Benjamin Bruce

TRANSNATIONAL RELIGIOUS GOVERNANCE AS DIASPORA POLITICS: REFORMING THE MOROCCAN RELIGIOUS FIELD ABROAD1

Abstract

In 2004, the King Mohammed VI of Morocco announced the beginning of a series of fundamental reforms of the main state religious institutions of the country. These reforms were designed to include the over 3.8 million Moroccans living in foreign countries based on the claim that they are a part of a shared transnational religious field. This article analyzes the evolution of the main diaspora policy instruments used by Morocco abroad, especially in the case of France, such as sending delegations of religious personnel during Islamic holidays, funding mosques and Islamic associations, and providing training programs for imams from other countries. I argue that these reforms should be understood as a form of diaspora politics that aims to reinforce the Moroccan state’s ability to govern the religious affairs of its citizens and their descendants abroad with the ultimate goal of maintaining control over the religious field at home.

In the current international system of nation-states, diaspora communities pose a singular challenge. While the formation of such communities raises fundamental questions surrounding nationality, citizenship, and belonging, the policy responses that states give to these questions equally reflect the most pressing political and economic interests of the day. Diaspora communities have the ability to establish transnational links that go beyond state borders and mobilize resources that may not be readily accessible at home. As a result, depending on the views they promote and the degree of autonomy they possess, they can be perceived as a potential asset or a threat by sending and receiving state authorities.

In the case of diaspora communities in Western Europe originally from Muslim-majority countries, religion looms large as an issue of national security as well as a strategy for home state-driven diaspora politics. Islam represents a means by which to mobilize individuals in diaspora communities, whether for the benefit of home states or for transnational movements with other goals in mind. The capacity of numerous Muslim states to become involved in the religious affairs of diaspora communities in Western Europe has been possible primarily due to three factors: first, in the majority of Muslim countries, religious affairs are treated as a domain of administrative public policy, meaning that there are ministries or agencies specifically tasked with what I call here “religious governance.” Second, Western European states have been generally unwilling or unable to become involved in facilitating the local development of Islam, whether in terms of infrastructure or symbolic recognition, and have been content to rely on support provided by home states. Third, Muslims in Western Europe have historically suffered from a significant lack of local resources for the development of religious activities, meaning that they have had to actively seek, or at least be open to, donations and support from abroad.

One of the largest Muslim diaspora groups in Western Europe is the Moroccan community abroad. Estimated at somewhere between 3.8 and 5 million people, easily over 10 percent of the country’s total population, Moroccans abroad also contributed 6.5 percent of the country’s annual GDP in remittances in 2014.2 Aside from its relative size and economic weight, the diaspora communities also have the potential to serve as bases from which political movements opposed to the Moroccan monarchy can operate. As has been the case elsewhere in the Muslim world, the tone of these opposition movements has become increasingly Islamic in nature since the 1970s, as authorities repressed left-wing groups and promoted a more visible presence for religion in policy and the public sphere.

Consequently, maintaining a degree of control over Islam abroad has represented a key issue for Moroccan authorities. For decades, the Moroccan state has sought to promote their version of ‘Moroccan Islam’ abroad by sending preachers during the month of Ramadan, funding mosques and prayer spaces, and establishing direct links with Moroccan religious associations through its network of diplomatic consulates abroad. However, since the announcement by King Mohammed VI of a series of fundamental reforms of the Moroccan religious field in 2004, this involvement abroad has increased substantially.

The king’s decision to reassert state power in the religious field has explicitly included Moroccan communities abroad from the start, and leads to the main question of this article: why has the Moroccan state increased its involvement in the religious affairs of its citizens abroad as part of its reform of the religious field at home, and how can this development be understood in terms of diaspora politics? My analysis will be based on field work carried out between 2009 and 2015, primarily in Morocco and France, and will include material from qualitative semi-directive interviews carried out with state religious officials, diplomats, and local mosque leaders, as well as government documents that are difficult to obtain and often only accessible in Arabic.

As I will argue in this article, the reforms launched by the king demonstrate that the spiritual borders of the Moroccan nation are conceived as going beyond the borders of the state, which justifies a range of religious diaspora policies aimed at controlling the development of Moroccan Islam abroad. In terms of the current theoretical debates on diaspora communities and transnational politics, I will lend support to the position taken by Waldinger and Fitzgerald that “states and state politics shape the options for migrant and ethnic trans-state social action.”3 Consequently, I will maintain that these state diaspora policies have a structuring influence on Muslim transnational communities, while focusing on the example of Moroccan Islam abroad.

TRANSNATIONALISM, DIASPORA POLITICS, AND MOROCCANS ABROAD

Studies on transnationalism began in the 1970s as a subfield of international relations with a first wave of scholars concerned mostly with giving the proper weight to non-state actors that nevertheless have a significant impact on a global scale. The main studies over the next few decades focused on actors such as transnational companies, global cities, criminal networks, and NGOs, but by the 1990s a new wave of scholarship had begun that employed the term exclusively for the case of transnational migrant communities.4 It is this current of studies that has marked scholarship on transnationalism ever since, and has carried on the theoretical argument that states no longer have the same degree of control over individuals in a globalized world where communications, travel, and social interactions can bypass the borders that formerly (and ostensibly) kept national societies isolated from one another.

These studies on transnational communities and transnational social spaces have gradually merged with the work of scholars in the field of diaspora studies, where theoretical questions have revolved around identity, nationalism, and political mobilization in exceedingly varied contexts.5 Along with the convergence of these two fields of study, the word “diaspora” has evolved from a more restricted term that depended on the precondition of a traumatic origin (such as in the classic cases of the Jewish or Armenian diasporas) to a concept that applied to interconnected transnational migrant communities in general, often with the implicit idea that there is some form of shared diaspora identity that can motivate social or political movements.6 As a result, in the largest number of cases, the central questions have focused on organized movements within certain diaspora contexts, and their social, political, or economic activities directed either towards their new country of residence (“receiving states”) or towards their countries of origin (“sending states” or “home states”). In the specific case of “transplanted” Islamic movements in Western Europe, these questions have been accompanied by ideas concerning immigrant integration from the perspective of receiving states, and the role of the diaspora in facilitating religiously-motivated political opposition movements from the perspective of the home states.7 However, the active use of Islam by certain home states in their policies towards diaspora communities has received only limited attention from scholars, despite both its longevity and far-reaching impact in religious fields abroad.

The Moroccan diaspora is a particularly interesting example in this respect. On the one hand, Moroccans communities can be found in practically all of Western Europe, where they are often one of the largest and most active groups in many different currents of Islamic associations. At the same time, despite their differences in religious outlook, the majority of Moroccans remain attached to a form of nationalism that represents an opportunity for Moroccan authorities looking for inroads to influence the development of Islam in Western Europe. The diaspora includes young and fast-growing populations in countries such as Spain and Italy; however, France has been and remains its central reference point due to historical ties stemming from the colonial past, and the fact that approximately one million people of Moroccan origin live there—the largest number of Moroccans in a foreign country. As a result, it has been in France where the evolutions of Moroccan Islam abroad have been most apparent, and it is the reason why I will focus in particular on France in this article.

Aside from smaller migratory movements in the first half of the twentieth century, mostly concerning workers and soldiers serving in colonial France, Moroccan emigration abroad began in earnest during the 1960s to Western Europe within the framework of bilateral labor agreements. These agreements were concluded between Western European states, which needed larger workforces for their booming post-war economies, and North African, Southern, and Eastern European states that sought to benefit from the remittances and professional training that their “surplus” labor would gain from being sent abroad.8

Morocco signed bilateral labor agreements with France and Germany (1963), Belgium (1964) and the Netherlands (1969), and delegated the organization of emigrant workers’ affairs to the Bureau of Immigration within the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. It was during the 1968–1972 five-year plan that the government “set a goal of exporting the largest number of Moroccans possible,” primarily for potential economic benefits. Although the recession following the oil crisis in 1974 led to end of labor migration programs in Western Europe, the years thereafter would see the rise of migration tied to family reunification programs. This led to an important demographic shift as the number of women and children rose dramatically, and the once ostensibly temporary migration began to seem more and more permanent. From only 33,320 in 1962, by 1994 there were some 1,344,421 Moroccans living in Western Europe, with close to half in France.9

The home-state view of Moroccans abroad during this period was thus distinctively marked by a primary emphasis on their economic value, and secondarily by a suspicion of any organized movements abroad which might become a platform for opposition to King Hassan II and his regime. In order to counter the potential danger presented especially by organized labor and leftist political movements, the Moroccan state was inspired by the Algerian model and began to set up a network of associations called amicales (Amicales des travailleurs et commerçants, or Workers and Merchants’ Friendship Societies) within the Moroccan communities abroad in 1973.10 In this fashion, it employed its diplomatic and consular services to “oversee and rein in the more activist or ‘radical’ elements in the Moroccan worker community,” while its state security services equally monitored Moroccan students studying abroad.11

Islamic religious services abroad were by and large neglected by Moroccan state authorities during this period—at least to the extent that they did not pose any security risk to the state. According to Kepel, it also seems that the Moroccan community in France tended to “self-censor” itself, well aware that Islamist currents deemed threatening could bring on the undesired consequences of greater surveillance and scrutiny from both French and Moroccan authorities.12 Indeed, when not ignored, Islam has constituted a potential tool for surveillance and control for French authorities just as much as for Moroccans: for instance, in a memorandum issued in 1976, the state secretary for immigrant workers, Paul Dijoud, explicitly supported the creation of prayer spaces and cooperating with home states concerning cultural and religious activities, with the underlying idea of undermining the growing participation of migrant workers in unions and collective bargaining.13 Similarly, a program created for the instruction of migrant workers’ languages and cultures of origin during the late 1970s later became the main vehicle for bringing home state-approved Algerian imams to France in the late 1980s and during the civil war in the 1990s.14 In both cases, the sending and receiving states perceived Islam as a tool to control and influence diaspora communities and cooperated together with precisely this goal in mind.

Religious services were initially carried out in very local and informal circumstances: known as l’islam des caves (“basement Islam”), prayer spaces were small and make-do, often set up in inadequate spaces such as basements, garages, or industrial buildings, due to the significant lack of financial and institutional resources. An important turning point in the French context came in 1981, when a new law gave foreigners the right to create associations. Following this point, the number of religious associations rose dramatically; however, financial resources necessary for imams, mosque construction, and religious activities remained highly limited in the Western European Muslim religious fields.15

Faced with this situation, local Muslim leaders often opted to elicit financial support from a mix of foreign Muslim donors. While this decision successfully resulted in the construction of numerous mosques, it also had the side effect of introducing an element of international competition between different Muslim states with regard to Islam in Western Europe. Foreign policy considerations have been constantly at play, even in the unique case of France’s most symbolic and emblematic mosque, the Great Mosque of Paris (Grande Mosquée de Paris, GMP), which received its initial funding directly from the French state and the city of Paris. Moroccan officials seldom miss the opportunity to mention that Moroccan Sultan Moulay Youssef inaugurated the mosque in 1926, and his counsellor Si Kaddour Benghabrit was its first president (recteur), even though its management was assigned to religious authorities in Algiers. The GMP has been solidly under Algerian control since 1982, after decades of having been a source of tension between France and Algeria during and following the latter’s war of independence.16

Indeed, partially in response to their inability to secure control over the GMP, Moroccan authorities pursued another option that led to the construction of the Great Mosque of Évry-Courcouronnes, located in the southern suburbs of Paris and still one of the largest mosques in France today. Nevertheless, here as well conflicting foreign interests resulted in a complicated political process on the ground. Although the construction of the mosque was finished in 1990, the campaign to finance its construction had already begun in the early 1980s. While initially support was to have come from the Saudi Arabian Muslim World League, it was ultimately Morocco that stepped in to finance the mosque, and after a lengthy legal battle between the Muslim World League and the Moroccan religious affairs ministry, the property of the mosque was officially transferred from the former to the latter.17 The Évry mosque has since become one of the central strongholds of state-sponsored Moroccan Islam in France, and continues to receive substantial financial support from the Moroccan religious affairs ministry on a yearly basis.18

It was not until 1990 that the affairs of the Moroccan community abroad gained greater attention, with the creation of a government portfolio specifically for Moroccans residing abroad and the establishment of the Foundation Hassan II for Moroccans Living Abroad (Fondation Hassan II pour les Marocains Résidant à l’Étranger, herefter FHII). The idea for the FHII had been raised already in 1986 with the goal of strengthening ties with Moroccans abroad and reinforcing their cultural and religious identity.19 During the 1980s, there had already been groups of imams sent abroad from Morocco to provide religious services for the month of Ramadan, but the FHII would prove to be a better instrument. The number of imams sent abroad during Ramadan remained stable at around sixty during the 1990s and a program was established with the goal of funding a select number of imams permanently based abroad.20 Additionally, the FHII became an important source of funding in the religious field for Moroccan Muslims abroad, notably providing the financial resources necessary to finish the Great Mosque of Évry-Courcouronnes as mentioned above, as well as becoming a source of religious publications.

A “striking reversal” of the Moroccan state’s policy towards its communities abroad occurred during the 1990s: instead of discouraging naturalization and perceiving them as a threat, the Moroccan state began to “court its diaspora” and encourage dual citizenship with the idea that it could help migrants’ ability to serve as both a source of economic remittances as well as a political tool for the Moroccan state.21 Ragazzi has argued that this policy shift is part of a broader evolution in how states conceive of their citizens abroad, leaving behind “disciplinary” or “liberal” forms of governmentality that focus on controlling the population or its economic production (respectively), and moving towards a “neo-liberal moment [of] diasporic governmentality” in which states pursue “global nation” policies that foster new forms of “diasporic” or “transnational nationalism.”22 Indeed, since the policy shift of the 1990s, Morocco has been at the forefront of this new “diasporic governmentality,” and it has been as a part of this new approach that Islam and religious activities have acquired a unique relevance as a means to reinforce relations with the communities abroad.

RELIGIOUS GOVERNANCE AND TRANSNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FIELDS

As mentioned above, the term “religious governance” refers to the administrative action taken by states with regard to activities specifically classified as “religious,” most notably by specialized ministries or agencies of religious affairs. My preference for the term “governance” derives from the work of scholars such as Veit Bader, who argue that it has the advantage of focusing attention on “regulation or steering, guidance by a variety of means, not only by rules” and on “more actors and modes of coordination in the perspective of regulation.”23 Even in the case of states that have designated rules for the administration of religious activities, such as Morocco, governing a religious field requires a broader array of tools and strategies than solely public policy initiatives, especially when it comes to governing a religious field that extends beyond the state’s boundaries.

The concept of “religious field” draws on the work of Pierre Bourdieu as well as Max Weber, and views religion as a symbolic system that can “speak of power and politics, that is to say of order […], but in a wholly different way,” and that can evolve into a “relatively autonomous religious field” in which one finds “the constitution of specific instances that are conceived for the production, reproduction or distribution of religious goods.”24 These religious instances (or actors) derive their authority from different sources of legitimacy than actors from political, cultural, or economic fields, though there are often cases of overlap. Furthermore, following Weber’s classification of types of authority, state religious officials generally only rely on traditional and legal-rational forms of authority, while remaining highly suspicious of non-state charismatic leaders who might challenge the established order.

When these concepts are applied to the religious fields of Western Europe, an initial observation is that there are very few (if any) foreign Islamic figures or institutions that are respected equally by all European Muslims regardless of their country of origin, attesting to the importance of national background for understanding questions of religious authority. At the same time, the lack of local traditional or legal-rational instances of religious authority means that it is often charismatic religious figures, some of whom propagate radical or violent viewpoints, who succeed in attracting Muslims frustrated with the existing religious hierarchies. For states such as Morocco, this potential threat is one of the primary motivations for expanding their presence and attempting to take greater control of the “production, reproduction or distribution of religious goods” in the religious field abroad.

Following the aforementioned research on transnationalism and migration, this article argues that these religious fields should be seen as “transnational social fields,” that is to say “a set of multiple interlocking networks of social relationships through which ideas, practices, and resources are unequally exchanged, organized, and transformed” that exists between two or more countries.25 Such a holistic understanding of the field helps in better understanding the reality of migratory experiences, thereby avoiding many of the inherent dangers which arise from methodological nationalism.26 At the same time, the national delimitation (“Moroccan”) I use for this religious field carries with it its own perils; namely, over-emphasizing the importance of national origins at the expense of supra-national (e.g. pan-Arab) or sub-national (e.g. the Rif region) frames of reference. Nevertheless, similarly to Elahmadi, I use this delimitation due to the existence of specifically Moroccan national religious institutions, forms of religious organization, and historical traditions, all of which contribute to a larger imaginary associated with ‘Moroccan Islam,’ and constitute the backdrop for the current state-led political project emphasizing Malikism, Ash carism, and Sufism (for more, see the following section).27

Accordingly, I posit that there are numerous transnational religious fields that correspond to other migratory contexts, drawing on shared national, ethnic, or linguistic backgrounds, and that these fields can intersect and overlap with another depending on local, regional and international dynamics. For instance, alongside the Moroccan case, another clear example in Western Europe is the Turkish religious field.28 General speaking, the same Turkish religious currents can be found in all the countries where there is a significant Turkish population, and— once again similar to the case of Morocco—political and social changes in the home country can have a direct impact on the relationship between these religious currents abroad.29

It is precisely in this fashion that the transnational religious field can become a vehicle for “diaspora politics” or “diaspora engagement policies,” which are employed by home states to strengthen bonds and maintain a degree of control over their populations abroad depending on different political or economic interests.30 It goes without saying that receiving states may become suspicious of these policies, and may perceive them as instances of foreign interference in internal affairs as well as possible obstacles to immigrant integration. At the same time, many Western European states accommodate or even encourage such policies in the Muslim religious field in the name of national security, as they are considered tools by which to indirectly influence and control the development of Islam in their countries.31

A necessary condition for a transnational religious field is a certain degree of cohesiveness, independent of the national or local context. Simply put, there must be examples of ‘Moroccan mosques’ (or ‘Turkish mosques,’ etc.) in different countries where there has been a significant degree of migration, thus underlining the continued relevance of national origin as an explanatory factor in the study of social and religious mobilization. These need not be exclusionary dynamics; indeed, it is exceedingly rare to find a mosque that permits entry solely based on nationality. However, the predominance of a certain language, dialect, or particular religious traditions often leads to a mosque becoming associated with a certain national group, a tendency that is equally influenced by the intervention of home states and other foreign actors. Furthermore, this designation may also come with all the ambiguities of that nationality: for instance, the need for Amazigh-speaking imams in certain ‘Moroccan’ mosques, or the tensions that can arise between Kurdish and Turkish members of certain ‘Turkish mosques,’ depending on developments in the home country.32

A final reason why I use “religious field” is more straightforward: it happens to be the term used by the Moroccan administration itself for characterizing the object of its reforms. In other words, the Moroccan state is directly involved in governing the “religious field” (champ religieux or al- ḥaql al-dīnī), which is conceived by Moroccan state authorities as a distinctive administrative field of action. “Religious governance” thus refers to a specific policy domain in which the state is involved in regulating, administering, and generally exerting influence over religious life. Moreover, these state policies are directed at a Moroccan religious field which includes the religious life of Moroccan migrants and their descendants living outside of state borders, meaning that they can be understood as diaspora policies and raise questions regarding “practices of sovereignty that go beyond the territorial borders that legitimize them.”33 It also further justifies the use of the term “governance,” in that the state must necessarily depend on variable networks of both state and non-state actors in order to carry out its religious policies in other sovereign countries.34

As Islam has become increasingly associated with national security concerns in Western states since the September 11 attacks in New York, and since the 2003 Casablanca bombings in the case of Morocco, the governance of Islamic religious activities has become a main concern of policymakers in both sending and receiving states. On the one hand, for Western European countries the debates on the place of Islam in their societies are usually framed in terms of fighting terrorism or promoting immigrant integration, often attempting to draw causal links between the two. On the other hand, as I will discuss in the following section, for home states such as Morocco, governing Islam abroad involves a mix of foreign and domestic interests that do not necessarily complement those of receiving states and draws on a historically much longer, and administratively more comprehensive, vision of state involvement in the religious field.

REFORMING THE MOROCCAN RELIGIOUS FIELD: THE ROYAL MALIKI-ASHCARI ANTIDOTE

When speaking of Islamic religious governance in the case of Morocco, the state authorities I refer to include numerous Moroccan institutional and bureaucratic actors; however, among this group the most important are the king and the Ministry of Habous and Islamic Affairs (hereafter MHAI, or religious affairs ministry).35

The king, considered a sharif, or descendent of the Prophet Mohammed, is recognized by Article 41 of the constitution as the “Commander of the Faithful” who “ensures respect for Islam,” the “guarantor of the free exercise of beliefs,” and the top religious authority who “presides the High Council of cUlamāʾ.”36 The term “Commander of the Faithful” (in Arabic, amīr al-muʾminīn) is particularly revealing of the ambiguity between the national and the transnational in the Moroccan religious field: the term lays a claim to being the supreme religious and political leader of the Muslim community (or umma), which transcends state boundaries; however, the king’s religious authority is not meant to apply to the whole of the Muslim world, but rather to the Moroccan national umma.37

The king also represents the central figure of political and executive authority in Morocco, while his court and the state apparatus at his disposal is referred to using the historical term ‘makhzen.’38 For decades the direct influence of the makhzen within the democratically elected government was represented by the so-called ‘sovereign ministries’ (ministères de souveraineté), which were led by individuals designated directly by the king. The numerous political and constitutional reforms that have been enacted since King Mohammed VI came to power in 1999 have substantially decreased the number of these sovereign ministries; however, there are two that have not, and most likely will not, change within the current political system: national defense and religious affairs.

The king personally launched the reform of the religious field during a speech in front of the country’s Islamic scholars on 30 April 2004, and followed up with a second set of reforms in 2008. The catalyst for these reforms was a series of suicide bombings that struck Casablanca in 2003, the worst terrorist attack in the country’s history. The attack shocked the country, even more so when it was revealed that it had not been carried out by foreigners, but rather Moroccan Salafi Jihadists from poor neighborhoods in Casablanca. Up until that point, Morocco had regularly touted its “exceptional status” (l’exception marocaine) with regard to Islamic radicalism both at home and abroad. Indeed, relatively speaking the Moroccan state has been quite successful in checking violent groups and coopting more mainstream Islamist opposition movements, such as the Justice and Development Party (Parti de la justice et du développement, PJD), or containing others, such as al-cAdl wa-l-Iḥsān.39 However, after the 2003 bombings, this exceptional status was severely called into question.

A significant change had already occurred in 2002 when Ahmed Toufiq, a well-known writer, professor, and member of the Sufi Qādiriyya Boutchichiyya brotherhood (ṭarīqa), was appointed as the new Minister of Habous and Islamic Affairs. His predecessor, Abdelkebir Alaoui M’daghri, had been “known for his more accommodating views towards Wahabism [sic]” and toleration of Saudi-trained imams during his twenty years as minister, a stark contrast to the academic and Sufi leader Toufiq, who had been “demanding more state control of religious public affairs.”40 Toufiq’s appointment would be given center stage following the bombings, increasingly seen as part of a series of moves designed to ward off radicalization alongside a new anti-terrorism law passed in 2003, enhanced police surveillance of radical groups and clerics, and attempts to address the socioeconomic roots of the Casablanca attacks by razing slums and constructing publicly-funded housing projects.

Since 2004, the scope of these reforms has been impressive. The state has moved to reassert its control over the religious field at all levels, starting with the creation of new departments within the religious affairs ministry to ensure greater control over mosques and religious education. The latter has attracted special attention, as religious curricula have been revised while Islamic institutions of higher learning have been restructured and brought under the purview of the ministry. Furthermore, the same year the reforms were launched, the position of female preacher (murshidāt, or “guide”) was officially institutionalized. This last measure was portrayed in media sources as a veritable “revolution,” given that Morocco is now one of the only Muslim countries in the world to have an official program that confers religious authority on women in the public sphere.41

With the creation of the Mohammed VI Foundation for the Publication of the Holy Qurʾan in 2010, the state established a monopoly over Qurʾan distribution and publication in Morocco with goal of eliminating imported foreign copies that did not correspond to the Mālikī rite and the warsh-style of calligraphy and recitation used in Morocco.42 Modern technologies were also mobilized, leading to the creation of an Islamic radio station in 2004 (which has remained one of the top radio stations in the country ever since), an Islamic television channel in 2005, and a website for the MHAI in 2005.43 Overall, the reforms have led the state to become more directly involved in all religious domains and preaching activities, religious education, fatwa-issuing, and religious publications have all come under greater state supervision.

Moreover, the Moroccan state has increasingly moved towards a system in which imams and religious personnel are treated as public employees, a well-known configuration in Muslim countries which had once been part of the Ottoman Empire, such as Turkey and Algeria, but which had never been a distinctive feature of relations between the state and religion in Morocco before. In 2008, the king announced the establishment of the “culamāʾ pact” (Mithaq al-culamāʾ), a special program focused on improving the conditions and training of Morocco’s approximately 46,000 imams, and two years later he founded the Mohammed VI Foundation for the Welfare and Education of Imams.44 Even more to the point, the MHAI issued a decree in March 2006 setting out the necessary requirements to be appointed as an imam in a mosque, while a further decree three months later established the model contract that would be used to recruit religious personnel (imams, murshidūn, and murshidāt). The decree also specified that the contract may be ruptured without any benefits if the local council of culamāʾ finds that a member of the religious personnel has not been following the Mālikī rite and the Ashcari doctrine.45

Indeed, despite the fact that the suicide bombers were Moroccan, the fact that they were inspired by Saudi Wahhabi Salafism and tied to transnational jihadist movements emerged as the central explanatory factors for the attacks. As a result, many of the subsequent reforms focused on reasserting Morocco’s specific national spiritual heritage: first and foremost the Mālikī school of Islamic jurisprudence (madhhab), the Ash cari creed (caqīda) and Sufism. As the king stated in his 2004 speech announcing the restructuring of the religious field, the Sunni Mālikī rite is the “unique historical reference … upon which the unanimity of the nation has been built,” and that “my attachment to doctrinal unity at the religious level is similar to my constitutional commitment to defend the territorial integrity and the national unity of the homeland.”46 As Akdim observes, this has led the state to “develop a veritable doctrine of religious sovereignty” in which the expression “spiritual security (amn rūḥī)” shows the extent to which the spiritual domain is included in the logic of state security.47

In and of itself, the dangers associated with ‘foreign Islam’ do not constitute a new theme: for instance, in the preamble to the royal decree that founded the High Council of cUlamāʾ (al-Majlis al- cAlamī al-Aclā) in 1981, “the dangers of foreign ideologies” to the “identity of the Moroccan nation and its authentic values” are expressly mentioned, indirectly alluding to the spread of Shi cism following the Iranian revolution of 1979.48 The current reforms likewise characterize Islamic currents not endorsed by the state as both foreign and dangerous, and in particular have focused on countering the rise of Saudi Wahhabi Salafist ideas in the Moroccan religious field.

Salafism in general is characterized by the desire to return to the ways of the first three generations of Islamic “righteous ancestors” (al-salaf al-ṣāliḥ), and a rejection of all forms of tradition or authority that do not adhere to a strict literalist interpretation of the Qurʾan and the sunna (the sayings and actions of the prophet Muhammed). Since the eighteenth century, there have been various currents of Salafism in Morocco, some of which have been more amenable to the monarchy, while others, such as the current wave of Wahhabi Salafism, may reject the legitimacy of the Moroccan king as a religious authority.49 Consequently, the religious authorities of the Moroccan state have decided to combat this foreign current of Salafism by turning to a triumvirate of national religious traditions: Malikism, Ashcarism, and Sufism.

The Mālikī rite (madhhab), based on the teaching of Malik ibn Anas (711–795), is one of the four main schools of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), and is followed in North and West Africa, as well as in a number of Arab states of the Persian Gulf. As a member of the religious affairs minister’s cabinet explained to me, “there can be disagreements depending on history concerning political affairs or [prerogatives], but dogmatically no. [Morocco] has always been Mālikī. There is a rite to respect, there is a tradition to respect.”50 Aside from the importance of the Mālikī school as a national tradition in Morocco, religious authorities also claim that it represents a more tolerant form of Islam better suited to adaptation, and point to the historical examples of al-Andalus and Morocco’s mixed Arab and Amazigh populations. Indeed, compared with other schools, the Mālikī school gives greater importance to the concept of maṣlaḥa (“public interest”) in questions of Islamic jurisprudence, thus opening the door to greater flexibility based on local community practices.51

Ashcarism refers to one of the principle schools of Sunni theology (cilm al-kalām), founded by Abu al-Hasan al-Ashcari (873–935), and is particularly associated with the Mālikī and Shaficī schools of jurisprudence. It arose at a time when a current of Islamic scholars called the Muctazilites had become particularly well versed in using the language of Aristotelian philosophy and argued that reason alone could suffice in order to understand religious truths in Islam. The position of the Muctazilites provoked intense opposition from the Athariyya creedal school, which believed that human reasoning “can neither be trusted nor relied upon in matters of religion, thus making theology a sinful and dangerous exercise in human arrogance.”52 Ashcarism similarly opposed a number of Muctazilite ideas and tried to strike a middle ground between them and the Atharis, which led to the generalization of a historical narrative viewing Ashcarism as a conservative, literalist movement. However, as argued by Halverson, Ashcarism holds the potential for a renewal of Islamic thought due to the great relevance of rationalism and reason to its understanding of faith, which is in direct opposition to the “strict adherence to the literal outward (zahir) meanings of the sacred texts,” as promoted by their modern Athari adversaries: the Wahhabi and Salafi movements.53 Ashcarism can thus be used by Morocco to “buttress its counterterror policy” by affirming its “moderate approach that values human reason.”54

Finally, Sufism has a deep-rooted history in Moroccan politics and in popular religious practice and has attracted an important degree of scholarly attention.55 However, as is the case throughout the Muslim world, it has been one of the main targets for Salafis, especially those inspired by the Saudi Wahhabi current, who accuse it of corrupting Islam through beliefs and practices it considers as heretical innovations (bidca). Consequently, the decision to promote Sufi movements like the boutchichiyya and appoint its members to positions of power (such as minister of Islamic affairs) show that “the state is making every effort to play the Sufi card effectively to protect itself from extremism and to retain its power,” echoing similar strategies favored by certain Middle Eastern governments and US policy analysts.56

This section has showed that since the 2003 Casablanca bombing, the king, and by extension the Moroccan state, have claimed the responsibility to supervise and defend the spiritual boundaries of the nation, just as much as the territorial boundaries of the state. However, as mentioned earlier, the spiritual boundaries of the Moroccan religious field are transnational, and include millions of Moroccans living in dozens of foreign states. The following pages will provide an analysis of how the Moroccan state has extended its reforms of the religious field at home to its diaspora communities abroad.

THE NEW REFORMS ABROAD: FROM DOMESTIC SECURITY CONCERNS TO DIASPORA POLITICS

The extension of these reforms to Moroccan communities abroad demonstrates an understanding of the transnational religious field as both an opportunity and a threat. The emphasis on Moroccan Islam as distinctive of both Moroccan identity and religious practice aims to carve out a national space within a religious field that is characterized by its capacity to surpass state boundaries. During my interview with one leader of a prominent Moroccan religious association in Belgium, this vision was expressed very clearly:

The organization of the religious field passes necessarily through Europe. If the religious field is disorganized in Europe, that can have grave consequences for Morocco. It destabilizes the Moroccan model of . . . religiosity. So that’s why we try to anticipate, it’s about prevention. So that there’s a direct connection between Morocco, the interior and the exterior, concerning the model of religiosity: the Mālikī school, the Ashcari doctrine . . . because otherwise the whole structure of society will be destabilized.57

As mentioned, national security interests represent an important element that motivates this religious public policy. Nevertheless, recent developments have gone far beyond the limited scope of security interests, which better characterize Morocco’s relationship with its citizens abroad during the authoritarian années de plomb of King Hassan II.58 The diaspora policies that the Moroccan state has increasingly employed do not neglect economic or security issues, but go beyond them with the goal of reinforcing ties with the home country and establishing permanent networks of influence in the countries in which Moroccans have settled, recognizing the fluidity with which ideas and people move between states within the religious field. Equally important to facilitating this new vision have been the reforms made to the Nationality Law in 2007, which now automatically grants nationality to children of both Moroccan men and women, regardless of place of birth; before the reforms only Moroccan men could pass on their nationality to their children.59

Islam, seen as an integral element of Moroccan identity, continues to play a central role in this broader vision of diaspora politics, in which the provision of religious services abroad is construed as part of diaspora citizenship. Both sending religious personnel abroad and providing financial support constitute central policy instruments for Morocco’s transnational governance of Islam. The following sections will explore both of these strategies in more detail.

RELIGIOUS PERSONNEL

Religious personnel are primarily sent abroad for the month of Ramadan, an initiative that concerns the FHII, the MHAI, and the foreign affairs ministry. Moroccan financial support for imams who are permanently based in foreign countries or who stay abroad for extended periods of time has been much less the norm. The FHII at one time provided funding for upwards of twenty-one “permanent” imams across Western Europe; however, by 2008 this had dropped to only seven, five of whom were in France; one in Spain, and one in the United Kingdom.61 At the same time, 2008 was the same year when for the first time the MHAI sent a contingent of thirty imams to France for a four-year period, an initiative which I will discuss in greater detail below.

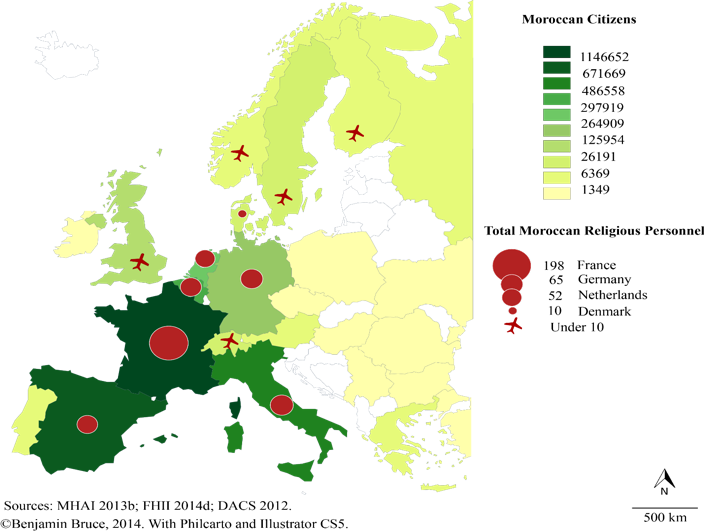

As shown in Figure 1 (see above), the number of religious personnel sent abroad generally reflects the size of the Moroccan community in each country. There are exceptions to this rule: for instance, the number of Moroccans in Germany in 2012 was smaller than in every other of the main six countries; however, the number of religious personnel that it received was larger than every country other than France. This discrepancy may be the result of the rapid changes in Moroccan migratory flows over the last decades and the fact that Moroccans have had a longer presence in Germany: the bilateral labor agreement between both countries was signed in 1963, and up until the mid-1990s there were more Moroccans in Germany than in Spain.

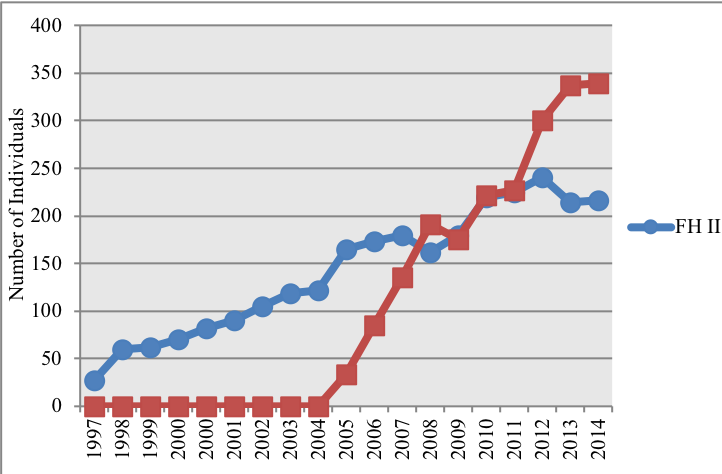

In general, the delegations sent abroad by the MHAI are primarily composed of Qurʾan reciters for the evening tarāwīḥ prayers during Ramadan, while the number of male and female preachers is much smaller. The total size of the delegations has gradually risen over the years, from approximately 200 in 2008, when the first graduates of the program for female preachers were sent abroad, to almost 350 in 2013. Besides this gradual rise in numbers, the most striking change has been the increasing involvement of the MHAI, whose contingent of religious personnel for Ramadan since 2008 has grown to equal or surpass that of the FHII (see Figure 2 below).

The selection of the religious personnel is the responsibility of another level of religious administration: the High Council of cUlamāʾ and the regional culamāʾ councils. During an interview with the religious affairs ministry official responsible for Moroccans residing abroad, I was told that neither the MHAI nor the FHII carry out any examinations of the religious personnel to be sent abroad; rather, this is a task incumbent on the culamāʾ councils and occurs during the selection process, which begins with a call for applications.63 According to another member of the MHAI with whom I spoke, who was in charge of preparing the delegations to be sent abroad, the culamāʾ councils “demand minimal standards” of the religious officials, such as good knowledge of Islamic sciences and basic linguistic knowledge of the countries they are to be sent to. However, above all they require that the imams and preachers follow “the right path” (la bonne voie): “there can’t be any extremism; it can’t be someone who’ll say ‘don’t eat French meat’ or ‘don’t speak French.’”64 The interviews carried out with ministry officials confirmed a distinct sensitivity towards the perception of the religious personnel abroad, especially by foreign state officials, in order to avoid any potential diplomatic incidents that would undermine the Moroccan state’s reputation as a solid mainstay of ‘moderate Islam.’

The streamlined nature of the procedure is what enables different stages of control to be applied by the Moroccan state. Not only is the religious personnel sent by the FHII subject to oversight ahead of time at the religious level of the culamāʾ councils and the MHAI, but once the list of religious personnel is established, it is also transmitted to both the interior and foreign affairs ministries.65 This ensures that a second round of centralized political and administrative control occurs later on, giving state authorities the ability to remove individuals considered sympathetic to radical groups or Islamist movements, such as al- cAdl wal-Iḥsān or the PJD. For instance, according to Jaabouk, forty-five imams were removed from the Ramadan delegation in 2013 after they received a letter from the interior ministry stating that “the nation has need of your services”—but not abroad. Jaabouk’s article draws a direct link between the intervention of the interior ministry and the religious affairs ministry’s recent policy of “targeting religious personnel who support the MUR [the “Unity and Reform Movement,” tied to the PJD network], the PJD, or al- cAdl wa-l-Iḥsān.”66 Indeed, this assertion seems supported by the MHAI’s suspension of five imams for having prayed for Sheikh Abdessalam Yassine (the founder of al- cAdl wa-l-Iḥsān) in their sermons a few days after the Yassine’s death in February 2013.67

Considering that the image and reputation of the Moroccan state is at stake with each delegation, authorities are careful that the religious personnel sent abroad abides by certain rules. These rules are explicitly set out by the MHAI, as one ministry official explained to me:

The preachers we send, we have them sign a kind of document where they commit themselves to scrupulously respecting the task that they have been assigned, namely preaching. And to respect the laws of the country, and to not interfere in the affairs of the country. You’re there for a specific task, you will accomplish it and come back, period.68

The document mentioned by the ministry official comes in addition to the rules laid out in the ministry’s “Guide for the Imam,” which states that imams must avoid speaking of “personal, political, or media conflicts while giving a sermon,” and that this would be “an unforgivable error.”69 The state’s position on this matter has been made even stricter with a new decree promulgated in July 2014, which formally forbids imams from being members of political parties and unions.70 Moreover, in order to ensure smooth relations with receiving state authorities during the visa application process for the imams, the corresponding consular sections are provided with an official mandate issued by the Moroccan state for each individual sent abroad, in addition to the regular documentation. While the practice of sending religious personnel abroad has attracted criticism from politicians and state officials in the cases of Spain and the Netherlands, the striking overall tendency is that of steadfast international cooperation.71

The procedures concerning the sending of religious personnel have been devised to create a political and administrative framework through which the Moroccan state can determine the content of the “religious goods” that its employees provide in the religious field abroad. In addition to these policies, the Moroccan state also cooperates with and assists particular religious actors based in foreign countries, mainly by means of direct financial support. The next section will explore how providing funding is similarly designed to co-opt and maintain control over the designated representatives of Moroccan Islam, and thereby reinforce the position of the state as the main religious authority for the diaspora.

MUSLIM RELIGIOUS ASSOCIATIONS AND FUNDING

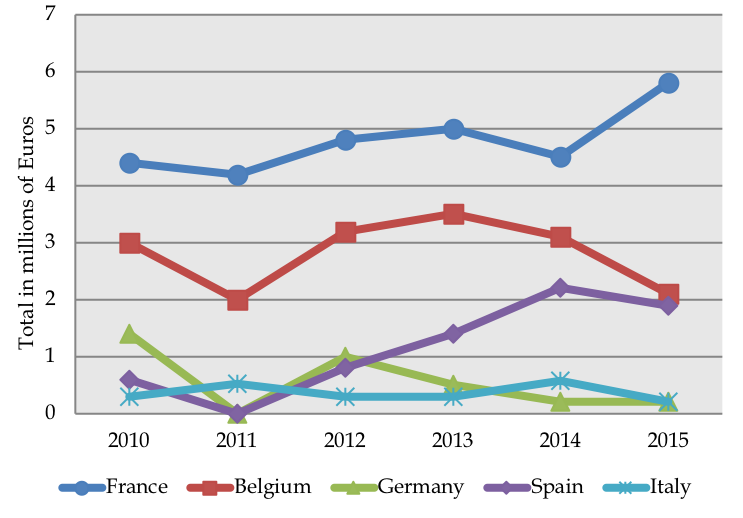

Direct funding represents one of the most important instruments by which Morocco is involved in shaping the religious field outside of its borders. The financial support from the makhzen can sometimes come from the king himself, such as for the construction of mosques in the French cities of Saint-Étienne and Blois, but in general it is institutionalized at the level of the religious affairs ministry: over the last few years the MHAI has provided approximately eleven million euros in annual funding for mosques and religious associations across Western Europe (see Figure 3 below).

Indeed, this home state involvement represents a central factor in understanding specific evolutions that have occurred regarding Moroccan Islam in the religious fields of different Western European countries. In order to demonstrate this point more thoroughly, I will return to the case of France, where the main Moroccan Islamic associations have undergone a series of mutations over the past thirty years that demonstrate the persistent and pervasive influence of home- state diaspora politics.

As depicted in the figure above, France is currently (and has historically been) the top recipient for Moroccan state funding directed towards religious associations. Indeed, Moroccans run the majority of Muslim mosques and prayer spaces in France, and though many of these associations remain autonomous, “people of Moroccan origin and nationality continue, against all expectations, a kind of national Islam which transcends currents.”73 As a result, the Moroccan state has been able to utilize this attachment to a national Moroccan Islam to its advantage and exert influence over a variety of local Islamic associations, despite the important ideological differences that exist between them. At different moments this influence has extended to the National Federation of French Muslims (Fédération Nationale des Musulmans de France, FNMF), a ‘big tent’ federation that originally represented many different currents and nationalities; the Union of Islamic Organizations of France (Union des Organisations Islamiques de France, UOIF), close to the Muslim Brotherhood and usually hostile to the activities of home states in France; and the Tabligh, a non-political Sunni proselytizing movement originally founded in India, but which has a large following among Muslims of Moroccan origin in France. As Dumont points out in his thesis on French Moroccan associations, it is a relatively frequent phenomenon that the Moroccan state or other Moroccan political actors intervene and co-opt community-oriented associations, leading to their gradual reorientation towards a more nationalistic stance,74 and financial support is one of the most effective means by which to do so.

During the 1990s, changes in the leadership of the ‘big tent’ FNMF gradually led to it becoming the main representative of Moroccan Islam, even though it had been originally founded to bring together numerous groups opposed to the dominance of Algerian Islamic associations in the French Muslim field. When the French Council of the Muslim Faith (Conseil français du culte musulman, CFCM), a representative national body for Muslims, was created in 2003, the FNMF won the first elections thanks to an effective campaign supported by the Moroccan consulates. The goal of the council was originally to serve as a means of providing the state with recognized interlocutors, somewhat similar to the corporate system used for Protestant and Jewish leaders. However, it has been beset by numerous crises since its creation. In part, this has been due to competing interests between foreign states such as Morocco and Algeria, but also Turkey, for whom winning the elections is a matter of national pride. Primarily though, the CFCM’s problems have been due to the widespread disaffection of French Muslims who view the council as an artificial top-down construct with very little impact on the ground.75

In a similar vein, despite its electoral victory, the FNMF had never been a fully functional organization; frequently characterized as an “empty shell” (coquille vide) by its detractors, it began coming apart at the seams in 2005 due to internal infighting.76 Its place as the semi-official representative of Moroccan Islam was taken over by the Rally of French Muslims (Rassemblement des Musulmans de France, hereafter “the Rally”), founded in 2006, which won all CFCM elections thereafter, and at its height counted upwards of 550 affiliated mosque associations.77 Nevertheless, by 2012 the Moroccan state had once again decided to restructure its partnerships abroad, and the Rally found itself eclipsed by the newly-formed Union of French Mosques (Union des Mosquées Françaises, hereafter “the Union’), under the presidency of a former Rally leader. Indeed, the impact of diaspora politics is at its most evident in the case of these three organizations (the FNMF, the Rally, and the Union), as there is nothing in the local French Muslim field that can account for their individual rise or fall if one fails to take into account the influence of Moroccan transnational religious governance.

Following the decline of the FNMF, the success of the Rally was directly tied to the new policies that had arisen as part of the Moroccan state’s reform of the religious field. Since its foundation, the Rally was made responsible for the orientation and organization of imams sent from Morocco during the month of Ramadan, a task that in the past had been fully monopolized by the foreign affairs ministry and the Moroccan consulates abroad.78 Moreover, in 2008, the MHAI reached a joint agreement with French authorities in order to send a contingent of thirty imams for a four-year period. This was the first time that Morocco had sent such a large group of religious personnel abroad for such a long period of time—though it followed the same modus operandi employed by other states, such Algeria and Turkey, which have been sending state-employed imams for three to five-year periods to serve their communities abroad for decades.79 As with the Ramadan imams, the Rally was the receiving partner for this contingent of religious personnel and received over four million euros in direct funding from the MHAI to pay their salaries.80 In this fashion, between 2006 and 2012, the Moroccan state structured and channelled its religious diaspora policies through the Rally in France, paralleling the ongoing centralization of transnational religious activities within the MHAI in Morocco itself.

Despite, or perhaps thanks to, this move towards a more solid organizational structure, the subsequent shift from the Rally to the Union was both rapid and systematic. The annual Ramadan imams were channelled towards Union relays instead of Rally ones, as the former association quickly replaced the latter as the official partner of the religious affairs ministry and Moroccan state officials. An analysis of the associations section of the official French governmental journal (Journal Officiel) that I carried out from the beginning of October to the end of December 2013 highlights the remarkably coordinated fashion by which at least eleven Union regional associations were founded across the country. Moreover, a look at the addresses given by the Union’s regional branches reflects well the historical evolution of the Moroccan Muslim field in France: for instance, the Union branch in the region of Midi-Pyrénées replaced the Rally regional association located at the same location, and the Union branch in the Nord region is situated precisely where the Moroccan amicale for the Nord region had been located. These ties are clear evidence of the connections between the amicales, the Rally (for a time), and now the Union.81

As mentioned, the main reason for the decline of the Rally and the rise of the Union is tied to political developments in Morocco unrelated to local dynamics in France. According to interviews I carried out with officials from the French interior and foreign affairs ministries, Moroccan authorities had begun worrying that the Rally leadership was becoming too close to the PJD, the Islamist political party that had recently come to power following the 2011 parliamentary elections in Morocco. Consequently, these French officials had been contacted by their Moroccan counterparts to inform them that they were reorienting their activities towards the newly founded Union instead of the Rally.82 Despite the fact that the Rally president denied this explanation in a separate interview, since 2014 his association no longer receives funding from the Moroccan religious affairs ministry.83

At the local level, the influence of home state funding for religious activities can have a more visible impact than the byzantine politics of the Muslim federations at the national level might suggest. For instance, the Bilal mosque in the Parisian suburb of Clichy-Sous-Bois has had an imam sent from the religious affairs ministry since 2008. The mosque is one of the largest in the Parisian banlieue and has a high degree of symbolic importance, given that it was at the center of the 2005 riots that spread across the country and attracted an immense degree of international media attention. The president of the mosque association served as Rally president of the Île-de-France–Centre region between 2011 and 2013 (and as municipal counsellor for the main center-right political party); however, the conflict between the national federations seemed to interest him little when I visited the mosque in 2014.

According to the mosque president, the only noticeable impact of the MHAI’s decision to change its partnership from the Rally to the Union involved the payment of the imam’s salary.84 Financial considerations had figured greatly in the Bilal mosque’s request for an imam paid by the religious affairs ministry, and their former imam was quietly dismissed when the possibility to receive a home state-paid one arose in 2008. Other than the issue of who would pay the imam’s salary, the transition from the Rally to the Union had no effect on the local attendance, the mosque association leadership, or the imam himself, whose fundamental connection was with the MHAI. In other words, the most significant change at the Bilal mosque (i.e. the arrival of a new imam) came about as a result of a new religious diaspora policy, while the dispute between associations proved to be merely a peripheral question of logistics.

Following the same goal of centralizing and expanding religious activities abroad, in 2008 King Mohammed VI founded the European Council of Moroccan cUlamāʾ (hereafter CEOM) by royal decree, with the goal of “assuring the correct observance of religious obligations and Islamic worship and the preservation of its precepts for all Moroccans, men and women, living in Europe, within a framework of tranquility and spiritual security according to the Ash cari doctrine and the Mālikī rite.”85 The CEOM, based in Brussels, has since organized a number of conferences across Europe where it brings together Moroccan Muslim leaders based in Western European countries, rendered possible largely thanks to the MHAI funding of two to three million euros provided per year.86 Similar activities have been undertaken by the working group on religion and religious education of the Council of the Moroccan Community Abroad (CCME), founded by the king in 2007, which has organized three international conferences on the subject of Islam in Europe since its creation.87 Finally, only one year after its inauguration, the Mohammed VI Foundation for the Publication of the Holy Qurʾan had already undertaken the mission of sending 25,000 Moroccan-style Qurʾan to Moroccan Muslim communities in Western Europe.88 All of these recent initiatives are evidence of how Morocco has made use of financial support as a diaspora policy instrument in order to have an impact on the development of Moroccan Islam in Western Europe.

TUMULTUOUS GEOPOLITICS AND MOROCCAN SOLUTIONS

In the wake of the uprisings that have swept the Arab world since 2010, Morocco has sought to maintain its position as a beacon of stability. The geopolitical consequences of the rise of Islamist groups in Mali, Libya, and the Islamic State (IS) in Syria and Iraq, have further contributed to this stance, along with the fact that IS-sponsored terrorist attacks in France and Belgium have involved individuals of Moroccan background, as was the case with the Madrid bombings in 2004.

Morocco experienced a series of protests in 2011, known as the “February 20th Movement,” which led to constitutional reform in July and the electoral victory of the PJD in November of the same year. Nevertheless, while the demonstrations and the activist mobilization did leave its mark on a wide spectrum of Moroccan society, the monarchy managed to take advantage of the situation to both reinforce its position within the Moroccan state and push through reforms that it had already been preparing.89 In the religious field, the same year gave rise to a phenomenon heretofore never seen in the country: protests by imams in front of the parliament in Rabat. The main reason for these protests on the whole was the low salaries and sparse benefits received by religious personnel; however, they were also due to the fact that the religious affairs ministry had forbidden imams from becoming involved in political issues while also obliging them to support the new constitution and “vilify the February 20 Movement.”90

Faced with these demands, the strategy of the MHAI has been to continue its ongoing focus on the (re)training of imams as part of the culamāʾpact initiative, a fundamental feature of the religious field reforms announced in 2008. However, the training of imams has proved to be a policy tool for more than just national considerations: during King Mohammed VI’s visit to Mali in November 2013, just one year after the conflicts that had engulfed the north of the country, an agreement was signed with President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta to train 500 Malian imams in Morocco. Over the following months, Morocco received requests from other Sub-Saharan states (with which it shares the Mālikī school of Islamic jurisprudence) to train their religious personnel as well.

In order to effectively develop these local and international programs, on 27 March 2015, the Mohammed VI Institute for the Training of Imams was officially opened in Rabat. The institute is located in the university district of Irfane, down the road from the Mohammed VI Foundation for the Welfare and Education of Imams, and is tied to the famous Al-Qarawiyyin University. The director is Abdeslam Lazaar, who led the training program for the Malian imams, while professors include high-level members of the MHAI such as Abdellatif Begdaoui Achkari, head of Minister Toufiq’s cabinet. The institute comprises a mosque, modern and well-equipped classrooms, a library, computer rooms, as well as sports and recreation facilities alongside a dormitory with enough space to house 700 students.91

In September 2015, a few months following the inauguration of the institute, French President François Hollande visited Morocco and the two states signed a cooperation agreement whereby French citizens would be similarly included in the imam training programs. The organization of the program in France is carried out by the Union and its regional branches, and offers both a two-year “basic training” (formation initiale) program as well as a three-month “continuing education” (formation continue) program, which is designed for individuals who already work as imams and Muslim chaplains. A flyer on the Union’s website explains these details along with the modalities for applying and the fact that each student admitted benefits from a monthly scholarship of two hundred euros as well as free room and board.92

Though currently one of the smallest national groups represented at the institute, the number of French students is growing and was deemed important enough to receive a visit from a special French senate committee tasked with conducting an in-depth review of Islam in the country. In a news broadcast on the visit the senators seemed positively impressed by the imams, and one member of the delegation, André Reichardt, even went so far as to exclaim “if there were many more students who wished to become imams in the world and who sounded like him [a student of the program], I think our problems would be resolved, voilà!” This appraisal was echoed by Jean-Pierre Filiu, a well-known French scholar of the Middle East, who was invited to give a talk on the topic of global jihad a few months later at the institute, and who wrote that the students “are intent on combatting jihadist propaganda” and that “this ‘French’ cohort is motivated and determined.”93 At the same time, Filiu’s use of quotation marks when describing the group as French highlights the ambiguity of their binational belonging—presumably the ‘Frenchness’ of their Moroccan Islam as well.

In their final briefing, the senatorial delegation mentions their positive impressions from the visit to the institute, but also echo a high-level bureaucrat of the interior ministry who pointed out that another advantage of the “consular” imams is that “other than being paid by the state of origin, they are also controlled by these states and none of these imams are a source of radicalization.”94 Indeed, still reeling from the terrorist attacks in Paris in January and November 2015, and Nice in July 2016, French authorities have struggled to find new ways to address the issue of Islamic religious governance within the country due to electoral worries over a growing far-right and the legal hurdles posed by the Law of 1905 on state secularism (laïcité). Instead, the current strategy repeats a decades-old practice of cooperating with foreign state authorities such as Morocco (along with Algeria and Turkey) who have the capacity to intervene directly in the religious field and thereby indirectly attempt to control the development of Islam in the country.95

THE CONSEQUENCES OF MOROCCAN RELIGIOUS DIASPORA POLICIES ABROAD

This article began by asking why Morocco has given such weight to Moroccan communities abroad as part of the state’s official restructuring of the religious field, and how studies on diaspora politics can help in explaining this approach. As I have argued in this paper, the extension of Moroccan religious policies to the diaspora communities abroad reflects an understanding of the religious field as a transnational social field in which ideas and individuals circulate in ways that can escape the control of state institutions. Consequently, and as part of its strategy to retain control of the religious field at home, the state must be equally implicated in governing Moroccan religious activities and organizations in the diaspora.

Furthermore, as has been highlighted by other scholars of diaspora policies, the last decades have seen the rise of a new perception by home states that communities abroad constitute potential assets, and are composed of individuals with rights and necessities that the home state ought to respect. In this sense, providing religious services to Moroccan Muslims abroad can be portrayed as an obligation of the state, especially when the ruler of the state is constitutionally designated as the principal religious and political authority in the country.

For a state seeking to maintain a close relationship with a diaspora that continues to associate national identity with religion, the decision to focus on Islam and religious activities is also a sound strategy: as Brouard and Tiberj have highlighted in their survey of “new French,” “those of Moroccan origin describe themselves a little more often as Muslims” when compared with immigrants from other backgrounds, and they are among those who most frequently respond that they feel close to their country of origin.96 Similarly, a study commissioned in 2010 by the Council of the Moroccan Community Abroad, comprised of young first- and second-generation Moroccans in six Western European countries, showed that a large majority maintained strong connections to their country of origin, and approximately half regularly practiced their religion.97

The focus of this paper has been on analyzing the motivations and interests of a specific state with regard to its diaspora; however, it is equally important to ask whether its strategies are truly effective? The aforementioned survey on Moroccan diaspora youth reveals that only nine percent are members of a religious association, and there is no guarantee that those listening to an official home state imam or receiving funding from the religious affairs ministry will act exactly as the government hopes they will. Moreover, the strategy of emphasizing traditional components of Moroccan Islam, such as the Mālikī rite and the orthodox Ash cari creed, will not automatically attract young Muslims of Moroccan background. As Belhaj points out, the appeal of the radical Salafi discourse that comes from Saudi Arabia for European Muslim youths is that it is the only one that “escapes from the control of Arab regimes and corresponds to their ‘radical’ social conceptions,” whereas the traditional Islam of their parents does not speak to their lived social realities.98 Finally, the assumption that promoting Sufism can counteract the spread of Salafism is by no means proven; indeed, it seems that Morocco may now be reconsidering its own strategy of exclusion and moving towards co-opting certain Salafist elements hoping “to engage in an open dialogue with Salafi youth and provide them this ‘correct’ understanding of Salafism.”99

All these issues raise valid doubts concerning the efficacy of Morocco’s religious diaspora policies; however, this paper does not contend that home states are able (or seek) to fully control their diaspora communities. Rather, as mentioned in the introduction, my goal has been to show how states and their policies “shape the options” for migrants in a transnational religious field. This strategy begins with maintaining good relations with the governments of the Western European countries, which enables the implementation of religious diaspora policies in foreign countries in the first place. Thereafter, it can have significant effects on provoking the rise and fall of Moroccan Islamic associations in France, the replacement of the imam at the Bilal mosque, or the enrolment of Franco-Moroccan students at imam training institutes in Morocco. The influence of home states over transnational religious fields is thus not an issue of outright control, but instead a more diffuse effort aimed at preventing the emergence of independent forms of local religious authority that could threaten the established order back home. Indeed, whether at home or abroad, the Moroccan state’s most potent strategy is its ability to co-opt those who oppose it, all the while reinforcing the same structures of legitimacy that underpin the authority of the current regime.

NOTES

My thanks to Laurie Brand, Tamirace Fakhoury, and the two anonymous peer reviewers of this article for their astute and candid observations, as well as to Marilyn McHugh Drath, managing editor, and Sarah Mink, copy editor, of Mashriq & Mahjar for their continued support and close and attentive reading of the text.↩︎

Ministère chargé des Marocains résidant à l’étranger et des affaires de la migration, Guide Des Marocains Résidant À L’étranger. Édition 2015 (Royaume du Maroc, 2015); World Bank Group, Migration and Remittances. Recent Developments and Outlook, Migration and Development Brief 26 (Washington DC: The World Bank, 2016), http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/788241468180260116/Migration-and-remittances-recent-developments-and-outlook.↩︎

Roger Waldinger and David Fitzgerald, “Transnationalism in Question,” American Journal of Sociology 109, no. 5 (2004): 1177.↩︎

Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye, “Transgovernmental Relations and International Organizations,” World Politics 27, no. 1 (1974): 39–62; Saskia Sassen, The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991); Linda G. Basch, Nina Glick Schiller, and Cristina Szanton-Blanc, Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States (London: Gordon and Breach, 1994).↩︎

Yossi Shain, “Ethnic Diasporas and U.S. Foreign Policy,” Political Science Quarterly 109, no. 5 (1994): 811–41; Steven Vertovec and Robin Cohen, Migrations, Diasporas, and Transnationalism (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1999); Gabriel Sheffer, Diaspora Politics: At Home Abroad (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003); Ato Quayson and Girish Daswani, eds., A Companion to Diaspora and Transnationalism (New York: Blackwell, 2013).↩︎

Stéphane Dufoix, Carine Guerassimoff, and Anne de Tinguy, eds., Loin des yeux, près du coeur: Les états et leurs expatriés (Paris: Sciences Po les Presses, 2010).↩︎

Félice Dassetto and Albert Bastenier, L’islam transplanté: vie et organisation des minorités musulmanes de Belgique (Brussels: EPO, 1984); Félice Dassetto, “L'Islam transplanté : bilan des recherches européennes,” Revue européenne de migrations internationales 10, no. 2 (1994): 201–11; Marcel Maussen, The Governance of Islam in Western Europe: A State of the Art Report, Working Paper 16 (Rotterdam : IMISCOE, 2007), http://www.euro-islam.info/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/governance_of_islam.pdf.↩︎

Yasemin Nuhoğlu Soysal, Limits of Citizenship: Migrants and Postnational Membership in Europe (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994), 17–22.↩︎

Laurie A. Brand, States and Their Expatriates: Explaining the Development of Tunisian and Moroccan Emigration-Related Institutions, Working Paper No. 52 (San Diego: Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, 2002), 8, https://ccis.ucsd.edu/_files/wp52.pdf.↩︎

Hein de Haas, Between Courting and Controlling: The Moroccan State and ‘Its’ Emigrants, Working Paper 54 (Oxford: University of Oxford, COMPAS, 2007), 8–20.↩︎

Laurie A. Brand, Citizens Abroad: Emigration and the State in the Middle East and North Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2006), 70–71.↩︎

Gilles Kepel, Les banlieues de l’islam: Naissance d’une religion en France (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1991), 283.↩︎

Kepel, Les banlieues de l’islam, 142–3.↩︎

Solenne Jouanneau, Les imams en France: une autorité religieuse sous contrôle (Marseille: Agone, 2013). These programs still exist and are called “Country of Origin Language and Culture Courses” (Enseignements de langue et culture d’origine or ELCO).↩︎

On the rise in the number of religious associations, see Kepel, Les banlieues de l’islam, 229–34.↩︎

For more on the GMP, see ibid., Chapters 2 and 7; and Alain Boyer, L’institut musulman de la mosquée de Paris (Paris: Centre des hautes études sur l’Afrique et l’Asie modernes, 1992).↩︎

Khalil Merroun and Isabelle Lévy, Français et musulman: est-ce possible? (Paris: Presses de la Renaissance, 2010), 90–92.↩︎

Ministry of Habous and Islamic Affairs, Nashrat Al-Munjazat, Activity Report (Rabat: Ministry of Habous and Islamic Affairs, 2009–2016).↩︎

Abdelkrim Belguendouz, Le traitement institutionnel de la relation entre les Marocains résidant à l’étranger et le Maroc, 2006/06 (European University Institute, Florence: CARIM-RR, 2006), 7, http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/6265/CARIM-RR2006_06.pdf.↩︎

Brand, Citizens Abroad; Hajar El Moukhi, “La Foundation Hassan II pour les Marocains résidant à l’étranger: Quel apport pour les MRE et la question migratoire?” (Masters Internship Report, Mohammed V University, 2008), 21.↩︎

De Haas, “Between Courting and Controlling,” 21–23.↩︎

Francesco Ragazzi, “Governing Diasporas,” International Political Sociology 3, no. 4 (2009): 378–97.↩︎