Balca Arda

SELF IMAGE MAKING OF THE DIASPORIC ARTISTS: “THE SOUSVEILLANCE STRATEGIES IN THE DIASPORIC ART OF MIDDLE EASTERN DIASPORA”

Abstract

I explore in this paper how Middle Eastern diaspora’s art that I call “selfie art” resists against surveillance techniques and technologies in everyday life beyond territorial borders such as public stigma and stereotyping in the host countries in North America. My analysis is composed of three stages: (1) The study of self-surveillance as a method of sousveillance and how self-exposure becomes an object of art; (2) the relation between self-design and politico-ethical allegiance in the visual abundant society through the case of the imagery of Middle Eastern diaspora; (3) ethnographic observations in diasporic art events as well as in-depth interviews with artists and content analysis of various online and offline artworks. I argue that the sousveillance strategies of diasporic art coincide with the resisting communities that negotiate with technologies of surveillance to lead a state of equiveillance in the visual public sphere.

INTRODUCTION

The September 11 attacks and aftermath, the legalization and normalization of the suspension of due legal processes and the constitutional rule of law, the institutionalization of torture, the use of mass surveillance and the routine collection of information on innocent citizens, and arbitrary detention without trial have primarily forced a Middle Eastern diaspora to reflect a public self, an alternative image than the stereotyped one, to secure themselves from institutional and social stigma. Boris Groys accentuates this process of necessary self-image building to confront the image of the self; to correct, to change, to adapt, to contradict the image of the self for anybody who comes to be covered by the mass media, the social media, the surveillance system, and cameras.1 Following the same line, a diasporic figure from the Middle East has to design oneself and must create an individualized public persona not only in the context of a visual society but also for not being mistaken for a homegrown terrorist in the public sphere of the host country. Diasporic artists from the Middle East produce artworks that reflect on these activities of self-exposure that I call “selfie artworks.” What distinguishes the selfie artworks of the diaspora artists from the Middle East from the everyday acts of selfie making shared on social media or for family fun lies in its mobilization of selfexhibition as an excessive and hence critical mimicry of politics as policing and the visual economy based on socially dominant stereotypical imagery of “Middle Eastern diaspora.” By doing so, they become agents of their own surveillance, and hence, exercise sousveillance in their selfie making art practices. The idea of sousveillance, developed by Steve Mann,2 has been envisaged as resistance to surveillance technologies through “seeking to increase the equality between the surveiller and surveillee, including enabling the surveillee to surveil the surveiller, uncovering the Panopticon and undercutting its primacy and privilege.”3 In this article, I will study diasporic artworks produced through various different visual practices as examples of sousveillance techniques. These visual artworks serve as selfie taking for the artists in the sense they constitute both auto portrait and autobiography as well as the product of their design capacities. I argue that these art practices of selfsurveillance disclose the role of design in identifying and declaring allegiance to a specific socio-political stance and category. Sousveillance in Mann’s understanding allows people to be lifelong photographic artists rather than merely suspects.4 In my case of research, performers of selfie art are already professional artists. However contemporary art has already updated the boundary between the amateurish and professional image production in the sense that professionalism means the professional production of amateurish images for artists. Throughout the paper, I explore the ways in which such societal boundaries and otherization are criticized through contemporary art, and how sousveillance techniques can be adapted to question societal stereotypes and identity precepts.

METHOD OF RESEARCH

Contemporary art refuses to rely on a grand narrative of history but instead prefers to focus on discourses and personal narratives. The role of particular identities in the making and interpretation of visual arts has been recognized in the art world and this exposes the contingency of value which reveals the unavoidable ideological bias in art, art criticism, art curating, and so forth.5

Hence, the artist and the artwork are perceived and promoted together as a total output in connection with the contemporary art scene. In my methodology, I follow this kind of art making strategy in the contemporary arts. In order to conduct this study of the sousveillance techniques in these artistic visual self-representations of the Middle Eastern diaspora in North America, I draw on various methodologies of content analysis, one-to-one qualitative interviews, and participant observation. Thus, I critically explore both artists and artworks in connection to contemporary art’s precept. I conducted interviews with several diasporic artists engaging in the contemporary art scenes in Canada and the United States. Artists that conduct self-image making use one or combine various types of visual art practices such as painting, photography, movie making, and installation while they follow contemporary art’s interdisciplinary and anti-professional approach that seeks out taboos and boundaries of different art practices and exploits them. In my content analysis of these visual artworks, I investigate the artistic context in these self-surveillance acts together with cultural themes and contemporary trends and issues affecting the Middle Eastern diaspora such as those used in defining “terrorism” in reference to “Middle East” with otherization, disidentification and universality in artistic stances and through the discourse of contemporary art and major debates on surveillance literatures.

The selected material was collected on the grounds of its experienced capacity of inciting public discussions about Middle Eastern diaspora, diaspora from Muslim majority countries, and Muslim communities in Canada and the United States. Some of the diasporic Canadian and American artists that I explore in this article are 2FIK, Negin Farsad, Aymann Ismail, Sabrina Jalees, and Ana Lily Amirpour. The artists whom I interviewed and whose artworks I analyze are selected among those who and which already reach beyond the artist’s activist political environment and meet with not only diasporic audiences but also the larger public through the media. I look at the artists who are promoted in the offline and online sphere as “diasporic artist from the Middle East.” I analyze their artworks that are labelled as the “Middle Eastern,” “Muslim,” “brown,” or by their country of origin in order to identify their convergent and divergent ways of artistic narrations and relate them to diasporic subjectivity while making them distinguished from the North American mainstream art environments.

My objective in exploring the selfie art of the Middle Eastern diaspora is to analyze the role of art in exposing Middle Eastern diasporic subjectivity and explore the terms of sousveillance in artistic strategies in deconstructing, reproducing, and changing the mode of relating between visibility and political allegiance in the public sphere. Doing so has significant consequences for the question of the current assumed dynamics of social inclusion and exclusion in today’s society of visual abundance and the culture of vigilance. It also highlights the implication of art in mediating reconciliation and more importantly disrupting ways of understanding the “partition of sensible”6 to denounce the interpretation of politics as policing between categorically differentiated interest groups.

SELF-SURVEILLANCE AND CONTEMPORARY ART

While the consolidation of security society and the regulation of constant surveillance predominates in everyday life of the age of terror, self-surveillance as part of sousveillance, has emerged as a need to record, store, and analyze one’s social participation and mobility for self-security in the sense of creating an alibi towards future dataveillance intrusions.7 Sousveillance, describing a form of a watchful vigilance from underneath, brings out a self-reflective responsibility.8 Therefore, the selfie culture cannot only be assumed to be related to late capitalism’s trend of narcissistic consumption but the fact that everyone needs to learn how to be his own witness and expose a self to the surveillance-generated society. As such, selfie making as a part of sousveillance strategies mediate a resistance to surveillance technologies. Jamais Cascio, co founder of Worldchanging, emphasized that people can become subjects rather than objects monitored by social institutions of power9 through selfmonitoring.10

As such, in today’s world of visual abundance in the social sphere, everyone can be considered an artist because citizens of the contemporary world are responsible for their self-images. That is why “self-design is a practice that unites artist and audience alike in the most radical way—not everyone produces artwork, everyone is artwork. At the same time, everyone is expected to be his own author.”11 Groys claims that contemporary art should be analyzed not in terms of aesthetics but rather in terms of a poetics which prioritizes production and art producer rather than perception and perceiving subject. In the absence of the fixed transcendental signification and contents of the modernist age, Groys argues that the design and self-design of the body presents the ethical, social, and political dimension of the subject in the contemporary world and in contemporary art. Following Gray’s line of argument, because the artist becomes part of the artwork in today’s art scene, autopoetics as the production of one’s own public self becomes the focal point of contemporary art. The artist’s body was largely veiled or repressed within modernism as the inferior component of the body-mind dialectic. As Rebentisch puts forward, this idea implies that participation in art must be conceptualized as partaking in the universality that: “The beholder, listener, spectator, or reader, by relating to the work, likewise is to overcome her own empirical situatedness.”12 However, for contemporary art, the artist is highly attached, personally, sentimentally, romantically and emotionally to her/his artwork as it is a form of selfie creation. This selfie art is also more than personal, it embraces individuality because it has to do with character, environment, cultural background, talents, and desires. In other words, the contemporary art regime resides in the peculiar shift from generic history to discourse and personal narrative. As a matter of this trend in the art scene, artists from the Middle Eastern diaspora living in Canada and the United States inevitably respond to the neo-orientalist view of the Middle East and the image of the frightening Muslim an-iconicity in their contemporary artworks. In that sense, while Middle Eastern subjectivity is reduced to a shape in the sense of physical attributes through mainstream discourse, the Middle Eastern diasporic artistic reaction works to deconstruct and reproduce these mainstream Middle Eastern stereotypes and imaginaries to claim for or to search for their own understanding of the self.

Artists of Middle Eastern diaspora by taking over the surveillance themselves in their selfie art make the observed person be the observer and turn the hierarchy of surveillance upside down. As such sousveillance derives from the fact that “power like beauty is in the eye of the beholder” and these artworks document the logic that the best way to protect privacy is to give it away.13 In that sense, resistance to surveillance is assumed to be exercised, in part, through self-exhibition. However, Foucault argued that consciousness of being monitored by unseen observers can lead people to adopt the norms and rules of the surveillors and discipline their behaviors in accordance to the logic of surveillance; therefore, the panopticon succeeds in gaining further power through individual disciplinary efforts. In light of this concern, these diasporic artworks of self-exposure related to Middle Easternness and stereotyping not only raise the question of panopticism today and the assumed connection of self-design with politics and subsequent otherization but also the envisioned range of resistance and the possibility of oppositional art.

POLITICS OF SELF-IMAGE: DESIGN AS THE MARKER OF POLITICO-ETHICAL STANCE

The design of the self has a prominent political power in the current society of visual communication. The seemingly innocent question of “where are you from originally” can perfectly conceal and reveal the terms of social inclusion and exclusion but more importantly, when articulated this question mostly brings to light today’s way of identification and identifying one’s politicoethical stance through physical traits and image setting in public sphere. It remains difficult for anyone to claim to be someone without “performing differences” and “self-design” techniques in public in the contemporary visually abundant society of selfie making. Therefore, the institutional and social surveillance technologies act and react to specific designs and attached information on body traits.

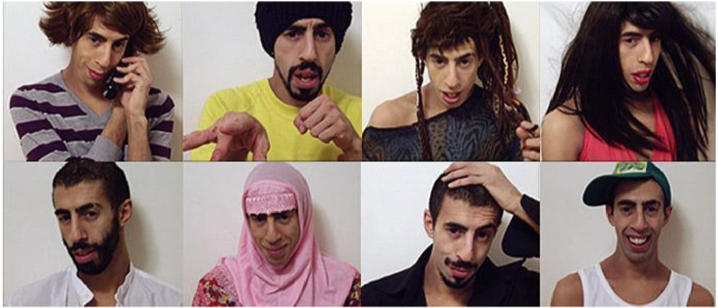

2FIK is a Montreal based artist originally from Morocco. His artworks range from selfie-photos to short videos. In an interview over Skype in July of 2014, he stated that his works deal with identity, gender and prejudice, and told me that he sees himself as a stateless person: “. . . involved in three different cultures [the Canadian, the French and the Moroccan] but even if those societies are dear to me, none of them sees me as fully of them [because of his accent, his attitude, etc.].”14 He uses his own body for his art and plays all of the characters in his short videos and photo stories. Hence, he uses his art to question his own personal identity. He explains that such self-exposure in means of surveillance of different characters that he can design himself in his artworks can dissolve the dominant comprehension of Middle Eastern diasporic subjectivity. 2FIK explains the inspiration for his art to me:

You need to handle and deal with the perceptions of yourself, you do not have a choice, they look at you and they think of it. The perception of Muslim people is so negative since 9/11. I totally assume this is how you can change perceptions. I am not Muslim anymore but I still look like one.

His serial artwork Identities is composed of various photos including these characters seen above [see Figure 1]. 2FIK plays all these characters which look so different and even antagonistic to each other through stereotypic visual traits and signs that he manifests through his body. In Identities among the characters, all of which are living in Montreal, he plays Abdel; a hypocritical practitioner of Islam with his beard and macho attitude; Fatima, Abdel’s wife, who is raised to be a mother and not an independent woman, who however gets stronger throughout the photo story; Kathryn, an ambitious and overconfident intern in fashion industry and a woman who is not attached to any man except those she has regular sex with including Abdel; and Marco, both a macho and feminine schizophrenic homosexual man who is part of a secret gang and mugs homophobic straight people (“The Fagger Rangers”).15 2FIK told me that he uses the image to get the immediate response and plays with the viewer’s own lens, perspective, and prejudices. Thus, 2FIK asserts his presence in public space allowing people to see another side of the North African face. Thereupon, the transparency he achieved through his selfie-art becomes the alibi in the sense of open statement that he does not conform to the dominant visual coding.

The “if you see something, say something” quote of the homeland security campaign in the United States totally exemplifies the ways of otherization. An act becomes a suspicious activity according to “who” and “what” s/he is doing when one sees an event and identifies it as “potentially dangerous” according to dominant imagery. Hence, some bodies are more recognizable as out of place, and thus, “already read and valued in the demarcation of social spaces.16 As Sara Ahmed emphasizes, the system of “neighborhood watch” proceeds through the recognition of stranger through her/his image. Ahmed notes, recognition operates as a visual economy: it involves ways of seeing the difference between familiar and strange others as they are represented to the subject.17 She argues that, “The definition and enforcement of the good ‘we’ operates through the recognition of others as strangers: by seeing those who do not belong. . . the stranger as the one who is out of place.” That is why David Tyrer claims that “bodies classified as Muslim are based not on the agency of subjects but on appeals to Islam.”18 Thus selfdesign becomes a marker of politico-ethical allegiance. For example, both Muslims and non-Muslims recognize “Muslims” through this self-design rather than principles or through specific agency in public sphere. As one of my informants, the Indian-American stand-up artist Azhar Usman emphasized in my interview with him in Chicago in June 2013:

In America, the term Muslim gained political currency under an inclusive and paradoxically exclusive sense. It does not include Caucasian Muslims, Bosnians. It does not include Indonesians . . . or black people,[. . .]—it includes Indian people who are not Muslims. A whole category—stupid in so many levels. . .

To be sure, the Middle Eastern diaspora differs considerably within themselves in numerous cultural traits, in their identification and identifications through ethnicity, religion, nation, history and their communal practices in the host country. However, there is a slippage and systematic confusion amongst the terms of Middle East, Islam, Arabness, and “brown” skin in the common sense as such Middle Eastern subjectivity is not a religious identity—ethnicity—homeland referring to one’s beliefs, practices, but an image. That is why non-Muslims have also been victimized by anti-Muslim hate crimes as in the case of Wade Michael Page who likely mistook Sikhs for Muslims as he gunned down six Sikhs at a Milwaukee temple in 201219 or when hipsters were mistaken for ISIS militants in 2015.20

What is attached to “Middle Eastern” is the skin color, name, familial origin and so forth, hence more than the Muslim or religious connotation of identity. This is because the Middle Eastern Diaspora in North America reflects some kind of a mixed identity with racial and regional connotations enclosed within the informal definition of the term. Here, Mehdi Semati argues that “brown, once the signifier of an exoticism, has come to embody the menacing Other in the today’s geopolitical imagination”21 and the expansion of the security state. In this context, not Islamophobia but Middle Eastern phobia posits Muslims, non-Muslims, secular, non-religious, veiled, and nonveiled subjects as carriers of alterity because it redefines culture as the carrier of Middle Eastern spiritual inheritance codified in some instances on “brown” skin or in others in a Middle Eastern name or nativity as a signifier of potential terror. This reasoning seems to originate from the scene in the movie Battle of Algiers, based on the Algerian war for independence22 against French colonialism in the 1950s: Algerian female fighters dye their hair blond to easily pass through French security checkpoints and reach French cafe to place their bombs in. Homi Bhabha draws here a line of mimicry and inauthenticity as “a sudden awareness of inauthenticity, of authority’s constructed and assumed guise, is the menace of mimicry.”23 As Achille Mbembe notes in his discussion of the suicide-bomber in the movie: “To kill, one has to come as close as possible to the body of the enemy. To detonate the bomb necessitates resolving the question of distance, through the work of proximity and concealment.”24 Correspondingly, the fact that the online selfie photos of the ISIS sympathizer gunman, Omar Mateen,25 of mass shooting in Orlando Gay Club became a source of curiosity in every news story derives from the fact that Omar Mateen was wearing unofficial NYPD t-shirts in these selfies. For instance, such disaccord between his Islamist allegiance and the image of American boy has been referenced to support the claims such as “ideology is often a mask” and “motives can simply be a final excuse for mass murder” in the case Omar Mateen’s mass shooting.26

Therefore, common sense does not acknowledge that “every terrorist is Muslim so that every Muslim can be a terrorist” but that “every terrorist is whether brown skinned or Muslim majority country related” hence the Middle Eastern diaspora is suspect. This results in the necessity of proof for the Middle Eastern diaspora member that s/he is not one of the terrorists. Correspondingly, self-design and selfie making in the offline and online sphere become a necessity for Middle Eastern diaspora to construct an alibi that s/he is not one of the terrorists or a stranger but part of the Western liberal host society. This corresponds with what David Brin (1998) and David Lyon (2007) suggest as “moving toward a transparent society in which information in all spheres is open access.”27 Here, the goal of transparency in self-exposure through self-surveillance is to diminish discrimination against individuals based on their data profiles or other artifacts of the surveillance state. As such Middle Eastern diaspora members being conscious of being monitored participate in surveillance activities with their own choice.

SELFIE ART AS THE SELF-SURVEILLANCE OF BROWN BODY

Middle Eastern artists tend to mention their own stories through their artworks as a means of self-surveillance. The self as “brown” body in artwork combines irregular imaginaries or mainstream contrasting traits together in the form of patchwork for aesthetic contemplation in these art performances of sousveillance. Some diasporic artists can openly claim that their story is a way to resist negative perceptions of their Middle Eastern origin and the brown body’s strangeness while others can simply maintain that this is their story short without any further political aim. Here, the artist’s body part or central part of the artwork becomes a site of identity. This documentation of the brown body in everyday life by means of photography, video, websites, and so forth means exposing it not only to surveillance systems but also to an expanding sphere of media coverage. As such these examples of selfie art constitute a counter body of visual memory against the high volume recordings of brown bodies in “suspicious” acts of endangering the host Western society.

Diasporic artists’ display of the absurdity in their own self-image is a way to oppose their usual imagination in North America. The self in these artworks of selfie-making is insistently objectified and fetishized such that this excess exposes the fiction of literal and allegorical meanings attached to their body-image. Amelia Jones emphasizes that self-body artworks are considered as a strategic self-fetishization and obsessive self-imagining that mimics the processes of stereotyping: “There’s no real self—there—Impossibility of confirming some essential self through the mechanics of simulation;” hence identity is no longer authentic but fully social.28 This game of dialectics in the sense of the use of assumed contrasted traits or signs without promising transcendence becomes the generic artistic tactic in self-image making art.

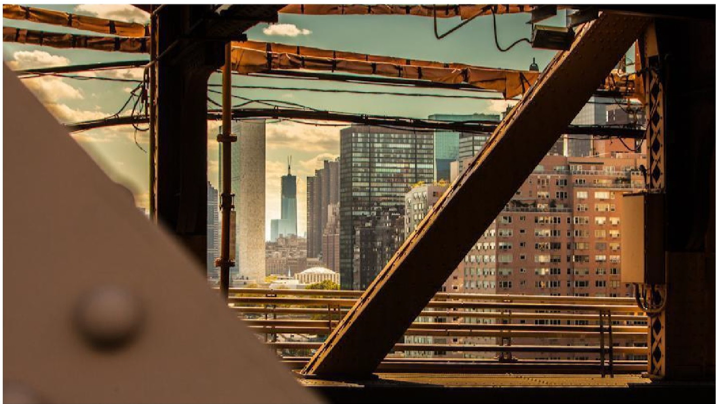

One example of this type of artist is Aymann Ismail, an Egyptian American living in New York. I met with him in May 2013 for an interview in Union Square in New York City. Ismail is a photojournalist in the Animal which is an online website of daily news of New York street life. One title of his videos is “I am Muslim and I shot the World Trade Center” (2012).29 The video shows a high-speed recording of usual daily New York scenery of the World Trade Center from different parts of New York. The video does not show any distraction in the timeline of a New Yorker’s everyday view. Aymann complemented his video with his artistic stance. Just below the video he wrote:

As I was doing this, I was looking over my shoulder and dodging authority figures, out of habit. I am Arab and I look like it. Toting a camera around New York City landmarks made me nervous. I rarely have time to go to the mosque anymore, but over the years, I’ve become somewhat of an ambassador. I’m a typical twenty-three-year-old dude who never leaves his home without headphones. I played bass in an indie hardcore band at Rutgers. I studied art. I listen to hip hop. I find myself having to explain to non-Muslims that no, Islam is not inherently violent. That no, my mother and sister do not wear the scarf because we would chop their heads off otherwise. It is one of the main principles of Islam.

Here, what gives this artwork aesthetic value is the fact that the artist is from the Middle Eastern Diaspora in the United States. He says “I am Arab and I look like it” and he delivers his own experience of doing this artwork to the viewers. His body and accordingly his assumed identity reflect on this process of art-making. The full political dimension of the artwork is brought forward through the artist’s declaration of identity in the sense of self-surveillance. The title of the artwork shocks the viewers since the fact that the title is understood as a confirmation of Muslim crime associated with the World Trade Center attack. Thus, it eventually reveals the scapegoating behavior already present in the spectacle, otherwise the artwork is just a daily record. In that sense, the artistic performance is not the daily record of World Trade Center but the selfsurveillance of being an Arab New Yorker. “I am Muslim and I shot the World Trade Center” is not simply a video but an articulation in relation to others in exchange of identifications. The artwork rearticulates and attempts to undo the connections between the signs of strangeness attached to brown skin and its sense in mainstream visual knowledge. It reclaims the celebration of sameness between the assumed contrasts instead of the difference. He is an American boy with a camera while he looks like and is an Arab originally from Egypt. Hence, self-surveillance delivers a missing imagery of the Middle Eastern diaspora in the mainstream visual regime.

Middle Eastern second-generation diaspora members usually cannot associate themselves with the original homeland while they are persistently associated with their origin in the public sphere, and therefore they struggle for self-articulation in the community while there is no model to refer to them in the media except the images of the discourse of the war on terror and their iconography. 2FIK, the artist, raised in France and living in Quebec, cannot feel belonging through his Arab origin to the Arab Springs:

I thought one moment that I can do something about it but then I realized I was not directly concerned about it. This was pretty shocking. The only thing that links me to the Arab spring is my origin. That is it. In Canada, I live here and I seek another turn. I do not know if the revolution can ever happen in Morocco, but I was not expecting it, it is a dull country politically speaking. The way it functions will not allow an Arab revolution; I don’t think so. At the moment I saw it, I was torn with this excitement and at the same time it inspired me so that I realized how far I am from these countries. How occidentalized I am. It happened. My way of thinking changed a lot and right now I am an occidental dude. I still have the culture everything from Morocco—but I was looking to the Arab spring as an occidental dude.

Negin Farsad, an American-born director of Iranian origin, comedian and stand-up artist, also puts emphasis on the imposed stranger position on her. Farsad mentions how her brown body of Muslim connotation also influences the perception of her stand-up show:

It’s unusual when I talk about sex, dirty sexy package you can accept it with other people but with my package, it is another understanding. . . We are the migrants—stigma women. In the mind of the typical American, Islam is Saudi Arabia and women can’t drive.

Thus, “brown” skinned celebrities who are assumed to be from the Middle East are not numerous in the mainstream media and popular culture. Farsad believes the success of an independent movie, is the only loophole to provide visibility to alternative Middle Eastern subjectivities that the North American mainstream imagination is not accustomed to look at.

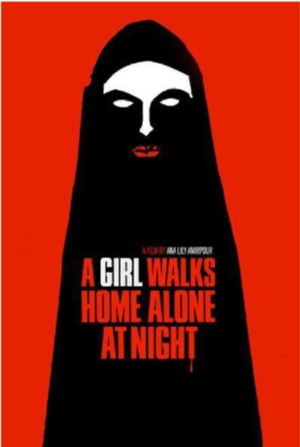

Ana Lily Amirpour is an Iranian-American film director, screenwriter, producer and actor. She is most known for her feature film debut, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014). Watching the movie at its opening night on 23 January 2015 in Toronto,30 I became aware that the theater was full with primarily members of the Middle Eastern diaspora, as well as broader members of the Toronto activist and intellectual community. Friends engaging in Middle Eastern politics or from the Middle Eastern diaspora talked about the movie for some time. It was a real event, long hoped for, to see something “different” about Iran and also about Middle Eastern subjectivities. Thus, a young member of the Middle Eastern diaspora, even one born and raised in North America, cannot see her reflection in the screen. Hence, the movie plays the role of selfie-taking, an act of self-surveillance, for the Middle Eastern diaspora. Amirpour, the director, mentions her connection to Iran:

I did go to Iran, finally, but that’s completely alien to me, It’s weird, because Sheila (artist playing the Girl in chador) and I were talking about how, with this movie, we kind of made our own place that was as Iranian as we are, which is a mash-up of so many things.31

That is why, in Amirpour’s movie, A Girl Walks Alone at Night, Bad City is an Iranian city imagined by the Iranian diaspora rather than Western imagination of an Iranian city. It resists what looks like the “Middle East” or what the Iranian diaspora’s homeland is in the mainstream imagery. Amirpour states that she created her own version of Iran in California to shoot the movie.

The only things that signify that this movie is “Iranian” are: the chador, oil machinery running in the city’s landscape, Arabic letters seen in tattoos and on car plates, a female character seen with a bandage on her nose indicating that she had a nose aesthetic operation (a largely stereotypical operation for Iranian women), and the embroidered bag of the Girl as her suitcase. These are ironic depictions of stereotypical objects of Iranian culture, but in fact, these are only decorative items and are not significant for the flow of the plot in the movie. Indeed, that is why at the end of the screening of A Girl Walks Alone at Night at TIFF, a Canadian Queer identified woman originally from Palestine explained to me why she liked the movie: “Exactly! That is why I liked it. This is not what you expect from an Iranian movie. A vampire in a chador. It is so cool!”

What is in fact “cool” is the artist’s method of “selfie” making used for the aesthetic deconstruction of identity through self-surveillance of the diasporic subjectivity. The film transforms dialectics into a game instead of opposing stereotypes of culture openly. That is why the “Chador” does not prevent the female protagonist from enjoying skateboarding, sex, killing, and being a vampire in the movie. The modern vampire legend designates both a charismatic and sophisticated fictitious hypersexual entity in the undead who feeds on the essence of life. While the presence of vampires is a common belief in many cultures and geographies, the dominant and popular artistic depictions of vampires belong to the Christian legends since the sacred items of Christianity became fetishized in vampire tales: vampires are known to be afraid of the cross, although in the most recent vampires’ stories vampires cannot be harmed by garlic, sunlight, and even crosses, as in the Twilight Series (Stephenie Meyer, 2005–2008). Therefore, a woman in a chador is not supposed to be a vampire, because a religious Muslim woman is assumed to be submissive and oppressed, and hence, not charismatic or sexual at all. Consequently, A Girl Walks Alone Home at Night draws on this very contrast. It deconstructs the popular stereotypes of Middle Eastern victimhood. Thus, the movie juxtaposes stereotypes against each other to dissolve them: the Middle Easterner versus Westerner, the Arab man versus Gay man, the Girl in a chador versus the Girl on a skateboard. That said, contemporary art is not entirely the end of dialectics. The self in these selfie artworks can be objectified and fetishized such that this excess exposes the fiction of literal and allegorical meanings attached to their image through nullifying the contrasts and antagonistic signs.

For instance, 2FIK embraces transvestism, both his gay identity and Muslim Arab origin in his selfie art. He maintains that his performances in the public sphere/social media extends the public imagination of the Middle Eastern diaspora. In the first place, the “gay” identity contradicts the stereotypes of the Arab man with extreme masculinity and violence. 2FIK explains in my interview that his selfie art does not normalize his unconventional personality but it actually makes one exist; and being unexpected is good:

Sometimes I got dressed up, I got this short skirt and veil with my beard but obviously people are going to look at me. Some people laugh, some people want to stab me, I am totally conscious of that—we should not forget that our society is conservative in some sense it is not politically correct but socially correct . . . I am in peace with this.

Another artist, born and raised in Canada, Sabrina Jalees describes herself as a comedian, actor, keynote speaker, and writer based in Brooklyn. Sabrina Jalees also emphasizes her gay identity and how this gay identity fits with her Muslim origin:

When I finish the sentence, I need you guys to gasp, alright? I learnt I was gay (Laughter). Lesbian, was like a weirdo for me—a crazy person, someone that has twenty-five cats (Laughter). That’s a real story. Mine are in the box, backstage. My father is Muslim. Now he expects me to get like ten wives . . . (Applause) I realized eventually was that the more confident and proud I was about this thing that made me different, the more game the audience was to come along with it. And eventually, on the same tour, I was killing using gay material—which is dangerous if there are conservatives here. Tomorrow’s newspaper: ‘Muslim comedian kills using mysterious gay material’ (Laughter). Man (Laughter).32

Here, the contrasting features of the mainstream imagery, as gay identity and Muslim brown body, juxtaposed to reveal the other and to form a surplus. Although the acceptable queer citizen is majorly depicted as a white, gay man, as Johannah May Black33 emphasizes through her case study of the discourse of Pride Week in Toronto, the gay Arab man or gay Pakistani girl do not fit either into the mainstream discourse or the stereotyping of the Middle Eastern diaspora. While the artists’ primary aim is self-surveillance through self-image making as artistic practice, the eventual message is that they are not strangers although they possess a brown body or Middle Eastern origin.

By making the biographies of the surveilled Middle Eastern diaspora publicly visible through selfie art, artists aim to disrupt visual economies of social inclusion and exclusion. Here, diasporic artists do internalize the logic of surveillance and do reproduce in their own art the dominant Middle Eastern connoted stereotypes. For the audience to understand that this selfie is an artwork eventually requires a familiarity with the mainstream portraiture of Middle Eastern imagery and Middle Eastern stereotypes in popular media. However, the artist’s self-body is the terrain where consensual identities become juxtaposed and revealed as an absurdity. Foster states that in contemporary art, there is also a tendency to mimic the “terroristic politics around us” however, “this mimesis is heightened, even exacerbated, to the point of mimicry.34 Here, mimesis connotes a kind of mocking while there is an emphasis on basic universal human traits. Hence, if there is a resistance it is through collaboration with surveillance techniques in these analyzed artworks although sousveillance efforts have limited success at power equalization in comparison.

THE PERCEPTION OF THE SELFIE ART

Although artists’ diasporic identities are reflected in selfie artwork, as long as the self reflects no belonging, it is expected to be “universal” in this account. The ties between the author and the artwork are exposed instead of revealed as secret. Yet, there is neither “host” nor “guest” culture in this understanding: Selfie art is primarily the artist’s individual story. Although it can eventually appeal to a diasporic audience, it is not estimated to represent anybody, culture or community. Farsad mentions in our interview the usual tendency of Middle Eastern diasporic performances or artwork to be particularistic in the sense that they only aim to address to their own diasporic audience. According to Farsad, only reaching “universal appreciation” can allow the Middle Eastern diaspora to escape from stigmatization:

Jews got in the mainstream. They can communicate with people. They are not only crazy fundamentalists. . . Jews but Woody Allen Jews. . . My generation can do that. . . They can communicate with people. . . Jewish comedy is fucking deal. . . It became part of the natural story. . . Hopefully we can do the same. . . Just do comedy. . . Not Iranian but comedy. . .

For instance, Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Alone at Night is a candidate for cult movie status for cinephile spectators. The movie addresses more than the Iranian diaspora, although it still doesn’t attempt to be a mainstream movie. The movie quotes well-known worldwide cult movies; hence the audience needs to acknowledge a specific cultural capital which is inaccessible/accessible to everyone.

While these diasporic artists claim that they deconstruct Islamophobic stereotypes, they can actually be criticized by members of Muslim communities. The primary reason behind this is that the self-image art they are making deconstructs both Islamophobic stereotypes and also the stereotypes of the ideal Muslim for several conservative groups and individuals. I asked 2FIK about comments from other members of the Muslim community. He told of an incident in one of his exhibitions:

One time she asks me, “Could you tell me why you are portraying the veiled woman like that?” I asked her, “Do you think that you are just your veil?” she said, “No” and I said, “Thank you, this is what I was trying to say.”

For instance, the comments on Sabrina Jalees’ Youtube video “Being Half Brown” also attack her statement of being both gay and Muslim. That is why she can be considered as a “fake Muslim” by other Muslims. I also asked Negin Farsad about the comments from members of diasporic Muslim communities on her shows and on the documentary movie The Muslims Are Coming!

We went cities like Binghamton. We don’t have many Muslims in the audience. But we did have 20 percent one time and during the stage, when I was telling jokes many hijabi ladies left. . . I know that they don’t like what I’m doing. . . It’s funny because what I’m trying to make it easier for them, too. I can say I’m Mexican but I say no. . . I am not trying to represent them but just offer another angle from immigrants in America. I’m like, I can’t un-see that. . . Muslim audiences do come and sometimes they hate it and sometimes really appreciate it. . .

Following this context, some of the Muslim or Middle Eastern community seek to preserve their considered distinctive qualifications and customs from what are the assumed generative effects of the Western host culture although they criticize the Islamophobic discourse of the War on Terror. As a matter of fact, the selfie art proposes its own politics through rearrangements of space. While this goal is worthy, as T. J. Demos notes, these kinds of communitybased artworks can risk relying on a notion of community defined as social fusion where convivial agreement drives out the antagonism that is, for others, the very basis of democratic process.35

Yet, the analyzed artworks here reflect the act of self-surveillance and do not represent groups or communities. As such, artists’ efforts tend to carry “selves” around with themselves as designed, recorded, and published as alibi to denounce imposed stereotypes. Thereby these artworks aim to achieve a state of equiveillance in the communal body of visual data to resist hierarchical forms of monitoring and surveillance.

CONCLUSION

My central argument in this paper has been that the self-design became the predominant mark of politico-ethical allegiance and otherization in the visual abundant public sphere. Under the sway of a post September 11 discourse of a high security requirement, visual self-design and its reproduction have become a necessity and hence have fostered new terms of social surveillance and etiquette witnessing upon becoming both the citizen and police. Growing virtual vigilantism has also given rise to selfie art as a means of self-surveillance for Middle Eastern diaspora as a part of extensively monitored segments of Western societies.

The artists of the Middle Eastern diaspora through their selfie art exemplify the growth of sousveillant communities corresponding to the institutional and social surveillance. Here self-surveillance refers to joining the social panopticon rather than being left vulnerable and un-censored. As such, the selfie art designates the claim of the Middle Eastern diaspora to get its own place by its own lens in the visual sphere. As a matter of fact, the analyzed artworks in this article aim to achieve equiveillance in the society for diasporic subjectivities. They are an act of self-transparency, to make artists’ life and personality as open alibi to declare that there exist missing imageries of the Middle Eastern diaspora that resists the mainstream visual regime and its precept of policing. Thereby their art reveals that dominant visual economies do not correspond to the various and diverse subjectivities.

To show the good citizen is no threat, diasporic art does not resist the logic of surveillance but implements vigilant gestures in their own autobiographic artworks. Hence, in comparison to the usual selfie making, selfie art as a genre does explicitly promote an assumed incoherence that does not affirm a reliable or consistent ethnic-cultural-racial stereotyped difference to contemplate on in the artwork. Thus, selfie art as a technique of selfsurveillance becomes a specific type of contemporary art that resists cliches through over-using them to the point that they become mockery. This is not a posture of acquiescence or obedience in the sense that their artworks of selfsurveillance witness their common traits with what is assumed distinguishing and generic of the host Western society and hence disrupt regimes of otherization. For this, selfie art engages in the imagination of universality through the disidentification with what is assumed connected to the Middle East and the claim for human universality instead. But more importantly, selfie art illustrates the act of inversing the roles of monitored and monitoring and of changing the usual play of gaze in the dominant visual realm. That is because self-surveillance means becoming capable of producing one’s own image.

NOTES

Boris Groys, “The Obligation to Self-Design,” in Going Public (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2010), 21–37.↩︎

Steve Mann, “‘Reflectionism’ and ‘Diffusionism’: New Tactics for Deconstructing the Video Surveillance Superhighway,” Leonardo 31, no. 2 (1998): 93–102.↩︎

Steve Mann, Jason Nolan, and Barry Wellman, “Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments,” Surveillance & Society 1, no. 3 (2003): 333.↩︎

Steve Mann, “Sousveillance and Cyborglogs: A 30-Year Empirical Voyage through Ethical, Legal, and Policy Issues,” Presence 14, no. 6 (December 2005): 636.↩︎

Amelia Jones, Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identification and the Visual Arts (New York: Routledge, 2012), 123.↩︎

Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy, trans. Julie Ross (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).↩︎

Roger Clarke, “The Digital Persona and its Application to Data Surveillance” The Information Society 10, no. 2 (June 1994); Dennis Kingsley, “Viewpoint: Keeping a Close Watch—the Rise of Self-Surveillance and the Threat of Digital Exposure,” The Sociological Review 56, no. 3 (2008): 347–57.↩︎

Dennis, “Viewpoint.”↩︎

Michel Foucault, Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan, 2nd ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 1995).↩︎

Jamais Cascio, “Participatory Panopticon,” Perspectives (2007).↩︎

Boris Groys, Boris Groys: Going Public (Berlin; New York: Sternberg Press, 2011).↩︎

Juliane Rebentisch, trans. Daniel Hendrickson, “Forms of Participation in Art,” Qui Parle 23, no. 2 (Spring/ Summer 2015): 29–54.↩︎

Karen-Margrethe Simonsen, “Global Panopticism: On the Eye of Power in Modern Surveillance Society and Post-Orwellian Self-Surveillance and Sousveillance Strategies in Modern Art,” Visualizing Law and Authority: Essays om juridisk cestetik (Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2012): 232–52.↩︎

2FIK, “2FIK OR NOT 2FIK,” accessed 28 June 2015, http://www.2fikornot2fik.com/.↩︎

2FIK, “Identities,” accessed 26 January 2017, http://2fikornot2fik.com/identities/.↩︎

Sarah Ahmed, Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality (London: Routledge, 2000), 30.↩︎

Ibid., 24.↩︎

David Tyrer, “On Tattoos and Other Bodily Inscriptions: Some Reflections on Trauma and Racism,” in Islam and the Politics of Culture in Europe: Memory, Aesthetics, Art, eds. Frank Peter, Sarah Dornhof, and Elena Arigita (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 150.↩︎

Steven Yaccino, Michael Schwirtz, and Marc Santora, “Gunman Kills 6 at Sikh Temple in Wisconsin,” New York Times, 5 August 2013.↩︎

Emily Saul, “Bearded Hipsters Mistaken for ISIS Terrorists,” New York Post, 12 October 2015.↩︎

Mehdi Semati, “Islamophobia, Culture and Race in the Age of Empire” Cultural Studies 24, no. 2 (2010): 256–75.↩︎

The Battle of Algiers, directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, 1967.↩︎

Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1994), 130.↩︎

J.A. Mbembe and Libby Meintjes, “Necropolitics,” Public Culture 15, no. 1 (2003): 37.↩︎

“Orlando Gay Nightclub Shooting: Who Was Omar Mateen?” BBC News, accessed 13 June 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-36513468.↩︎

“Ideology Often a ‘Mask’: Expert,” Metro Canada, accessed 13 June 2016. https://www.pressreader.com/canada/metro-canadatoronto/20160613/281685434123213.↩︎

Jan Fernback, “Sousveillance: Communities of Resistance to the Surveillance Environment,” Telematics and Informatics 30, no. 1 (February 2013): 11–21.↩︎

Tracey Warr and Amelia Jones, The Artist’s Body (London: Phaidon, 2000), 39–42.↩︎

Aymann Ismail, “I Am a Muslim and I Shot the World Trade Center” ANIMAL, accessed 27 January 2017, http://animalnewyork.com/2012/i-am-a-muslim-and-ishot-the-world-trade-center/.↩︎

The movie’s first screening was in Sundance Film Festival in March 2014 at MoMa (New York).↩︎

Robert Ito, “The Shadow in the Chador: Ana Lily Amirpour’s World: ‘A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night,” New York Times, 12 November 2014.↩︎

Sabrina Jalees, “Lesbian Sleepovers: Stand Up Comedy,” online video clip, YouTube, posted 10 April 2014.↩︎

Johannah May Black, “Citizenship Acts: Queer Migrants and the Negotiation of Identity and Belonging at Toronto Pride Week 2009” (MA Thesis, Ryerson University, 2009).↩︎

Hal Foster, Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency (London: Verso), 78.↩︎

T. J. Demos, “Dada’s Event: Paris, 1921,” in Communities of Sense: Rethinking Aesthetics and Politics, ed. Beth Hinderliter, Vered Maimon, Jaleh Mansoor, and Seth McCormick (Durham, NC: Duke University Press), 145.↩︎