves to frame the eyes; the female gaze seems to unfold infinitely as if history were repeating itself and as if the female gaze remains forever in the position of witnessing. Moreover, as Tina Sherwell writes, “The use of herself as the subject of her work serves to give identity to the normally anonymous veiled Arab woman.”16

In one of the pieces composing an installation of color photographs titled Don’t Do to Her What You Did to Me (1996), Sedira showcases herself this time in the process of veiling and unveiling. What is interesting to note here is that the prints on the scarf are an assemblage (or patchwork) of photographs of her sister, who appears unveiled in them. The scarf and the photographs of the veiled sister here are therefore nothing but a pretext for artistic creation. In the first frame on the left, Sedira lifts the veil and uncovers her face, yet in the other frames where her head is covered, it is her unveiled sister who appears on the scarf.

Sedira points here to the complexities surrounding any discourse on the veil and the contradictory meanings that the veil can take in either a postcolonial or religious context. In this montage, the act of wearing or of taking off the veil is just an artifice; this gesture points more to the multiplicity of meanings of the veil than to the meaning of the veil itself. As the act of veiling and unveiling is reduced to its performative qualities rather than being prescribed or fixed religious meaning, Sedira challenges the fundamentalist laws that impose the veil on women and replaces those laws with a new diversion, a new pictorial ritual, that of veiling and unveiling. It is no exaggeration to say that Sedira, along with her contemporary Ghada Amer, produces today the most radical and world-shattering art.

GHADA AMER (1963–): AN INTERTWINED LOOK AT WOMEN, SEX, AND RELIGION

Born in Cairo, Ghada Amer was raised and trained in France and currently lives in New York. Her works play with domestic activities which women have practiced and passed on to each other for thousands of years: spinning, sewing, weaving, and embroidery. Like many generations of women before her, Amer sews her sketches into new contexts of visual signifiers, as she plays with the rituals of thread. In the same way as Sedira, she questions the meaning of the veil and the violence surrounding its use and she denounces all stereotypes imposed upon women in both the East and the West.

Executed in continuous Bayeux lace, her Borqua showcases the embroidery of the word “fear” in Arabic in the center (Conservatoire de la dentelle de Bayeux, 1997). It is illustrative of the artist’s interest in challenging the practices and the politics of women’s dress codes in Muslim cultures. In placing women at the heart of her work, Amer engages a dialogue with the folkloric motifs of Mehieddine and her use of repetitive patterns reminiscent of Arabic calligraphy. Walking the same path as Niati and her dismantling of the Orientalist harem, Amer tears down another locus of objectification of women, the pornographic space. She deliberately denounces taboos and religiosity, destroying the cultural icons which obsessively codify the difference between the sexes and establish rules of sexuality in contemporary societies.

If Amer turns to fairy tales, pornographic motifs, and religious texts again and again, it is only to deconstruct them as she invites us to place them in new contexts. The poses that she copies from pornographic magazines and which she reproduces ad infinitum progressively lose their form, and they disintegrate under the threads which she lets hang over the edge of the fabric. The form and poses of the bodies, while recognizable, are in fact in motion, in the direction of Otherness. Here, her art takes form simultaneously from stereotypical motifs (pornographic forms and poses) as well as from the progressive deconstruction of these motifs. Amer’s challenging and bold research on sexuality culminates in her sculpture titled The Encyclopedia of Pleasure, composed of fifty-seven embroidered boxes. The gold thread of the embroidery takes up the text of Abul Hasan ibn Nasr al-Katib’s late tenth-century Encyclopedia of Pleasure and invites us to revisit the appellations of love and sexual practices in Islam, as Sahar Amer has pointed out:

Ghada Amer’s art is not simply a (re)production of pornographic or even erotic images or texts, as critics have suggested. It is rather a reflection on what constitutes sexuality, an invitation for the viewer to think and critique the various definitions and practices of sexuality, to imagine further ways to achieve satisfactory unions, and ultimately an invitation to us all to learn to love in more mature fashions.17

Challenging categories of the feminine and of sexuality while blurring their significance, Amer rethinks them without privileging one over the other. A few fundamental questions constantly recur when considering Amer’s work: How can women be taken out of the conceptual boxes which imprison them, both in the East and in the West? How can we denounce societal constraints on the female body for what they are? According to the laws of Amer’s pictorial universe (and following in the footsteps of Mehieddine), the first step is to make women visible and to free them from the stereotypical representations sensationalized by the media as well as from the exploitation of their fetishized bodies, particularly in pornography. In other words, Amer “unveils” women, so to speak, liberating them from the domestic enclosures to which they have so long been relegated.

Through ironic imitation, reproduction, and derivation of pornographic and religious texts and models, Amer slowly deconstructs clichés associated with women’s sexuality, and creates a new feminine body cartography which is one of her key strategies. In her Private Room (1998, figure 6) she embroiders the words associated with women and love in the Qur’an. Moving away from the 1960s notions and ideologies of the European women’s liberation movement, which often implied little more than liberating women of their clothes in order to reveal their bodies and make them visible, Amer is concerned with undermining societal controls in order to free women from the veils that hide their identity. Her intercultural investigation denounces the multiple mechanisms of repression of women on a global scale.

Their provocative poses and their mocking glances decry all such labels as “erotic,” “sexual,” “pornographic,” “feminist,” “abstract,” and “figurative.” All suggestions of corporality slip away into some space between color and cloth, between painting and sewing, in this “choreographic writing,” where forms fall away from colored threads and paint, juxtaposed, or intermingled until a new stitch accentuates their different textures at the height of Amer’s painterly embroidery (figure 7).

Yet the story of daily life that Amer tells us begins simply, like in a fairy tale. The four works of the 1991 series titled Five Women at Work already reveal the essential aspects and the acuity of her vision. Women were busy with domestic work: cooking and ironing, for example (La femme qui repasse [The woman who irons], 1992). They have left their beauty secrets embroidered on kitchen rags (Conseils de beauté du mois d’août: Votre corps, vos cheveux [Beauty tips for the month of August: Your body, your hair], 1993). So, these activities traditionally associated with women’s domestic roles are brought into the public realm of art, as Amer blurs distinctions between private and public space. It matters little in Amer’s universe whether women are represented in the act of performing housework, or if they are prisoners of Western harems. These two modes of representation of women fall back upon one issue: women’s subordination and fantasies by European voyeurs and consumers throughout history.

From this perspective, one can say that women artists coming out of the Arab traditions forge, each in her own way, a new space of resistance for women while finding for themselves a place within the artistic tradition. Whether the childhood environment that Mehieddine represented in her paintings, or Niati’s destruction of Delacroix’s phantasmal harem, Sedira’s radical questioning of the imposition of the veil upon women, or Amer’s progressive deconstruction of the pornographic universe, there is no doubt that these artists plunge into the deepest recesses of their cultures and their cultural/religious heritage, inviting us to rethink the status of women’s bodies and the radical representation of women situated in opposition to fundamentalist ideologies. Moreover, Amer’s rewriting of the Qur’an and of lost texts such as L’Encyclopédie du plaisir calls for a rereading of many texts from a new feminist perspective—a radical and courageous proposition in this era of contemporary fundamentalisms.

THE NEW EGYPTIAN AVANT-GARDE WITH NADINE HAMMAM

Nadine Hamman is a member of the most recent generation of women artists challenging the conventional views of Arab women in the world of art. Born in 1973 in Cairo, Hammam lives and works today in London. A multidisciplinary and conceptual artist, she works with painting, writing, and sound installations. She deconstructs gender dynamics and social taboos by investigating the relationship between the public versus the private.

Hammam’s artistic journey speaks both to the persistence of art to manifest itself in times of revolution, and to the new ways in which the current Egyptian artistic avant-garde is coming to the forefront. Her work also defies stereotypes, confronting and challenging constructions of the feminine in today’s world. This is a particularly pressing matter as many women’s organizations address the regression of the status of women in Egypt today. And this is precisely why Hammam’s timely work demands our attention.

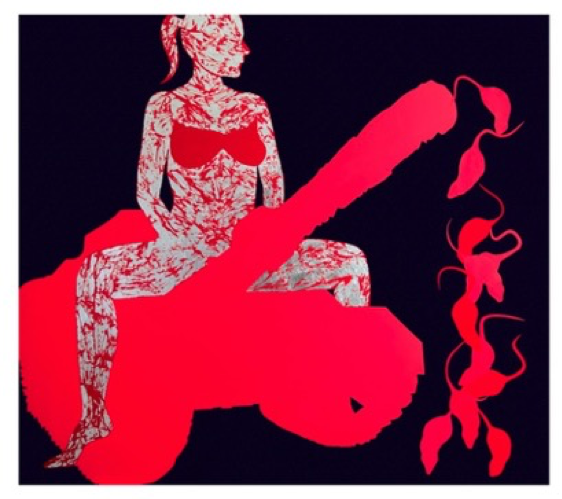

Moreover, in the heart of the highly mediatized Egyptian revolutions, Hammam’s artistic inquiry engages us in new ways of thinking about the intellectual and artistic consequences of revolutions and the experiences of historical and ideological unrest. Her art undoubtedly demonstrates and confirms that women artists from the Arab diasporas are actively engaged with their times. Her canvas Tank Girl (2012, figure 8) is a direct reference and her response to the “Blue Bra Girl,” the young woman who was dragged violently by the Egyptian police during the 2011 uprising. In a recent interview Hammam explains the message she intends to convey with her Tank Girl whom she considers one of her most powerful female figures:

Tank Girl is a reference to the “Blue Bra Girl,” and every other woman who was assaulted and violated during the uprising. She is an icon for every woman. She is also Egypt in the feminine (in Arabic). This work is a pun on the word “tirkab,” Arabic for “to ride,” which also connotes various other meanings, to overcome, to be ridden―to have power over the other. She is strong, proud and defiant, the inverse of a power dynamic between the army regime and the people as well as men and women.18

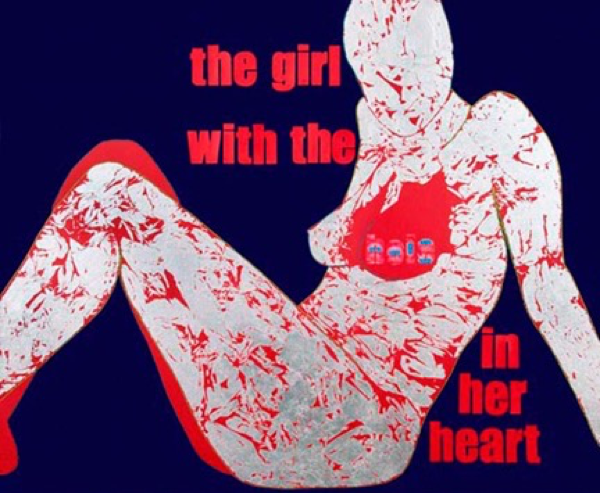

At first glance, Hammam’s creations, Tank Girl and The Girl with a Hole in Her Heart (2013, figure 9) are singularized by the color red and bear a highly charged symbolic power heightened by the experimentation with textures and mixed media. Her female figures are daunting and forcefully occupy the entirety of her pictorial space. In her composition The Girl with a Hole in Her Heart, the female body becomes the memorial for memory and trauma, as we noted earlier with regard to Halida Boughriet’s work.

The female figures and the words printed on Hamman’s female bodies are intense and openly deploy nudity, a domain that has traditionally been the prerogative of men. With Amer and Hammam, female figures can no longer be reduced to decorative and sexualized models; these artists break taboos, giving center stage to love and desire, or the lack thereof. The representation of female bodies cries out the needs of women on a global scale and calls for our direct participation.

With her recent work titled WHY, Hammam pursues in her art the dynamic process of mirroring and viewing oneself. The words taken from the traditional repertory of love (“Love,” “Kiss,” “Forever,” etc.) on the canvas assembled from broken mirror pieces are both reflecting and fragmenting the self and she invites the viewer to engage in the work as his or her own image reflects back from the written words. It is also important to note that no letters are the same because each is assembled with different pieces of broken mirror. With Hammam, the mirroring effects of words and the questioning of language through reflected subjectivities puts the viewer in an explicitly unequivocal and unstable position. The viewer can no longer identify with the traditionally assigned meaning of language and this is how Hammam’s artwork challenges fixed meaning, fixed beliefs and ideologies, and histories in the current Egyptian historical context. This new turn on how art may engage the viewers with the writing of history takes a decisive stand against all popularized and mediatized renditions of the Arab Spring by male politicians and journalists. With Hammam, the viewer has to take action and responsibility for the words in which he/she is reflected. This is precisely where the political strategy of Hammam’s art is at work. Her art is purely illusory since the words emerging from the broken and missing pieces can never be fully recomposed. On the contrary, the seven works that compose the series WHY reveal a conceptual strategy at work that hands us only the mere illusion that meaning and past histories can be fully reconfigured as we walk close to and away from the compositions. This type of artistic experience is participatory and this original artistic gesture takes on a crucial relevance in today’s Egyptian society that is trying to redefine itself.

Following in the footsteps of generations of Arab feminists and of their Western counterparts like the Guerilla Girls in the 1980s, Amer and Hammam’s work claims the right to represent the female body from the Arab world. Their message of love and images of women invoke history, open new body cartographies, and new imaginings of the female on a global scale. They both invite us to rethink the ideologies of the Arab Spring in our fast-globalizing and mediatized world. Above all, they subvert the image of women in the media and create a new space of dialogue for women and about women.

In conclusion, Arab artists deliberately question representations of gender and reinsert nudity into the center of representation, drawing inspiration from a rich past over the course of which nakedness was central to representation, as was the case with the Umayyad frescos from the Transjordanian desert of the eighth century, and from Tabriz in the sixteenth century, with their numerous erotic scenes. These contemporary artists reclaim and reconnect with a past that has been erased and silenced for centuries. They are defiant and succeed over adversity in today’s art world, all the while reclaiming women’s history, each with her individual style and heritage. Paradoxically, it is in response to Orientalism, through the parodic and often exaggerated staging of Orientalism, and its phantasmagorical projections of the Orient that contemporary artists have rediscovered and resituated the body (and nakedness) in contemporary Arab visual cultures. This is also the case of the Moroccan Medhi Georges Lahlou and his male belly dancers, who mimic Hollywood clichés yet open new perspectives on performance of gender in the context of belly dancing. Although many artists have drawn inspiration from Orientalism, as I have pointed out, they have simultaneously distinguished themselves from these tenets not only to question and transcend the hegemony of Western modernity, but also to create a new original artistic style.

It is in the liminal space between the legacies of Orientalism and the particularities of their individual historical contexts, the restaging of these legacies, and the emergence of these artists on the international/global artistic scene that Arab artistic expressions are making themselves heard today. Their artistic research facilitates and brings to life new dialogues between East and West and above all frees such dialogues from the constraints or preconceived notions of the East or of the West. This liminal space and unique positioning of the artists thus creates a highly fruitful locus, permitting them to look both from within and outside of their cultures, allowing them to occupy and to gain international recognition in the field of contemporary artistic creation in an original way, all the while transmitting or rewriting their own cultural heritage.

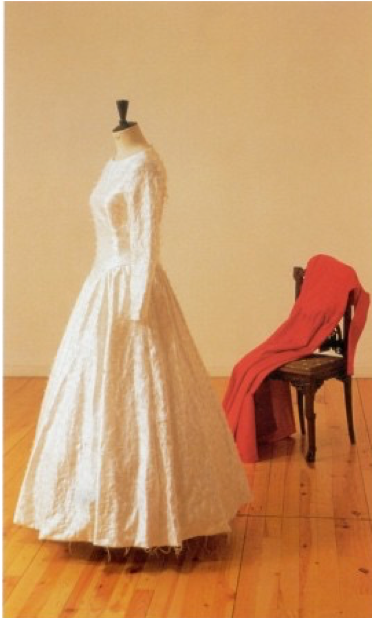

Most importantly, the artists considered in this study are pioneering a new field or genre of artistic expression in the Arab diasporas; they have literally paved the way for generations to come. From this standpoint, it comes as no surprise to find two decades later the echoes of Amer’s installation The Sleeping Beauty (La belle au bois dormant, 1995, figure 10), consisting of the embroidery of the fairy tale on a look-alike wedding dress in the artistic production of today’s newest generation of artists in Australia.

In the same way that Amer challenged the mythology of fairy tales and the symbolism of the white wedding dress, Zeina Iaali exposes19 to the viewer her own wedding experiences and deliberately aims to “peel back her cultural layers.” Two decades after Amer, in her 2012 installation Made to Measure (figure 11), Iaali explains and puts on trial the marriage expectations placed on “the good Muslim girl”:

I was looking at the idea of the second lounge room that I grew up with. The room that was only there for show and to be looked at but never to be enjoyed or used. I used this to compare it to my experience of growing up as an Arab woman and all the cultural and socialized nuances that came with that. I was overprotected growing up. To the point where I wasn’t allowed to go out anywhere with friends or be un-chaperoned. I went straight from my father’s house to my husband’s house when I got married at twenty-two and again felt like I had to keep up appearances and be “the good Muslim girl.”20 The plastic chair is the protective casing and can be displayed on top of the chair or separate and facing it. I am interested in peeling back my cultural layers.21

Attempting to challenge the expectations placed on “the good Muslim girl” in this current political context characterized by a return to a conservative agenda in the Middle East and beyond, transforms “good girl” into a “bad girl.” Henceforth, when used in this context, the term becomes synonymous with “defiant girl” or “disobedient girl” and bears no moral overtones. “Bad girls” are defiant women who challenge the norms, who take it upon themselves to rewrite history, and who are not afraid to challenge male authority, even when faced with strong opposition. Unlike the Ukrainian group Femen, which has made the international news, and which is organized and manipulated by a male mastermind, today’s “bad girls” of the Arab diasporas rely on themselves. Their voices and visual messages are present through social media, the press, in academic institutions, and in art exhibits around the world. Yet, as they play out multiple roles in the world of art, they also occupy contradictory positions in the global media scene. On the one hand, Western audiences, funders, and marketing schemes easily target them. Yet, on the other hand, the visibility that the media provides to “bad Arab girls” undoubtedly opens up new communication possibilities made available in this information age and simultaneously creates an unprecedented and important forum for women’s resistance, activism, and body talks.

NOTES

Marie-Jo Bonnet, Les femmes dans l’art (Paris: Gallimard, 2004), 148. My translation.↩︎

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. I: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Random House, 1978). According to Foucault, the “cycle of prohibition” is interconnected with sex and power: “To deal with sex, power employs nothing more than a law of prohibition of sex. Renounce yourself or suffer the penalty of being suppressed; do not appear if you do not want to disappear” (84).↩︎

See Said.↩︎

Although I will be focusing on the visual art in this essay, I would like to point out that the hip hop scene is also a fertile space of artistic creation for women of the Arab diasporas. Malikah Fattouh, the Lebanese-Algerian “queen of Arab hip hop,” may serve as one example of how women play an important role in the world of music and resist cultural domination both from the East and the West. Fattouh’s lyrics reveal her critical stance on patriarchal Islamic cultures and her music aims to give agency to women. She is among a new generation of young female activists on the front lines who battle publicly through music and who provide alternative views that openly challenge Western stereotypes of Arab women propagated by the media.↩︎

The work of all artists presented in this study is easily accessible on Google Images.↩︎

Audre Lorde, Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power (New York: Out and About Books, 1978).↩︎

Salah M. Hassan, ed., Gendered Visions: The Art of Contemporary Africana Women Artists (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1997), 3.↩︎

Australian art critic Oliver Watts confirms this point of view: “Australia is in a very good position to engage with a politics that is outside the Euro-American axis. There is a strong interest as part of the diversity of contemporary art to engage Arabic and Muslim artists from around the world and at home. We have a good opportunity and responsibility to create connections to the rising contemporary art scene in Indonesia and that work is happening currently. Khaled Sabsabi was shown in the recent Biennale of Sydney. The work of the brothers Abdul Abdullah and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah have also been shown in the ATP and the Adelaide Biennale respectively. But there are many others.” Personal interview, October 2016.↩︎

Personal interview, September 2016.↩︎

Frank Maubert, ed., Baya (Paris: Galerie Maeght, 1998).↩︎

Abdelkébir Khatibi, L’art contemporain arabe (Paris: Institut du Monde Arabe, Editions Al Manar, 2001), 80.↩︎

Salwa Mikdadi Nashashibi, Etel Adnam and Laura Nader, eds., Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World (Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1994), 58–62.↩︎

Salah M. Hassan, Gendered Visions, 13.↩︎

The series Memories in Forgetfulness is available at the following link: http://www.halidaboughriet.com/2010/08/une-memoire-dans-loubli/.↩︎

The canvases discussed here are reproduced in Contemporary Arab Women’s Art: Dialogues of the Present, ed. Fran Lloyd (London: I.B.Tauris, 2002), 67–68.↩︎

Tina Sherwell, “Bodies in Representation: Contemporary Arab Women Artists,” in Contemporary Arab Women’s Art, 67.↩︎

Sahar Amer and Olu Oguibe, Ghada Amer (Amsterdam: De Appel, 2002), 14.↩︎

This interview was conducted in November 2013.↩︎

This installation was part of the first exhibit devoted to Arab women in Australia in 2012. The exhibit, “No Added Sugar: Engagement and Self-Determination; Australian Muslim Women Artists,” took place at the Casual Powerhouse Arts Center, May–July 2012. Iaali was the only artist to confront the body and sexuality in her works.↩︎

My quotation marks.↩︎

Personal interview, September 2016.↩︎