Donna West Brett

AN AESTHETICS OF DISRUPTION: UNSETTLING THE DIASPORIC SUBJECT1

Abstract

In her writings and video works, Hito Steyerl presents a disruptive tension between the pervading sense of being under constant surveillance and the desire not to be seen or to be invisible. In observing the omnipresence of the camera, Ariella Azoulay also considers photography’s capacity for inscription and surveillance. This withdrawal from representation disrupts our expectations of the photographic process, in which a contract is made between the sitter and the photographer, that their likeness will be captured on the photographic emulsion or digital pixels, a likeness that can be observed, critiqued, printed or shared. Disrupting the political and social ontologies of photography undoes and unsettles what photography is and what it should do; hence Azoulay and others ask, What is a photograph? This essay takes these concepts as a point from which to consider an aesthetics of disruption and the conditions that cause a subject or an image to withdraw, to hide, or to disappear, in the work of three artists from the Arab diaspora: Cherine Fahd, Joana Hadjithomas, and Khalil Joreige.

In The Wretched of the Screen, Berlin-based artist and filmmaker Hito Steyerl interrogates what she calls the poor or latent image; the debris of audiovisual production, the JPEG washed up on the shores of a digital economy that testifies to the violent dislocation and displacement of images.2 For Steyerl, poor images can also be latent images, they are illegible like a worn or damaged negative, the subject long faded into obscurity and withdrawn from representation.3 The more we are seen, photographed or observed, we increasingly disappear in both the real and cyber worlds because as Steyerl puts it, “photographic or moving images are dangerous devices of capture: of time, affect, productive forces, and subjectivity.”4 In her writings and video works, Steyerl presents a disruptive tension between the pervading sense of constantly being under surveillance and the desire not to be seen or to be invisible. In observing the omnipresence of the camera, photography theorist Ariella Azoulay also considers its capacity for inscription and surveillance. Despite the proliferation of cameras and the number of photographs taken, Azoulay aptly observes that most of us “do not have the privilege of seeing the images they produce.”5 For many individuals, particularly those who do not control their image, “the camera is a tool that promises a picture they will never see,” as Azoulay puts it, hence their image remains latent and invisible.6

This withdrawal from representation disrupts our expectations of the photographic process, in which a contract is made between the sitter and the photographer, that their likeness will be captured on the photographic emulsion or digital pixels, a likeness that can be observed, critiqued, printed, or shared. Disrupting the political and social ontologies of photography undoes and unsettles what it is we think a photograph is and what it should do; hence Azoulay and others ask, What is photography and what is a photograph?7 In this paper I take these concepts as a point from which to consider the aesthetics of disruption and the conditions that cause a subject or an image to withdraw, to hide, or to disappear, in the work of three artists from the Arab diaspora: Cherine Fahd, Joana Hadjithomas, and Khalil Joreige.

THE CONCEALED SUBJECT

In his Denkbild “Ways Not to Be Seen” the German philosopher Ernst Bloch meditates on phenomena that he refers to as “unseeing.” As an example of how unseeing can take an object below the horizon of perception, he recounts a story of the Prussians in Paris in 1871 in search of the Mona Lisa, which had been hidden behind a wall in the Hotel des Invalides by a canny protector. As the spiked helmets burst into the junk room concealing the painting, the soldiers instead found a rare map that satisfied their objective, while a few steps away, the Mona Lisa remained hidden with her face to the wall, unseen. Bloch considers this strategy of making something unseeable as diverting the covetous gaze from the main objective by satisfying it with something less; the gaze is shrewdly satiated before it finds it target.8 The concept of unseeing resonates with various strategies of camouflage such as visual deception, concealment, blending, or the psychological effect of hiding things in full view.9

These strategies are employed by Australian/Lebanese artist Cherine Fahd as a means to question or to interrogate the camera’s ability to both record and subvert the subject. Drawing on minimalist principles and the formalist construction of figure and ground in her photographs—many of which are self-portraits―she nevertheless engages with erasure of the subject and the occlusion of vision.

Acting as a cipher for art-historical tropes, Fahd consistently models herself as a figure that is erased or obliterated as can be seen in several photographic series, such as one where she records an attempt to form a bust of herself from clay (figure 1). In I need to make a bust (head sculpture) for art and I don't know how to do it and it can't be just any head it has to be mine (2011), Fahd struggles to form a loose representation of her own head in a performative act that continues throughout the series of images. Here, Fahd undoes the idea of a traditional sculptural rendition and instead disrupts both the subject and its depiction. Fahd forms and unforms the lump of clay from a position below the table, where she can neither be seen (other than her arms), nor can she clearly see the form being shaped before her. The fumbling and awkward movements made as the cherry-colored clay is pushed, pulled, stretched, and molded imply moments of frustration and desperation in forming a likeness. The series of photographs and the corporeal actions depicted also unsettle our expectations of photographic portraiture, in which we expect an exchange of gazes between the sitter and the beholder.

In unsettling the essence of representation Fahd often pictures herself in the form of a white space or as a shadow, where she becomes concealed or hidden. In the series Plinth Piece (2014), rather than her own corporeal form displayed on the plinth, she is both molded from and made invisible by the photomontaged application of play-dough, her disappearance made apparent by the bruising marks of the roughly hewn form that forces the subject into a two-dimensional plane. Here, Fahd creates a facade that reimagines the body as overwhelming flesh.10 In one photograph from the series, (Plinth Piece, Study for a Woman Bitten by a Snake), Fahd lies strewn across the plinth, the white play-dough almost completely obscuring her, bar a lock of hair, a glimpse of skin, and a portion of her right foot (figure 2). Recalling Auguste Clésinger’s sculptural rendition, Femme piquée par un serpent (Woman bitten by a snake) of 1847, Fahd’s molded form, with its corporeal imprints, evokes the scandal afforded Clésinger’s masterpiece. The dimpled flesh at the top of the woman’s thigh reveals Clésinger’s use of a plaster cast to mold the model’s form directly from life, its intense detail revealing an acute realness that caused great offence at the annual Salon.11 In contrast, Fahd’s interpretation renders her absent. Rather than the flesh hosting the bodily traces of dimples and ample form, the clay replaces the figure, with depressed marks revealing the artist’s hand that both annuls the subject and reinforces its absent presence.

As subject, Fahd is constantly in the process of being made and unmade, formed and unformed, as if in making the image she is attempting somehow to construct herself. As a child of an immigrant Lebanese family, Fahd was convinced that she was French until a friend enlightened her and symbolically erased the subject Fahd thought herself to be.12 This concealment of her otherness through taking on the subjectivity of a desired Other has a performative re-creation or reimagining of self at its core. Here, the grounding of identity as subject, as object, or as image, becomes―as Steyerl imagines―a crisis of, or a struggle for representation.13 The concealed body is without form and its existence becomes a mere image that is itself subject to erasure, to forgetting, and to disappearance. In another series titled Camouflage from 2013, Fahd again brings into question the notion of portraiture itself and our expectation of both representation and recognition. Obscured by color, the subject appears only in part, provoking a desire in the spectator to look beyond the surface in search of the figure. Both in this series and in Homage to a Rectangle (2015), the concealment of the body almost feels violent or violating because the corporeal form becomes “picture,” and in so doing destroys itself. As picture, the subject becomes hidden not so much by the compositional forms of paper or color but hidden or obscured by the image itself.

In direct contrast to her photographs of the public, captured in private contemplation where they are unaware of the camera, such as The Chosen (2002–2004), Trafalgar Square (2005–2006), or The Sleepers (2005–2008); her work over many years has instead engaged with occlusion of the subject. These various bodies of work include Shadowing Portraits (2014–2016), and Hiding: Self Portraits (2009–2010), in which Fahd photographed herself in her home each day for one hundred days, during the last stage of her second pregnancy, and in the weeks afterward. In each photograph Fahd’s head or entire body is either covered or occluded to some extent, an act of veiling that ranges from quizzical, to poignant, to mildly hysterical, even whimsical. These impromptu moments that interrupt domestic blandness include witty moments when a towel, nappies, balloons, a fridge door, newspapers, a box, a plastic bag, a lampshade, or any other available item obscure both mother and child. The series Hiding and 365 Attempts to Meditate (2011) possess both a witty overture and a deeper interpretation, which allude to the questioning of identity and the role of motherhood.

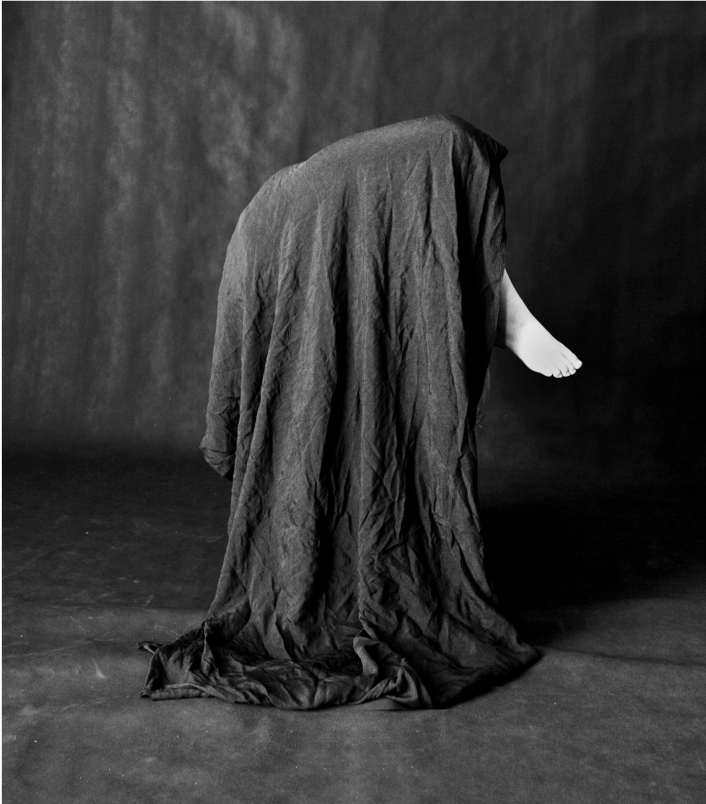

The act of veiling continues throughout much of Fahd’s oeuvre, most poignantly in a recent series titled Ephemeral Sculpture from 2013, where she again photographs herself as an obscured object. As in the Plinth series, she becomes sculpture, alluding further to the aesthetic trope of figure and ground. Here, however she intensely evokes the subject as Other. Positioned in the studio against a dark background and draped in crumpled black silk, Fahd becomes an elusive figure reminiscent of a classical sculpture in museum storage. In turn, the images also evoke nineteenth-century studio photography, and anthropological studies of other cultures. As art historian and anthropologist Christopher Pinney observes, the anthropological lens has been critically scrutinized in terms of its colonial past particularly in terms of the relationship between images and culture, and images and power.14 As he notes, it was Walter Benjamin who developed the insight into how photography deposits an aura into the face and where “the subject grew into the picture, in the sharpest contrast with appearances in a snapshot.”15 The growing into the picture of the subject forms a presence that photographic historian Elizabeth Edwards argues is embedded in the photograph. Like Benjamin, who in understanding photography as an image that seemingly grows from or emanates out of the very depths of the image substrate, Edwards contends that presence “is traced into the very materiality of the photographs, into its chemistry, and now its electronic bytes. It is the ontological scream of the medium—it was there, present.”16 As Edwards argues elsewhere, in setting specific modes of imagining and in structuring global relations, colonialism not only shaped identities but its images saturate the archives, and in so doing they determine patterns of visibility and invisibility.17

One photograph from Fahd’s series titled Ephemeral Sculpture no. 1 with Fan undoes the picturing of the Other and belies its first appearances as an archival, anthropological, or studio-portrait photograph with the unsettling presence of a cheap plastic standing fan (figure 3). Unlike the figure that appears to float above the surface of the floor, the fan is firmly rooted to the ground, its four ugly legs, long neck and functional head denoting a sturdy purpose. Its presence shifts the picture back into the now with a disquieting jolt. But what of the figure? While the subject in Ephemeral Sculpture no. 1 with Fan is largely obscured by the black silk cloth, bar the right arm that hangs loosely to the side, it is still recognizably a human figure, albeit floating above the floor. In two other images that do not feature the fan, the figure (a young gymnast) is further abstracted, less recognizably a body at first inspection (figure 4). Their corporeal abstractness, being both ephemeral and performative, forms a curious sight reminiscent of the photographs taken by Paul Richer of experiments by the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893) at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, or indeed photographs taken by psychologist Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault (1872–1934).18 Their mutually controversial scientific investigations into disorders of the mind are of interest to scholars of the visual field because of the photographic intrusions enacted upon their subjects. While Richer’s photographs recorded Charcot’s hysteric patients under the influence of hypnosis, resulting in startling photographs of women in extreme physical positions of catatonic states, Clérambault studied both the disorder of erotomaniacal delusions and autoerotic passions related to fabric fetishism, and undertook an extensive photographic project of drapery.

Clérambault, who worked most of his career as a police psychiatrist, published various articles between 1908 and 1910, in which he presented four case studies of women who stole silk drapery from department stores.19 In each case, the women displayed autoerotic passion for the stolen silk, their illicit actions arising from intense and intoxicating arousal activated by touch. As a result of the studies Clérambault coined the term “silk erotomania,” a condition that various critics suggest reveals his own fabric fetishism. In addition to these studies and those of mental automatism and delusions of love, he also produced photographs of drapery in Morocco between 1915 and 1920. It is these photographs, forty thousand in total, and taken at the height of French colonialism, that are of interest here.20 The North African, largely veiled female subjects posed for Clérambault’s camera before a dark background, much like Fahd’s renditions. The subjects pose with arms aloft in movement, coyly framed against a doorway, crouching on the ground as in evoking a sculptural form, some lifting the edges of the veil for sunlight to cast an elusive glow around the body sheathed in cloth. Others are more abstractly framed, with any corporeal reference eliminated, which as theorist Joan Copjec observes still retain a certain enigmatic quality, “for what is thus obscured in these cases is the very prop on which the drapery’s purpose hangs.”21 In her essay on Clérambault’s photographs Copjec observes that from the fantasy of an erotic and despotic colonial cloth emerges a “fantasmatic figure—veiled, draped in cloth—whose existence, posed as threat, impinged on our consciousness.”22 While one can analyze Clérambault’s photographs in term of the colonial gaze, Copjec argues that it was also the cloth itself that drew his attention, most particularly the qualities of silk that gave it its solidity and stiffness; indeed one could argue it is silk’s sculptural qualities that arrested his gaze. In the photographs, we see cloth that is not “elaborately embellished, symbolically erotic, but a material whose plainest best-photographed feature is its stiff construction,” as Copjec puts it.23

A selection of these images by Clérambault, that so evocatively and erotically picture the draped forms of Arabic men and women, feature in Fahd’s home after she collected them in Paris in 2003. Here, they have remained a latent visual force for a decade before rising out of the imaginary and into Fahd’s haunting photographs. For Fahd, her series addresses the relationship between sculpture, performance, and photography, where the photograph is staged and unstaged, both as an image and an object. As Fahd considers, “in this instance photography is used to convey a sculptural form by fixing to image what is short-lived as a performance.”24 Taken in a traditional lighting studio the works draw not only on Clérambault’s complex renditions but also on classical draped figuration in sculpture and painting, reinforcing Fahd’s continued referencing of art historical tropes.

For Fahd, a photographic portrait fixes the self to an unchanging image, an image fixed in time, unlike the self, which is forever manifold and open to change. As a concealed subject or in some cases taking on the form of a shadow, Fahd makes herself not only other but also subject to a fluidity and a slippage that is forever in the process of making; rather than a latent image, she is a latent subject. The tension present in these works engages with the desire to disappear, to be invisible from the constant gaze of being present and being seen. While Fahd images herself not just as concealed but also as veiled, more recently she has also explored the concept of visibility as dangerous, which like invisibility can be deadly, as Steyerl puts it.25 This ongoing tension between being seen and not being seen is at play in Fahd’s work as a way of thinking not just about camouflaging the self but of the inherent and disruptive dangers of visibility.

WONDERFUL BEIRUT AND THE LATENT IMAGE

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s photographs, films, and installations present various histories of Lebanon from a social and political view, reflecting on war, memory, forgotten events, and secrets. Essential to their philosophical inquiry is to investigate the ways in which violence affects images and narratives drawing on the emergence and the disappearance of images. Informing this approach to thinking about and making images were photographs held in their respective family albums of places they had never visited, but were familiar with, and that gave rise to numerous family stories with fragments of memories interlaced with seeds of mythology. These photographs act as witness to an unattainable past, and the proof of lives lived in Palestine that attest to the “existence of a memory, a culture and a way of life,” that for Hadjithomas and Joreige remain veiled and out of reach.26

Their multipart series Wonder Beirut (1998–2007) takes the city as a central point of topographical focus, a city that persevered through recent conflicts such as the Lebanese civil war (1975–1990), the 1982 siege of Beirut, and the 2006 Lebanon War—a military conflict that lasted for thirty-four days. This early series of work commenced as a response to the violence generated by the Lebanese civil war, the initial visual stimulus being a colorful postcard of “Wonderful Beirut” with its beaches and the Riviera, scenes of economic and cultural prosperity. The postcard, which was being sold in local stationery and tourism stores, bore no resemblance to the devastation that surrounded them, with the persisting image embodying a lacuna between the past and the present.27 A series of these postcards, created by the photographer Abdallah Farah, was commissioned in 1968 by the Lebanese Ministry of Tourism to document Beirut’s modernity.28 After Farah’s studio was burned to the ground at the outbreak of war in 1975, he scorched some of the remaining negatives, and in so doing, conformed his images to the damage inflicted on the city through conflict. The resultant images are burned, twisted and scarred by an external force that has changed both the surface of the image and its meaning.

In turn, Hadjithomas and Joreige have reconstructed these damaged photographs to elicit the historical tensions of the city’s past as an image of modernity, and its resultant destruction by conflict. In recreating the damaged photographs, the artists consider that their actions bring out the indexical specificity of each image in a tactile way, saying, “We wanted to return to an ontological definition of these images: the inscription of light by burning.”29 The reconstructed images, while evoking Farah’s destructive testimony, also suggest the un-photographed moments of these same scenes destroyed by the conflict. Hadjithomas and Joreige’s photographs then, recall both a series of events of photography that they did not witness, and possible photographic events that were not captured by the camera.30 In the exhibition of these works, the gallery visitor can take away any number of postcards—but instead of collecting images of Wonderful Beirut, Paris of the Middle East, they instead gather reproductions of images destroyed by the conflict between chemicals and fire.

The destruction of the city is made palpable throughout the series of distorted and damaged pictures, presenting a strange visual binary between the city prior to and after the conflict. In Wonder Beirut #6 (Rivoli Square), the city center is awash with people going about their business; cars, trams, and buses merge together on the road and customers dine at outdoor cafes, all blissfully unaware of the destruction around them (figure 5). The surface of the image is blistered, twisted, and torn with light shards penetrating the skin and shattering the view. The central building seems to sway from left to right as if in motion, while on either side the sky tears itself apart and threatens to rip the image into pieces. Here the image’s past and future are forever interlocked with the city’s fate in a violent representation. The damage to the presence of representation according to cultural critic T.J. Demos, “is not simply a matter of negative destruction, but of productive engagement, one that allows the traumatic aspects of the subjective relations to representation be confronted, rather than repressed.”31 The damage made to the image, while bearing the traces of its past, remains a latent reminder of the withdrawal of the visual in times of conflict.

During the war years Farah also took thousands of photographs of his family and the world around him. Unable to process the films, he began to put them in drawers along with a detailed description of every photograph (figure 6). The latent image remains invisible and hidden, yet the descriptive texts bring the images alive in our imagination. Some focus on his mother and her photo album—such as negative number 20, “Mum shows a photo of herself (in the Wahed studio); she is young and poses in front of Dad’s camera,” or number 21, “some photos of my sister and I dressed up as sailors.” Further descriptions conjure visual images of war at close quarters such as negative number 4, “from the roof, smoke and an explosion in the southern suburbs. The neighbors run, frightened by the noise of the explosion,” or, negative number 15, “the television showing the explosions and, behind, through the window, lights everywhere.”

What enables us as the viewer to bring forth images that evoke the descriptions is first our imagination, but second, we remember like images either from our own memories or from scenes we have encountered on the television, in newspapers, or on social media. It is therefore apt that some of the descriptions of the images include what Farah can see on the television screen at the same time he sees events happening outside his window. This double seeing is how photography works. The photographer never really sees what they are photographing; rather the screen of the camera lens mediates and doubles the view. We too experience much of current or indeed recent historical events in the same way—as poor images through screens that filter our seeing and our consciousness.

The photographer Abdallah Farah, whom we imagine observing the scenes, taking the photographs, and then painstakingly recording their content, is indeed fictitious. Rather, it was Hadjithomas and Joreige who took the photographs and wrote the powerful descriptors that now resonate in the mind as memories of something unseen and yet seem so real.32 Farah can be seen instead as a cipher for their own experiences of war and displacement, a means by which they can tell a story that enables a slippage of meaning, meaning that is disrupted by both conflict and its traces. As a photographic process that does not result in an image, the project allows for their own experiences and familiar accounts of war from friends and family to be told, for how many experiences go by in life that are not photographed, how many lives are undocumented, as Steyerl so aptly observes.

These images, now in our repository of things both known and unknown, form memories of things we never experienced and will not know or understand other than as an echo. In what way then is the experience of seeing a photograph on a screen different than capturing an image through a lens, when both experiences are delayed? This, according to Ulrich Baer, is how memories work in the first place. Photography’s ability to capture moments that had the potential to be experienced but failed to register in the subject’s own consciousness is described by Baer as being akin to the structure of traumatic memory. Baer takes up this concept from Sigmund Freud’s reflections on memory and photography, where Freud describes the unconscious as the site where memories are stored until they are developed, alluding to the delay in recognition of memories and images.33

The photographs taken by Hadjithomas and Joreige between 1997 and 2006 of daily life in Beirut only stopped with the outbreak of war. The negatives remained undeveloped with only descriptions of each snapshot representing a photographic diary that could be read but not seen. The two artists see this action as “an attempt to capture the feeling of latency that haunted Beirut, an effort to show the complexity of the city, the density of situations, the aftermath of the war and its consequences for representation.”34 The undeveloped negatives promise something that remains unresolved, with the events that the camera recorded made palpable by their absence. As Azoulay notes, not every event that the camera sets in motion results in a photograph; “When it does so, the events unfolding in the wake of the photograph will, for the most part, take place in another location altogether.”35 The expectation then that a photographic event will result in an image that is seen and shared is disrupted, and as Azoulay argues, “photography always constitutes a potential event, even in cases where the camera is invisible or when it is not present at all,” such as in the case of real or perceived acts of surveillance.36

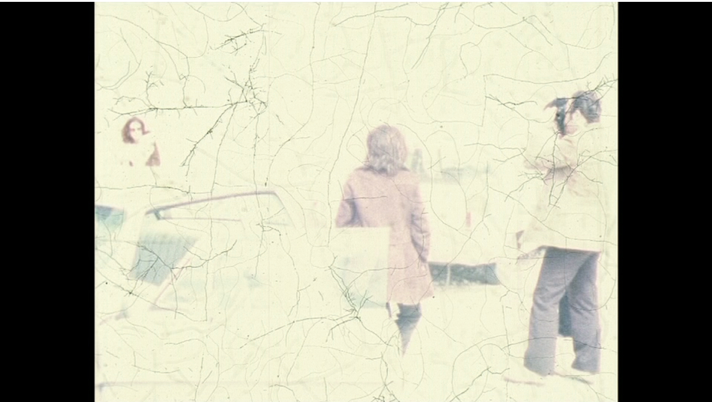

A related work titled Lasting Images (2003) is a film taken by Joreige’s real uncle, Alfred Kettaneh, before he went missing in 1985―one of 17,000 Lebanese kidnapped during the civil war and still listed as missing (figure 7). In 2001, the artists found the Super-8 film in Kettaneh’s archive which they subsequently developed. The film had deteriorated to such an extent that the images are barely visible, and the film substrate is veiled by traces of chemical reaction, its emulsion transformed into marks that hint toward images that remain absent. Out of the sea of murky shapes and squiggly lines emerge images that flicker into and out of recognition much like memories do in their oft-unbidden nature. In order to find the image, the artists had to search for traces in the substrate coaxing the wounds of chemical change to give up the latent forms that lay hidden, and then by manipulating the digitized pixels to reveal their content. The emergence and then disappearance of the image across the screen punctures the surface of our sight and much like looking toward the sun on a bright day with our eyes tightly shut, our vision is both filled with and filtered by a visual cacophony of color and light. This poor image taken by a disappeared person has a double loss that is made poignant in the efforts to restore not just the film but also the memory of Joreige’s Uncle Kettaneh.

In the resultant video reclaimed by Hadjithomas and Joreige, memories are disrupted, negated, and confused, with the image remaining as a singular piece of evidence of Kettaneh’s disappearance, which is itself a manipulated screen. Steyerl likens the state of a missing person to that of Schrödinger’s cat—which is either alive or dead. “How can we understand its conflicting desires,” asks Steyerl, “to want and to dread the truth at the same time?”37 Here, knowledge of the missing person, or indeed Schrödinger’s cat, is only confirmed at the point of observation when the state of indeterminacy is concluded.

In the Wretched of the Screen, Steyerl considers the illegible images of a photo roll that she found at the site of a mass grave in Turkey, where her friend Andrea Wolf, a German sociologist and PKK militant, had been executed after being taken prisoner. “On this site,” laments Steyerl, “even blatant evidence is far from evident. Its invisibility is politically constructed and maintained by epistemic violence.”38 The illegible images on the film roll are poor images―as Steyerl puts it, things wrecked by violence and history. “A poor image,” she claims, “is an image that remains unresolved—puzzling and inconclusive because of neglect or political denial . . . it cannot give a comprehensive account of the situation it is supposed to represent . . . they are poor images of the conditions that brought them into being.”39 The unprocessed images on this destroyed roll of film, while unable to reveal what the camera saw, show in their own materiality the violence of the actions that took place at this site. The violence enacted here is the violence of disappearance, and of invisibility, much like Hadjithomas and Joreige’s video, which attests to and constantly reinforces Kettaneh’s ongoing absence.

A more recent series titled Faces (2009) comprises a number of photographs depicting disintegrating posters of dead martyrs who either died while fighting or were political figures murdered by the regime (figure 8). The posters of the dead that covered the walls of the city were often hung high in unattainable places as they looked down toward the still-living citizens, and where the artists photographed them repeatedly over the years, observing their ongoing disappearance. Working with a graphic designer, the artists attempted to recover certain features, to draw out the latent image and traces of the person depicted, as if attempting to save them from time.40 “How do people disappear in an age of total over-visibility?” Steyerl asks: Are people hidden by images or indeed do they become images?41 These latent or lost images reflect the nature of their making and their unmaking, becoming the subject who is missing or concealed, and in so doing they become unsettled and disrupted.

Surrounded by latent or hidden images, Hadjithomas and Joreige consider how certain conditions caused these images to withdraw, “sometimes an image refuses to disappear. It comes back to haunt us. The picture that does not recede strikes us with its power and determination.”42 The persistence of these images, as noted by the artists, recalls Freud’s considerations of the latent image. As the past returns to the haunt the present, as in latent memories, photography offers a model for how this deferred temporality works.43 As Demos claims, staging the withdrawal of visuality can itself become a productive means to move beyond the aftermath of a disaster.44 Latency is, according to the artists, “the state of what exists in a non-apparent manner, but which can manifest itself at any given moment. It is the time elapsed between the stimuli and the corresponding response. The latent image is the invisible, yet-to-be-developed image on an impressed surface.”45

These photographs by Fahd, Hadjithomas, and Joreige disrupt seeing by showing us how much we do not see, or as Shawn Michelle Smith observes, “how much ordinary vision is blind.”46 A tension is made palpable here through the unsettling efforts of the artists to either obscure or uncover the subject which lies somewhere in the image, latent and unseen. While Steyerl considers the poor image as a JPEG roaming aimlessly through the internet—as a subaltern and indeterminate object—subject to disavowal, indifference, and repression, it is also an image that is unresolved, inconclusive, and disrupted.47

NOTES

The author thanks the artists for permission to reproduce their images and to Cherine Fahd for her friendship and contribution to discussions that led to this article. Research for this article was supported by a SLAM Art History Journal Incentive Award, University of Sydney, 2016. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Reframing Seeing and Knowing in the 21st Century Research Symposium, Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney, February 2017, and at Agency and Aesthetics–A Symposium on the Expanded Field of Photography, Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland, April 2017.↩︎

Hito Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), 32.↩︎

Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen, 156.↩︎

Ibid., 168.↩︎

Ariella Azoulay, Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography, trans. Louise Bethlehem (London: Verso, 2015), 19.↩︎

Azoulay, Civil Imagination, 20.↩︎

Ibid., 21. See also Carol Squiers, ed., What Is a Photograph (New York: Prestel, 2014); and Margaret Iverson, “What Is a Photograph,” in Photography Degree Zero: Reflections on Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida, ed. Geoffrey Batchen (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009).↩︎

Ernst Bloch, Traces, trans. Anthony A. Nassar (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006), 82–3.↩︎

See Donna West Brett, “Interventions in Seeing: GDR Surveillance, Camouflage & the Cold War Camera,” in Camouflage Cultures: The Art of Disappearance, eds. Ann Elias, Ross Harley, and Nicholas Tsoutas (Sydney: University of Sydney Press, 2015), 147–57.↩︎

Cherine Fahd, Plinth Piece, 2014, Galerie Pompom, Sydney.↩︎

Auguste Clésinger, Woman Bitten by a Snake, 1847, marble statue, 56.5 x 180 x 70 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.↩︎

In conversation with the artist, Sydney, 6 March 2017.↩︎

Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen, 51.↩︎

Christopher Pinney, Photography and Anthropology (London: Reaktion, 2001), 11.↩︎

Walter Benjamin, “Little History of Photography,” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, vol. 1, pt. 2, 1931–4, eds. Michael W. Jennings et al., trans. Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 1999), 514.↩︎

Elizabeth Edwards, “Anthropology and Photography: A Long History of Knowledge and Affect,” Photographies 8, no. 3 (2015): 235–52; here, 240.↩︎

Elizabeth Edwards, “The Colonial Archival Imaginaire at Home,” Social Anthropology 24 (2016): 54.↩︎

For an extensive discussion of Charcot’s images of hysteria and on Sigmund Freud’s suggestion that the unconscious is structured like a camera see Ulrich Baer, Spectral Evidence: The Photography of Trauma (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005).↩︎

See Peta Allen Shera, “Selfish Passions and Artificial Desire: Rereading Clérambault's Study of ‘Silk Erotomania,’” Journal of the History of Sexuality 18, no. 1 (2009): 158–79.↩︎

The photographs are now in the collection of the Musée de l’homme in Paris. On Clérambault also see Alice Gavin, “The Matter of Clérambault: On the Baroque Obscene,” Textile 7, no. 1 (2009): 56–67.↩︎

Joan Copjec, “The Sartorial Superego,” October 50 (1989): 69.↩︎

Copjec, “The Sartorial Superego,” 86.↩︎

Ibid., 92.↩︎

In correspondence with the artist, 3 October 2017.↩︎

See “Hito Steyerl: Being Invisible Can Be Deadly,” Tate, 13 May 2016, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/hito-steyerl-22462/hito-steyerl-being-invisible-can-be-deadly.↩︎

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, “Influences,” Frieze 147 (2012): 166–69.↩︎

Hadjithomas and Joreige, “Influences,” 166–69.↩︎

Sarah Rogers, “Out of History: Postwar Art in Beirut,” Art Journal 66 (2007): 12.↩︎

Joana Hadjithomas, Khalil Joreige and Jalal Toufic, “Ok, I’ll Show You My Work,” Discourse 25, no. 1 (2002): 90.↩︎

See Azoulay for a discussion on the tension between the photographic event and the event of photography, Civil Imagination, 227–31.↩︎

T.J. Demos, The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 187.↩︎

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, “Latent Images,” Artforum International 53, no. 9 (May 2015): 327.↩︎

Baer, Spectral Evidence, 8.↩︎

Hadjithomas and Joreige, “Latent Images,” 327.↩︎

Azoulay, Civil Imagination, 21.↩︎

Ibid., 22.↩︎

Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen, 140.↩︎

Ibid., 155.↩︎

Ibid., 156.↩︎

Johnny Alam, “Undead Martyrs and Decay: When Photography Fails Its Promise of Eternal Memory,” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 18, no. 5 (2014): 577–86. See also Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, “Faces,” in I Am Here Even if You Don’t See Me (Montréal: Galerie Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery, 2009).↩︎

Hito Steyerl, “Zero Probability and the Age of Mass Art Production,” interview by Göksu Kunak, Berlin Art Link, 19 November 2013, http://www.berlinartlink.com/2013/11/19/interview-hito-steyerl-zero-probability-and-the-age-of-mass-art-production/.↩︎

Hadjithomas and Joreige, “Influences,” 166–69.↩︎

Shawn Michelle Smith and Sharon Sliwinski, eds., Photography and the Optical Unconscious (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 13.↩︎

Demos, The Migrant Image, 186.↩︎

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, “Latency,” in Home Works: A Forum on Cultural Practices in the Region: Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria, April 2–7, 2002; Beirut, Lebanon, eds. Christine Tohme and Mona Abu Rayyan (Beirut: Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts, Ashkal Alwan, 2003), 41. See also Demos, The Migrant Image, 332n24.↩︎

Shawn Michelle Smith, At the Edge of Sight: Photography and the Unseen (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 4.↩︎

Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen, 156.↩︎