Anne Monsour

TELL ME MY STORY: THE CONTRIBUTION OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH TO AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE AUSTRALIAN LEBANESE EXPERIENCE

Abstract

This study of the Lebanese in Australia from the 1880s to 1947 was an exercise in historical retrieval. Because the lives of the early immigrants were bound by racially based colonial and then state and federal legislation, archival records are a rich source of information about Lebanese and their status as a non-European, non-white, immigrant group in the context of a white Australia. Due to a deliberate silence about the past, most descendants did not know they were classified as Asian and were unaware of the specific difficulties their parents and grandparents faced as a consequence. When memories collected in oral history interviews and information from archival sources are woven together, it is possible to tell a more complete story. Sometimes, commonly held beliefs about the migration story are challenged; in other cases, the experiences of individuals make more sense when placed in a wider context.

INTRODUCTION

The men who governed the British colony of Australia following the dispossession and near destruction of its First Peoples, were of the view that they were creating “a white man’s country.”1 This goal was acted upon when, in 1901, the new Commonwealth quickly legislated to expel the Pacific Islanders brought to work in the Queensland cane fields and to prevent “nonwhites” from entering the country.2 At the time, these actions were part of a worldwide movement to protect white privilege.3 Australia’s restrictive immigration policies were so successful that in 1947, 99 percent of Australians were white, and 90 percent of those were of “British and Irish origin.”4

As a result of the massive scale of non-British immigration after 1947 and the official replacement of the White Australia Policy in the 1970s by a universalist approach to immigration, Australia’s population is now more diverse and includes people from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. An official policy of multiculturalism allowed Australians from diverse and previously excluded backgrounds a visibility and a voice. However, not all Australians welcomed these changes. Anxieties about the changing composition of the Australian population were given voice with the rise of Pauline Hanson and her One Nation Party, and with the election of the Howard Government in 1996. In its first term, this Government introduced stricter skill and family reunion requirements, harder language tests, and abolished the Office of Multicultural Affairs and the Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research.5 Since the Howard era (1996–2007), immigration policy, border protection, the ethnic and religious composition of the Australian population, and Australian values have been the subjects of intense public debate. Despite its apparent demise in 2001, the return of the One Nation party, now stridently anti-Muslim and anti-refugee, shows that anxieties about the composition of the Australian population and the future of the “Australian way of life” are still prevalent.

The Lebanese are not exempt from questions about their acceptability, particularly in Sydney where approximately seventy percent of Lebanese Australians live. The racial violence at Cronulla beach, Sydney, in December 2005 revealed the extent of hostility toward Lebanese.6 While for some the anti-Lebanese sentiments expressed at Cronulla were an aberration, for others they were a continuation of the “anti-Muslim, anti-Lebanese and anti-Arab sentiment” that emerged in Australia during the first Gulf War and has intensified since then.7 However, as this paper will show, the issues faced by Lebanese Australians today reach back to the nineteenth century. The first Syrian/Lebanese immigrants entered a hostile environment and encountered significant social and legislative racial discrimination. Then, as now, the discourses of race and religion were dominant and set the boundaries within which the Lebanese negotiated their position in Australian society.

Remembering the night in 1941 when his Lebanese grandfather was arrested by the Commonwealth Police as an enemy alien, David Malouf wrote:

My father never told us how he had managed it, or what happened, what he felt, when he went to fetch his father home. If it changed anything for him, the colour of his own history, for example, he did not reveal it. It was just another of the things he kept to himself and buried. Like the language. He must, I understood later, have grown up speaking Arabic as well as he spoke Australian; his parents spoke little else. But I never heard him utter a word of it or give any indication he understood. It went on as a whole layer of his experience, of his understanding and feeling for things, of alternative being, that could never be expressed. It too was part of the shyness between us.8

Malouf tells us, his father “was not much of a talker,” and “never told stories, as our mother did, of his family and youth.”9

Like Malouf, I too realized well into my adult years that I had missed learning about my family’s Lebanese heritage. I was only twenty-one when my father died. My twenties were busy years. I missed my father a great deal and with the birth of my first child, I realized how much I had lost and how little I really knew about his life. My mother had an excellent memory but she had only come to Australia in the 1950s; my father had arrived here in 1926. Fortunately, I was still able to talk with my uncle, Joseph. As a sixteen-year-old, he had shared my eighteen-year-old father’s journey to Australia, and they had worked together for the next forty-two years, mainly as general storekeepers in Biggenden, a small, Queensland town. So, my research into the history of the Lebanese diaspora in Australia was partly a personal journey, what Barry York described as “an emotional need on the part of some to learn about their parents’ or grandparents’ part in Australian history and not just about ‘everyone else’s’ parents or grandparents.”10

Compiling a literature review for my thesis in the early 1980s, I found that although Lebanese were in Australia from the late 1870s, with a few exceptions, they had been generally ignored in the recording of Australian history.11 What had been written focused on the post-World War II period and was generally not the work of historians but of social scientists. In 1979, Abe Ata claimed the Lebanese community in Australia had not been the subject of any systematic study. While publications in the 1980s revealed a growing interest in the Lebanese as a group within Australian society, in 1989 Jim McKay could still point to “a dearth of sociological or historical research about the Lebanese, ‘one of Australia’s oldest immigrant populations.’”12 So, one of the initial premises for my doctoral research was that the Australian Lebanese story had been ignored by historians; however, I soon realized this was too simplistic an assessment.13 As my research progressed, it was obvious there had also been a deliberate silence by the early immigrants and as a result their children and grandchildren knew little about their early years in Australia.14 The “shyness” described by Malouf was, it became apparent, a common experience within the Australian Lebanese diasporic community.

After almost three decades of researching, writing, and telling the Australian Lebanese story, I continue to be surprised at the depth of this silence. I am also surprised, but heartened, at how details about the history and experiences of the early immigrants, the results of an academic research project, can provide Lebanese immigrants’ children and grandchildren with answers to puzzling questions, and enable a more informed understanding of immigrant lives, personal and communal. In the case of the early Lebanese migrants in Australia, because parts of the story had been effectively silenced by the immigrants themselves, the history that emerges from the archival records is essential to understanding the individual and community migration story. However, what is also telling, are the stories and ideas that have been passed on. These, along with the silences, inform personal and community memory and understanding.

A story often told by descendants of early Lebanese immigrants is that Australia was not the intended destination. Apparently, when he disembarked at the port of Melbourne, Nicolas Antees “firmly believed he had set foot on American soil.”15 Similarly, the Fachry brothers thought they had “boarded a ship in Beirut to go to America.”16 According to Calile Malouf’s daughter, Minnie, her father, mother and the other Syrian/Lebanese with whom they shared the six-month boat journey to Australia in 1892 had thought they were going to America.17 America was undoubtedly the favored immigrant destination and while it is possible some of the first immigrants arrived in Australia accidently, there is evidence that after 1880 Lebanese were deliberately coming to Australia. According to the Australian Kfarsghab Lebanese Association, Massoud El-Nashbi of Besharri arrived in Australia in 1880 but returned to Lebanon after only six months, having made good money selling souvenirs from the Holy Land.18 His story of success and positive reflections on Australia and its people encouraged others, including the sons of Father Gebrail El-Fakhri, the parish priest of Besharri, to immigrate to Australia.19 In turn, reports of their success inspired others, including a group of seven men from the village of Kfarsghab, to follow.20 These seven were the first in an ongoing chain of migration from Kfarsghab to Australia.21

By the mid-1880s, people were coming to join relatives or friends already in Australia. In 1885, a group of immigrants were forced to land at Launceston, Tasmania, rather than Melbourne, their planned destination.22 The ship’s Commander recounted that at Port Said the group had asked for “passage to Australia” and when pressed for a more specific destination said they wanted to go to Melbourne “where one of them had a brother.”23 In another example, although Calile Malouf’s daughter believed her father’s intention was to reach America, it is also possible that he planned to come to Australia because there were already Maloufs and others from their hometown of Zahle settled there.24 George Nasser Malouf arrived at the port of Melbourne in June 1886 and Darwish Moosa Faddoul Malouf a few years later in June 1889.25 Throughout the 1890s, having met the five year residence requirement, several Maloufs were naturalized in the colony of New South Wales: Joseph Tannous in June 1895; Rastom in December 1896; Michael in January 1897; Abraham Zahran, Canoi, and Michael Tarbia in 1898; Louis Moses and Amin Shahin (Maloof) in 1899.26 As Joseph George (J.G.) Malouf was naturalized in August 1893, he had been in New South Wales since at least August 1888. A graduate of the Syrian Protestant College in Beirut and with some experience in business, he immediately established himself in Sydney as a draper and merchant.27 His brother, Jonas, arrived in Sydney in February 1889 with his wife, Mary and their two children.28 They moved to Queensland in 1890 and by 1892 had established a drapery store in Ipswich. Perhaps this is why, when Calile and his family arrived in Queensland in November 1892, their first place of residence was Ipswich.29

At the outset, I quickly learned the archival records were not about the Lebanese. In Australia, all immigrants from the Ottoman region of Greater Syria were identified as “Syrians” and classified as Turkish subjects. Most were from the area now known as Lebanon. While both descriptions were technically correct, generally these people did not have a modern national identity but were loyal instead to their family, religious sect, and village.30 One of the first consequences of migration for the early immigrants was accepting a Syrian identity. Early records show the immigrants did indeed adopt this categorization at least in their official and public discourse.

From the 1890s, community leaders and individuals embraced the use of the term “Syrian.” This is reflected, for instance, in a key disagreement that occurred between J.B. Manouk and J. G. Malouf, reported in several Sydney newspapers in 1895.31 When the former claimed he was a Turkish consular agent, thereby positing himself as the community leader, the latter stated that not only was this news to him but also “to the Syrian people generally.”32 An unnamed “Syrian Merchant” corroborated J.G. Malouf’s position, stating that J.G. Malouf was “much better known. . . than all the other Syrians to a great number of Australians” and a man who “in all matters of Syrian interest . . . is foremost.”33 A further example shows that the Syrian immigrants advocated for a positive image of the Syrian community in Australia. Salem Bracks, “Syrian merchant and British subject,” wrote to a Sydney paper, Evening Star, in 1896 correcting its claim that “Ezekial Joseph,” an alleged thief, was “a Syrian.”34 Bracks claimed Joseph was from Baghdad and that, despite “much recent calumny and misrepresentation,” the Syrian community was “one of the most law-abiding people on the face of the earth.”35 By the first decades of the 1900s, the term Syrian was applied to community organizations and associations. A 1909 booklet commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the Redfern municipality mentions the United Syrian Association, the Syrian Committee of South Sydney Hospital, and the Ottoman Association.36 In 1926, the Syrian Ladies Association was active in Sydney raising money for charitable causes.37 Alexander Alam, who in 1925 was the first person of Lebanese descent to enter parliament, referred to himself in 1922 as “an Australian Syrian.”38

It is clear from the records that the widespread adoption of the term “Syrian” by the early immigrants was for reasons of political expediency and not the result of a lack of education, of literacy, or of a sense of a particular identity. What archival records reveal is that many of the immigrants were literate and generally appreciated that in order to be recognized and visible in Australia, they needed to identify in a way that the Australian Government at the time classified them.39 This political astuteness is further evidenced when, as is described later, Syrian immigrants seeking naturalization claimed various European nationalities, including Turkish, in order to evade discriminatory legislation. It is this strategy rather than poor literacy that explains why many archival records include incorrect birthplaces while in earlier records the immigrants were able to list their local village or district. For example, in 1887, Joseph Hottar described himself as a native of Mount Lebanon in Syria; while in 1890, both Joseph Woby and Joseph Farret note their birthplace as Bschere, Mt Lebanon.40 Solomon Mansor stated “Kafre-Hona in Lebanon, Syria” as his birthplace when he applied for naturalization in 1897.41 Nicholas Doumani and Khaleel Saleeba42 were born in Zahle, Mount Lebanon, in Syria; George Michael Gallety in Baalbek, Syria; Elias and Eftiemus Saleeba in Rashyia/Rashayia, Syria;43 and Antoureen, Solomon Ostophan Saleeba in Monte Libbon.44 Apart from listing the name of their distinct town or district, these early immigrants also managed to transliterate their names into English, challenging another common migration story told by descendants that name changes were the result of illiteracy on the part of the immigrant and/or ignorance on the part of government officials. But they were also astute enough, as the following example reveals, to adapt their names for the Australian context in which they were now settled. In response to a comment by a reporter that “George Dan” was “Not exactly a Syrian name,” J.G. Malouf responded: “Well, no; his right name is Nicholas Domani; but he thought that would be rather difficult for English people, so he changed it.”45

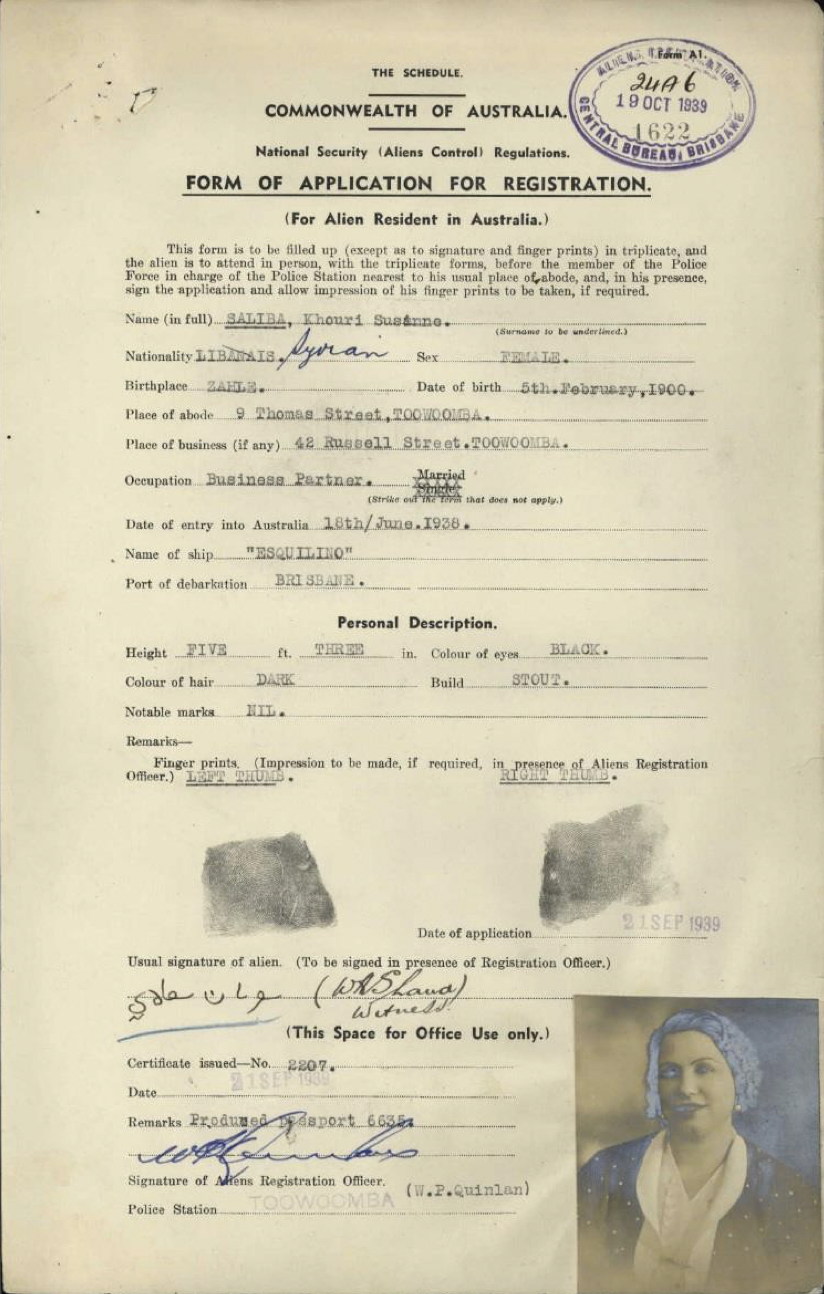

Despite the creation of Greater Lebanon in 1920, in Australia the term “Syrian” was still in general use until the 1940s. When Suzanne Khouri Saliba came to Australia in 1939, she recorded her nationality as “Libanais” on the Certificate of Registration of Alien form, but on the Form of Application for Registration, “Libanais” is crossed out and replaced with “Syrian”46 (Figure 1). There is however evidence that by the late 1930s, being Syrian was no longer acceptable to Lebanese for reasons that resonate with the contemporary situation in Australia and worldwide. In 1938, for example, the ConsulGeneral of France informed the Minister of External Affairs that as “Lebanon is a predominantly Christian State, while Syria is a Mohammedan one,” the Lebanese do not want to “be called Syrians,” as this could lead to the belief they are Muslim.47 Consequently, from 1 January 1939, Lebanese and Syrian nationals were for the first time and thereafter, classified separately in official records.48 In common with their counterparts in the United States, by asserting their Christian credentials and hence differentiating themselves from Muslim Syrians, these immigrants were validating their “whiteness.”49

When asked in oral history interviews, older informants remembered the use of the term Syrian, but those born after World War II, including me, did not. Within one generation, being Syrian had become a fading memory. As their primary loyalties were to family, village and religious sect, in the absence of negative consequences, perhaps it was of little personal as opposed to public or official import to these immigrants what government officials decided to call them. Nevertheless, knowing the early immigrants were identified as Syrians is critical, as demonstrated, to accessing the Australian Lebanese story.50

My journey through the archival records brought a more important realization and one which most descendants did not know: based on the geographic location of their homeland, in Australia, Syrian/Lebanese were classified as Asian. This classification means the experiences of the early immigrants have more in common with the Chinese and Indians than with other migrants from the Mediterranean region such as Greeks, Italians, and Maltese. It also situates the Australian Lebanese story within the context of “the global ascendancy of the politics of whiteness” and hence, transnational history.51 The evolution and consolidation of the White Australia Policy determined the course of Lebanese settlement in Australia and is fundamental to the Syrian/Lebanese migration story.52

THE IMMIGRATION RESTRICTION ACT OF 1901

The immediate effect of the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 was to end a period of unrestricted migration and stall the dramatic increase in Syrian/Lebanese arrivals that had occurred in the 1890s. After 1901, the decision to come to Australia was no longer as simple as being able to afford the fare; for Syrian/Lebanese, entry was now dependent on either passing the dictation test, having an exemption permit approved by the Minister, or being considered eligible for an exemption permit as a former resident or the wife or child of a man not deemed a “prohibited immigrant.”53 The dictation test, which could be administered in any European language, was designed to exclude Asians and other non-whites and not intended as a genuine education test. Because fifty-three individuals, including four Syrians in 1902 and one in 1903, passed the test in its first three years of operation, amendments were soon made which ensured its effectiveness to exclude non-whites.54 Between 1910 and 1946, for example, not one person passed the dictation test.55

The effectiveness of the dictation test meant that only those Syrian/Lebanese who were dependent on a relative already settled in Australia or those who were able to prove former domicile had any chance of entering the country. Therefore, after 1901, by constraint rather than design, chain migration was the only possible pattern of migration for Syrian/Lebanese. This, in turn, consolidated a pattern of dispersed geographic settlement which developed because Syrian/Lebanese were segregated in commercial occupations, such as hawking and shopkeeping partly due to blocked employment opportunities caused by legislative discrimination in employment.56 As new arrivals depended on family and friends to find employment and accommodation, many were introduced to hawking and shopkeeping, occupations in which their relatives were already established often in regional Australia.57 It became the norm that one or two members of a family, usually the original immigrants, settled in a particular place and then, after bringing them to Australia, settled other siblings or relatives from Lebanon in the same district.58 A further consequence of restricted migration was that until the 1960s the number of people born in Syria/Lebanon and living in Australia was always small: there were 1,803 and 1,886 Syrian/Lebanese in Australia in 1921 and 1947 respectively; whereas, in 1966, there were 10,668 and by 1996, 70,224.59 Conceivably, small numbers and dispersed geographic settlement throughout the vast Australian continent had an unavoidably negative impact on the possibility of cultural maintenance.60

Immigrant children grew up isolated in country towns, their experience of being “Lebanese” often limited to their extended family. Reflecting on her childhood in north Queensland, Hazel explained:

We were the only ones in Innisfail—but there was a family in Babinda, and there were four or five in Cairns and there was one in Tully, and at one stage, one of the uncles was in Mossman. But Dad either put them into business or put them on the land, because he had farms then. And so they were all around us and we grew up literally with all our first cousins.61

In an environment in which only complete assimilation was tolerated, these immigrant children were continually faced with their foreignness and worked hard to hide their difference. Two sisters who grew up in the north Queensland town of Cairns, for example, recalled how, when their father played Arabic music, they “would go around closing all the windows. There were millions of windows. We’d be all night long closing windows so no one would hear.”62 Furthermore, isolation from other Arabic speakers and an observed intolerance towards the use of any language other than English significantly contributed to the loss of Arabic as a viable language for the second and third generations.63 These were not conditions conducive to cultural continuity.

While the number of Syrian/Lebanese directly affected by the operation of the Immigration Restriction Act was small, for these individuals and their families the cost, both personal and financial, was high. For some, it meant the choice of continued separation from their family or leaving Australia. In 1902, for example, Joseph Abood, a licensed hawker who had lived in Australia for almost five years, applied to have his wife and child join him; however, his request that his family be exempted from the provisions of the Immigration Restriction Act was refused.64 Similarly, despite being a successful businessman with stores in Sydney and Toowoomba, Anthony Coorey’s request in 1902 for his brother Michael to join him in Australia as a business partner was refused.65 A number of prosecutions of Syrians as prohibited immigrants made it quite clear to the individual, their relatives and friends, and because cases were widely reported in newspapers, the Australian public, that they were considered undesirable immigrants.66

Syrian/Lebanese leaving Australia and intending to return needed a certificate of domicile until 1905, and thereafter, a certificate of exemption from the dictation test.67 The application for exemption included a statutory declaration, character references, and photographs of full face and profile.68 In correspondence with the Commonwealth government, Wadiah Abourizk, a spokesperson for Syrian/Lebanese in Australia, claimed it was unfair and humiliating that like criminals, Syrians had to provide handprints and be photographed in four different positions when leaving the Commonwealth.69 Syrian/Lebanese who left without obtaining a certificate of exemption or who had left before federation had to prove prior domicile to be re-admitted without passing the dictation test. This was a complicated process. Departure from Australia had to be verified and photographs to confirm an individual’s identity provided.70 Police examined claims regarding previous residence, inquired as to the person’s character, and ascertained whether “any wellknown European residents” could identify the individual under investigation.71

After fulfilling these requirements, some applications were successful. Jacob Mahboub and his family, for example, were granted re-admission to Australia in 1903 after the birth certificates for three of his children were accepted as satisfactory proof of former domicile.72 Following a thorough and satisfactory investigation into his claim, Kessian Assad, who after eighteen years residence, had left Australia in 1907 without a certificate of exemption and sought re-admission in 1913, was granted permission to land, subject to being satisfactorily identified and paying the one pound fee for a certificate of exemption from the dictation test.73 Mansour Coorey, however, was not so fortunate, and his case illustrates the personal cost of the Immigration Restriction Act. Coorey arrived in New South Wales in January 1892, but returned to Syria in October 1899 because his father was ill and he needed to attend to family affairs.74 Due to the illness and subsequent death of both his parents, he remained away longer than anticipated.75 Coorey returned to New South Wales in December 1907 to find he was now a prohibited immigrant. Based on the understanding he would visit the Tamworth district where he had been in business and then proceed to New Zealand, he was granted a threemonth exemption certificate with Jacob Moses, a Syrian merchant, and Joseph Dahdah, a Syrian priest, acting as sureties for the compulsory £100 bond.76 Coorey’s intention was to use the time to prove former domicile and be granted permission to remain permanently in Australia.77 Supporting his case, Jacob Moses argued Coorey was forced to return to Syria because of family circumstances but, as evidenced by his continuing business interests in New South Wales and the sale of all his possessions in Syria, his intention was always to return.78 If deported, Coorey faced absolute ruin.79 Despite evidence confirming his former residence, good character and continuing business connections, and appeals on his behalf, no extension of exemption was granted and Coorey was required to leave Australia. When he did not readily comply with this request, he was declared an illegal immigrant and given a deportation order.80

In contrast with other Asians, Syrian/Lebanese were not totally excluded although their entry was restricted and carefully monitored. At the discretion of consecutive Ministers limited numbers with well-established family or friends were allowed to enter the Commonwealths.81 This lenient treatment was the result of three factors that distinguished Syrian/Lebanese from their Indian and Chinese counterparts. Firstly, with the exception of a small number of Druze (an offshoot of lslam), the Syrian/Lebanese who came to Australia before 1947 were Maronite, Melkite, and Orthodox Christians.82 Because after 1901 only people who already had family or friends in Australia were granted entry, the migration remained predominantly Christian until the late twentieth century, and the Lebanese Muslims who came to Australia in the 1950s and 1960s were probably initially sponsored by Christian friends.

Secondly, from the outset Syrian/Lebanese migration to Australia was a family movement. In 1884, for example, Daher and Karma Aboud arrived with their six children, while Mary and Jonas Malouf came with two young sons in 1889.83 A group of immigrants from “Beyrout in Syria” forced to land at Launceston, Tasmania in 1885, included a number of women.84 By 1888, there were concerns about a “rapidly increasing influx” of “Syrians and Arabs.”85 The observation that these Syrians “bring their women with them” provides further evidence that women participated in the early migration.86 In January 1893, the Syrian population of Redfern, Sydney, was estimated as “at least 1500” and included “men, women and children,” while in Broken Hill there were twenty-eight Syrian men and women.87 At the time, the presence of women was a significant difference between Syrian/Lebanese and other Asians in Australia and ultimately contributed to their more favorable treatment.88 Unlike the Indians and Chinese who were predominately male, Syrians had families to support, so it was not feared that their earnings would be exported overseas.89 Also, the presence of women from the initial migration meant Syrian/Lebanese men, unlike their Chinese and Indian counterparts, were not seen as a threat to white women or to the goal of racial purity.90 Interestingly, in the United States the presence of Syrian women did not allay similar concerns due to an overriding fear these “racially inferior” immigrants would produce children who “could never be ‘Americanized.’”91 Not only were women part of the early migration to Australia, as in the United States experience, there is also evidence some women initiated migration.92 Annie Barket was a widow for ten years before she came to Australia in 1894 and started a twenty-four year career as a hawker in Broken Hill.93 Adele’s grandmother went to the United States, returned to Lebanon, and then, in 1900, came to Australia without her husband but with her eldest daughter.94 Similarly, Rose’s grandmother left her husband and four sons in Lebanon and with a group of friends came to Australia where she worked as a hawker and a hotel proprietor.95 The actions of these women did not necessarily meet with the approval of other Syrian/Lebanese. In 1892, a Syrian male reacting to persistent accusations that Syrian men were lazy and sent their wives out to work as hawkers, explained:

. . . it is against our wishes and laws that any woman goes out at all; but what are we to do? They come here without their husbands and consequently they are their own masters, and we have no power to prevent them; but what all of us most earnestly wish is that Parliament will pass an act prohibiting any Syrian female from obtaining a licence.96

Reflecting this attitude, Mansoura Betro, a storekeeper, who in 1896 had been in Australia for ten years and whose husband lived in Syria, was accused by a male Syrian storekeeper of “being an immoral woman.”97

Thirdly, Syrians were treated more leniently because, although there is no question they came from geographic Asia, in appearance they were more like southern Europeans. As a result, there were ongoing doubts about their actual racial identity. Officially, how to deal with Syrians in relation to the Immigration Restriction Act caused “considerable difficulty” because bureaucrats were not convinced they belonged to “the black, brown and yellow races.”98 Reviewing the status of Syrians in 1914, both the Secretary and Chief Clerk of the Department of External Affairs observed that in regard to appearance and religion, Syrians were more European than Asian.99 The reasons Syrians were treated leniently not only confirm that racial and religious preferences were the basis of the White Australia Policy but also highlight an ongoing, and at times advantageous, ambiguity about the identity and status of Syrian/Lebanese.

THE WHITE AUSTRALIA POLICY

As well as restricting the entry of non-Europeans, the White Australia Policy aimed to make life so uncomfortable for those already living in Australia that they would leave. Asians and therefore Syrian/Lebanese experienced legislative discrimination including exclusion from certain industries and occupations, denial of the right to vote or stand for parliament, exclusion from citizenship, restrictions on the ability to hold leases and own property, and disqualification from social services such as the invalid and old-age pensions.100 Exclusion from citizenship was the most significant disadvantage faced by the early immigrants. In the colonial period access to naturalization varied from colony to colony but from 1904 to 1920, Syrian/Lebanese immigrants, nationwide, experienced total exclusion from citizenship based on their racial classification.101

The mandatory police reports used to assess an individual’s suitability for naturalization, created a conspicuous process of surveillance. Police reported on an applicant’s character and suitability and on the accurateness of the information provided in an application.102 Records show police inquiries were thorough and that the immigrants knew they were under scrutiny. The police interviewed the applicant, other Lebanese, local residents, and the character witnesses, and were routinely required to determine whether the applicant was “a coloured man.”103 They also noted the religion of an applicant and after 1920, whether the applicant had been registered as an alien, what the applicant’s conduct during the war entailed, and investigated if there was any evidence that the applicant was disloyal to the King.104 Additionally, partly due to discrimination in employment, most of the early immigrants, male and female, began their working life in Australia as hawkers.105 As hawking was a licensed activity and “alien” hawkers were closely monitored, many of the early immigrants had intimate experience of being scrutinized.

The impact of this scrutiny, its imposition and the effect it had on the daily lives of these immigrants, only intensified in relation to the enemy status of Syrian/Lebanese in Australia during World War I. The Government knew that Syrian/Lebanese did not support the Turkish regime, but they nevertheless classified them as enemy aliens during that war.106 This understanding on the part of the Australian Government actually and ironically afforded the community exemptions. The exemptions, though, were not effectively communicated to the immigrants or to the general public, and the immigrants were not just subject to surveillance but also unjustly discriminated against. Many had already been refused naturalization despite a long period of residence in Australia. Now, they, and even their Australianborn children, were required to register at the local police station and to notify the police if they were leaving town or changing their address.107 Thomas Rey, for example, registered as an alien of Syrian origin in December 1916.108 Subsequently, Rey, an itinerant laborer, was required to notify the police every time he moved seeking work. Between 1918 and 1921, he submitted eleven Notice of Change of Address forms as he moved between the far north Queensland towns of lnnisfail, South Johnstone, Gordonvale, and Babinda.109 Australian-born women who had acquired Syrian nationality by marriage were also obliged to register as aliens.110 Joseph Mansour Fahkrey, a travelling optician, who had lived in Australia since he was an infant, was charged as an enemy alien “in possession of a motor car without the written permission of the senior officer of police in the district in which he resided.”111 The internment of Nicholas William Malouf of Gatton in 1917 and charges brought against some Syrian/Lebanese for breaching Regulation 5 (1) of the War Precautions Aliens Registration Regulations of 1916, confirmed the seriousness of their enemy alien status.112 Throughout the war, the Lebanese opposed their status as enemy aliens and demonstrated their worthiness through actively supporting the war effort by raising funds and by many of the Australian-born joining the expeditionary forces.113

Archival records leave no doubt the immigrants, unlike their children and grandchildren, knew they were classified as Asian, which resulted in specific disadvantages like the lack of voting rights and limitations on their ability to own property.114 Understanding their predicament, Syrians, and their advocates, used their physical appearance, Christian religion, and the presence of a significant proportion of women to argue they were white, European, and Christian and hence should be granted equal status. There is extensive evidence that as individuals and as a group Syrian/Lebanese strongly objected to being considered Asian, and were eventually successful in achieving a degree of sympathy with this position.115

In 1900, arguing against his exclusion from naturalization in colonial Queensland due to being a single Asiatic male, Richard Arida claimed he was actually the native of a European state.116 Section 5 of the Commonwealth Naturalization Act of 1903 disqualified “all aboriginal natives of Asia” from naturalization.117 When Syrian/Lebanese were subsequently told they were ineligible for naturalization because Section 5 applied to them, many challenged this classification. One applicant, for example, argued modern Syrians were white or Caucasian and no colored stigma had “ever been attached” to them “in any era.”118 Another declared he was “not an aboriginal native of Syria but a whit[e] man of good English education,” and that the term “aboriginal” could not refer to him because he was trilingual, literate in English, French, and Arabic, and a Christian.119 Syrian/Lebanese also acted as a group to repudiate their identification as Asian. In 1909, they petitioned the government to modify their status in relation to the Immigration Restriction Act because they were white and European.120 Writing to the Prime Minister almost a year later, one of the signatories to this petition further noted that: “Syrians are Caucasians & they are a white race as much as the English. Their looks, habits, customs, religions, blood, are those of Europeans, but they are more intelligent.”121

The records also show the immigrants acted to circumvent discriminatory legislation. When I began going through naturalization records at the Queensland State Archives, I found a relative who claimed to be born in Pleven in Europe. I doubted this was true but checked with the family. Once alerted, I began to see a pattern. I was undertaking a nominative study so I was looking at records based on name rather than place of birth. In the Queensland records, I found several Syrian/Lebanese who claimed to be born somewhere in Europe. Specifically, seventeen were naturalized as European Turks (the Bosporus Strait separates Turkey in Europe from Turkey in Asia), eleven as Greeks, and six others as having been born either in Crete, Malta or Cyprus.122 I found a similar trend in the Commonwealth records which I also searched based on name rather than place of birth. Between 1904 and 1920, a significant number of Syrian/Lebanese were granted naturalization despite Asians being prohibited from citizenship.123 Anyone who stated their birthplace as Syria or Mount Lebanon was refused naturalization; whereas, those who claimed a European birthplace, usually Turkey but also Greece, Italy, Russia, France, and Bulgaria were successful.124

The evidence Lebanese were deliberately recording false birthplaces is extensive. Especially convincing are the single files in which the applicant has claimed two birthplaces, depending on the current legislation. Richard Arida refused naturalization as a single, Asiatic male in 1900, was subsequently naturalized in 1906 as a Turk.125 When Joseph Abdullah applied for naturalization in 1907 as a native of Syria, Mount Lebanon, he was rejected.126 Five months later he re-applied stating his birthplace as Constantinople, Turkey.127 More evidence that Syrian/Lebanese were deliberately giving false birthplaces is found through linking separate files revealing that a failed application was sometimes followed with a new application stating a European rather than Syrian birthplace. Saleem Elias made an application in 1914 stating he was French; a Syrian person with the same name and matching particulars had made an unsuccessful application seven years earlier.128 While, Joseph Coorey’s application for naturalization was refused in February 1904, in December of the same year, an application by a person with the same name and personal details, including having a wife and five children living in Syria, was successful.129 The critical difference between the first and second application was the place of birth. In the second application, Coorey claimed Athens as his birthplace.130

By linking State and Commonwealth files, it is obvious changes in stated birthplace in naturalization applications were quite deliberate and based on an understanding of the legislation. Jacob Adymee who was refused naturalization as an “Assyrian” in Queensland, later applied successfully for Commonwealth naturalization, this time claiming to be Greek.131 When questioned in 1921, Davis Saleam admitted he had lied about his place of birth because he knew it was his only chance to become naturalized.132 He was not alone. In my sample of naturalization applications by Syrian/Lebanese immigrants between 1904 and 1920, at least fifty percent claimed to be born in Europe.133 The recording of incorrect birthplaces on official records is most often attributed to language difficulties and bureaucratic incompetence. In this case, it is quite obvious the immigrants deliberately labeled themselves European Turks or claimed another European birthplace in order to circumvent discriminatory legislation and be granted naturalization.134 I expected the label “Turkish” to be unacceptable to Syrian/Lebanese, particularly because in the individual and collective imagination many had emigrated to escape Turkish persecution. Yet, whatever their feelings about the Turks, in the Australian diaspora the records show Syrian/Lebanese were prepared to be officially Turkish if it meant they could circumvent their racially defined exclusion from citizenship.

The actions of the early immigrants reveal a political astuteness in their response to legislative discrimination. Syrian/Lebanese immigrants were not passive victims. Claiming a European identity was quite evidently the most effective strategy in the face of anti-Asian legislation. However, through letters, petitions and deputations to parliamentarians, Syrian/Lebanese also lobbied against their classification as Asian and their subsequent status in relation to discriminatory legislation. These actions are contrary to what might be expected from a group stereotyped as poor, illiterate peasants, and it is evident many of the earliest immigrants were neither poor nor uneducated.135 Joseph George Malouf, who was educated at the Syrian Protestant College in Beirut, started in business in 1888 soon after his arrival. This suggests that he arrived with the necessary capital to undertake this task.136 The brothers, Richard and Joseph Arida were both well-educated, spoke several languages and had traveled extensively.137 In 1891, Joseph Chehab and Abraham Kahled were described as “men of some social standing and of no little education” who spoke “English with more or less fluency, and are altogether of superior class.”138 Daher Aboud was well-educated and had brought a lot of money into the colony, while Mary Michael was literate in three languages.139 Furthermore, the bureaucrats charged with determining the status of Syrian/Lebanese in Australia observed they were generally “moderately educated but occasionally men are met who are highly trained and who speak several languages.”140

As the Australian colonies, in the pre-federation period, moved towards adopting policies to guarantee a white nation, educated Syrian/Lebanese publicly argued for a more positive view of Syrians. Abraham Khaled contended Syrians who were “clean, civil, energetic and economical” should not be confused with Afghans and Hindus; while Joseph Arida claimed Syrians were Christian, European and generally industrious, hospitable and honest.141 Similarly, a “Syrian Merchant” noted Syrians were Caucasians, “the same family as the English” and “if the police courts are an authority we are a law abiding class, and thus desirable colonists.”142 Concerned about the implications of the pending Coloured Races Restriction Bill in New South Wales in 1896, a deputation of Syrians argued they should be treated differently to other Asians as they were not colored and because they did not “send money away to Asia” but instead lived, worked and spent their money in the colony.143

LIVING IN A WHITE AUSTRALIA

Aside from the immigrants’ efforts to challenge legislation that discriminated against or marginalized them, they also, in their domestic lives, sought to ameliorate their “outsider” status by presenting as “white.” The archival evidence tells a story about the intrusiveness of the implementation of racially discriminatory legislation which meant the early Syrian/Lebanese immigrants knew in a very practical sense the key to overturning the discrimination they faced was being accepted as white, European, Christian, and English speaking. Considering the obstacles they faced, it is not surprising they focused on achieving acceptability, and hence equal status, in their new home. To this end, they did not tell their children about their experiences as outsiders. Instead, they readily assimilated into mainstream churches, insisted their children only speak English, and passed on little information about their Lebanese heritage. Settlement was dispersed and there was intense pressure to conform and not attract attention.144 This is the context in which the children and grandchildren of the early immigrants had to negotiate life in the new society and in which questions about the continuity or discontinuity of cultural practices and in particular, Arabic language, need to be considered.

Despite the efforts of the first generation to conceal their experiences of being racially undesirable, their children were also acutely aware it was better to obscure their difference. Generally, when interviewed or surveyed, descendants preferred to focus on the positives rather than the negatives of living in Australia. A common observation was that Lebanese were “great mixers” and very good at “blending in.” As one respondent put it: “I think the big thing with the Lebanese [is] they seem to assimilate very easily into the community.”145 Notwithstanding this emphasis on the positives about their lives in Australia and their involvement in the community, there was also an acknowledgement of the constant need to overcome their outsider status. Fared articulated a common response by the second generation: “I felt we were singled out and the only way you could gain their respect was to prove yourself and you were on your mettle all the time to be that bit better than the other person.”146 Likewise, Malcolm’s reflection highlights the pervasiveness of outsider status in the small country towns in which many of the early immigrant families lived:

We were the only Lebanese family in Clermont and there was one Greek family . . . We were the Lebanese, they were the Greek and because of that we had a sort of. . . almost felt as if we were buddies and everyone else was the rest. The rest were Australian and we were a bit different. . .147

With hindsight, descendants frequently expressed a strong regret about what they did not know and what they had refused to learn from their parents. Monica, for example, recalled her desperation not to be identified as other than English, and expressed regret at the lifelong consequences of having accepted that her background was somehow inferior:

You were kind of looked down on because you weren’t English. Yet you were never game to mention the fact; you kept quiet about the fact of what you were; and I regret now that I never learnt to read or write [Arabic] . . . And we were terrified and when any of our school friends came, if mum started to talk in Arabic we nearly used to die, . . . and now I could kick myself because I’m old enough . . . to know . . . we were just as good as all those other people. . .148

Another interviewee recalled that when her mother spoke in Arabic to her in front of her peers, she was so embarrassed she would desperately try to disown her:

‘Don’t take any notice of that lady. She’s not my mother, she’s Chinese.’ I always remember that. When my mother used to sing out in Arabic to me. . . I used to say to my mates, ‘Don’t take any notice of her, she’s Chinese!’ I was real embarrassed and ashamed.149

Although the immigrants could adopt English, attend mainstream churches and embrace the Australian way of life, as their children were well aware, it was not possible to change physical appearance:

They’ve got Lebanese traits but they try to hide them. Their Lebanese traits are there but they won’t accept that they’re there. . . I always had a resentment about it [being Lebanese] because it was always a burden to carry when I was a child. . . it was a burden. It sort of set you apart before anything else. . . you had no one else to associate with.150

While it is understandable that the early immigrants, wanting their children to prosper in Australia, thought it better to hide their experiences as outsiders and emphasize the future rather than the past, for their children, this silence had profound consequences:

I guess it would not be putting too fine a point on it to say that I am dispossessed of my heritage due to the need for my parents to ‘assimilate,’ not so much for their own sake but to ensure that their children had the best possible chance in a new country.151

. . . language is like a tool and it is not so much the language that is important as is the history. . . that is lost when a language is lost; and when we lose history we lose something of the understanding of how we got to be where we are and we lose the ability to place our social and political structures, our mores, beliefs, relationships, and world view into a context that allows us to challenge those things and build on (change) what we have and know in order to get at the truth of how things are.152

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, I was surprised by the intense silence about the past; by the significant effects of the White Australia Policy on the personal and collective lives of the immigrants and their descendants, and by the patterns I observed which indicate little actually changes. Syrians were perceived as undesirable and a threat in the 1890s. In early twentieth-century Australia, the Syrian/Lebanese presence challenged the success of a nation building project based on race and religion. The White Australia Policy successfully contained their numbers but when there was a visible migration in the 1950s concerns were again raised. As well as being described as “dirty” and “primitive,” some of these “poor types,” whose “standards of living do not conform to those of Western civilization,” were “not even white.”153 In the late 1970s there were similar public concerns when Lebanese fleeing the civil war were granted entry to Australia apparently as refugees. This was a general misunderstanding. In reality, they were treated as quasi-refugees because they had to have relatives already living in Australia who would guarantee accommodation and other needs.154 Despite the official adoption of multiculturalism and the apparent acceptance of cultural diversity, in twenty-first century Australia, the acceptability of its Lebanese residents is once more the subject of intense public debate, especially in Sydney where almost three quarters of the Lebanese in Australia live. Suggestions that the violent confrontations at Cronulla in 2005 were the result of Lebanese, particularly but not only Lebanese Muslims, refusing to accept core Australian values are difficult to sustain because, as the historical records show, the current unease about Lebanese does not represent a clear and unambiguous break with the past. The settlement experience of Lebanese in Australia has never been comfortable and there have always been doubts about their desirability as residents and citizens.

FIGURES

NOTES

Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds, Drawing the Global Colour Line: White Men’s Countries and the Question of Racial Equality (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 144.↩︎

Ibid., 137–38.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

James Jupp, “Waves of Migration to Australia,” in Stories of Australian Migration, ed. John Hardy (Kensington: New South Wales University Press, 1988), 26. Although challenging, the Irish immigrant experience in Australia varied from that described by David Roediger in The Wages of Whiteness (London: Verso, 1991). The Irish component of the early Australian immigrant population was significant. According to Patrick O’Farrell, by 1921 half a million, or one in three Australians, were of Irish descent (“Landscapes of the Irish Immigrant Mind,” in Stories of Australian Migration, ed. John Hardy (Kensington: New South Wales University Press, 1988), 33). These immigrants were not a homogeneous group but fitted into three general sub-groups: the Anglo-Irish, Irish Protestants (largely Ulster Presbyterian), and Gaelic Catholics (Ibid., 42). Although they, particularly the Irish Catholics, faced disparaging stereotypes, there is little evidence that the Irish in Australia were not considered white.↩︎

Stephen Castles, “Multiculturalism in Australia” in The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins, ed. James Jupp (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 810.↩︎

“Mob violence envelops Cronulla,” Sydney Morning Herald, 11 December 2005, http://www.smh.eom.au/news/national/mob violence-envelops-cronulla/2005/12/11/l134235936223.html.↩︎

See Nelia Hyndman-Rizk, “‘Shrinking World’: Cronulla, Anti-Lebanese Racism and Return Visits in the Sydney Hadchiti Lebanese Community,” Anthropological Forum 18, no. 1 (March 2008): 37–55.↩︎

David Malouf, “The Kyogle Line,” in Neighbours: Multicultural Writing of the 1980s, ed. Ron F. Holt (St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1991), 69.↩︎

Ibid., 67.↩︎

Barry York, “Australian Ethnic History Survey: A Report,” Australian Historical Association Bulletin 68 (September 1991), 38–42.↩︎

In Jens Lyng, Non-Britishers in Australia: Influence on Population and Progress (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1935), 181–88, Lyng discusses Syrians as one of the “Brown” races; in Alexander T. Yarwood, Asian Migration to Australia: The Background to Exclusion 1896–1923 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1967), 141–50, Yarwood includes a chapter on Syrian immigration.↩︎

McKay’s book, Phoenician Farewell, a study of three generations of Lebanese Christians in Sydney; Ata’s publications, based on research within the Lebanese community in Melbourne; and Andrew and Trevor Batrouney’s The Lebanese in Australia, published as part of the Australian Ethnic Heritage Series, helped redress this situation. Jim McKay, Phoenician Farewell: Three Generations of Lebanese Christians in Australia (Melbourne: Ashwood House, 1989); Abe Ata, “The Lebanese in Melbourne: Ethnicity, Inter-ethnic Activities and Attitudes to Australia,” Australian Quarterly 51, no. 3 (1979): 37–54; Abe Ata, “Pre-war and Post-war Lebanese Immigrants in Melbourne,” Australian Journal of Social Issues 14, no. 4 (1979): 304–16; Abe Ata, “Marriage Patterns among the Lebanese Community in Melbourne,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology 16, no. 3 (1980): 112–13; Andrew Batrouney and Trevor Batrouney, The Lebanese in Australia (Melbourne: Australasian Educa Press, 1985).↩︎

Generally, my research is based on a nominative approach (locating individuals by name) using a combination of sources such as naturalization case files, alien registration records, hawking records, newspapers, Post Office directories, church records, questionnaires, interviews, and family histories.↩︎

Anne Monsour, “What Jiddi Didn’t Tell Us: Using Documentary Evidence to Understand the Settlement of Syrian/Lebanese Immigrants in Queensland, Australia from the 1880s to 1947,” in Lebanese Diaspora: History, Racism and Belonging, ed. Paul Tabar (Beirut: Lebanese American University, 2005), 59–60.↩︎

Andrew Batrouney and Trevor Batrouney, The Lebanese in Australia (Melbourne: Australasian Educa Press, 1985), 21.↩︎

Ibid., 30.↩︎

Minnie Jacobson, interview with author, Brisbane, 1991.↩︎

Australian Kfarsghab Association, A Concise History of Kfarsghab Migration: Centenary Jubilee of the Kfarsghab Migration: 1880–1980 (Sydney: Australian Kfarsghab Association, 1980), 10.↩︎

“Emigration to Australia 1870–1900,” Australian Kfarsghab Association, accessed 20 July 2016, http://www.kfarsghab.com.au/kfarsghab-migration/.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Australian Kfarsghab Association, A Concise History of Kfarsghab Migration, 16.↩︎

Launceston Examiner, 13 February 1885, 2.↩︎

Launceston Examiner, 14 February 1885, 3.↩︎

Jacobson, interview.↩︎

National Archives of Australia (NAA): A712, 1890/Q7795, Naturalization, George Nasser; NAA A712, 1897/F1658, Naturalization, Darwish Moosa Faddoul Malouf.↩︎

“Naturalization Index: 1834–1903,” New South Wales State Records, accessed 22 February 2016, https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-andresearch/guides-and-indexes/naturalization-index.↩︎

Souvenir to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Incorporation of the Municipality of Redfern, 1859–1909 (Sydney: McBarron, Stewart & Co., 1909).↩︎

Jonas Malouf, Naturalization Application, 2 June 1902, Hom/A39, Queensland State Archives (QSA).↩︎

Calile Malouf, Naturalization Application, 07866, 12 June 1899, Hom/A35, QSA.↩︎

Almost every discussion of Syrian/Lebanese immigrants makes this point. See the following as examples: Philip K. Hitti, The Syrians in America (New York: George H. Doran, 1924), 25; Michael W. Suleiman, “Early Arab-Americans: The Search for Identity,” in Crossing the Waters: Arabic-Speaking Immigrants to the United States before 1940, ed. Eric J. Hooglund (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987), 41, 47; Kemal H. Karpat, “The Ottoman Emigration to America 1860–1914,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 17, no. 2 (May 1985): 175–209.↩︎

Evening News (Sydney), 4 February 1895, 3; Truth (Sydney), 10 February 1895, 4; Evening News, 11 February 1895, 2; Sunday Times (Sydney), 24 February 1895, 8.↩︎

Evening News (Sydney), 11 February 1895, 2.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Evening News (Sydney), 14 July 1896, 7.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Souvenir to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Incorporation of the Municipality of Redfern.↩︎

Sydney Morning Herald, 12 November 1926, 5.↩︎

Evening News, 21 June 1922, 6. In 1925, Alexander Alam became the first Syrian/Lebanese Australian to enter parliament.↩︎

The early immigrants were from the Ottoman region of Greater Syria, so their classification as Syrians and as Turkish subjects were both technically correct. In practice, though, these people did not identify with these modern national identity labels; they were instead loyal to their family, religious sect and village. Almost every discussion of Syrian/Lebanese immigrants makes this point. See, for example, Hitti, The Syrians in America, 25; Michael W. Suleiman, “Early Arab-Americans,” 41, 47; Kemal H. Karpat, “The Ottoman Emigration to America,” 175–209; Marlene Khoury Smith, “The Arabic-Speaking Community in Rhode Island: A Survey of the Syrian and Lebanese Communities in Rhode Island,” in Hidden Minorities: The Persistence of Ethnicity in American Life, ed. Joan H. Rollins (Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1981), 141.↩︎

Joseph Hottar, 10 September 1887; Joseph Woby, 11 January 1890; Joseph Farret, 28 May 1890, SCT/CF 34, Certificates of Naturalization and Associated Papers, 1860–1902, QSA.↩︎

Solomon Mansour, Certificate of Naturalization No: 245, 3 April 1897, State Archives and Records, New South Wales.↩︎

NAA: A712, 1902/Q4350, Naturalization, Khaleel Saleeba.↩︎

NAA: A712, 1902/P9273, Naturalization, Elias Saleeba; NAA: A712, 1900/L124, Naturalization, Eftiemus Saleeba.↩︎

NAA: A711, 2657, Memorial of Naturalization, Antoureen, Solomon Ostophan Saleeba.↩︎

Sunday Times (Sydney), 27 January 1895, 3.↩︎

NAA: BP25/l, Lebanese, Saliba; Alien Registration Papers, Queensland.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1938/32817, Classification of Lebanese and Syrian citizens in Australia.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

For an excellent examination of these issues see Sarah M.A. Gualtieri’s study of early Syrian immigrants in the United States: Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009).↩︎

In this paper, the term Syrian/Lebanese is used to refer to the early immigrants from modern Lebanon.↩︎

Lake and Reynolds, Drawing the Global Colour Line, 9.↩︎

Anne Monsour, “Negotiating a Place in a White Australia: Syrian/Lebanese in Australia, 1880 to 1947, A Queensland Case Study,” (PhD thesis, University of Queensland, 2004).↩︎

Barry York, Studies in Australian Ethnic History, Number 1, 1992: Immigration Restriction, 1901–1957 (Canberra: Centre for Immigration & Multicultural Studies, 1992), 2.↩︎

Ibid., 13–20.↩︎

Ibid., 25–67.↩︎

This predominance of self-employment was partly the result of widespread racially based legislative discrimination in employment which expanded significantly between 1901 and 1920. In the state of Queensland for example, there were more than thirty separate Acts restricting occupational freedom. See: Disabilities of Aliens and Coloured Persons Within the Commonwealth and Its Territories, 1920, Prime Minister’s Department, Al/1, 21/13034, NAA, Canberra; List Showing Restrictions or Disabilities In Queensland Applicable to Aliens, 1943, A/7513, 1234/43, QSA, Brisbane; Andrew Markus, Australian Race Relations 1788–1993 (St. Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1994), 120.↩︎

Anne Monsour, Not Quite White: Lebanese and the White Australia Policy 1880 to 1947 (Brisbane, Post Pressed, 2010), 115–26.↩︎

For examples see: Anne Monsour, “‘Better Than Anywhere Else’: Lebanese Settlement in Queensland, 1880–1947,” Queensland Review 21, no. 2 (2014): 142–59.↩︎

Census of Australia 1901–1996 cited in Jim McKay and Trevor Batrouney, “Lebanese Immigration Until the 1970s,” in The Australian People, ed. Jupp, 556.↩︎

See Monsour, Not Quite White, 127–47; Anne Monsour, “But Why Can’t You Speak Arabic?” 10th Anniversary Journal (Coogee: New South Wales: Australian Lebanese Historical Society, 2010), 35–55.↩︎

Hazel Francis, interview with author, Brisbane, 1995.↩︎

E. Ogden and L. Lucus, interview with author, Brisbane, 1995.↩︎

Monsour, Not Quite White, 134.↩︎

NAA: BP342/l, 9706/570/1902, Joseph Abood, Application for Entry of Wife and Son.↩︎

NAA: A9, Al902/35/95, Anthony Coorey.↩︎

Age (Melbourne), 29 December 1905, 5; Advertiser (Adelaide), 30 December 1905, 10; Sydney Morning Herald, 28 December 1906, 5; Worker (Wagga), 2 April 1908, 5; Advertiser, 25 December 1906, 6; Express and Telegraph (Adelaide), 26 December 1906, 4; West Australian (Perth), 3 December 1908, 7; Examiner (Launceston), 11 January 1906, 8; Australian Star (Sydney), 22 January 1906, 5.↩︎

A.T. Yarwood, Asian Migration to Australia: The Background to Exclusion 1896–1923 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1967), 67.↩︎

NAA: B13, 1930/16979, Mary Sedawie, Application for Exemption from the Dictation Test.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1910/3915, W. Abourizk regarding the position of Syrians under the Immigration Restriction Act.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1914/8059, Kessian Assad, Application for Re-admission.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

NAA: BP342/l, 6731/636/1903, Jacob Machbub, and Family, Correspondence relating to the Re-admission of the Machbub Family into Australia.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1914/8059, Kessian Assad, Application for Re-admission.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1910/6222, Mansour Coorey Illegal Immigrant.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Yarwood, Asian Migration to Australia, 149.↩︎

In Kamal S. Salibi, The Modern History of Lebanon (Delmar, New York: Caravan Books, 1977), xviii, Salibi describes the Druzes as the “followers of the Fatimid Caliph al Hakim (996–1021) who proclaimed his own divinity in the early eleventh century, deviating from traditional Isma’ilite Shi’ism.”↩︎

Daher Aboud, Naturalization Application, 10 January 1899, Col/73(a), QSA; Jonas Malouf, Naturalization Application, 2 June 1902, Hom/A39, QSA.↩︎

Brisbane Courier, 20 January 1893, 7.↩︎

Western Star and Roma Advertiser, 14 July 1888, 2.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Brisbane Courier, 20 January 1893, 7; Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 19 January 1893, 4.↩︎

Yarwood, Asian Migration to Australia, 163.↩︎

Ibid., 143–44.↩︎

Ibid., 144.↩︎

Evelyn Shakir, Bint Arab: Arab and Arab American Women in the United States (Westport: Praeger, 1997), 79–81.↩︎

Shakir, Bint Arab, 28–33; Akram Fouad Khater, Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870–1920 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 64–70.↩︎

Barrier Miner, 5 August 1948, 4.↩︎

Adele and Josephine Shear, interview with author, Toowoomba, 1993.↩︎

Mick and Rosa Sardie, interview with author, Brisbane, 1990.↩︎

Evening News, 26 November 1892, 7.↩︎

Dubbo Liberal and Macquarie Advocate, 29 April 1896, 3.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1914/20363, Syrians under Immigration Restriction Act.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1921/13034, Disabilities of Aliens and Coloured Persons in the Commonwealth and its Territories; List showing restrictions or disabilities in Queensland applicable to Aliens, 1943, A/7513, 1234/43, QSA.↩︎

Queensland, Aliens Act of 1867, 31 Vic. no. 28, ss. 6-12; Commonwealth of Australia, Naturalization Act, no. 11 of 1903, s. 5.↩︎

Anne Monsour, “Whitewashed: The Lebanese in Queensland, 1880–1947,” in Arab-Australians Today: Citizenship and Belonging, ed. Ghassan Hage (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2002), 24; Monsour, “What Jiddi Didn’t Tell Us,” 67–70.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Anne Monsour, “Traders by Nature or Circumstance: The Occupational Pathways of Early Syrian/Lebanese Immigrants in Australia,” Labour and Management in Development 15 (2014),

http://www.nla.gov.au/openpublish/index.php/lmd/article/view File/3091I3908.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1921/11220, Boulus John Peter Mellick Naturalization.↩︎

Major Wallace Brown to Commissioner of Police, Brisbane, November 1914, 1268.M.38, A/11954, QSA; Gerhard Fischer, Enemy Aliens: Internment and the Homefront Experience in Australia 1914–1920 (St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1989), 75.↩︎

NAA: BP4/3, Misc Syrian Rey T, Thomas Rey, Syrian, Alien Registration.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

NAA: BP4/3, Misc Syrian Malouf EE, Elsie Elizabeth Malouf, Syrian, Alien Registration.↩︎

Bendigo Advertiser, 6 August 1918, 3.↩︎

Monsour, Not Quite White, 79–82; NAA: BP4/3, Annie Abrahams, Syrian, Alien Registration; NAA: BP4/3, Maroon Beetres, Syrian, Alien Registration.↩︎

Monsour, Not Quite White, 82.↩︎

“Disabilities of Aliens and Coloured Persons,” Al/1, 21/13034, (NAA): “List Showing Restrictions or Disabilities in Queensland Applicable to Aliens,” A/7513, 1234/43, QSA.↩︎

Monsour, Not Quite White, 57–60; NAA: Al, 1914/20363, Syrians under Immigration Restriction Act.↩︎

Marsland, Jarvis & Co., to G.H. Ryder, Under Secretary, Home Secretary’s Office, Brisbane, 6 June 1900, in-letter 08813, Hom/A29, QSA.↩︎

Commonwealth Naturalization Act, no. 11 of 1903, s. 5.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1905/3040, Richard Saleeby, Application for Naturalization.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1904/6496, Alfred Moses Naturalization.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1910/3915, W. Abourizk regarding the position of Syrians under the Immigration Restriction Act.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

While technically Syrian/Lebanese were Turkish subjects, it was unusual for them to identify as Turks and in government documents (except during World War I) they were most often classified as Syrians. The point here is not so much that they identified as Turks but that they used the descriptor European to ensure they would not be considered Asiatic Turks. Anne Monsour, “Becoming White: How Early Syrian/Lebanese in Australia Recognised the Value of Whiteness,” in Historicising Whiteness: Transnational Perspectives on the Construction of an Identity, eds. Leigh Boucher, Jane Carey, and Katherine Ellinghaus (Melbourne: RMIT Publishing in association with the School of Historical Studies, University of Melbourne, 2007), 124–32.↩︎

Monsour, “What Jiddi Didn’t Tell Us,” 74–76.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Marsland, Jarvis & Co., Solicitors to G. H. Ryder, Under Secretary, Home Secretary’s Office, 08813, 6 June 1900, Hom/A29, QSA; NAA: Al, 1905/8109, Richard Dominique Arida, Naturalization.↩︎

Joseph Abdullah to Home Secretary, 7760, 9 June 1903, Col/74(a), QSA.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1905/4069, Joseph Abdullah, Naturalization.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1922/5710, Salem Elias, Naturalization; NAA: Al, 1907/11197 Salem Elias, Naturalization.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1904/1061, Joseph Coorey, Naturalization; NAA: Al, 1904/10441, Joseph Coorey, Naturalization.↩︎

130 NAA: Al, 1904/10441, Joseph Coorey, Naturalization.↩︎

Jacob Adymee, Memorial, 14 January 1903, 3802/1903, Col/73(a), QSA; NAA: Al, 1905/1506, Jacob Adymee, Naturalization.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1921/23734, Davis Saleam Naturalization.↩︎

Monsour, Not Quite White, 65–67.↩︎

Ibid., 66–70.↩︎

Najib E. Saliba, “Emigration from Syria,” in Arabs in the New World: Studies on Arab-American Communities, eds. Sameer Y. Abraham and Nabeel Abraham (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Center for Urban Studies, 1983), 39; Michael W. Suleiman, “Early Arab-Americans: The Search for Identity” in Crossing the Waters, ed. Hooglund, 39; Batrouney and Batrouney, The Lebanese in Australia, 20; McKay, Phoenician Farewell, 31.↩︎

Souvenir to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Incorporation of the Municipality of Redfern.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1905/8109, Richard Dominique Arida, Naturalization; NAA: Al, 1930/376, Joseph Dominique Arida, Revocation of State Certificate Naturalization.↩︎

Argus (Melbourne), 8 January 1891, 6.↩︎

Daher Aboud, Naturalization Application; 12 October 1903, 12232/1903, Col/74(a), QSA.↩︎

NAA: Al, 1914/20363, Syrians under Immigration Restriction Act.↩︎

SMH, 3 February 1893, 2; SMH, 27 February 1893, 8.↩︎

SMH, 28 October 1896, 5.↩︎

SMH, 23 October 1896, 3.↩︎

These pressures are articulated in responses by descendants of Syrian/Lebanese immigrants to the Language Maintenance and Loss Survey, 2010, in Monsour, “But Why Can’t You Speak Arabic?” 35–55; and in oral history interviews and questionnaire responses collected as part of my PhD research.↩︎

Calile Malouf, interview with author, Brisbane, 1995.↩︎

Fared Tooma, interview with author, Brisbane, 1991.↩︎

Malcolm Nasser, interview with author, 1995.↩︎

Monica Simpson, interview with author, 1993.↩︎

Hazel Yarad, interview with author, Brisbane, 1995.↩︎

Tofe Monsour, interview with author, Sydney, 1989.↩︎

Language Maintenance and Loss Survey, 2010, in Monsour, “But Why Can’t You Speak Arabic?” 49.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Sunday Herald (Sydney), 13 May 1951, 6; Cairns Post, 14 May 1951, 3; West Australian, 17 July 1951, 2; West Australian, 18 June 1951, 1; Argus, 19 June 1951, 1; Advertiser (Adelaide), 19 June 1951, 1.↩︎

Sunday Herald (Sydney), 13 May 1951, 6; Cairns Post, 14 May 1951, 3; West Australian, 17 July 1951, 2; West Australian, 18 June 1951, 1; Argus, 19 June 1951, 1; Advertiser (Adelaide), 19 June 1951, 1.↩︎