Florence Martin

NEW MAGHREBI DIASPORIC FILM WITH AN AMAZIGH TWIST: BENAMRAOUI’S ADIOS CARMEN (2013)

Over the past fifteen years or so, the cinema of the Maghrebi diaspora in Europe has evolved drastically under the fresh impulse of its new directors, in directions most visible in narrative foci, ways of filming, and new imaginative funding schemes.

In order to trace how the most recent diasporic films depart from their predecessors, I follow one of the Ariadne’s threads of this body of work, the emigration/immigration films, and tease out their innovative perspectives and narrative structures, foci, and angles. One of the most brilliant recent exemplars of such cinema is Mohamed Amin Benamraoui’s critically acclaimed first feature film, Adios Carmen (2013). The impressive list of awards1 it garnered across the world begs the question: What about this diasporic film has prompted such recognition transnationally when (a) it is not in Arabic (let alone French or English!) but in Tamazight (to be precise, in Tarifit, the variant of the indigenous language spoken in the Rif region), (b) it refers to the particular history of two displaced communities (the Spanish one in Northern Morocco and the Rifan one in Belgium) against the backdrop of Hassan II’s nationalism in the 1970s? This very private visual narrative is a political film on emigration that looks at the underside of classic travel narratives by focusing on the ones who are left behind, not those who are emigrating. In that, Mohamed Amin Benamraoui flips the script of the usual narratives of emigration and offers a fresh vision of Amazigh transnational cinema (rather than Moroccan cinema). Yet this is only the most visible first of several reversals: in his abundant reference to the popular Hindi cinema of the time, he turns the film into a hybrid montage of visual cues that link Adios Carmen to a world cinema squarely from the Global South, thus opening up a new interpretation of cinéma-monde that sheds light on the new Maghrebi diasporic cinema with an Amazigh twist, away from European or Hollywood centers.

NEW DIASPORIC DIRECTOR MOHAMED AMIN BENAMRAOUI

NEW DIASPORIC CINEMA

Coming after their forefathers’ “beur cinema,” the recent cinema of the Maghrebi diaspora has been described by critics, inter alia, as “postcolonial immigrant,” “post-beur,” “accented,” or “transnational” in attempts to pinpoint the varying degree of cultural hybridity of its production.2 Furthermore, in academic circles, it has often been subsumed under the ill-fitting umbrella of “francophone cinema”3 ―although it is not always in French―and, more recently, has been analyzed as part of cinéma-monde.4

The numerous moves from one label to the next testify to the difficulty of conceptualizing the ever-elusive genre: a Maghrebi diasporic cinema that can no longer subscribe to a center/periphery model but to a transnational, cinéma-monde, collaborative model, de-orbited from its previous poles of attraction (France or Belgium, for instance). The phrase cinéma-monde was coined to express two distinct phenomena: first, a global cinema production subjected to Hollywood’s hegemony;5 second, an ill-fitting adaptation of the literary criticism of littérature-monde to a francophone context.6 Although the argument for cinéma-monde as a possible descriptor applies to what academics used to call “francophone film,” the latter comprises the production of directors from France’s former colonies, including from the Maghrebi nations. If, by cinéma-monde, one means a hybridization of West and East―or, in our case, North (Europe) and South (Maghreb)―then, indeed, the new diaspora’s production is part and parcel of cinéma-monde in its funding, its foci, its narratives, and its way of reorienting the gaze of the viewer onto the hybridized situation of the diasporic subject. The funding follows the same circuitous route as Maghrebi film does:

We are no longer dealing with postcolonial films transnationally made and/or funded with France as the main pull, but rather with a reconfiguration of transnational teams that calls for a local/translocal/ transnational collaboration of people, and movements of ideas and languages that are de-centered, de-orbited, free.7

Taking Adios Carmen as an exemplar, the financial montage of Benamraoui’s film casts light on the alternative funding sources now available to Arab and diasporic directors. After he received aid in Morocco from the Centre du Cinéma Marocain (CCM) in Rabat, Belgian producer Geneviève De Bauw (Thank You and Good Night Productions) became interested in the project. The shooting started, but money was anticipated to be more than tight at the post-production stage. Belgian editor France Duez then suggested creating a thirty-to-forty-minute-long ours (pre-montage of the filmed material), and using it to apply for funds at international festivals and other venues. Benamraoui took it with him to Dubai and applied for and received financial support from Enjaaz as well as help from the Global Film Initiative in the United States (currently the American distributor of Adios Carmen). The entire production structure was done in real partnerships with individuals as well as with various groups internationally: in Belgium, for instance, sound engineer and mixer Alek Goosse ended up coproducing as well. As a result, the production is multinational (Moroccan, Belgian, and Emirati) and the film a work of true, equitable collaboration across multiple borders.

The same dynamic freedom presided over the choice of treatment of the topic of Adios Carmen. Benamraoui had chosen to tell a story of emigration but not from the usual angle and not with the usual linguistic and cinematic references. As a result, in contrast to other cinematic narratives by Maghrebi filmmakers operating from Europe, Adios Carmen does not actually offer the story of a diasporic subject crossing borders, reckoning with exile, and surviving in an alien culture. It does not follow attempts to leave either Morocco (e.g., What a Wonderful World, Faouzi Bensaïdi, 2006) or Algeria (e.g., Harragas, Merzak Allouache, 2009). It does not promote the clear feminist agenda of the first wave of diasporic Maghrebi female directors, by providing a recently immigrated woman with some degree of agency in household decisions (e.g., Inch’Allah dimanche, Yamina Benguigui, 2001) or a female counter-history to the male history of the Algerian war of liberation (e.g., Sous les pieds des femmes, Rachida Krim, 1997). Neither does it describe the generation gap between immigrant parents and their children (e.g., La graine et le mulet, Abdellatif Kechiche, 2007), nor does it reside in the suburban ghettoes of Paris (Wesh wesh, qu’est-ce qui se passe?, Rabah Ameur-Zaïmeche, 2001) or Brussels (Black, Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah, 2015). It also does not tell the tale of a return to the country of origin as Française (Souad El Bouhati, 2008) or Tenja (Hassan Legzouli, 2004) did. Neither does it show a binational, bisexual protagonist crossing back and forth between the old and the new country as in Bedwin Hacker (Nadia El Fani, 2003). And yet it is a diasporic film that belongs to the same ensemble as these very diverse “accented” films, as understood by Naficy: “The accented filmmakers’ films . . . form a highly diverse corpus, as many of them are transnationally funded and are multilingual and intercultural.”8 What perhaps distinguishes Benamraoui’s work most acutely from his colleagues’ is the uniquely “glocal” niche in which he inscribes his film. In that, he might be one of the most “accented” of them all, for

unlike most film movements and styles of the past, the accented cinema is not monolithic, cohesive, centralized, or hierarchized. Rather, it is simultaneously global and local, and it exists in chaotic semiautonomous pockets in symbiosis with the dominant and other alternative cinemas.9

He zooms in on the local, placing his film squarely in a small town, Nador, in the Rif. And yet, to the intense local flavor of the filmic narrative and language he adds a global dimension: that of quoted films from another “alternative” cinema, the 1970s Indian films popular in Moroccan picture houses at the time. Here, the third twist is that the intertextual or interfilmic design of Adios caters to a nostalgia felt by his first-row audience, the Moroccan/Rifan diaspora in European urban centers, and runs contrary to a European audience’s expectations of dominant cinematic references. With that move, the director subverts the unquestioned hierarchy of cinema in world cinema: Indian cinema becomes displaced from its “alternative” status to become the central reference point (Bollywood is, after all, the dominant cinema in the world in terms of production). Its constant interplay with Bollywood inscribes Adios in a welt kino, a world cinema whose points of anchor are sometimes at odds with the previous diasporic films, with a singular take on the Maghrebi diasporic subject. Francophone cinema is not referenced at all in this Amazigh, semi-autobiographical film: Benamraoui here pushes the envelope of the new Maghrebi diasporic cinema, with an―Amazing!―Amazigh twist or two.

BENAMRAOUI AS DIASPORIC SUBJECT FROM THE RIF

Mohamed Amin Benamraoui has forged his own very distinct path to come to cinema between his native Rif (in northern Morocco) and Belgium where he has resided since the mid-1980s. He is bicultural: he was raised in Tarifit (the Rifan version of Tamazight), in large part by his grandmother who introduced him to legends and tales of the Rif, before he received his college education in French and Flemish (he has a master’s degree in sociology from the Catholic University of Leuwen). Once in Brussels, he decided to study film and, shunning a classic curriculum at an established school, opted for a small structure (L’Académie des Arts de Molenbeek) where he studied under Belgian filmmaker Thierry Zeno from 1994 to 1998, and took photography classes at the Académie des Beaux Arts in Brussels.

Unlike first generation Maghrebi immigrants in Europe who tended to keep as silent as possible about their original culture, Benamraoui has always proudly celebrated his heritage in the host country. Based in Molenbeek, he became a cultural activist and organized various Amazigh cultural festivals that brought together the immigrant population from the Rif who had emigrated en masse to Belgium and France during the reign of Hassan II in Morocco.

The latter therefore constitute not simply a Moroccan diaspora in Western Europe, but a Rifan diaspora that speaks Tarifit and shares a specific history and culture with complex identity politics at stake: not only are we talking about a displaced population for economic and political reasons, residing outside the land of their ancestors, but also about an indigenous population pushed out by the Arab makhzen (the Moroccan monarchical system of power) that still does not officially recognize their identity as distinct. Although the purpose of this paper is not to trace the history of the Imazighen in Morocco10 (roughly 50 percent of the total population), let’s briefly sketch the Amazigh Moroccan situation as it relates to the Rif region. There are three main Amazigh groups (each containing a high number of distinct tribes) that speak three different dialects: Tarifit in the Rif mountains, Tamazight in the larger region of the Middle Atlas, and Tashelhit in the Anti-Atlas and plains. Hence the “Tamazight” (the generic name for the indigenous language) that is spoken in Benamraoui’s film is actually Tarifit.

The Imazighen (i.e., “free men”) of the Rif region historically known for their resistance to invaders (the Rif actually seceded once from the Moroccan kingdom as it won against the Spanish colonizer under the leadership of Abd el-Krim who created the Rif Republic, with its own government and currency from 1921 to 1927) demonstrated en masse in 1958, two years after independence.11 They sent a petition outlining a list of complaints to then King Mohamed V in which they remonstrated against their marginalized status in the Kingdom of Morocco and asked to be fully liberated from Spanish occupation in their region. At that time Prince Moulay Hassan was at the head of the royal army forces. In reprisal for the audacity of the Rifan delegation’s demands, the future Hassan II ordered massive repression in the Rif, aided by the (in)famous Mohamed Oufkir, whose orders were so violent and cruel that they earned him the sinister nickname Butcher of the Rif: at least eight thousand Rifans were killed, and more, including women and children, were beaten and tortured. Over the next four decades, the makhzen cut off the Rif economically from the rest of the kingdom. This relentless mistreatment of an entire region triggered massive emigration to France, Belgium, and Germany. Other demonstrations were ruthlessly repressed over the years, most notably those in 1965 and 1984 that went down in Rifan memory as horrific massacres.

One of the most salient differences between Moroccan history and Amazigh history highlights the fact that the Imazighen―the original indigenous population―have, unlike the Moroccan Arabs, been subjected to two layers of colonialism instead of one: an Arab one in the seventh century, and a European one in the twentieth century (a French protectorate in most of the Kingdom from 1912 to 1956; and a Spanish one declared in 1912 along the Mediterranean in the north and in the southern portion of the territory). With the first came Arabic and Islam; and with the second came French and Spanish as the languages of the oppressors. Fast-forward to the independence of Morocco in 1956: Mohamed V returned from the exile to which the French had condemned him in Madagascar. As king, he was (a) an Arab, and (b) the leader of the believers (he belongs to the dynasty of the Alawites, i.e., he is a descendant of Ali, the Prophet’s son-in-law). He created alliances with powerful families across the kingdom and ruled via a system of intrigues and councils that form the cornerstone of the makhzen system. Since independence, three kings have reigned over Morocco via that system and done very little for the Imazighen. To wit: to this day, Arab and French are the official languages, for instance, and if Hassan II allowed Tamazight to be taught in a few schools in 1994, if Mohamed VI declared Tifinagh its official alphabet in 2003, the Imazighen still had to wait till 2011 for the makhzen to recognize Tamazight as an official language (and that, only at the eleventh hour in an attempt to avoid a Moroccan Arab spring).

Hence, the “free men” of the Rif in and around Molenbeek were Benamraoui’s audience at the cultural events he organized, like the Amazigh film festival (Urar Imazighen) at the Nova Cinema in 2000. He further was looking to expand his audience and worked on various cultural programs for the RTBF channel.12 In his work, Benamraoui, while part of the Moroccan diaspora in Belgium, has always clearly identified first and foremost as “un Rifain” and it is a Rifain diasporic audience that he seems to be addressing in their language both in the events he stages and in his film. As a cultural activist, his use of Tarifit has a profound political significance.

Berber and Darija translate the culture of the people whereas classical Arabic, French and Islam represent the culture of the learned. In this multicultural and multilingual context, the legitimacy of the state is largely based on a written culture that is very tightly connected to power.13

Yet, in Benamraoui’s life and creations, the political is never far from the personal. When asked about the use of Tarifit in Adios Carmen, he underscored what a deeply personal mode of expression and how empowering his mother tongue was: “I realize that there are very powerful elements in Tamazight, my native language, at least for me. That’s where I can find universal emotions, things that belong to all of us, but in my language.”14 Aiming for a universal message, he nonetheless verbalizes it in a local language, so as to be as close as possible to the authentic translation of emotions.

In another reversal from the usual practices in film, he also decided to plant his camera squarely on the side of women and children in Adios Carmen rather than on the men. In that, and in his use of Tarifit, he sides with the oppressed against the abuse of both the central power and the power of males in the immigrant population. Hence, the first twist in his first feature fiction is that he does not draw attention to the plight of male immigrants. Rather, he focuses on how and why women emigrate from Morocco and on what happens to the children left behind, in other words, on the most vulnerable people in the story of migrations, those who have no say over the decisions made about their lives.

Particularly in patriarchal societies, of which Morocco is one, women lack an equal stake in migration decision-making, while children are almost inevitably in a weaker position vis-à-vis their parents. Hence, it is likely that women and children have generally less agency with regard to migratory behavior. This pertains not only to migration by fathers and male spouses, but also to women's and children’s own migration: they can either be put under considerable pressure to migrate (alone or in the context of family migration) or be excluded from access to mobility against their will.15

As a diasporic filmmaker, Benamraoui chooses therefore to zoom in on the voiceless, often forgotten subjects of emigration who are also diasporic subjects en souffrance, that is, caught in an untenable situation, stuck in a motionless, aching time and space of waiting: the silent mother forced to follow her new husband abroad, pining for her son at home, and the son at home, awaiting his mother’s hypothetical return. Looking thus into the drama of Rifan population’s displacement, Benamraoui goes back to shoot his film in the Rif in order to offer an intimate, empathetic look into the unique perspective of a child left behind by his powerless mother.

He is not the first diasporic Maghrebi director to have broached both the topic of women and children left in Morocco and the filmic references to “alternative cinemas.” He aligns here with two women directors from the new diaspora: Tunisian diasporic Raja Amari whose films (Satin Rouge, 2002, and Secrets, 2009), under the influence of the Egyptian golden age of cinema and its musicals, constitute veritable homages to the dance and music of these films; and fellow Moroccan and Amazigh director Yasmine Kassari who was the first one to tell stories of the women left behind in Morocco by their husbands who emigrate to Europe, in L’Enfant endormi/The Sleeping Child (2004). It is rare to see a diasporic director choosing to follow in the footsteps of several alternative female diasporic directors to narrate a story of emigration and its traumatic side effects on an orphaned child.

SHOOTING FROM BELOW: AMAR’S PERSPECTIVE

SYNOPSIS

Although shot in Assilah, the filmic narrative is precisely located in Zghanghan, a town in the Moroccan Rif region, not far from the Spanish enclave of Mellila, in the summer of 1975. The population is mixed: Spanish refugees from Franco’s regime and native Rifans. 1975 is the year when Franco lay dying in Madrid. The imminent demise of the Franquist regime in Spain has deep repercussions in Morocco, and is linked, in particular, to Hassan II’s campaign of the “Green March.”16

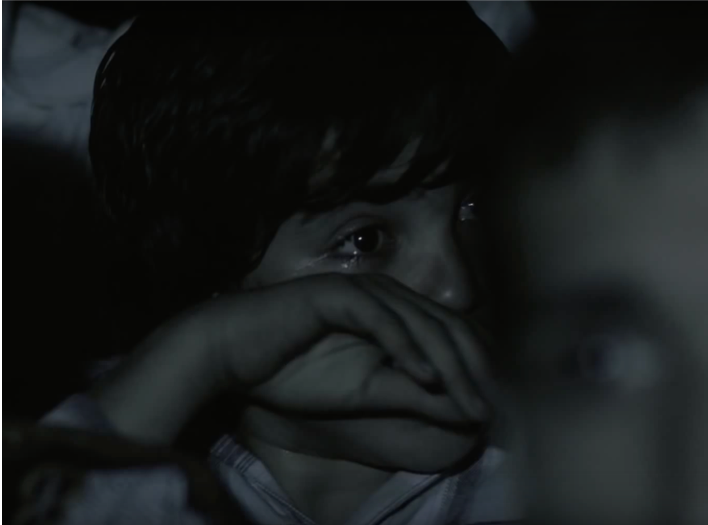

Zahia, a widow, and her ten-year-old son Amar live with her brother, Hamid. Abderrahman, a previously married suitor, asks her to marry him and follow him to Belgium where he has emigrated, but without Amar. The little boy is left to live in Nador with Hamid, a violent drunk who survives on contraband and petty crime.

Amar, a sensitive child who does not know how to fight, grows more and more solitary. When Carmen, a Spanish neighbor, invites him to the Rif Theater where she sells tickets and where her brother Juan is the projectionist, he discovers the world of cinema. Although they do not speak each other’s languages, Carmen and Amar become fast friends. When Amar receives a tape from his mother, it is Carmen who plays it for him on her tape player, thus further illustrating the surrogate-mother role she takes on in Zahia’s absence.

Amar now spends his days thanks to her at the movies and finally makes a friend his own age: Saïd, the boy who looks after the movie-goers’ bicycles while the film is playing. After each screening, Amar tells him the story of the Hindi film that he has just watched. Nador is a violent place for children (and women). Saïd saves Amar from a violent sexual predator.

Meanwhile, tensions escalate between Spain and Morocco―as we hear on the radio and see on the newsreels at the Rif. Hassan II’s nationalist campaign against the Iberian colonizer intensifies. Spanish settlers are being harassed (Juan by Hamid, in particular) and Carmen and her brother eventually decide to move back to Spain. Amar is abandoned by a mother figure a second time. He is so distraught that he refuses to go and bid her farewell.

Meanwhile, Hamid is arrested for his vicious attack on Juan and ends up in jail. Amar’s life improves, and Saïd teaches him how to fight Latif, the violent kid next door who has been bullying him all along.

Although the filmic tale is replete with the tropes of a traditional coming of age story―Amar learns to fight for himself, he will grow up to be strong, he learns everything about cinema, and so forth―the way it is shot signals different stories of resilience around the central figure of Amar, the little boy in 1970s Rif.

Amar is the undesirable surplus of emigration: he is an economic burden as he is not productive yet and must be fed by adults. His uncle views him as an economic encumbrance (even if Zahia sends him money from Belgium every month to feed her son. Hamid, who is a pathetic small-time crook, uses his sister’s money to sustain his nightly drinking habit in the nearby Spanish bar) as do the neighbors (starved by his uncle, Amar is reduced to begging for some bread from them). After his mother, whose status as widow made her vulnerable both economically (she can only find low-paying jobs cleaning houses) and socially (to the malevolent gossip of women in the neighborhood who see a widow as a potential sexual threat), he is the next―and ultimate―victim of Rifan emigration, that is, of Hassan II’s policy of starving the Rif region of all possible resources.

Amar also lives in a region in which settlers from Spain reside and speak a different language that he does not understand. He is, literally, pushed to the margins of his own native land, economically, politically, linguistically, and one might even think, existentially. In that, he stands as a metonymical representation of the fate of the Imazighen in the Rif, whose language is not Arabic, whose native land has been colonized three times―by the Arabs, the French, and the Spanish―and who are systematically isolated from the central power and riches of the Arabic-speaking makhzen. Via the image of the child (about to embark on his journey to self-discovery) and of his initiation into cinema, the filmic narrative weaves in complex identity politics. Amar is the next generation of Imazighen forced to emigrate: although at home, he is never allowed to be at home fully.

Shot from the perspective of the child, “home” is an unstable notion. It is, in Freudian terms, unheimlich: what is familiar in his immediate surroundings shifts in several ways. What was familiar becomes alien and dangerous (such as the unpredictable intrusion of terrifying male danger under the traits of his uncle, of aggressive pedophile Bount, of the neighborhood bullies); and what was alien becomes familiar and comforting (Carmen the foreigner becomes motherly; Spanish becomes a little more understandable). Just as in any coming-of-age story, characters in the film shift positions as Amar grows up: Moussa the bicycle-shop owner, for instance, although he braves social interdictions, ends up a coward. And, of course, Amar, after his initiation into the world of teenage boys, also changes, learns to defend himself and shows treasures of resilience.

LITERALLY SHOOTING FROM BELOW

Let’s take a look at the opening sequence. The first two minutes offer a parallel montage of two scenes: an exterior one focusing on Amar, the protagonist, and an interior one centering on men discussing Zahia’s fate in Hamid’s living room while Zahia is listening in on the discussion from the hall. The film opens with the exterior one, shot at ground level (a visual echo of the Moroccan short, Faux pas/False Step, by Lahcen Zinoun17): we see the lower part of two pant-covered legs (from the shoes up to just below the knee) walking on the grass, then a child’s hand rummaging through the grass. The camera zooms out to reveal the young boy picking up strips of discarded film. The camera thus focuses on both film turned to refuse and the protagonist in the exposition scene, establishing a powerful visual metonymic relationship between them. The insistence on film that has been trashed takes on some of the values associated with the “garbage” Robert Stam described in his famous essay on Brazilian trash cinema:

Polysemic and multivocal, garbage can be seen literally (garbage is a source of food for poor people, garbage as the site of ecological disaster), but it can also be read symptomatically, as a metaphoric figure for social indictment (poor people treated like garbage, garbage as the “dumping” of pharmaceutical products or of “canned” TV programs, slums―and jails―as human garbage dumps).18

The metaphoric value of Amar as dumped human garbage lies in his status as forgotten victim of the grand récit of emigration to better one’s social status. Not only does he not fit in the emigration narrative of the newly minted couple about to get a new beginning away from Nador, he is an impediment, an émigré’s burden to be unloaded before departure to a new horizon. Hence, we first meet Amar while his fate is being decided upon, in his absence, by patriarchal figures: his uncle and his mother’s fiancé. While Amar forages for film trash in the weeds, he is literally being “dumped” by the adults in the house. The fitting low angles of the opening scene visually translate both (a) his being left behind in the Rif (the zoom on his feet walking the grass of the outskirts of the city of Nador, in the shade of tall reeds that half-conceal a garbage dump ties him to both the land and his new status as “dumped”); and (b) his dreams of cinematic escape (he picks up strips of film).

The film strips look incongruous at first: they do not make sense as superfluous objects wasted by a consumer society that is foreign to the impoverished region in 1975. But the image of Amar rescuing strips of discarded film recurs on six different occasions throughout the film, producing several distinct meanings each time.

Semantically, this repetition with variation works like a jazz trope: each visual “refrain” both reflects the original scene and produces added meaning that has been gathered from the filmic narrative in between the iterations. If at first, the protagonist is intrigued by them and collects them furtively, as a new treasure to be deciphered later, he gradually makes sense of them (as he becomes more adept at film viewing) until he masters them and recreates a film from the fragments he has thus scavenged. This apparent story of film recycling does not provide a mere subtext or subplot to the main narrative, but forms a crucial part of its very structure, especially if we see the discarded film in Stamian terms, as polysemic and polyvocal: Amar literally becomes a filmmaker thanks to the trashed film he rescues.

There is a literal explanation to the throwing away of film: Juan, the projectionist, keeps complaining about the poor quality of the Rif’s projector, which gets too hot and routinely burns film through. He then has to quickly cut off portions of film to reassemble a truncated version of the original moving picture. Towards the end of the film, Amar builds a crude projector at home and, having recycled and put together his finds, screens an entire newsreel sequence for his friend Saïd. The resulting homemade flick turns out to be official propaganda about the Green March, the first screening of which had been brutally interrupted at the Rif when the projector suddenly once again burnt the film. (Thereby causing a nationalistic riot in the theater, so convinced was the Rifan audience of malicious sabotage on the part of Juan the Spaniard!)

However, a slightly different picture emerges when taking a bird’s eye view of Amar’s film-gleaning habit: the movies we see at the theater are of two kinds: (a) Indian films in Hindi (with no subtitles); and (b) the Ministry of Communication’s newsreel about Hassan II’s response to the Spanish-Moroccan territorial conflict (in French and in Arabic). Hence, the images projected onto the screen are all produced in the Global South: news produced by Morocco and fiction produced by India. What Amar collects is either Indian subcontinental fantasy or the officially sanctioned news of the Kingdom, that is, two sets of films (third-world fiction and third-world news archival footage) ignored by the West.

In the end, then, the original filmic trash becomes polysemic and multivocal in various ways: excerpts of dumped film are precious to Amar, the student of cinema, and visually restored to the screen; Indian colorful rom coms, alternating with the black-and-white newsreels that describe a Moroccan reality that directly affects the people of Nador, become the subtext of the Rifan film caught between an Indian dream (and not a French or a Spanish one) and the political reality of Hassan II’s reign―just as Amar is caught between his cinematic dreams and the sordid, dark reality of his orphaned present in Nador.

A NEW/FRESH VISION OF TRANSNATIONAL CINEMA

How does this new perspective on cinema shift our perception of transnational cinema in Morocco?

REVERSAL 1: AMAR’S INITIATION FROM LEARNER TO DIRECTOR

Both initiations out of childhood and into film viewing are intimately linked: “I wanted to show how Indian cinema in the seventies, when there was nothing for us (apart from street violence), allowed us to travel or flee this violence that was both political and social.” What starts as a form of escapism quickly morphs into something much more significant as the child experiences both an unexpected breath of freedom and the ebullience of shared emotions in front of the wide screen: “I tried to underscore how films in general can give you a kind of freedom, a way to sing together, experience emotions together, even if, once outside the movie theater, we might fight.”19

In his press kit, the director makes it clear that part of Adios Carmen is autobiographical: Carmen did exist (in fact the neighbor who took little Mohamed Amin to the movies was named Carmen) in his native town of Zghanghan, where he spent his childhood and teenage years. Yet Benamraoui’s film is not so much a nostalgic film about his individual childhood as it is an overview of the conditions of children of emigrant parents in the Rif and of cinema practices at the time.

Here, the sociologist of cinema provides us with images of the film entertainment of the time in Morocco to which Western audiences have not had access. Throughout Adios Carmen, we discover some of the contemporary Hindi films that were popular, the excerpts of which are directly imported into the filmic narrative: Aag Gale Lag Jaa (Manmohan Desai, India, 1973), Yaadon Ki Baaraat (Nasir Hussain, India, 1973), Sholay (Ramesh Sippy, India, 1975), Khandan (A. Bhimsingh, India, 1963) and Bobby (Raj Kapoor, India, 1973). The filming-from-below idea here extends to the initiation to cinema that, for young Amar, is not a crash course in European or Hollywood cinema, but a serious introduction to the popular movies of India, one of the other non-aligned countries in the 1970s.

Beyond the economic choice for Moroccan movie-theater directors to program Hindi films at the time (they were cheaper to import and circulate than the films from the First World; and although they were not subtitled, the plot lines, the music and dances, as well as the hyperbolic emotional displays, were easy to follow), quoting the films in Adios signifies differently from quoting, say, Jean-Luc Godard, for a diasporic subject. It redraws the borders of the entertainment world away from a North-South direction, into a South-South one. European or Hollywood cinemas do not seem to exist in the consciousness of the diegetic audience. It simultaneously underscores the global reach of Hindi cinema and the readiness for the audience to consume it as a form of satisfying entertainment. The fact that it is a Spanish woman who initiates Amar to Hindi film is one more wrinkle in this surprising film. Yet, the choice of having the intervention of a female Westerner in the film initiation of a non-Western boy is realistic for two reasons: Carmen sells tickets at the theater and she is the only woman in the picture house. At the end of the film, we learn that little Amar has become grown Mohamed Amin, who has mastered storytelling techniques and has put together a film on his learning all about film and on resilience, as we hear Mohamed Amin Benamraoui’s own voice off screen revealing the post-film narrative:

Saïd emigrated to Spain after the Rif cinema got demolished. Carmen comes back every two years to visit her mother’s grave. Since I left, I very rarely go back home. Since then, Carmen and I have never crossed paths again.

The omniscient voice that offers the comment is the aural image of a consciousness that speaks from above. It echoes the scene of Carmen’s departure in which Amar refuses to bid her farewell and hides on the terrace from which he watches her leave. The transformation that has taken place in the character is here complete: he no longer takes the view from below―and he is no longer shot from foot to knee―but has an aerial view of the situation, of the courtyard of the house where he lives, that Carmen crosses one last time before exiting the frame and Amar’s life. The entire scene is shot from his high angle. This 180-degree flipping of the perspective is a visual precursor, for the revelation of Mohamed Amin Benamraoui’s voice over a few scenes later. By the end of the film, Amar has become not simply a film viewer, but the seed of a filmmaker, the director, the one who reorients the gaze of others.

REVERSAL 2: THE TRANSNATIONAL SEER SEEN

Another innovation in the film is the way it portrays a cinema audience. Hence we are not simply initiated, as an extradiegetic viewer, into the Hindi films of yore, but also into the film-viewing practices of a 1975 audience in the Rif. The camera follows the viewers lining up to buy tickets, zooms in on them fighting to get in, and then on Bount the scammer who buys tickets and terrorizes people; you see them leaving their bicycles in the care of Saïd right outside the theater. Yet the men flock to the Rif to see romantic love stories that end with lovers reunited, everybody dancing, stories of abandoned children surviving and finding their mother again (!), stories of poor people getting chances in life after countless setbacks. Suggestive Oriental dancing elicits quite some noise in the theater, but sentimental sequences also produce silent weeping in the audience: not just Amar’s but grown men’s too (the same grown men who had been fighting and insulting one another just before the movie started, outside the theater).

Benamraoui aims his camera at the diegetic viewers in the Rif in long and medium shots that reveal the flickering reflections of the screen on their tearstained faces. The only face that appears clearly in a close-up is Amar’s. Amar’s unfiltered response to the screen matches the intensity of his scopophilic desire: he laughs with abandon, cries big tears. But when the camera slightly pans out, the surrounding adults’ emotional response to the (for us) unseen screen is just as intense. Although the other diegetic viewers in the cinema never come into view in isolated portraits but in a group with undefined faces, they all express shared emotions.

This reversal of the camera direction on the seer rather than the seen evokes Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami’s Shirin (2008), with its series of close-ups on 114 actresses from Iran and on French actress Juliette Binoche crying as they watch the adaptation of the twelfth-century romantic Persian epic of Khosrow and Shirin (Khusraw u Shirin). Here, the extradiegetic audience only has access to the film Shirin that is shown to them aurally, through its soundtrack. In fact, the entire visual track consists in a succession of faces from a female-only audience facing a film within the film, never to be seen by the extradiegetic viewers. Kiarostami stated that he had wanted Shirin to be his last film (it was not) with the intent of showing what now ultimately mattered: an isolated seer of film, detached from her neighbors. Face to face with my double, a viewer fully engrossed in the contemplation of a film, I, the extradiegetic viewer, become able to share the emotions revealed on her face, no matter what the original film that produced the original (diegetic) emotion. This, in turn, creates a new type of empathy between the extradiegetic seer and the diegetic one: “This convoluted interaction of gazes generates what I propose to call a cinema of ethical intimacy, an existential space of spectatorial emancipation and optic communality.”20 Such “ethical intimacy” deeply connects the fictitious seer and the experiential one on an individual level. The process of identification is one on one―in fact, Kiarostami filmed each actress in Shirin separately. The edited string of portraits tricks us into imagining a synchronous audience that actually never convened. The illusion of cinema here stretches farther than usual to include yet another grand illusion: that of a sharing public.

Benamraoui’s film offers a gender twist on this “optic communality” since the diegetic audience is male only, and does not isolate each and every one of his diegetic viewers the way Kiarostami did. Amar’s viewing companions, as they watch their film, feel free to express their sentiments in the protective space of the dark cinema, during the suspended time of the screening. In that, the director projects his own empathy in filming the hidden side of often bombastic, violence-prone males in 1970s Nador: after the brutal behavior they exhibit in the public sphere, on the streets, the privacy of the Rif theater gives them permission to no longer follow the rules of their macho society that they abide by in the daylight. They can finally cry. . . Both directors, then, show that the space and time of film viewing are sites of emotional freedom, a type of freedom that is denied to women in post-1979 Iran and to men in 1970s Rif. Although very different in their goals, Shirin and Adios share the intimacy of an emotional release that is allowed, indeed longed for, and finally bestowed by film. Even if each viewer reacts individually to the projected narrative, the sharing of film-induced sentiments and of the possibility to express them has a cathartic ritual quality: “It is also about the collective ritual of going to the movies and the visceral dimension of that event.”21

Finally, framing the diegetic audience watching a film has a similar effect on the extradiegetic audience as it illustrates the “optic communality” that unites diegetic and extradiegetic audiences in equal, non-hierarchical positions. I, the extradiegetic viewer, am given to watch my avatar in both Shirin and in Adios Carmen.

In the end, then, the film gives homage not only to the Hindi cinema of the past, but also to the audience of this cinema in Nador. Here again, then, the diasporic filmmaker flips the camera to turn it towards the audience, an audience now defunct (much like the actors who are on screen have long ago disappeared by the time we see the film) but an audience united by the foreign cinema of India, and a participatory one: the viewers sing along (phonetically) with the protagonists, move their arms in rhythm with the dancers on screen, cheerfully responding along a call-and-response model to the narrative on screen.

The interfilmic link between Kiarostami and Benamraoui in this cinematic treatment of the spectator as the object of the gaze further exploits the developing world cinema in which Benamraoui consciously inscribes his work. In the film-screening scenes, directing the camera frontally to the intradiegetic audience achieves a three-way cinematic symbiosis between India, Morocco, and Iran, as the Hindi film’s shadows flicker onto the faces of the Rifan audience shot in the manner of the Iranian master.

RECYCLES AND TRANSMOGRIFIES TRANSNATIONAL CINEMA

After Carmen has left, and Amar has collected enough trashed film, he recycles the strips into a reel. He builds a crude projector and he invites Saïd to see the result. The scene is moving on several levels: it evokes the last scene of Cinema Paradiso (Italy, 1988), with a gentle wink at Giuseppe Tornatore’s classic film; it shows cinema as a liberating venue not only for Amar but also for his friend Saïd, away from the violence they have been subjected to; on a meta-cinematic level, it looks at discarded film not as censored (as the kiss scenes had been on the order of the church in Cinema Paradiso), but as material to fashion film anew. The resulting montage contains a telling newsreel as its voice over suggests, thus importing a national perspective into the individual one:

The Green March was a success. Spain is our ally. There is no winner and no loser. The negotiations between Morocco and Spain must take place in a climate of friendship. [King Hassan II:] “Morocco and Spain must rebuild their relationship afresh.” Yesterday, Morocco celebrated the second anniversary of the Green March and the King made a speech.

In that, it mirrors Benamraoui’s own recycling practice in his film as he imports both Hindi film and CCM newsreel to tell a story that is both private (Amar’s initiation to film thanks to Carmen) and political (the story of Rifan emigration and its overlooked victims). With this last newsreel, it is apparent that the politics that separated Carmen from Amar have become a moot point: Spanish and Moroccan emigrations are alike, and the fate of the émigrés is difficult for everyone, not just for Rifans or Moroccans in Europe.

Through Carmen, I also wished to broach the topic of the Spanish immigration in Morocco. It is seldom discussed. And yet, it was very real and presented many similarities with today’s Moroccan immigration to Europe. . . . It is a reciprocal emigration . . . the Spanish fled the civil war and Franco’s regime, the Moroccans fled the repression by the authorities and poverty. . . . This story can be linked to many other immigration stories, wherever they take place in the world.22

The film does not exclusively center on an Amazigh story of emigration: it includes the tale of another diaspora, thus adding a new global dimension to Maghrebi diasporic cinema usually dedicated to representing the emigration and immigration of its own community only.

Furthermore, Amar’s final montage reveals a new type of cinema that includes, in its very makeup, a somewhat straight meta-cinematographic reflection. If Benamraoui has intertextually woven flashes of various other cinematic traditions in his main filmic narrative, he does not dwell on any of them for too long. Rather, he dances from one to the next―thus being at all times an Amazigh director, an authentic “free man”! In that sense, not only has he successfully, completely de-orbited away from “francophone” cinema, or from French, Belgian, or European cinema broadly construed, but also has refused to give allegiance to others. His is a transvergent path that picks what he needs along the way (e.g., newsreels from the CCM) and takes his finds somewhere else, just as Amar does on screen. His path is full of surprising twists and turns along the way in the narrative he constructs, the way he films, the language(s) he uses to make a transnational film for an audience that extends beyond its Rifan diasporic viewers seated in the first row. His film offers a vision of new diasporic cinema that is located outside the frame of Moroccan seat of Arab power, outside the frame of France or Belgium, in constant traffic between very local cinema (one could call it “Rifan”) and a third cinema brand of cinéma-monde. As such, Benamraoui’s film enters in dialogue with a shared polymorphous cosmopolitan history: the history of global migration; the story of human abandonment and resilience. And seeing the other seeing, seeing the reflection of his film-induced trance, experiencing his emotional aura, if only for ninety minutes, is one surprising entry to a truly cosmopolitan understanding of the world. At a time such as ours, when nations erect walls and refuse entry to displaced populations, it is a welcome, mesmerizing call for empathy and a reminder of how the cinematic imagination can empower viewers.

NOTES

Special Mention, Dubai International Film Festival, December 2013; Best First Film, and Best Second Male Actor, National Film Festival, Tangier, Morocco, February 2014; Best Film, Scientific Award and Best Second Male Actor, Festival International de Cinéma et Mémoire Commune, Nador, Morocco, May 2014; Best Scenario, Festival du Cinéma Africain, Khouribga, Morocco, June 2014; Golden Screen (first prize), Festival Écrans Noirs, Yaoundé, Cameroon, July 2014.↩︎

Diasporic cinema has been alternatively qualified as “beur” by Carrie Tarr in Reframing Difference: Beur and Banlieue Filmmaking in France (Manchester & New York: Manchester University Press, 2005); as “postcolonial immigrant” by Roy Armes in Postcolonial Images: Studies in North African Film (Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2005); then as “post-beur” by William Higbee in Post-Beur Cinema: North African Emigré and Maghrebi-French Filmmaking in France Since 2000 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013); “accented” by Hamid Naficy in An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking (Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001); and finally “transnational” by William Higbee in “Locating the Postcolonial in Transnational Cinema: The Place of Algerian Émigré Directors in Contemporary French Film” (in Modern and Contemporary France, 15, no. 1, French Cinema (2007): 51–64); and in Higbee & Song Hwee Lim, “Concepts of transnational cinema: towards a critical transnationalism in film studies” in Transnational Cinemas (1, no. 1, 2010: 7–21.).↩︎

Liev Spaas, Liev. The Francophone Film: A Struggle for Identity (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000).↩︎

See Bill Marshall, “Cinéma-monde? Towards a concept of Francophone cinema,” (Francosphères, 1, no. 1 (2012): 35–51) and Florence Martin, “Cinéma-monde: De-orbiting Maghrebi cinema” (Contemporary French Civilization, 41, no. 3-4 (2016): 461–76).↩︎

See Josefa Laroche, and Alexandre Bohas, Canal + et les majors américaines: une vision désenchantée du cinéma-monde (Paris: Éditions Pepper, 2005).↩︎

Marshall, “Cinéma-monde?”↩︎

Martin, “Cinéma-monde,” 473.↩︎

Naficy, An Accented Cinema, 18.↩︎

Ibid., 19.↩︎

“Today, roughly half of Morocco’s population identifies as Amazigh. . . Hard numbers of Amazigh vary widely, ranging from as high as 60 percent to as low as 30 percent of the Moroccan population.” Graham H. Cornwell & Mona Atia, “Imaginative geographies of Amazigh activism in Morocco,” Social & Cultural Geography 13, no. 3 (May 2012): 259.↩︎

The Rif region is also (at the time of writing) the seat of an active political movement known as the Hirak. The movement started in the city of Al Hoceima in October 2016, after a non-registered fishmonger was crushed to death in a garbage truck in which he had jumped to save the fish the police had just confiscated from him. This set off a series of demonstrations, against the marginalization of the Rif by the makhzen in Al Hoceima as well as in other urban centers throughout the Kingdom that were brutally stifled.↩︎

In particular, he worked for six months on the TV program Sindbad and joined the team of the cultural TV program Dunia in 1998–1999.↩︎

“Le berbère et l'arabe dialectal traduisent la culture populaire, tandis que l'arabe classique, le français et l'Islam représentent la culture du savoir. Dans ce contexte multilingue et multiculturel, la légitimité de l'Etat est largement basée sur la culture écrite qui est étroitement liée au pouvoir.” Moha Ennaji, “L’Amazigh porteur de diversité culturelle au Maroc”, Le Matin, 14 mars 2005, http://lematin.ma/journal/2005/L-amazigh-porteur-de-diversite-culturelle-au-Maroc/51684.html.↩︎

“Je me rends compte qu’en tamazigh, ma langue maternelle, il y a des choses très fortes pour moi en tout cas et j’arrive à aller chercher les émotions universelles, à chercher les choses qui nous appartiennent à tous, mais dans ma langue.” Mohamed Amin Benmaraoui interviewed by the author, 6 May 2016, Tangier.↩︎

See Hein De Haas, Hein & Tineke Fokkema, “Intra-Household Conflicts in Migration Decision-making: Return and Pendulum Migration in Morocco,” Population and Development Review, 36, no. 3 (September 2010): 543.↩︎

After the independence of Algeria and Mauritania, borders were redrawn, and Western Sahara became a zone divided and administered by three governments: Algeria, Mauritania, and Spain still held on to a portion of the territory, south of the Moroccan border. In 1975, Hassan II, needing to stifle opposition at home and to unite his people around the makhzen, seized the opportunity of a weakened Spanish government, and invited his subjects from all corners of the kingdom to gather and march across the Moroccan southern border with Spanish Sahara, so as to liberate their Sahrawi brothers and reclaim their “historically Moroccan territory” from the boot of the Spanish occupier.↩︎

Faux pas/False Step (2003), an homage to Evelyne and Abraham Serfaty who were victims of Hassan II’s policies during the years of lead, is entirely shot at that level and dialogue-free.↩︎

Robert Stam, “Palimpsestic Aesthetics: A Meditation on Hybridity and Garbage,” in Performing Hybridity, eds. Joseph May and Jennifer Natalya Fink (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1999), 76.↩︎

Mohamed Amin Benmaraoui interviewed by the author, 6 May 2016, Tangier.↩︎

Asbjørn Grønstad, “Abbas Kiarostami’s Shirin and the Aesthetics of Ethical Intimacy,” Film Criticism 37, no. 2 (2012): 25.↩︎

Grønstad, “Abbas Kiarostami’s Shirin,” 30.↩︎

Mohamed Amin Benamraoui, “Note d’intention du réalisateur,” Adios Carmen: Dossier de Presse (my translation) (Brussels: Thank You and Good Night Productions, 2013), 6.↩︎